Citrus By-Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

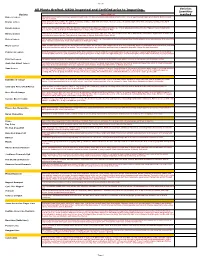

Tomorrow's Harverst Variety Info Common Name

Tomorrow's Harverst Variety Info Common Name Botanical Name Variety Description Chill Pollinator Ripens Flesh Ornamental citrus tree with distinctive aroma under dense canopy of leaves. AKA the Key Lime Citrus aurantiifolia Bartender's lime. No chill required No pollinator required Classic aromatic, green fruit grows well in contianers. Excellent specimen plant. Fragrant Mexican Lime Citrus aurantiifolia Unlikespring blooms.other citrus fruit, the sweetest part of the kumquat is the peel. Ripe fruit is stored No chill required No pollinator required on the tree! Pick whenever you feel like a great tasting snack. Yields little fruits to pop Nagami Kumquat Citrus fortunella 'Nagami' right into your mouth. No chill required No pollinator required Kaffir Lime Citrus hystrix Unique bumpy fruits are used in Thai cooking. Zest of rind or leaves are used. No chill required No pollinator required Best in patio containers, evergreen foliage and fragrant flowers. Harvest year round in Kaffir Dwarf Lime Citrus hystrix Dwarf frost free areas. No chill required No pollinator required Bearss Lime Citrus latifolia Juicy, seedless fruit turns yellow when ripe. Great for baking and juicing. No chill required No pollinator required Yellow flesh Eureka Lemon Citrus limon 'Eureka' Reliable, consistent producer is most common market lemon. Highly acidic, juicy flesh. No chill required No pollinator required Classic market lemon, tart flavor, evergreen foliage and fragrant flowers. Vigorous Eureka Dwarf Lemon Citrus limon 'Eureka' Dwarf productive tree. No chill required No pollinator required Lisbon Lemon Citrus limon 'Lisbon' Productive, commercial variety that is heat and cold tolerant. Harvest fruit year round. No chill required No pollinator required Meyer Improved Lemon Citrus limon 'Meyer Improved' Hardy, ornamental fruit tree is prolific regular bearer. -

Cuban Tree Frog He's a Bad Boy!!

Dear Extension Friends, August 2014 We hope you are enjoying your summer by taking the proper precau- Inside this issue: tions to prevent sunburn and heat exhaustion. If you find yourself needing a Cuban Treefrog 1 break from the heat, you are welcome to visit Dr. Kyle Brown for gardening information and advice in the comfort of the air-conditioned office (1pm to Citrus Species and 2 5pm, Monday through Friday). Hybrids Best Regards, Join Us On Facebook! Bamboo Control 3 UF IFAS Extension Baker County Garden Spot Fruit Tree 4 Alicia R. Lamborn https://www.facebook.com/ Calendar: August Horticulture Extension Agent UFIFASBakerCountyGardenSpot Baker County Extension Service CUBAN TREE FROG HE’S A BAD BOY!! A Cuban Tree Frog has been found in Baker County recently. Please keep an eye out for this invasive pest as he eats native tree frogs and smaller lizards and snakes. Should you find one, bring to the Extension Office for positive identification. Make a Tree Frog Hangout from a 3 foot length of 1.25 inch diameter PVC pipe, stand upright in ground near house or shrubs. Check it often to see if you have this Bad Boy! For more information on the Cuban tree frog, see the following UF/ IFAS publications: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw259 http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw346 Photo Credits: Steven Johnson, University of Florida The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) is an Equal Opportunity Institution authorized to provide research, educational information, and other services only to individ- uals and institutions that function with non-discrimination with respect to race, creed, color, religion, age, disability, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, national origin, political opinions, or affiliations. -

2019 Full Provisional List

Sheet1 All Plants Grafted. USDA inspected and Certified prior to Importing. Varieties Quantities Variety Description required Baboon Lemon A Brazilian lemon with very intense yellow rind and flesh. The flavour is acidic with almost a hint of lime. Tree is vigorous with large green leaves. Both tree and fruit are beautiful. Bearss Lemon 1952. Fruit closely resembles the Lisbon. Very juicy and has a high rind oil content. The leaves are a beautiful purple when first emerging, turning a nice dark green. Fruit is ready from June to December. Eureka Lemon Fruit is very juicy and highly acidic. The Eureka originated in Los Angeles, California and is one of their principal varieties. It is the "typical" lemon found in the grocery stores, nice yellow colour with typical lemon shape. Harvested November to May Harvey Lemon 1948.Having survived the disastrous deep freezes in Florida during the ’60’s and ’70’s. this varieties is known to withstand cold weather. Typical lemon shape and tart, juicy true lemon flavour. Fruit ripens in September to March. Self fertile. Zones 8A-10. Lisbon Lemon Fruit is very juicy and acic. The leaves are dense and tree is very vigorous. This Lisbon is more cold tolerant than the Eureka and is more productive. It is one of the major varieties in California. Fruit is harvested from February to May. Meyer Lemon 1908. Considered ever-bearing, the blooms are very aromatic. It is a lemon and orange hybrid. It is very cold hardy. Fruit is round with a thin rind. Fruit is juicy and has a very nice flavour, with a low acidity. -

Reaction of Types of Citrus As Scion and As Rootstock to Xyloporosis Virus

ARY A. SALIBE and SYLVIO MOREIRA Reaction of Types of Citrus as Scion and as Rootstock to Xyloporosis Virus THEVIRUS of xyloporosis (cachexia) (2,4, 10) is widespread in many commercial varieties of citrus ( 1, 5, 6, 8).For this reason, it is of special interest to know the reaction between it and various types of citrus that are presently used as rootstocks or may eventually be so used. This paper reports the results of tests conducted to determine this reaction for a number of different types of citrus. Materials and Methods In September, 1960, 2-year-old Cleopatra mandarin [Citrus reshni (Engl.) Hort. ex Tanaka] seedlings in the nursery were inoculated with xyloporosis virus by budding each seedling with three buds from a single old-line Bargo sweet orange [C. sinensis (L.) Osbeck] tree on Dancy tan- gerine (C. tangerina Hort. ex Tanaka) rootstock exhibiting the gummy- peg and wood-pitting type of xyloporosis symptoms. This tree was known to be carrying both xyloporosis and tristeza viruses but neither psorosis nor exocortis viruses. Two months later, each of two of these seedlings was budded just above the inoculating bud with one or another of 122 different types of citrus, each bud being taken from a tree of a nucellar line, except in the case of the monoembryonic types. Identical numbers of non-inocu- lated Cleopatra mandarin seedlings were budded with these citrus types to serve as control plants. All seedlings were cut back to allow the buds to sprout. They were inspected periodically by taking out a strip of bark at the bud-union, the last inspection being made 33 months after inocula- tion. -

Holdings of the University of California Citrus Variety Collection 41

Holdings of the University of California Citrus Variety Collection Category Other identifiers CRC VI PI numbera Accession name or descriptionb numberc numberd Sourcee Datef 1. Citron and hybrid 0138-A Indian citron (ops) 539413 India 1912 0138-B Indian citron (ops) 539414 India 1912 0294 Ponderosa “lemon” (probable Citron ´ lemon hybrid) 409 539491 Fawcett’s #127, Florida collection 1914 0648 Orange-citron-hybrid 539238 Mr. Flippen, between Fullerton and Placentia CA 1915 0661 Indian sour citron (ops) (Zamburi) 31981 USDA, Chico Garden 1915 1795 Corsican citron 539415 W.T. Swingle, USDA 1924 2456 Citron or citron hybrid 539416 From CPB 1930 (Came in as Djerok which is Dutch word for “citrus” 2847 Yemen citron 105957 Bureau of Plant Introduction 3055 Bengal citron (ops) (citron hybrid?) 539417 Ed Pollock, NSW, Australia 1954 3174 Unnamed citron 230626 H. Chapot, Rabat, Morocco 1955 3190 Dabbe (ops) 539418 H. Chapot, Rabat, Morocco 1959 3241 Citrus megaloxycarpa (ops) (Bor-tenga) (hybrid) 539446 Fruit Research Station, Burnihat Assam, India 1957 3487 Kulu “lemon” (ops) 539207 A.G. Norman, Botanical Garden, Ann Arbor MI 1963 3518 Citron of Commerce (ops) 539419 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3519 Citron of Commerce (ops) 539420 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3520 Corsican citron (ops) 539421 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3521 Corsican citron (ops) 539422 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3522 Diamante citron (ops) 539423 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio CA 1966 3523 Diamante citron (ops) 539424 John Carpenter, USDCS, Indio -

Improvement of Subtropical Fruit Crops: Citrus

IMPROVEMENT OF SUBTROPICAL FRUIT CROPS: CITRUS HAMILTON P. ÏRAUB, Senior Iloriiciilturist T. RALPH ROBCNSON, Senior Physiolo- gist Division of Frnil and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, Bureau of Plant Tndusiry MORE than half of the 13 fruit crops known to have been cultivated longer than 4,000 years,according to the researches of DeCandolle (7)\ are tropical and subtropical fruits—mango, oliv^e, fig, date, banana, jujube, and pomegranate. The citrus fruits as a group, the lychee, and the persimmon have been cultivated for thousands of years in the Orient; the avocado and papaya were important food crops in the American Tropics and subtropics long before the discovery of the New World. Other types, such as the pineapple, granadilla, cherimoya, jaboticaba, etc., are of more recent introduction, and some of these have not received the attention of the plant breeder to any appreciable extent. Through the centuries preceding recorded history and up to recent times, progress in the improvement of most subtropical fruits was accomplished by the trial-error method, which is crude and usually expensive if measured by modern standards. With the general accept- ance of the Mendelian principles of heredity—unit characters, domi- nance, and segregation—early in the twentieth century a starting point was provided for the development of a truly modern science of genetics. In this article it is the purpose to consider how subtropical citrus fruit crops have been improved, are now being improved, or are likel3^ to be improved by scientific breeding. Each of the more important crops will be considered more or less in detail. -

New and Noteworthy Citrus Varieties Presentation

New and Noteworthy Citrus Varieties Citrus species & Citrus Relatives Hundreds of varieties available. CITRON Citrus medica • The citron is believed to be one of the original kinds of citrus. • Trees are small and shrubby with an open growth habit. The new growth and flowers are flushed with purple and the trees are sensitive to frost. • Ethrog or Etrog citron is a variety of citron commonly used in the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles. The flesh is pale yellow and acidic, but not very juicy. The fruits hold well on the tree. The aromatic fruit is considerably larger than a lemon. • The yellow rind is glossy, thick and bumpy. Citron rind is traditionally candied for use in holiday fruitcake. Ethrog or Etrog citron CITRON Citrus medica • Buddha’s Hand or Fingered citron is a unique citrus grown mainly as a curiosity. The six to twelve inch fruits are apically split into a varying number of segments that are reminiscent of a human hand. • The rind is yellow and highly fragrant at maturity. The interior of the fruit is solid rind with no flesh or seeds. • Fingered citron fruits usually mature in late fall to early winter and hold moderately well on the tree, but not as well as other citron varieties. Buddha’s Hand or Fingered citron NAVEL ORANGES Citrus sinensis • ‘Washington navel orange’ is also known • ‘Lane Late Navel’ was the first of a as the Bahia. It was imported into the number of late maturing Australian United States in 1870. navel orange bud sport selections of Washington navel imported into • These exceptionally delicious, seedless, California. -

WO 2013/077900 Al 30 May 2013 (30.05.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/077900 Al 30 May 2013 (30.05.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, A23G 3/00 (2006.01) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, (21) International Application Number: HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, PCT/US20 12/028 148 KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (22) International Filing Date: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, 7 March 2012 (07.03.2012) OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, (25) Filing Language: English TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 13/300,990 2 1 November 201 1 (21. 11.201 1) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, (72) Inventor; and TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, (71) Applicant : CROWLEY, Brian [US/US]; 104 Palisades DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, Avenue, #2B, Jersey City, New Jersey 07306 (US). -

CITRUS the Botanictanic Garden of the Universitat De València

Botanical monographs CITRUS The Botanictanic Garden of the Universitat de València Gema Ancillo Alejandro Medina Botanical Monographs CITRUS Gema Ancillo and Alejandro Medina Botanical Monographs. Jardín Botánico de la Universitat de València Volume 2: Citrus Texts ©: Gema Ancillo and Alejandro Medina Introduction ©: Isabel Mateu Images and illustrations ©: Gema Ancillo, Alejandro Medina and José Plumed Publication ©: Universitat de València E. G. Director of the monographic series: Isabel Mateu Technical director: Martí Domínguez Graphic design and layout: José Luis Iniesta Revision and correction: José Manuel Alcañiz Translation: Fabiola Barraclough, Interglobe Language Photographs: José Plumed, Gema Ancillo, Alejandro Medina, Miguel Angel Ortells and José Juarez Cover photograph: Miguel Angel Ortells Printed by: Gráfi cas Mare Nostrum, S. L. Legal Deposit: V-439-2015 ISBN: 978-84-370-9632-2 Index Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 The Aurantioideae Subfamily....................................................................................................11 – General description ...............................................................................................................................11 – Trunk ..................................................................................................................................................... 12 – Roots .....................................................................................................................................................13 -

Limonoids from Citrus Chemistry, Anti-Tumor Potential, And

Journal of Functional Foods 75 (2020) 104213 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Functional Foods journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jff Limonoids from Citrus: Chemistry, anti-tumor potential, and other T bioactivities Yu-Sheng Shia,b,1, Yan Zhangc,1, Hao-Tian Lia, Chuan-Hai Wud, Hesham R. El-Seedie,f, ⁎ ⁎ Wen-Kang Yed,g, Zi-Wei Wangd, Chun-Bin Lia, Xu-Fu Zhangc, , Guo-Yin Kaib, a Key Laboratory of Biotechnology and Bioresources Utilization, Educational of Minister, College of Life Science, Dalian Nationalities University, Dalian 116600, China b Laboratory of Medicinal Plant Biotechnology, College of Pharmacy, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou 311402, China c School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China d Department of Ocean Science, Division of Life Science and Hong Kong Branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong, China e Pharmacognosy Group, Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Uppsala University, Biomedical Centre, Uppsala 75 123, Sweden f International Research Center for Food Nutrition and Safety, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, 212013, China g SZU-HKUST Joint Ph.D. Program in Marine Environmental Science, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518061, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Citrus limonoids are tetranortriterpenoids compounds mainly found in oranges, lemons, grapefruits, and other Rutaceae fruits of Citrus. They are proved to be the leading cause of bitterness in Citrus fruits and are mainly consumed for Citrus therapeutic purposes and as food. Numerous studies have focused on Citrus limonoids and intend to develop new Limonoid chemotherapeutic or complementary medicine in recent years. -

Planting, Growing, and Harvesting Lemon, Orange, Mosambi, Sweet

How to grow Citrus Fruits: Planting, Growing, and Harvesting Lemon, Orange, Mosambi, Sweet Lime, Mandarin, Grapefruit, Kinnow Mandarin, Sour Lime, Pummelo, Orchad www.entrepreneurindia.co www.entrepreneurindia.co www.entrepreneurindia.co www.entrepreneurindia.co www.entrepreneurindia.co Table of Contents 1. Botanical Classification Classification of Genus Citrus Criteria for Citrus Classification Different Classification Subgenus Eucitrus (10 Species) Subgenus 2. Papeda (6 Species) Subgenera 1. Archicitrus (5 Sections, 98 Species) Subgenera 2. Meta Citrus (3 Sections, 46 Species) Others of Somewhat Doubtful Classification Information on Important Citrus Fruits Subgenus Fucitrus (Edible Citrus Fruits) Acid Group Citrus Medica Linn. (Citron) www.entrepreneurindia.co Citrus Lemon Burm (Lemon) Citrus Aurantifolia Swingle (Acid Lime) Citrus Latifolia Tanaka (Tahiti or Persian Lime) Citrus Limettioides Tanaka (Sweet Lime) Citrus Jambhiri Lush (Rough Lemon; Jambiri) Citrus Limetta Risso (Limetta of the Mediterranean) Citrus Karna Raff (Kharna Khatta) Citrus Limonia Osbeck (Rangpur Lime) Citrus Pennivesiculata Tanaka (Gajanimma) Orange Group Citrus Aurantium Linn (Sour, Bigarade or Soville Orange) Citrus Sinensis Osbeck (Sweet Orange) Citrus Myrtifolia Raffinesque Citrus Bergemia Risso (Bargmot Orange) Citrus Natsudaidai Hayata www.entrepreneurindia.co Pumelo-Grapefruit Group Mandarin Group Citrus Reticulate Blance (loose skinned orange or Santra of India) Citrus Unshiu M (Satsuma Mandarin) Citrus Deliciosa Tenore Citrus Nobilis Loureio (King Mandarin) Citrus Reshni Tanaka (Spice Mandarin) Citrus Medurensis Lou (Calamondin) Citrus Madaraspatana Tanaka Subgenus Papeda : (Inedible Citrus Fruits) Eupapeda Citrus Citrus Macroptera (Metanewsian Papeda) Papeda Citrus Citrus Ichangensis Citrus Iatipes (Khasi Papeda) www.entrepreneurindia.co Kumquats Fortunella Margarita Swingle (Nagami or Oval Kumquat) Fortunella Japonica Swingle (Marumi or Round Kumquat) Fortunella Crassiflora Swingle (Meiwa Kumquat) Fortunella Bindsii Swingle (Hong Kong wild Kumquat) Poncirus Trifoliata L. -

A Review on Citrus – “The Boon of Nature”

Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 18(2), Jan – Feb 2013; nᵒ 04, 20-27 ISSN 0976 – 044X Review Article A Review on Citrus – “The Boon of Nature” Jaspreetkaur Sidana1*, Vipin Saini1, Sumitra Dahiya2, Parminder Nain1, Suman Bala1 1M.M. College of Pharmacy, MM University, Mullana (Ambala)-133207, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutical Science, G.J. University, Hissar (Haryana), India. Accepted on: 17-12-2012; Finalized on: 31-01-2013. ABSTRACT Citrus occupies a place of considerable importance in the fruit economy of the country. Citrus fruits are economically important with a large scale production of both the fresh fruit and processed products. Citriculture as a garden industry existed for centuries in India. It comprises the third largest fruit industry. Among the Citrus fruits oranges contribute to roughly 80 percent of the world’s Citrus fruit production. There is strong, consistent evidence that a high intake of fruit and vegetables protects against various cancers. Citrus fruits are recognized as an important component of the human diet, providing a variety of constituents important to human nutrition, including vitamin C, folic acid, potassium, flavonoids, coumarins, pectin and dietary fibres. Citrus flavonoids have a broad spectrum of biological activities including antibacterial, antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticancer cardiovascular, analgesic, antiinflammatory, antianxiety etc. This report details the health benefits of Citrus, especially in cancer and the active components which are thought to produce these health benefits, their mechanisms