Division on the Western Front, 1916-1918 By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War I Casualty Biographies

St Martins-Milford World War I Casualty Biographies This memorial plaque to WW1 is in St Martin’s Church, Milford. There over a 100 listed names due to the fact that St Martin’s church had one of the largest congregations at that time. The names have been listed as they are on the memorial but some of the dates on the memorial are not correct. Sapper Edward John Ezard B Coy, Signal Corps, Royal Engineers- Son of Mr. and Mrs. J Ezard of Manchester- Husband of Priscilla Ezard, 32, Newton Cottages, The Friary, Salisbury- Father of 1 and 5 year old- Born in Lancashire in 1883- Died in hospital 24th August 1914 after being crushed by a lorry. Buried in Bavay Communal Cemetery, France (12 graves) South Part. Private George Hawkins 1st Battalion Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry- Son of George and Caroline Hawkins, 21 Trinity Street, Salisbury- Born in 1887 in Shrewton- He was part of the famous Mon’s retreat- His body was never found- Died on 21st October 1914. (818 died on that day). Commemorated on Le Touret Memorial, France. Panel 19. Private Reginald William Liversidge 1st Dorsetshire Regiment- Son of George and Ellen Liversidge of 55, Culver Street, Salisbury- Born in 1892 in Salisbury- He was killed during the La Bassee/Armentieres battles- His body was never found- Died on 22nd October 1914 Commemorated on Le Touret Memorial, France. Panel 22. Corporal Thomas James Gascoigne Shoeing Smith, 70th Battery Royal Field Artillery- Husband of Edith Ellen Gascoigne, 54 Barnard Street, Salisbury- Born in Croydon in 1887-Died on wounds on 30th September 1914. -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

The First World War Centenary Sale | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 1 October 2014 21999

ALE S ENARY ENARY T WORLD WAR CEN WORLD WAR T Wednesday 1 October 2014 Wednesday Knightsbridge, London THE FIRS THE FIRST WORLD WAR CENTENARY SALE | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 1 October 2014 21999 THE FIRST WORLD WAR CENTENARY SALE Wednesday 1 October 2014 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London BONHAMS ENQUIRIES SALE NUMBER IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street 21999 The United States Government Knightsbridge Books, Manuscripts, has banned the import of ivory London SW7 1HH Photographs and Ephemera CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing www.bonhams.com Matthew Haley £20 ivory are indicated by the symbol +44 (0)20 7393 3817 Ф printed beside the lot number VIEWING [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder in this catalogue. Sunday 28 September information including after-sale 11am to 3pm Medals collection and shipment. Monday 29 September John Millensted 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0)20 7393 3914 Please see back of catalogue Tuesday 30 September [email protected] for important notice to bidders 9am to 4.30pm Wednesday 1 October Militaria ILLUSTRATIONS 9am to 11am David Williams Front cover: Lot 105 +44 (0)20 7393 3807 Inside front cover: Lot 48 BIDS [email protected] Inside back cover: Lot 128 +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Back cover: Lot 89 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Pictures and Prints To bid via the internet Thomas Podd please visit www.bonhams.com +44 (0)20 7393 3988 [email protected] New bidders must also provide proof of identity when submitting Collectors bids. Failure to do this may result Lionel Willis in your bids not being processed. -

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

THE WESTERN FRONT World War

INTRODUCTORY NOTES movement in their efforts to win. Also there is the opportunity to examine other aspects of life on the By 1907 Europe was divided into two armed camps Western Front which affected the life of the ordinary that involved all the major European powers, the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente. While the alliances soldier, such as living conditions, food, medical problems, army routine, discipline and humour. were meant to increase the security of each country, instead they ensured that a war that involved any of these powers would probably involve all of them. WAR PLANS Between the Anglo-French Cordiale of 1904 and the outbreak of war in 1914, there were a number of There had not been major war in Europe since 1870. Teacher's Notes crises in Morocco and the Balkans, any of which Much had changed since then. Population growth meant could have sparked a war. more men were available to be conscripted, industrial advancements meant armies could be equipped with It was the assassination of the Austrian heir to the more devastating weapons, railways meant armies could throne, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, be more easily moved and supplied. Every army had a 1914, that finally ignited the European powder keg. general staff, whose job it was to ensure their nations THE WESTERN Following the declaration of war on Serbia by Austria- army was properly equipped and organised for war and to Hungary on July 28, 1914, the Russian Government prepare plans to cover the most likely scenario. ordered its army to mobilise. -

Oce20801 WW1 Battle of the Somme Fact Sheet A4.Qxp

LOCAL STUDIES CENTRE FACT SHEET NUMBER 27 Battle of the Somme The Battle of the Somme, also known as the Somme Offensive, was fought by the armies of the British and French Empires against the German Empire. It occurred between 1 July 1916 and November 1916 in France and was one of the largest and bloodiest battles of the First World War in which more than 1,000,000 men were wounded or killed. By the end of the first day, 20,000 men had been killed and another 40,000 injured. The first British tank to be used in warfare entered the battlefields of the Somme in September 1916. When the Battle of the Somme ended in November 1916 the Allies had managed to advance only five - seven miles in four months at the cost of over 420,000 British casualties, 195,000 French and 650,000 Germans. Over 500 Sunderland born soldiers were killed throughout this duration, over 170 Wearside soldiers on the first day of the battle alone. There are over 250 military cemeteries and memorials on the Somme battlefields for the many thousands of casualties who fell during this offensive. Pozieres British Cemetery 1914 - 1918 Sunderland and the Somme Sunderland affiliated units deployed in the Battle of the Somme included Durham Light Infantry (7th and 20th), 160th Brigade Royal Field Artillery and Northumberland Hussars to name but a few. These units were recruited in Sunderland and the Territorial Force units were based at the Drill Hall, which was situated near Green Terrace and the Empire Theatre in Durham Light Infantry 20th Division Sunderland city centre. -

Canada and the BATTLE of VIMY RIDGE 9-12 April 1917 Bataille De Vimy-E.Qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 4

BRERETON GREENHOUS STEPHEN J. HARRIS JEAN MARTIN Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 2 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 1 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 3 BRERETON GREENHOUS STEPHEN J. HARRIS JEAN MARTIN Canada and the BATTLE OF VIMY RIDGE 9-12 April 1917 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 4 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Greenhous, Brereton, 1929- Stephen J. Harris, 1948- Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917 Issued also in French under title: Le Canada et la Bataille de Vimy 9-12 avril 1917. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-660-16883-9 DSS cat. no. D2-90/1992E-1 2nd ed. 2007 1.Vimy Ridge, Battle of, 1917. 2.World War, 1914-1918 — Campaigns — France. 3. Canada. Canadian Army — History — World War, 1914-1918. 4.World War, 1914-1918 — Canada. I. Harris, Stephen John. II. Canada. Dept. of National Defence. Directorate of History. III. Title. IV.Title: Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917. D545.V5G73 1997 940.4’31 C97-980068-4 Cet ouvrage a été publié simultanément en français sous le titre de : Le Canada et la Bataille de Vimy, 9-12 avril 1917 ISBN 0-660-93654-2 Project Coordinator: Serge Bernier Reproduced by Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence Headquarters Jacket: Drawing by Stéphane Geoffrion from a painting by Kenneth Forbes, 1892-1980 Canadian Artillery in Action Original Design and Production Art Global 384 Laurier Ave.West Montréal, Québec Canada H2V 2K7 Printed and bound in Canada All rights reserved. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

The Durham Light Infantry and the Somme 1916

The Durham Light Infantry and The Somme 1916 by John Bilcliffe edited and amended in 2016 by Peter Nelson and Steve Shannon Part 4 The Casualties. Killed in Action, Died of Wounds and Died of Disease. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License You can download this work and share it with others as long as it is credited, but you can’t change it in any way or use it commercially © John Bilcliffe. Email [email protected] Part 4 Contents. 4.1: Analysis of casualties sustained by The Durham Light Infantry on the Somme in 1916. 4.2: Officers who were killed or died of wounds on the Somme 1916. 4.3: DLI Somme casualties by Battalion. Note: The drawing on the front page of British infantrymen attacking towards La Boisselle on 1 July 1916 is from Reverend James Birch's war diary. DCRO: D/DLI 7/63/2, p.149. About the Cemetery Codes used in Part 4 The author researched and wrote this book in the 1990s. It was designed to be published in print although, sadly, this was not achieved during his lifetime. Throughout the text, John Bilcliffe used a set of alpha-numeric codes to abbreviate cemetery names. In Part 4 each soldier’s name is followed by a Cemetery Code and, where known, the Grave Reference, as identified by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Here are two examples of the codes and what they represent: T2 Thiepval Memorial A5 VII.B.22 Adanac Military Cemetery, Miraumont: Section VII, Row B, Grave no. -

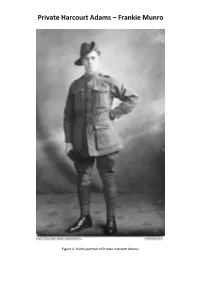

Private Harcourt Adams – Frankie Munro

Private Harcourt Adams – Frankie Munro Figure 1: Studio portrait of Private Harcourt Adams. These are the stories of two brave Tasmanian men. The first of which, my friend’s ancestor, a sailor from Swansea, killed at Pozières in 1916. The second, a lost relative of mine that I discovered through the Frank MacDonald Memorial Prize, also killed at Pozières in 1916. Harcourt (Duke) Adams was born in Swansea on the 8 August 1890 to parents Frederick and Alice Adams. Prior to his enlistment, he was a fireman on board a steamship owned by the Mt. Lyell Co. When his ship was in port in Hobart, he lived with his mother and younger sister, Ivy. His four other sisters, Minnie, Violet, Lilly and Ruby had married and lived elsewhere, and his father tragically passed away several years before the war, so Harcourt was providing the only income for them when he enlisted. Harcourt enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on the 11 June 1915, aged 24. He was given the service number 2496 and assigned to the 15th Battalion, 7th Reinforcements. Figure 2: 15th Battalion AIF colour patch. On the 17 July 1915, Harcourt embarked from Melbourne on board the HMAT Orsova A67. Several photographs were taken of the ship as it left Port Melbourne, the soldiers can be seen lining the deck, bidding farewell to the crowd, some even climbed the rigging. There is the possibility that one of those men was Harcourt. Figure 3: HMAT Orsova A67 leaving Port Melbourne, 17.07.1915. Figure 4: A closeup shot of the Orsova showing the Australian soldiers on board, 17.07.1915. -

The Combat Effectiveness of Australian and American Infantry Battalions in Papua in 1942-1943 Bryce Michael Fraser University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 The combat effectiveness of Australian and American infantry battalions in Papua in 1942-1943 Bryce Michael Fraser University of Wollongong Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Faculty of Arts School of History and Politics The combat effectiveness of Australian and American infantry battalions in Papua in 1942-1943 Bryce Michael Fraser, BA. This thesis is presented as the requirement for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong March 2013 CERTIFICATION I, Bryce Michael Fraser, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. B M Fraser 25 March 2013 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES iv ABBREVIATIONS vii ABSTRACT viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS x Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Theory and methodology 13 Chapter 2: The campaign and the armies in Papua 53 Chapter 3: Review of literature and sources 75 Chapter 4 : The combat readiness of the battalions in the 14th Brigade 99 Chapter 5: Reinterpreting the site and the narrative of the battle of Ioribaiwa 135 Chapter 6: Ioribaiwa battle analysis 185 Chapter 7: Introduction to the Sanananda road 211 Chapter 8: American and Australian infantry battalions in attacks at the South West Sector on the Sanananda road 249 Chapter 9: Australian Militia and AIF battalions in the attacks at the South West Sector on the Sanananda road.