William Sharp (Fiona Macleod)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quadro Conoscitivo Dello Stato Del Territorio

COMUNITA’ EUROPEAREGIONE SICILIANA COMUNE DI PATERNO’ PIANO STRATEGICO AREA ETNEA PATERNÒ / ADRANO / BELPASSO / BIANCAVILLA / BRONTE / CALATABIANO / CAMPOROTONDO ETNEO / CASTIGLIONE DI SICILIA / FIUMEFREDDO DI SICILIA / GIARRE / LINGUAGLOSSA / MALETTO / MANIACE / MASCALI / MILO / MOTTA SANT’ANASTASIA / NICOLOSI / PEDARA / PIEDIMONTE ETNEO / RAGALNA / RANDAZZO / RIPOSTO / SANT’ALFIO / SANTA MARIA DI LICODIA / SANTA VENERINA / TRECASTAGNI / VIAGRANDE / ZAFFERANA ETNEA / "-!3+#,2-"#,'2'4- QUADRO CONOSCITIVO DELLO STATO DEL TERRITORIO allegato n. 01 OPERA ARGOMENTO DOC. E PROG. FASE REVISIONE P U PA SQ02 G 1 CARTELLA: FILE NAME: NOTE: PROT. SCALA: 01 PU PA SQ02_G1_4163.pdf 4163 5 4 3 2 1 REVISIONE 16/12/2011LUTRI LUTRI ALAGNA 0 EMISSIONE 27/09/2011LUTRI LUTRI ALAGNA REV. DESCRIZIONE DATA REDATTO VERIFICATO APPROVATO Il presente progetto è il frutto del lavoro dei professionisti associati in Politecnica. A termine di legge tutti i diritti sono riservati. E' vietata la riproduzione in qualsiasi forma senza autorizzazione di POLITECNICA Soc. Coop. Politecnica aderisce al progetto Impatto Zero di Lifegate.R Ing. M. Scaccianoce Le emissioni di CO2 di questo progetto sono compensate con la creazione di nuove foreste. 1. MACROAMBITOTERRITORIALEEDAMBIENTALE..........................................3 1.1Caratteristicheerisorseambientalienaturalidell'areaetnea............................3 1.1.1 Ilsistemamacrogeografico..........................................................................3 1.1.2 Laflora.........................................................................................................5 -

Rural Development Between “Institutional Spaces” and “Spaces of Resources and Vocations”: Park Authorities and Lags in Sicily

TOPIARIUS • Landscape studies • 6 Concetta Falduzzi1 Doctor of Political and Social Science, Expert in local development policies Giuseppe Sigismondo Martorana1 M. Sc. In Law University of Catania, Department of Political and Social Science Rural development between “institutional spaces” and “spaces of resources and vocations”: Park Authorities and LAGs in Sicily Abstract This paper addresses the subject of the reference frames of territori- alisation processes determined by local development initiatives. Its purpose is to offer a survey on a central issue: which spatial frames of reference influence or justify the choices of LAGs in the defini- tion and delimitation of local development spaces. The paper is about the case of Sicily, presenting some possible in- terpretations of an evolution of the development space from “insti- tutional space” to “space of resources and vocations”. The paper will highlight the relation between the spaces of natural parks and the spaces of LAGs in the Participatory Local Development Strate- gies. Keywords: territorialisation, local development, LAGs, natural park, Participatory Local Development Strategies Introduction It has been argued [Martorana 2017] that the landscape resources are fundamental to the development of tourism in rural areas; that Park Authorities, as institutional bodies responsible for the environmental and landscape protection of 1, For the purpose of the attribution of the two Authors‟ contributions to this article, it is speci- fied that C. Falduzzi is the Author of the paragraphs 'Introduction'. 'The „objects‟ of observa- tion: LAGs and regional natural parks between development and protection' and 'Rural devel- opment territories and natural parks in Sicily: two geographies compared'. G.S. -

Fiona Macleod”

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 3: 1900-1905 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and F. H F. What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent introductory secti ons – so balanced and judicious and informati ve – what emerges is “Fiona Macleod” an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how ALLORAN fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it happen. Volume 3: 1900-1905 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

Ufficio Comunale Di Protezione Civile

COMUNE DI MALETTO PROVINCIA DI CATANIA UFFICIO COMUNALE DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE PIANO COMUNALE DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE - RISCHIO SISMICO - RISCHIO IDROGEOLOGICO - RISCHIO DI INVASIONE LAVICA E DI RICADUTA DI CENERI VULCANICHE - RISCHIO INCENDI DI INTERFACCIA COMUNE DI MALETTO PREMESSA L’amministrazione del Comune di Maletto, nel rispetto della legislazione nazionale e regionale sulla Protezione Civile, col presente documento si dota di un Piano di Emergenza Comunale di Protezione Civile redatto secondo le linee guida Augustus elaborate dal Servizio Pianificazione ad Attività Addestrative del Dipartimento Nazionale di Protezione Civile e dalla Direzione Centrale della Protezione Civile e dei Servizi Logistici del Ministero dell’Interno. In particolare, sono state seguite anche le linee guida impartite dal Dipartimento Regionale di Protezione Civile della Sicilia e di cui vengono allegate n. 9 schede dettagliate. L’ex Piano di Protezione Civile era stato approntato nel 1997 e poi aggiornato nel 2002. RIFERIMENTI NORMATIVI Si ritiene necessario accennare al quadro normativo vigente in materia di Protezione Civile, al fine di evidenziare i parametri giuridici di riferimento nell’ambito della pianificazione di emergenza. L’art. 15 della Legge 225 del 24 febbraio 1992 e s.m.e.i. e l’art. 108 del D. Lgs. n. 112 del 31 marzo 1998 danno pieno potere al Sindaco per la definizione di una struttura comunale di protezione civile che possa fronteggiare situazioni di emergenza nell’ambito del territorio comunale. La Legge n. 401/2001 assegna tutti i poteri di gestione del Servizio Nazionale di Protezione Civile al Presidente del Consiglio e, per delega di quest’ultimo, al Ministro dell’Interno e quindi al Dipartimento Nazionale di Protezione Civile. -

Official Journal C 257 of the European Union

Official Journal C 257 of the European Union Volume 62 English edition Information and Notices 31 July 2019 Contents II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2019/C 257/01 Commission notice — Guidelines for the implementation of the single digital gateway Regulation — 2019-2020 work programme ................................................................................................. 1 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2019/C 257/02 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 14 V Announcements PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY European Commission 2019/C 257/03 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9397 — Mirova/GE/Desarrollo Eólico Las Majas) — Candidate case for simplified procedure (1) ................................................................................ 15 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. 2019/C 257/04 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9418 — Temasek/RRJ Masterfund III/Gategroup) (1) ....... 17 OTHER ACTS European Commission 2019/C 257/05 Publication of an application for registration of a name pursuant to Article 50(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs ........................................................................................................ -

Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale CATANIA ELENCO SEDI

Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale CATANIA ELENCO SEDI aree a verde Terreno Alberi Città Specificità Indirizzo mq mq Nr. Note Referente Tecnico Telefono e.mail Biancavilla PO Ospedale Via C. Colombo - Biancavilla 8.000 Biancavilla PO Ospedale Via Marconi - Biancavilla 600 Biancavilla PO Centro di Recupero Via M. SS Addolorata - Biancavilla 2.000 Paternò PO Ospedale Via Livorno - Paternò 3.600 Paternò Distretto di Paternò ex Poliambulatorio Via Verga - Paternò 50 Belpasso Distretto di Paternò Poliambulatorio P.zza Municipio - Belpasso 100 095 7716345 Cell. 333 9659860 [email protected] Ragalna Distretto di Paternò Poliambulatorio Via Giuffrida - Ragalna 300 Geom. Coco - Geom. Alberio 095 7716341 Cell. 340 6330814 [email protected] S. M. di Licodia Distretto di Adrano Poliambulatorio Via Verdi - S.Maria di Licodia 100 Adrano Distretto di Adrano ex PO di Adrano Poliamb. ex PO 10 Biancavilla Via della Montagna - Biancavilla 2.923 Terreno agricolo Paternò c/da Poggio Russello - Paternò 122.176 Terreno agricolo Paternò c/da Schettino -Paternò 1.790 Terreno agricolo Paternò c/da Rotondella - Paternò 58.461 Terreno agricolo Caltagirone PO Ospedale Via Portosalvo - Caltagirone 9.400 Caltagirone Distretto di Caltagirone Serv. Distr. P.zza Marconi - Caltagirone 100 Caltagirone Distretto di Caltagirone DSM via Escuriales - Caltagirone 320 Caltagirone PO S. Pietro 90.000 Terreno agricolo Caltagirone CTA S. Pietro 10.160 Terreno agricolo Caltagirone Uliveto a S. Pietro 96.800 Terreno agricolo Caltagirone Vigneto a S. Pietro 8.410 Terreno agricolo Grammichele Distretto di Caltagirone Poliambulatorio Ex PO di Grammichele 100 0933 39650 Cell. 336 398780 [email protected] Licodia Distretto di Caltagirone Poliambulatorio Licodia Eubea 0 Geom. -

Bando Comune Camporotondo Etneo

PROVINCIA REGIONALE DI CATANIA denominata “Libero Consorzio Comunale” ai sensi della L.R. n. 8/2014 3° Dipartimento Sviluppo Economico e Socio - Culturale 3° Servizio Attività Economico - Produttive e Trasporti Ufficio Trasporti Prot. n. 41316 Gravina di Catania, li 25.06.2015 Class. 2.3.8 Via Zangrì, n. 8 ALLEGATI: 6 OGGETTO : Richiesta di pubblicazione del bando di pubblico concorso, per soli titoli, per l’assegnazione di n. 3 autorizzazioni all’esercizio del servizio di noleggio autovettura con conducente, con stazionamento in rimessa nell’ambito del territorio del comune di Camporotondo Etneo . Termine perentorio per la presentazione delle istanze: 31/07/2015 Al Comune di Catania [email protected] Al Comune di Aci Bonaccorsi [email protected] Al Comune di Aci Castello [email protected] Al Comune di Aci Catena [email protected] Al Comune di Aci Sant’Antonio [email protected] Al Comune di Acireale [email protected] Al Comune di Adrano [email protected] Al Comune di Belpasso [email protected] Al Comune di Biancavilla [email protected] Al Comune di Bronte [email protected] Al Comune di Calatabiano [email protected] Al Comune di Caltagirone [email protected] Al Comune di Camporotondo Etneo [email protected] Al Comune di Castel di Iudica [email protected] Al Comune di Castiglione di -

Etna Rosso with the Potential of the Nerello Mascalese Grape Now Clear, Sicily’S Volcanic Red Wine Is on a Roll, with a Boom in Investment and Vineyard Area

PANEL TASTING Etna Rosso With the potential of the Nerello Mascalese grape now clear, Sicily’s volcanic red wine is on a roll, with a boom in investment and vineyard area. Michael Garner reports THIRTY YEARS AGO, Etna Rosso was in danger of becoming a museum piece. Following DOC recognition N Randazzo 120 in 1968, it had been barely kept alive by a few producers Castiglione – notably Barone Villagrande, Cantine Russo and the di Sicilia Taormina local co-operative Torrepalino (now a privately owned 120 Maletto Linguaglossa company), serving an almost entirely local market. But a A18 Piedimonte trickle of new interest in the late 1980s and early 1990s Etneo when Benanti and then Cottanera invested in the area, SIC I LY Bronte ETNA 114 was to become a substantial flow soon after. Mount ROSSO Sant’Alfio 284 Etna Between 2003 and 2014 the land under vine in the Riposto Simeto Milo DOC zone more than doubled, though the consorzio, Giarre founded in the early 1990s by just a few growers, predicts Zafferana that the growth rate will soon slow and peak at around a 1,000 hectares. While some of the new blood came from Adrano e S within Sicily, including well-known names like Cusumano, Biancavilla Firriato, Planeta and Tasca d’Almerita, among the first Nicolosi an Acireale e outsiders to arrive were Belgian Frank Cornelissen, Belpasso Viagrande n a Andrea Franchetti from Tuscany and American Marc de 114 Reggio Mascalucia rr Grazia at the start of the new millennium. Local families, di Calabria e Messina Aci Castello Palermo Y L dit meanwhile, have been quick to reclaim their passion for A IT e the land and wineries such as Girolamo Russo, Graci and Trapani Mount ETNA M SIC I LY Etna ROSSO Tornatore are now playing an vital part in the comeback. -

(White List) Elenco Delle Imprese Iscritte Nell'elenco Dei Fornitori, Prestatori Di Servizi Ed Esecutori Di Lavori Non Sogge

Prefettura di Catania Ufficio Territoriale del Governo Ufficio Antimafia ELENCO DELLE IMPRESE ISCRITTE NELL'ELENCO DEI FORNITORI, PRESTATORI DI SERVIZI ED ESECUTORI DI LAVORI NON SOGGETTI A TENTATIVI DI INFILTRAZIONE MAFIOSA (WHITE LIST) SEDE CODICE SECONDARIA CON DATA DI SCADENZA AGGIORNAMENTO IN RAGIONE SOCIALE SEDE LEGALE ATTIVITA' FISCALE/PARTITA RAPPRESENTANZA ISCRIZIONE ISCRIZIONE CORSO IN ITALIA IVA 0.3 SRL S. GIOVANNI LA PUNTA 5,7 05185400875 25/11/2019 25/11/2020 28 58 SECURITY SRL MISTERBIANCO 9 04495320873 08/02/2020 08/02/2021 3 P SERVIZI E LOGISTICA SRL S CAMPOROTONDO E. 8 05035320877 23/09/2019 23/09/2020 3P SRL SERVIZI TRASPORTI E LOGISTICA CATANIA 8 05356260876 28/10/2019 28/10/2020 5 NODI SNC DI LUCIFORA EMILIO & C. S.AGATA LI BATTIATI 5,7 05121870876 23/09/2019 23/09/2020 richiesto rinnovo A&C DI LOGIOCO ANTONINO & SPINALE CARLO GIUSEPPE SNC CATANIA 5,7 03383840877 08/02/2020 08/02/2021 A&G IMPIANTI SRL CATANIA 5,7 04715650877 06/05/2020 06/05/2021 A.A. SERVICE DI ANTOLINO ALESSANDRO S.GREGORIO DI CATANIA 5,7 04609310877 29/01/2019 29/01/2020 richiesto rinnovo A.B. PRIMA SRL CATANIA 5,6,7 05099860875 17/09/2019 17/09/2020 A.C.M. SRL S SANTA MARIA DI LICODIA 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 05573000873 09/01/2020 09/01/2021 A.D.R. TRASPORTI SRL MASCALUCIA 1,2,3,5,7,8 04740540879 11/07/2019 11/07/2020 A.F. SERRAMENTI S.A.S. DI VINCENZO FINOCCHIARO & C. -

The Touristic Local Systems As a Means to Re-Balance

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ruggiero, Vittorio; Scrofani, Luigi Conference Paper The Touristic Local Systems as a means to re- balance territorial differences in Sicily 45th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Land Use and Water Management in a Sustainable Network Society", 23-27 August 2005, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Ruggiero, Vittorio; Scrofani, Luigi (2005) : The Touristic Local Systems as a means to re-balance territorial differences in Sicily, 45th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Land Use and Water Management in a Sustainable Network Society", 23-27 August 2005, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/117572 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

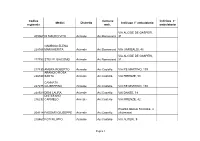

Codice Regionale Medici Distretto Comune Amb. Indirizzo I° Ambulatorio Indirizzo 2° Ambulatorio 209067 DI MAURO VITO Acireal

Codice Comune Indirizzo 2° Medici Distretto Indirizzo I° ambulatorio regionale amb. ambulatorio VIA ALCIDE DE GASPERI, 209067 DI MAURO VITO Acireale Aci Bonaccorsi 31 GAMBINO ELENA 228165 MARGHERITA Acireale Aci Bonaccorsi VIA GARIBALDI, 46 VIA ALCIDE DE GASPERI, 217793 STULLE GIACOMO Acireale Aci Bonaccorsi 31 217430 AMBRA ROBERTO Acireale Aci Castello VIA RE MARTINO, 199 ARANCIO ROSA 226180 SANTA Acireale Aci Castello VIA FIRENZE, 58 CANNATA 227275 GIUSEPPINA Acireale Aci Castello VIA RE MARTINO, 150 228529 DENI LAURA Acireale Aci Castello VAI DANTE, 18 DISTEFANO 216232 CARMELO Acireale Aci Castello VIA FIRENZE, 42 PIAZZA DELLE SCUOLE, 2 209114 FASSARI GIUSEPPE Acireale Aci Castello (Acitrezza) 218467 FOTI FILIPPO Acireale Aci Castello VIA AUTERI, 9 Pagina 1 Codice Comune Indirizzo 2° Medici Distretto Indirizzo I° ambulatorio regionale amb. ambulatorio GIUFFRIDA MARIA 219517 SANTA Acireale Aci Castello VIA TRIPOLI, 91 219130 LEOTTA FRANCESCO Acireale Aci Castello VICO ANFORA, 11 219209 MAMMINO IGNAZIO Acireale Aci Castello VIA TRIPOLI, 242 MUSUMECI 216789 SEBASTIANO Acireale Aci Castello VIA RE MARTINO, 199 221811 PARADISI VINCENZA Acireale Aci Castello VIA MOLLICA, 11 225699 PENNISI SEBASTIANO Acireale Aci Castello VIA TRIPOLI, 154 216164 RICCA SEBASTIANO Acireale Aci Castello VIA RE MARTINO, 79 216870 STRANO VINCENZO Acireale Aci Castello VIA RE MARTINO, 199 209249 AMICO FRANCESCO Acireale Aci S.Antonio VIA ROMA, 68 219448 D'AGATA ROBERTO Acireale Aci S.Antonio VIA LAVINA, 385 226373 D'AGOSTINO MIRELLA Acireale Aci S.Antonio VIA S.M. LA STELLA, 124 220465 DI SALVO ROBERTO Acireale Aci S.Antonio VIA SPIRITO SANTO, 93 Pagina 2 Codice Comune Indirizzo 2° Medici Distretto Indirizzo I° ambulatorio regionale amb. -

Dipartimento Regionale

Assemblea Territoriale Idrica ATO 2 - CATANIA ALLEGATO A DISCIPLINARE ALLEGATO ALL’AVVISO PER INDAGINE DI MERCATO FINALIZZATA ALL’INDIVIDUAZIONE DI UN SOGGETTO ESPERTO, ALTAMENTE QUALIFICATO NEL SETTORE DELLA DEPURAZIONE, CUI CONFERIRE L’INCARICO DI VERIFICARE L’ADEGUATEZZA DEL PROCESSO DEPURATIVO ED IL CORRETTO DIMENSIONAMENTO DELLE DIFFERENTI SEZIONI DEGLI IMPIANTI DI DEPURAZIONE, NELLA FASE ISTRUTTORIA DEI PROGETTI FINALIZZATI AL SUPERAMENTO DELLA PROCEDURA D’INFRAZIONE 2014/2059 PREMESSA L’ATI di Catania, nell’ambito delle proprie attività istituzionali, deve procedere alla istruttoria dei progetti di adeguamento, o di realizzazione, dei depuratori finalizzati al superamento della procedura d’infrazione comunitaria di cui al Parere Motivato CE 2059/2014, relativa ad agglomerati, ricadenti nell’ATO di Catania, con un carico generato superiore a 2.000 abitanti equivalenti (A.E.). In particolare la procedura riguarda, nell’ATO Catania, i 21 comuni di Calatabiano, Castel di Iudica, Castiglione di Sicilia, Grammichele, Licodia Eubea, Linguaglossa, Maletto, Maniace, Mazzarrone, Milo, Militello in Val di Catania, Mirabella Imbaccari, Motta S. Anastasia, Piedimonte Etneo, Raddusa, Rammacca, Randazzo, S. Maria di Licodia, S. Michele di Ganzaria, S. Cono, Vizzini. Il Dipartimento Regionale dell’Acqua e dei Rifiuti, il Consorzio d’Ambito in Liquidazione e quest’ATI hanno reiteratamente chiesto ai Comuni la produzione dei progetti necessari al superamento della procedura d’infrazione e dell’emergenza ambientale connessa al mancato collettamento e depurazione dei reflui urbani. Con il D.L.n.32 del 18.04.2019, convertito con modificazioni con la legge n.55 del 2019, c.d. “Sblocca Cantirei” all’Art. 4 – septies è stata prevista l’attribuzione al Commissario Unico per la Depurazione dei compiti di coordinamento per la realizzazione degli interventi funzionali a garantire l’adeguamento, nel minor tempo possibile, alla normativa dell’Unione europea e superare le procedure di infrazione in corso n.