An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call the Hands

CALL THE HANDS Issue No. 7 April 2017 From the President Welcome to Call the Hands. Our focus this month is on small vessels that played a large role in Australia's naval history. Similarly, some individuals and small groups who are often overlooked are covered. We look at a young Australian, the little known WW1 naval pilot, Lieutenant R. A. Little who became an ace flying with the Royal Navy Air Service and 11 sailors from HMAS Australia who participated with distinction in the 1918 raid on Zeebrugge. As many stories cannot be covered in detail I hope you find the links and recommended ‘further reading’ of value. Likewise, the list of items included in ‘this month in history’ is larger. This may wet appetites to search our website for relevant stories of interest. I would like to acknowledge the recent gift of a collection of books and DVDs to the Society's library by Mrs Jocelyn Looslie. Sadly, her husband, RADM Robert Geoffrey Looslie, CBE, RAN passed away on 5 September 2016 at age 90. His long and distinguished career of 41 years commencing in 1940 included four sea commands. One of these was the guided missile destroyer HMAS Brisbane (1971–1972). During this period Brisbane conducted its second Vietnam deployment. David Michael From the Editor Occasional Paper 6 published in March 2017 listed RAN ships lost over a century. Whilst feedback was positive we acknowledge subscribers and members who pointed out omissions which included; HMA ships Tarakan1, Woomera and Arrow. The tragic circumstances of their loss and the lives of their sailors underscores the inherent risks our men and women face daily at sea in peace and war. -

The Vietnam War an Australian Perspective

THE VIETNAM WAR AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE [Compiled from records and historical articles by R Freshfield] Introduction What is referred to as the Vietnam War began for the US in the early 1950s when it deployed military advisors to support South Vietnam forces. Australian advisors joined the war in 1962. South Korea, New Zealand, The Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand also sent troops. The war ended for Australian forces on 11 January 1973, in a proclamation by Governor General Sir Paul Hasluck. 12 days before the Paris Peace Accord was signed, although it was another 2 years later in May 1975, that North Vietnam troops overran Saigon, (Now Ho Chi Minh City), and declared victory. But this was only the most recent chapter of an era spanning many decades, indeed centuries, of conflict in the region now known as Vietnam. This story begins during the Second World War when the Japanese invaded Vietnam, then a colony of France. 1. French Indochina – Vietnam Prior to WW2, Vietnam was part of the colony of French Indochina that included Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Vietnam was divided into the 3 governances of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. (See Map1). In 1940, the Japanese military invaded Vietnam and took control from the Vichy-French government stationing some 30,000 troops securing ports and airfields. Vietnam became one of the main staging areas for Japanese military operations in South East Asia for the next five years. During WW2 a movement for a national liberation of Vietnam from both the French and the Japanese developed in amongst Vietnamese exiles in southern China. -

The British Commonwealth and Allied Naval Forces' Operation with the Anti

THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AND ALLIED NAVAL FORCES’ OPERATION WITH THE ANTI-COMMUNIST GUERRILLAS IN THE KOREAN WAR: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE OPERATION ON THE WEST COAST By INSEUNG KIM A dissertation submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the British Commonwealth and Allied Naval forces operation on the west coast during the final two and a half years of the Korean War, particularly focused on their co- operation with the anti-Communist guerrillas. The purpose of this study is to present a more realistic picture of the United Nations (UN) naval forces operation in the west, which has been largely neglected, by analysing their activities in relation to the large number of irregular forces. This thesis shows that, even though it was often difficult and frustrating, working with the irregular groups was both strategically and operationally essential to the conduct of the war, and this naval-guerrilla relationship was of major importance during the latter part of the naval campaign. -

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

RAN Ships Lost

CALL THE HANDS OCCASIONAL PAPER 6 Issue No. 6 March 2017 Royal Australian Navy Ships Honour Roll Given the 75th anniversary commemoration events taking place around Australia and overseas in 2017 to honour ships lost in the RAN’s darkest year, 1942 it is timely to reproduce the full list of Royal Australian Navy vessels lost since 1914. The table below was prepared by the Directorate of Strategic and Historical Studies in the RAN’s Sea Power Centre, Canberra lists 31 vessels lost along with a total of 1,736 lives. Vessel (* Denotes Date sunk Casualties Location Comments NAP/CPB ship taken up (Ships lost from trade. Only with ships appearing casualties on the Navy Lists highlighted) as commissioned vessels are included.) HMA Submarine 14-Sep-14 35 Vicinity of Disappeared following a patrol near AE1 Blanche Bay, Cape Gazelle, New Guinea. Thought New Guinea to have struck a coral reef near the mouth of Blanche Bay while submerged. HMA Submarine 30-Apr-15 0 Sea of Scuttled after action against Turkish AE2 Marmara, torpedo boat. All crew became POWs, Turkey four died in captivity. Wreck located in June 1998. HMAS Goorangai* 20-Nov-40 24 Port Phillip Collided with MV Duntroon. No Bay survivors. HMAS Waterhen 30-Jun-41 0 Off Sollum, Damaged by German aircraft 29 June Egypt 1941. Sank early the next morning. HMAS Sydney (II) 19-Nov-41 645 207 km from Sunk with all hands following action Steep Point against HSK Kormoran. Located 16- WA, Indian Mar-08. Ocean HMAS Parramatta 27-Nov-41 138 Approximately Sunk by German submarine. -

177Th 2013 Australia Day Regatta

Endorsed by Proudly sponsored by 177TH AUSTRALIA DAY REGATTA 2013 At Commonwealth Private we understand that our business relies on your continued success. This means we will find the solution that works for you, regardless of whether it includes a product of ours or not. Tailored advice combined with expert analysis, unique insights and the unmatched resources of Australia’s largest financial institution. A refreshing approach that can take you further, and together, further still. Winner of the Outstanding Institution Award for clients with $1-$10 million, four years in a row. commonwealthprivate.com.au Things to know before you can: This advertisement has been prepared by Commonwealth Private Limited ABN 30 125 238 039 AFSL 314018 a wholly owned by non-guaranteed subsidiary of Commonwealth Bank of Australia ABN 48 123 123 124, AFSL and Australian Credit Licence 234945. The services described are provided by teams consisting of Private Bankers who are representatives of Commonwealth Bank of Australia, and Private Wealth Managers who are representatives of Commonwealth Private Ltd. FROM THE PRESIDENT I again acknowledge the Armed Services for their role in supporting our Australia Day is an occasion on which all Australians can nation. Their participation celebrate our sense of nationhood. is important to our We honour the first Australians and pay respects to the Australia Day celebration Gadigal and Cammeragil people, recognising them as having and I particularly thank been fine custodians of Sydney Harbour. We acknowledge the Royal Australian the Europeans who established our modern Australia, those Navy which provides our early settlers who showed great fortitude and commitment flagship for the Regatta. -

FRIDAY 26Th October

Sir Ernest Shackleton FRIDAY 26th October Born close to the village of Kilkea, between Castledermot and Athy, in the south of County ‘A Master Class with a Master Sculptor’ Kildare in 1874, Ernest Shackleton is renowned 11.00am Sculptor Mark Richards who created Athy’s acclaimed Shackleton for his courage, his commitment to the welfare statue will conduct a workshop with Leaving Certificate Art of his comrades, and his immense contribution students from Athy Community College and Ardscoil Na Trionóide. to exploration and geographical discovery. The Shackleton family first came to south Kildare in the Official Opening & Exhibition Launch early years of the eighteenth century. Ernest’s Quaker 7.30pm Performed by Her Excellency, Ambassador Else Berit Eikeland, the forefather, Abraham Shackleton, established a multi- denominational school in the village of Ballitore. Norwegian Ambassador to Ireland. This school was to educate such notable figures as Napper Tandy, Edmund Burke, Cardinal Paul Cullen Book Launch Athy Heritage Centre - Museum and Shackleton’s great aunt, the Quaker writer, 8.00pm In association with UCL publishers, the Mary Leadbeater. Apart from their involvement Shackleton Autumn School is pleased to in education, the extended family was also deeply involved in the business and farming life of south welcome back to Athy Shane McCorristine Kildare. for the launch of his latest work The Spectral Having gone to sea as a teenager, Shackleton joined Arctic: A History of Ghosts and Dreams in Polar Captain Scott’s Discovery expedition (1901 – 1904) Exploration. Through new readings of archival and, in time, was to lead three of his own expeditions documents, exploration narratives and fictional to the Antarctic. -

The Most Vitriolic Parliament

THE MOST VITRIOLIC PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE OF THE VITRIOLIC NATURE OF THE 43 RD PARLIAMENT AND POTENTIAL CAUSES Nicolas Adams, 321 382 For Master of Arts (Research), June 2016 The University of Melbourne, School of Social and Political Sciences Supervisors: Prof. John Murphy, Dr. Scott Brenton i Abstract It has been suggested that the period of the Gillard government was the most vitriolic in recent political history. This impression has been formed by many commentators and actors, however very little quantitative data exists which either confirms or disproves this theory. Utilising an analysis of standing orders within the House of Representatives it was found that a relatively fair case can be made that the 43rd parliament was more vitriolic than any in the preceding two decades. This period in the data, however, was trumped by the first year of the Abbott government. Along with this conclusion the data showed that the cause of the vitriol during this period could not be narrowed to one specific driver. It can be seen that issues such as the minority government, style of opposition, gender and even to a certain extent the speakership would have all contributed to any mutation of the tone of debate. ii Declaration I declare that this thesis contains only my original work towards my Masters of Arts (Research) except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text to other material used. Equally this thesis is fewer than the maximum word limit as approved by the Research Higher Degrees Committee. iii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge my two supervisors, Prof. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

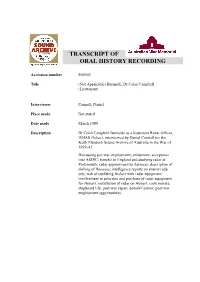

Transcript of Oral History Recording

TRANSCRIPT OF ORAL HISTORY RECORDING Accession number S00543 Title (Not Applicable) Burnside, Dr Colin Campbell (Lieutenant) Interviewer Connell, Daniel Place made Not stated Date made March 1989 Description Dr Colin Campbell Burnside as a lieutenant Radar Officer, HMAS Hobart, interviewed by Daniel Connell for the Keith Murdoch Sound Archive of Australia in the War of 1939–45 Discussing pre-war employment; enlistment; acceptance into ASDIC; transfer to England and studying radar at Portsmouth; radar appointment to Adelaide; description of sinking of Rameses; intelligence reports on enemy radar sets; task of outfitting Hobart with radar equipment; involvement in selection and purchase of radar equipment for Hobart; installation of radar on Hobart; crew morale; shipboard life; post-war Japan; demobilisation; post-war employment opportunities. COLIN CAMPBELL Page 2 of 34 Disclaimer The Australian War Memorial is not responsible either for the accuracy of matters discussed or opinions expressed by speakers, which are for the reader to judge. Transcript methodology Please note that the printed word can never fully convey all the meaning of speech, and may lead to misinterpretation. Readers concerned with the expressive elements of speech should refer to the audio record. It is strongly recommended that readers listen to the sound recording whilst reading the transcript, at least in part, or for critical sections. Readers of this transcript of interview should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal conversational style that is inherent in oral records. Unless indicated, the names of places and people are as spoken, regardless of whether this is formally correct or not – e.g. -

The Anglo-Omani Society Review 2016

New Generation Group Edition Across the Rub al Khali …IN THE STEPS OF BERTRAM THOMAS AND BIN KALUT William&Son_2016_Layout 1 19/09/2016 16:42 Page 1 003-005 - Contents&Officers_Layout 1 19/09/2016 11:50 Page 3 JOURNAL NO. 80 COVER PHOTO: In the Footsteps of Bertram Thomas Photo Credit: John Smith CONTENTS 6 CHAIRMAN’S OVERVIEW 51 OMAN IN THE YEARS OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR 8 THE 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY 53 NEW GENERATION GROUP INTRODUCTION A HISTORY OF NGG EVENTS NGG IN OMAN NGG DELEGATIONS 2013-15 NGG DELEGATION 2016 SOCIAL MEDIA OMANI STUDENTS UK INTERNSHIP PROGRAMME NGG’S PARTNER ORGANISATIONS MOHAMMED HASSAN PHOTOGRAPHY 14 IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF BERTRAM THOMAS 20 THE ROYAL CAVALRY OF OMAN 88 EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES 93 THE ‘ABC’ OF OMAN INSECTS 96 ANGLO-OMANI LUNCHEON 22 UNDER THE MICROSCOPE: A CLOSER LOOK AT OMANI SILVER 98 THE SOCIETY’S GRANT SCHEME 26 THE ESMERALDA SHIPWRECK OFF 100 ARABIC LANGUAGE SCHEME AL HALLANIYAH ISLAND 105 AOS LECTURE PROGRAMME 29 MUSCAT “THE ANCHORAGE” 106 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY 34 OMAN THROUGH THE EYES OF GAP YEAR SCHEME SUE O’CONNELL 108 SUPPORT FOR YOUNG OMANI SCHOLARS 36 BAT OASIS HERITAGE PROJECT 110 LETTER TO THE EDITOR 40 OMAN THROUGH THE EYES OF PETER BRISLEY 112 BOOK REVIEWS 42 THE BRITISH EMBASSY: RECOLLECTIONS OF THE FIRST AMBASSADRESS 114 MEET THE SOCIETY STAFF 46 ROYAL GUESTS AT A RECEPTION 115 WHERE WAS THIS PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN? 3 003-005 - Contents&Officers_Layout 1 19/09/2016 11:50 Page 4 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY Society Address 34, Sackville Street, London W1S 3ED +44 (0)20 7851 7439 Patron www.angloomanisociety.com HM Sultan Qaboos bin Said Advertising Christine Heslop 18 Queen’s Road, Salisbury, Wilts. -

Civil War Era Correspondence Collection

Civil War Era Correspondence Collection Processed by Curtis White – Fall 1994 Reprocessed by Rachel Thompson – Fall 2010 Table of Contents Collection Information Volume of Collection: Two Boxes Collection Dates: Restrictions: Reproduction Rights: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History Location: Archives Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Biographical Sketches Anonymous: This folder consists of one photocopy of a letter from an unknown soldier to “Sallie” about preparations for the Battle of Allegheny Mountain, Virginia (now West Virginia). Anonymous [J.A.R?]: This folder contains the original and enlarged and darkened copies of a letter describing to the author’s sister his sister the hardships of marching long distances, weather, and sickness. Reuben M. Benjamin was born in June 1833 in New York. He married Laura W. Woodman in 1857. By 1860, they were residents of Bloomington, IL. Benjamin was an attorney and was active in the 1869 Illinois Constitutional Convention. Later, he became an attorney in the lead Granger case of Munn vs. the People which granted the states the right to regulate warehouse and railroad charges. In 1873, he was elected judge in McLean County and helped form the Illinois Wesleyan University law school. His file consists of a transcript of a letter to his wife written from La Grange, TN, dated January 21, 1865. He may have been part of a supply train regiment bringing food and other necessities to Union troops in Memphis, TN. This letter mentions troop movements. Due to poor health, Benjamin served only a few months.