Tracing Traffic, Place, and Power in Canada's Capital City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Manager, Transportation Services, Vivi Chi, Director, Services Department Transportation Planning

M E M O / N O T E D E S E R V I C E Information previously distributed / Information distribué auparavant TO: Transportation Committee DESTINATAIRE : Comité des transports FROM: John Manconi, Contact: Phil Landry, Director, Traffic General Manager, Transportation Services, Vivi Chi, Director, Services Department Transportation Planning EXPÉDITEUR : John Manconi, Personne ressource : Philippe Landry, Directeur général, Direction générale Gestionnaire, Services de la circulation, des transports Vivi Chi, Planification des transports, DATE: February 27, 2018 27 février 2018 FILE NUMBER: ACS2018-TSD-GEN-0001 SUBJECT: Report on the use of Delegated Authority during 2017 by the Transportation Services Department as set out in Schedule “G” Transportation Services of By-law 2016-369 OBJET : Rapport sur l’utilisation de Délégation de pouvoirs en 2017 par la direction générale des Services des Transports, comme il est indiqué à l’annexe G Services des Transports, du régulant 2016-369 PURPOSE The purpose of this memorandum is to report to the Transportation Committee on the use of delegated authority for 2017 under Schedule ‘G’ – Transportation Services of By- Law 2016-369. 1 BACKGOUND By-law 2016-369 is “a by-law of the City of Ottawa respecting the delegation of authority to various officers of the City”. The By-law was enacted by Council on November 9, 2016 and is meant to repeal By-law No. 2014-435. This By-Law provides delegated authority to officers within the Transportation Services Department to perform various operational activities, and requires that use of delegated authority be reported to the appropriate standing committee at least once per year. -

Minto Commercial Properties Inc. Illustrative Purposes

Morgan’s Grant (Kanata) | Retail Plaza (73,000 sq. ft.) OTTAWA OVERVIEW MAP LOCATION MAP AERIAL MAP SITE MAP DUNROBIN ROAD FERRY ROAD 2001 Population and Households TORBOLTON RIDGE ROAD Zone Population Households GALETTA SIDE ROAD FITZROY PTA 6,909 2,165 HARBOUR CONSTANCE BAY STA1 14,544 5,015 QUEBEC STA2 12,790 4,470 CARP ROAD STA Total 27,334 9,485 WOODKILTON ROAD TA Total 34,243 11,650 VANCE SIDE ROAD 5 LINE ROAD Source: Statistics Canada 2001 Census Population Projections (TA Total) Year Population LOGGERS WAY JOHN SHAW ROAD DUNROBIN TORWOOD DRIVE 2005 41,200 MOHR ROAD 2010 50,500 DUNROBIN ROAD STA 2 2 LINE ROAD KERWIN ROAD KERWIN 2015 58,200 KINBURN SIDEROAD DIAMONDVIEW ROAD KINBURN PTA RIDDELL DRIVE MARCH VALLEY RD. DONALD B. MUNRO DRIVE 17 MARCHURST ROAD THOMAS A. DOLAN PARKWAY FARMVIEW ROAD MARCH ROAD OTTAWA RIVER 2 LINE ROAD UPPER DWYER HILL ROAD KLONDIKE ROAD CARP MARCH ROAD LEGGET DRIVESANDHILL ROAD THOMAS ARGUE ROAD TERRY FOX DRIVE SUBJECT SITE GOULBOURNFORCEDRD. SHANNA ROAD HINES ROAD CARLING AVENUEOTTAWA DIAMONDVIEW ROAD OLD CARPKANATA ROAD TERON ROAD CARP ROAD MARSHWOOD ROAD 417 417 HUNTMARSTA DRIVE 1 CONCESSION ROAD 12 OLD CREEK DRIVE TIMM ROAD CAMPEAU DRIVE ROBERTSON ROAD PANMURE ROAD MARCH ROAD PALLADIUM DRIVE HAZELDEAN ROAD RICHARDSON SIDE ROAD MAPLE GROVE ROAD 7 STITTSVILLE For discussion and/or Minto Commercial Properties Inc. illustrative purposes. Subject to change without notice 613-786-3000 minto.com Morgan’s Grant (Kanata) | Retail Plaza (73,000 sq. ft.) OTTAWA OVERVIEW MAP LOCATION MAP AERIAL MAP SITE MAP Future Residential Existing Future Residential Residential MARCH ROAD KLONDIKE ROAD FLAMBOROUGH WAY MERSEY DRIVE MORGAN’S GRANT For discussion and/or Minto Commercial Properties Inc. -

Environmental Assessment for a New Landfill Footprint at the West Carleton Environmental Centre

Waste Management of Canada Corporation Environmental Assessment for a New Landfill Footprint at the West Carleton Environmental Centre SOCIO-ECONOMIC EXISTING CONDITIONS REPORT Prepared by: AECOM Canada Ltd. 300 – 300 Town Centre Boulevard 905 477 8400 tel Markham, ON, Canada L3R 5Z6 905 477 1456 fax www.aecom.com Project Number: 60191228 Date: October, 2011 Socio-Economic Existing Conditions Report West Carleton Environmental Centre Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Documentation ..................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Socio-Economic Study Team ............................................................................... 2 2. Landfill Footprint Study Areas .......................................................................... 3 3. Methodology ....................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Local Residential and Recreational Resources .................................................... 4 3.1.1 Available Secondary Source Information Collection and Review .............. 4 3.1.2 Process Undertaken ................................................................................. 5 3.2 Visual ................................................................................................................... 6 3.2.1 Approach ................................................................................................. -

Project Synopsis

Final Draft Road Network Development Report Submitted to the City of Ottawa by IBI Group September 2013 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Approach ............................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Report Structure .................................................................................................. 3 2. Background Information ...................................................................... 4 2.1 The TRANS Screenline System ......................................................................... 4 2.2 The TRANS Forecasting Model ......................................................................... 4 2.3 The 2008 Transportation Master Plan ............................................................... 7 2.4 Progress Since 2008 ........................................................................................... 9 Community Design Plans and Other Studies ................................................................. 9 Environmental Assessments ........................................................................................ 10 Approvals and Construction .......................................................................................... 10 3. Needs and Opportunities .................................................................. -

Carling Avenue Asking Rent: $16.00 Psf

CARLING 1081AVENUE [ OFFICE SPACE FOR LEASE ] Jessica Whiting Sarah Al-Hakkak Sales Representative Sales Representative +1 613 683 2208 +1 613 683 2212 [email protected] [email protected] CARLING 1081AVENUE [ SPECIFICATIONS ] ADDRESS: 1081 CARLING AVENUE ASKING RENT: $16.00 PSF LOCATION: CIVIC HOSPITAL ADDITIONAL RENT: $16.85 PSF SITE AREA: 322 SF - 6,917 SF [ HIGHLIGHTS ] 1081 Carling is a professionally managed □ Aggressive incentive: Any new tenant to sign a lease by medical building located at the corner December 31, 2018 will receive 6 months net free rent on a 5+ year deal of Parkdale and Carling Avenue. This well positioned building has a nice sense of □ Turnkey options available community with a variety of prominent □ New improvements and upgrades to the common areas medical tenants. Located in close proximity to the Ottawa Civic Hospital □ On-site parking and rapid transit at doorstep and the Royal Ottawa Mental Health □ Multiple suites available Centre, on-site amenities include a café □ Available immediately and a pharmacy. CARLING 1081AVENUE [ AVAILABLE SPACE ] SUITE SIZE (SF) B2 812 202 662 207 4,274 304 322 308 4,372 403 678 409 673 502 674 504 671 600 6,917 707A/707B 4,361 805 1,070 CARLING 1081AVENUE [ FLOOR PLAN ] SUITE 207 - 4,274 SF CARLING 1081AVENUE [ FLOOR PLAN ] SUITE 409 - 673 SF CARLING 1081AVENUE [ FLOOR PLAN ] SUITE 504 - 671 SF CARLING 1081AVENUE [ FLOOR PLAN ] 6TH FLOOR - 6,917 SF [ AMENITIES MAP ] 1 Ottawa Civic Hospital Royal Ottawa Mental Health 2 LAURIER STREET Centre 3 Experimental -

Community Amenities Spreadsheet

Facility Name Address Amenities Provided LIBRARY 1 Ottawa Public Library - Main Branch 120 Metcalfe Street Meeting rooms available 2 Museum of Nature 240 McLeod St SCHOOLS / EDUCATION enrolement capacity 1 Albert Street Secondary Alternative 440 Albert St administrative program ‐ no students 2 Centennial Public School 376 Gloucester St Play structure, therapeutic pool, 195 321 3 Elgin Street Public School 310 Elgin St 2 play structures, basketball net, baseball diamond, and outdoor skating rink. 251 242 4 Glashan Public School 28 Arlington Ave 2 large gyms 344 386 5 Lisgar Collegiate Institute 29 Lisgar St 807 1089 6 St. Patrick Adult H.S. 290 Nepean St 7 Cambridge Street Community P.S. 250 Cambridge St Soccer field / baseball, volleyball, Play structure 127 311 8 Richard Pfaff Secondary Alternative 160 Percy Street See McNabb Recreation Centre below 270 340 First Place Alternate Programe 160 Percy Street See McNabb Recreation Centre below included in Richard Pfaff 9 Museum of Nature 240 McLeod St 10 National Arts Centre 53 Elgin Street HEALTH CENTRES & PHYSICIANS 1 Morissette 100 Argyle Ave 2 Moore 116 Lisgar St 3 Ballyÿ 219 Laurier Ave West O'Connor Health Group 4 Akcakir 267 O'Connor St Griffiths 267 O'Connor St Dermer 267 O'Connor St Kegan 267 O'Connor St Dollin 267 O'Connor St Halliday 267 O'Connor St Krane 267 O'Connor St Comerton 267 O'Connor St Townsend 267 O'Connor St Cooper 267 O'Connor St Daryawish 267 O'Connor St Wilson 267 O'Connor St Maloley 267 O'Connor St Mercer 267 O'Connor St Stanners 267 O'Connor St Yau 267 O'Connor -

OTTAWA ONTARIO Accelerating Success

#724 BANK STREET OTTAWA ONTARIO Accelerating success. 724 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS 6 PROPERTY OVERVIEW 8 AREA OVERVIEW 10 FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS 14 CONTENTS ZONING 16 724 THE PROPERTY OFFERS DIRECT POSITIONING WITHIN THE CENTRE OF OTTAWA’S COVETED GLEBE NEIGHBOURHOOD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 724 Bank Street offers both potential investors and owner- Key Highlights occupiers an opportunity to acquire a character asset within • Rarely available end unit character asset within The Glebe Ottawa’s much desired Glebe neighbourhood. • Attractive unique facade with signage opportunity At approximately 8,499 SF in size, set across a 3,488 SF lot, this • Flagship retail opportunity at grade 1945 building features two storeys for potential office space and • Excellent locational access characteristics, just steps from OC / or retail space. 5,340 SF is above grade, 3,159 SF SF is below transpo and minutes from Highway 417 grade (As per MPAC). • Strong performing surrounding retail market with numerous local and national occupiers Located on Bank Street at First Avenue, approximately 600 • Attractive to future office or retail users, private investors and meters north of the Lansdowne, the Property is encompassed by surrounding landholders character commercial office space, a supportive residential and • Excellent corner exposure condominium market and a destination retail and dining scene in Ottawa. ASKING PRICE: $3,399,000 724 BANK STREET 5 INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS A THRIVING URBAN NODE OFFERING TRENDY SHOPPING, DINING AND LIVING IN OTTAWA, THE PROPERTY IS SURROUNDED BY AN ECLECTIC MIX OF RETAILERS, RESTAURANTS AND COFFEE SHOPS. The Property presents an opportunity for an An end-unit asset, complete with both First Avenue and Drawn to The Glebe by its notable retail and dining scene, investor or owner-occupier to acquire a rarely available, Bank Street frontage, the Property presents an exceptional commercial rents within the area have continued to rise character asset in The Glebe neighbourhood of Ottawa. -

For Lease #724 Bank Street

FOR LEASE #724 BANK STREET OTTAWA ONTARIO Accelerating success. 724 Key Highlights: • Rarely available end unit character space within The Glebe PROPERTY • Attractive unique facade with signage opportunity • Flagship retail opportunity at grade • Attractive to future office or retail users • Close proximity to Ottawa’s arterial routes including, Bank Street, OVERVIEW Bronson Avenue, and Queen Elizabeth Driveway • Easy access to East/West Highway 417 at Metcalfe Street Excellent corner exposure, 724 Bank Street is well positioned in the established Glebe neighbourhood of Ottawa, appealing to a broad base of tenants. Surrounded by improved historic buildings with detailed architecture, giving the immediate • Immediate area serviced by OC public transit, providing access to area a unique look. Ottawa’s robust labour pool At approximately 8,499 SF in size, set across a 3,488 SF lot, this 1945 building features two storeys for potential office • Recently upgraded with new roof, new hot water tank and boiler space and / or retail space. 5,340 SF is above grade, 3,159 SF is below grade (As per MPAC). • Available immediately Located on Bank Street at First Avenue, approximately 600 meters north of the Lansdowne, the property is encompassed by character commercial office space, a supportive residential and condominium market and a destination retail and dining scene in Ottawa. ASKING RENTAL RATE: $155,000/YEAR TRIPLE NET 2 724 BANK STREET PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Municipal Address 724 Bank Street, Ottawa, ON No. of Floors Two (2) Location Bank Street -

Alexandra Bridge Replacement Project

Alexandra Bridge Replacement Project PUBLIC CONSULTATION REPORT OCTOBER TO DECEMBE R , 2 0 2 0 Table of Contents I. Project description .................................................................................................................................... 3 A. Background ........................................................................................................................................ 3 B. Project requirements ..................................................................................................................... 3 C. Project timeline ................................................................................................................................ 4 D. Project impacts ............................................................................................................................. 4 II. Public consultation process............................................................................................................ 5 A. Overview .............................................................................................................................................. 5 a. Consultation objectives ............................................................................................................ 5 b. Dates and times ............................................................................................................................ 5 B. Consultation procedure and tools .......................................................................................... -

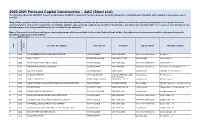

2021 Forecast Capital Construction - AAC (Short List) the List Below Shows the 2020/2021 Projects on Which Your Feedback Is Requested

2020-2021 Forecast Capital Construction - AAC (Short List) The list below shows the 2020/2021 projects on which your feedback is requested. For these projects, the City of Ottawa Accessibility Design Standards will be applied to the greatest extent possible. Many of these projects contain exterior paths of travel for which the potention provision and placement of a rest area will be decided in the upcoming design phase of the project based on numerous factors, such as the results of the consultation, available space, property requirements, location of transit stops, and volume of pedestrian traffic. If a rest area is to be provided on an individual project, its design would follow the Accessibility Design Standards. Many of the projects listed have existing on-street parking areas which are available to Accessible Parking Permit holders. Any adjustments to those areas would be determined during the upcoming design phase of the project. May 07, 2020 Location Description From Street To Street Type of Work Ward Description Item Year Construction Construction 1 2020 OLD GREENBANK ROAD AND KILBIRNIE DRIVE NOT AVAILABLE NOT AVAILABLE Intersection Modifications Jan Harder - 3 2 2020 VARLEY DRIVE BEAVERBROOK LANE CARR CRESECENT New Sidewalks Jenna Sudds - 4 3 2020 MARCH ROAD AND STREET C AND E NOT AVAILABLE NOT AVAILABLE Intersection Modifications Eli El-Chantiry - 5 4 2020 FERNBANK ROAD AND COPE DRIVE NOT AVAILABLE NOT AVAILABLE Intersection Modifications Glen Gower - 6, Scott Moffatt - 21 5 2020 CEDARVIEW ROAD RICHMOND ROAD BRUIN ROAD Cycling -

Project Brief Contents Terminology and Acronyms

1500 Bronson Avenue Request for Proposal Page 1 of 225 Rehabilitation Project EJ078-193032/A PROJECT BRIEF CONTENTS TERMINOLOGY AND ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................... 5 PD 1 PROJECT INFORMATION .................................................................................................... 12 1. Project Information .................................................................................................................. 12 1.1 Project Identification ................................................................................................... 12 PD 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ...................................................................................................... 13 2. Project Description .................................................................................................................. 13 2.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................ 13 2.2 Building Users ............................................................................................................ 13 2.3 Classified Heritage Building........................................................................................ 13 2.4 Cost ............................................................................................................................ 14 2.5 Schedule .................................................................................................................... -

Summary of Submissions, Subdivison Zoning 7000 Campeau

Summary of Written and Oral Submissions Plan of Subdivision and Zoning By-law Amendment – 7000 Campeau Drive (ACS2020-PIE-PS-0109) Note: This is a draft Summary of the Written and Oral Submissions received in respect of Plan of Subdivision and Zoning By-law Amendment – 7000 Campeau Drive (ACS2020- PIE-PS-0109), prior to City Council’s consideration of the matter on December 9, 2020. The final Summary will be presented to Council for approval at its meeting of January 27, 2021, in the report titled ‘Summary of Oral and Written Public Submissions for Items Subject to the Planning Act ‘Explanation Requirements’ at the City Council Meeting of December 9, 2020’. Please refer to the ‘Bulk Consent’ section of the Council Agenda of January 27, 2021 to access this item. In addition to those outlined in the Consultation Details section of the report, the following outlines the written and oral submissions received between the publication of the report and prior to City Council’s consideration: Number of delegations/submissions Number of delegations at Committee: 16 Number of written submissions received by Planning Committee between November 16 (the date the report was published to the City’s website with the agenda for this meeting) and November 26, 2020 (committee meeting date): 13 Primary concerns (concerns about the application / i.e. in support of the staff recommendations), by individual The following 10 persons spoke as individuals and as representatives of the Kanata Greenspace Protection Coalition (KGPC): Des Adam; Chris Teron; James Brockbank; Cyril Leeder; Terry Matthews; Denis A. Bourque; Dr. Heather McNairn; Dr.