James Douglas Keeps the Peace on Vancouver Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENTS Journal of Occurrences at Nisqually House, 1833

DOCUMENTS Journal of Occurrences at Nisqually House, 1833 INTRODUCTION F art Nisqually was the first permanent settlement of white men on Puget Sound. Fort Vancouver had been headquarters since 1825 and Fort Langley was founded near the mouth of the Fraser river in 1827. Fort N isqually was, therefore, a station which served to link these two together. While the primary object of the Hudson's Bay Company was to collect furs, nevertheless, the great needs of their own trappers, and the needs of Russian America (Alaska), and the Hawaiian Islands and other places for foodstuffs, caused that Company to seriously think of entering into an agricultural form of enterprise. But certain of the directors were not in favor of having the Company branch out into other lines, so a subsidiary company, the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, was formed in 1838 for the purpose of taking advantage of the agri cultural opportunities of the Pacific. This company was financed and officered by members of the Hudson's Bay Company. From that time Fort Nisqually became more an agricultural enterprise than a fur-trad ing post. The Treaty of 1846, by which the United States received the sovereignty of the country to the south of the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude, promised the Hudson's Bay Company and the Puget Sound Agricultural Company that their possessions in that section would be respected. The antagonism of incoming settlers who coveted the fine lands aggravated the situation. Dr. William Fraser T olmie, as Super intendent of the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, remained in charge until 1859, when he removed to Victoria, and Edward Huggins, a clerk, was left as custodian at Nisqually. -

The Survey of HMS Egeria, 1904, SHALE 22, Pp.43–44, January 2010

Context: Gabriola, HMS Egeria Citations: Doe, N.A., Charting Gabriola—the survey of HMS Egeria, 1904, SHALE 22, pp.43–44, January 2010. Copyright restrictions: Copyright © 2010: Gabriola Historical & Museum Society. For reproduction permission e-mail: [email protected] Errors and omissions: Reference: Date posted: January 05, 2012. Charting Gabriola —the survey of HMS Egeria, 1904 by Nick Doe Many Gabriolans, and certainly many HMS Egeria was a 940-ton, 4-gun sloop (two residents of Mudge Island, are familiar with 20-pounders and two machine guns) with the 20th-century “petroglyph” down at three square-rigged masts, a funnel, and one Green Wharf. The petroglyph is carved on coal-fired steam-driven propeller. It was the west face of a large sandstone boulder, 160-feet long, had an iron frame sheathed in about 20 metres (75 ft.) from the wharf. It teak and copper, and was built in 1874 at the was used by the surveyors of HMS Egeria naval dockyards at Pembroke, which is at under Commander J.F. Parry in 1904 as a the head of Milford Haven in southwest benchmark for their tidal observations in Wales. Dodd and False Narrows. The line at the top of the arrow was, according to Parry’s notes, taken to be 20 feet 6 inches above the low low-water on ordinary spring tides, and it was this sea level that was used for defining the shoreline around Gabriola and Mudge on his charts. Next to the benchmark, there is an additional carving, in smaller lettering, but in similar style, now almost completely obscured by the trunk of a Douglas-fir tree, which simply says F.O.E. -

British Columbia 1858

Legislative Library of British Columbia Background Paper 2007: 02 / May 2007 British Columbia 1858 Nearly 150 years ago, the land that would become the province of British Columbia was transformed. The year – 1858 – saw the creation of a new colony and the sparking of a gold rush that dramatically increased the local population. Some of the future province’s most famous and notorious early citizens arrived during that year. As historian Jean Barman wrote: in 1858, “the status quo was irrevocably shattered.” Prepared by Emily Yearwood-Lee Reference Librarian Legislative Library of British Columbia LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BACKGROUND PAPERS AND BRIEFS ABOUT THE PAPERS Staff of the Legislative Library prepare background papers and briefs on aspects of provincial history and public policy. All papers can be viewed on the library’s website at http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/ SOURCES All sources cited in the papers are part of the library collection or available on the Internet. The Legislative Library’s collection includes an estimated 300,000 print items, including a large number of BC government documents dating from colonial times to the present. The library also downloads current online BC government documents to its catalogue. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of the Legislative Library or the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. While great care is taken to ensure these papers are accurate and balanced, the Legislative Library is not responsible for errors or omissions. Papers are written using information publicly available at the time of production and the Library cannot take responsibility for the absolute accuracy of those sources. -

~ Coal Mining in Canada: a Historical and Comparative Overview

~ Coal Mining in Canada: A Historical and Comparative Overview Delphin A. Muise Robert G. McIntosh Transformation Series Collection Transformation "Transformation," an occasional paper series pub- La collection Transformation, publication en st~~rie du lished by the Collection and Research Branch of the Musee national des sciences et de la technologic parais- National Museum of Science and Technology, is intended sant irregulierement, a pour but de faire connaitre, le to make current research available as quickly and inex- plus vite possible et au moindre cout, les recherches en pensively as possible. The series presents original cours dans certains secteurs. Elle prend la forme de research on science and technology history and issues monographies ou de recueils de courtes etudes accep- in Canada through refereed monographs or collections tes par un comite d'experts et s'alignant sur le thenne cen- of shorter studies, consistent with the Corporate frame- tral de la Societe, v La transformation du CanadaLo . Elle work, "The Transformation of Canada," and curatorial presente les travaux de recherche originaux en histoire subject priorities in agricultural and forestry, communi- des sciences et de la technologic au Canada et, ques- cations and space, transportation, industry, physical tions connexes realises en fonction des priorites de la sciences and energy. Division de la conservation, dans les secteurs de: l'agri- The Transformation series provides access to research culture et des forets, des communications et de 1'cspace, undertaken by staff curators and researchers for develop- des transports, de 1'industrie, des sciences physiques ment of collections, exhibits and programs. Submissions et de 1'energie . -

The Implications of the Delgamuukw Decision on the Douglas Treaties"

James Douglas meet Delgamuukw "The implications of the Delgamuukw decision on the Douglas Treaties" The latest decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw vs. The Queen, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, has shed new light on aboriginal title and its relationship to treaties. The issue of aboriginal title has been of particular importance in British Columbia. The question of who owns British Columbia has been the topic of dispute since the arrival and settlement by Europeans. Unlike other parts of Canada, few treaties have been negotiated with the majority of First Nations. With the exception of treaty 8 in the extreme northeast corner of the province, the only other treaties are the 14 entered into by James Douglas, dealing with small tracts of land on Vancouver Island. Following these treaties, the Province of British Columbia developed a policy that in effect did not recognize aboriginal title or alternatively assumed that it had been extinguished, resulting in no further treaties being negotiated1. This continued to be the policy until 1990 when British Columbia agreed to enter into the treaty negotiation process, and the B.C. Treaty Commission was developed. The Nisga Treaty is the first treaty to be negotiated since the Douglas Treaties. This paper intends to explore the Douglas Treaties and the implications of the Delgamuukw decision on these. What assistance does Delgamuukw provide in determining what lands are subject to aboriginal title? What aboriginal title lands did the Douglas people give up in the treaty process? What, if any, aboriginal title land has survived the treaty process? 1 Joseph Trutch, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works and Walter Moberly, Assistant Surveyor- General, initiated this policy. -

Fort Nisqually Markers for His History of Washington, Idaho and Montana

Fort Nisqually Markers 239 three thousand pages of manuscript. In Bancroft's bibliography for his History of Washington, Idaho and Montana is found "Morse, (Eldridge) Notes of Hist. and Res, of Wash. Territory 24 vols. ms." Mr. Morse also wrote reams of Indian legends which have disappeared from "the keeping of the last known custodian. His newspaper venture exhausted his savings and during the last years of his life he maintained himself by selling the products from his loved gardens near Snohomish. His son Ed. C. Morse is a mining engineer well known in Alaska and other parts of the Pacific Northwest. Fort Nisqually Markers On June 9, 1928, appropriate ceremonies commemorated the placing of markers at Fort Nisqually, first home of white men on the shores of Puget Sound. The settlement by the Hudson's Bay Company was begun there on May 30, 1833. The property now belongs to E. 1. Du Pont de Nemours & Company which corporation has sought to save and to mark the old buildings. The Washington State Historical Society, deeming this act worthy of public recognition, prepared a program of dedication. The presiding officer was President C. L. Babcock of the Washington State Historical Society. Music was furnished by the Fort Lewis Military Band. The address of welcome was given by Manager F. T. Beers of the Du Pont Powder works and at the request of President Babcock the response to that address was made by State Senator Walter S. Davis. W. P. Bonney, Secretary of the Washington State Historical Society, read from the old Hudson's Bay Company records the first day's entry in the daily journal of Fort Nisqually. -

Backgrounder

BACKGROUNDER New Playground Equipment Program supports 51 B.C. schools School districts in B.C. are receiving funding from a new program to support building new and replacement playgrounds. The following districts have been approved for funding: Rocky Mountain School District (SD 6) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Martin Morigeau Elementary Kootenay Lake School District (SD 8) $90,000 for a standard playground at WE Graham Elementary -Secondary Arrow Lakes School District (SD 10) $90,000 for a standard playground at Lucerne Elementary Secondary Revelstoke School District (SD 19) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Columbia Park Elementary Vernon School District (SD 22) $90,000 for a standard playground at Mission Hill Elementary Central Okanagan School District (SD 23) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Peachland Elementary Cariboo Chilcotin School District (SD 27) $90,000 for a standard playground at Alexis Creek Elementary/ Jr. Secondary Quesnel School District (SD 28) $90,000 for a standard playground at Voyageur Elementary Chilliwack School District (SD 33) $90,000 for a standard playground AD Rundle Middle Abbotsford School District (SD 34) $90,000 for a standard playground at Dormick Park Elementary Langley School District (SD 35) $90,000 for a standard playground at Shortreed Elementary Surrey School District (SD 36) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Janice Churchill Elementary BACKGROUNDER Delta School District (SD 37) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Chalmers Elementary Richmond School District -

A Week at the Fair; Exhibits and Wonders of the World's Columbian

; V "S. T 67>0 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ""'""'"^ T 500.A2R18" '""''''^ "^"fliiiiWi'lLi£S;;S,A,.week..at the fair 3 1924 021 896 307 'RAND, McNALLY & GO'S A WEEK AT THE FAIR ILLUSTRATING THE EXHIBITS AND WONDERS World's Columbian Exposition WITH SPECIAL DESCRIPTIVE ARTICLES Mrs. Potter Palmer, The C6untess of Aberdeen, Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer, Mr. D. H. Burnh^m (Director of Works), Hon. W. E. Curtis, Messrs. Adler & Sullivan, S. S. Beman, W. W. Boyington, Henry Ives Cobb, W, J. Edbrooke, Frank W. Grogan, Miss Sophia G. Havden, Jarvis Hunt, W. L. B. Jenney, Henry Van Brunt, Francis Whitehouse, and other Architects OF State and Foreign Buildings MAPS, PLANS, AND ILLUSTRATIONS CHICAGO Rand, McNally & Company, Publishers 1893 T . sod- EXPLANATION OF REFERENCE MARKS. In the following pages all the buildings and noticeable features of the grounds are indexed in the following manner: The letters and figures following the names of buildings in heavy black type (like this) are placed there to ascertain their exact location on the map which appears in this guide. Take for example Administration Building (N i8): 18 N- -N 18 On each side of the map are the letters of the alphabet reading downward; and along the margin, top and bottom, are figures reading and increasing from i, on the left, to 27, on the right; N 18, therefore, implies that the Administration Building will be found at that point on the map where lines, if drawn from N to N east and west and from 18 to 18 north and south, would cross each other at right angles. -

Interpretation and Conclusions

"LIKE NUGGETS FROM A GOLD MINEu SEARCHING FOR BRICKS AND THEIR MAKERS IN 'THE OREGON COUNTRY' B~f' Kmtm (1 COfwer~ ;\ th¢...i, ...uhmineJ Ilt SOIl(mla Slale UFU vcr,il y 11'1 partial fulfiUlT'Ietlt of the fCqlJln:mcntfi for the dcgr~ of MASTER OF ARTS tn Copyright 2011 by Kristin O. Converse ii AUTHORlZAnON FOR REPRODUCnON OF MASTER'S THESISIPROJECT 1pM' pernlt"j(m I~ n:pnll.lm.:til.m of Ihi$ rhais in ib endrel)" \Ii' !tbout runt\er uuthorilAtlOO fn.)m me. on the condiHt)Jllhat the per",)f1 Of a,eocy rl;!'(lucMing reproduction the "'OS$. and 1:Jf't)vi~ proper ackruJwkd,rnem nf auth.:If'l'htp. III “LIKE NUGGETS FROM A GOLD MINE” SEARCHING FOR BRICKS AND THEIR MAKERS IN „THE OREGON COUNTRY‟ Thesis by Kristin O. Converse ABSTRACT Purpose of the Study: The history of the Pacific Northwest has favored large, extractive and national industries such as the fur trade, mining, lumbering, fishing and farming over smaller pioneer enterprises. This multi-disciplinary study attempts to address that oversight by focusing on the early brickmakers in „the Oregon Country‟. Using a combination of archaeometry and historical research, this study attempts to make use of a humble and under- appreciated artifact – brick – to flesh out the forgotten details of the emergence of the brick industry, its role in the shifting local economy, as well as its producers and their economic strategies. Procedure: Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis was performed on 89 red, common bricks archaeologically recovered from Fort Vancouver and 113 comparative samples in an attempt to „source‟ the brick. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A. -

HBCA Biographical Sheet

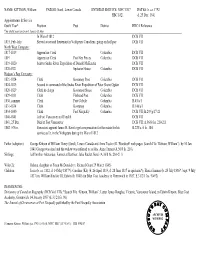

NAME: KITTSON, William PARISH: Sorel, Lower Canada ENTERED SERVICE: NWC 1817 DATES: b. ca. 1792 HBC 1821 d. 25 Dec. 1841 Appointments & Service Outfit Year* Position Post District HBCA Reference *An Outfit year ran from 1 June to 31 May In War of 1812 DCB VII 1815, Feb.-July Served as second lieutenant in Voltigeurs Canadiens, going on half-pay DCB VII North West Company: 1817-1819 Apprentice Clerk Columbia DCB VII 1819 Apprentice Clerk Fort Nez Perces Columbia DCB VII 1819-1820 Sent to Snake River Expedition of Donald McKenzie DCB VII 1820-1821 Spokane House Columbia DCB VII Hudson’s Bay Company: 1821-1824 Clerk Kootenay Post Columbia DCB VII 1824-1825 Second in command of the Snake River Expedition of Peter Skene Ogden DCB VII 1826-1829 Clerk in charge Kootenae House Columbia DCB VII 1829-1831 Clerk Flathead Post Columbia DCB VII 1830, summer Clerk Fort Colvile Columbia B.45/a/1 1831-1834 Clerk Kootenay Columbia B.146/a/1 1834-1840 Clerk Fort Nisqually Columbia DCB VII; B.239/g/17-21 1840-1841 At Fort Vancouver in ill health DCB VII 1841, 25 Dec. Died at Fort Vancouver DCB VII; A.36/8 fos. 210-211 1842, 5 Nov. Executors appoint James H. Kerr to get compensation for the estate for his B.223/z /4 fo. 184 service as Lt. in the Voltigeurs during the War of 1812 Father (adoptive): George Kittson of William Henry (Sorel), Lower Canada and Anne Tucker (R. Woodruff web pages; Search File “Kittson, William”); by 10 Jan. -

A British Perspective on the War of 1812 by Andrew Lambert

A British Perspective on the War of 1812 by Andrew Lambert The War of 1812 has been referred to as a victorious “Second A decade of American complaints and economic restrictions action. Finally, on January 14th 1815 the American flagship, the rights and impressment. By accepting these terms the Americans War for Independence,” and used to define Canadian identity, only served to convince the British that Jefferson and Madison big 44 gun frigate USS President commanded by Stephen Decatur, acknowledged the complete failure of the war to achieve any of but the British only remember 1812 as the year Napoleon were pro-French, and violently anti-British. Consequently, was hunted down and defeated off Sandy Hook by HMS their strategic or political aims. Once the treaty had been marched to Moscow. This is not surprising. In British eyes, when America finally declared war, she had very few friends Endymion. The American flagship became signed, on Christmas Eve 1814, the the conflict with America was an annoying sideshow. The in Britain. Many remembered the War of Independence, some HMS President, a name that still graces the list British returned the focus to Europe. Americans had stabbed them in the back while they, the had lost fathers or brothers in the fighting; others were the of Her Majesty’s Fleet. The war at sea had British, were busy fighting a total war against the French sons of Loyalists driven from their homes. turned against America, the U.S. Navy had The wisdom of their decision soon Empire, directed by their most inveterate enemy.