The Implications of the Delgamuukw Decision on the Douglas Treaties"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 71 (2015) Article 5 Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Borrows, John. "Aboriginal Title and Private Property." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 71. (2015). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol71/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows* Q: What did Indigenous Peoples call this land before Europeans arrived? A: “OURS.”1 I. INTRODUCTION In the ground-breaking case of Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia2 the Supreme Court of Canada recognized and affirmed Aboriginal title under section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.3 It held that the Tsilhqot’in Nation possess constitutionally protected rights to certain lands in central British Columbia.4 In drawing this conclusion the Tsilhqot’in secured a declaration of “ownership rights similar to those associated with fee simple, including: the right to decide how the land will be used; the right of enjoyment and occupancy of the land; the right to possess the land; the right to the economic benefits of the land; and the right to pro-actively use and manage the land”.5 These are wide-ranging rights. -

KI LAW of INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law Of

KI LAW OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law of indigenous peoples Class here works on the law of indigenous peoples in general For law of indigenous peoples in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, see KIA20.2-KIA8900.2 For law of ancient peoples or societies, see KL701-KL2215 For law of indigenous peoples of India (Indic peoples), see KNS350-KNS439 For law of indigenous peoples of Africa, see KQ2010-KQ9000 For law of Aboriginal Australians, see KU350-KU399 For law of indigenous peoples of New Zealand, see KUQ350- KUQ369 For law of indigenous peoples in the Americas, see KIA-KIX Bibliography 1 General bibliography 2.A-Z Guides to law collections. Indigenous law gateways (Portals). Web directories. By name, A-Z 2.I53 Indigenous Law Portal. Law Library of Congress 2.N38 NativeWeb: Indigenous Peoples' Law and Legal Issues 3 Encyclopedias. Law dictionaries For encyclopedias and law dictionaries relating to a particular indigenous group, see the group Official gazettes and other media for official information For departmental/administrative gazettes, see the issuing department or administrative unit of the appropriate jurisdiction 6.A-Z Inter-governmental congresses and conferences. By name, A- Z Including intergovernmental congresses and conferences between indigenous governments or those between indigenous governments and federal, provincial, or state governments 8 International intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) 10-12 Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) Inter-regional indigenous organizations Class here organizations identifying, defining, and representing the legal rights and interests of indigenous peoples 15 General. Collective Individual. By name 18 International Indian Treaty Council 20.A-Z Inter-regional councils. By name, A-Z Indigenous laws and treaties 24 Collections. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

The Native Land Policies of Governor James Douglas

The Native Land Policies of Governor James Douglas Cole Harris* n British Columbia, as in other settler colonies, it was in the interest of capital, labour, and settlers to obtain unimpeded access to Iland. The power to do so lay in the state’s military apparatus and in an array of competences that enabled it to manage people and distance. Justification for the dispossession of Native peoples was provided by assumptions about the benefits of civilizing savages and of turning wasteful land uses into productive ones. Colonization depended on this combination of interest, power, and cultural judgment. In British Columbia, approximately a third of 1 percent of the land of the province was set aside in Native reserves. The first of these reserves were laid out on Vancouver Island in the 1850s, and the last, to all intents and purposes, during the First World War. Not all government officials thought them sufficient, and during these years there were two sustained attempts to provide larger Native reserves. The first, in the early 1860s, was associated with Governor James Douglas, and the second, in the late 1870s, with Gilbert Malcolm Sproat, an Indian reserve commis- sioner who knew Douglas and admired and emulated his Native land policies. Both attempts, however, were quickly superseded. Douglas resigned in April 1864. His Native land policies were discontinued and some of his reserves were reduced. Sproat resigned in March 1880, and over the next almost twenty years his successor, Peter O’Reilly, allocated the small reserves that the government and settler opinion demanded. The provincial government, which by the 1880s controlled provincial * Editors' note: This is a necessarily verbatim version of Cole Harris's deposition as an expert witness in a forthcoming land claims case. -

Building of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails Researched and Written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, June 2010; Updated Dec 2012 and Dec 2013

Early Trail Building in the New Colony of British Columbia — John Hall’s Building of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails Researched and written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, June 2010; updated Dec 2012 and Dec 2013. A recent “find” of colonial correspondence in the British Columbia Archives tells a story about the construction of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails between 1862 and 1864 by pioneer settler John Hall. (In 1870 Hall pre-empted 160 acres of Crown Land on Indian Arm and became Belcarra’s first European settler.) The correspondence involves a veritable “who’s who” of people in the administration in the young ‘Colony of British Columbia’. This historic account serves to highlight one of the many challenges faced by our pioneers during the period of colonial settlement in British Columbia. Sir James Douglas When the Fraser River Gold Rush began in the spring of 1858, there were only about 250 to 300 Europeans living in the Fraser Valley. The gold rush brought on the order of 30,000 miners flocking to the area in the quest for riches, many of whom came north from the California gold fields. As a result, the British Colonial office declared a new Crown colony on the mainland called ‘British Columbia’ and appointed Sir James Douglas as the first Governor. (1) The colony was first proclaimed at Fort Langley on 19th November, 1858, but in early 1859 the capital was moved to the planned settlement called ‘New Westminster’, Sir James Douglas strategically located on the northern banks of the Fraser River. -

Claim of Aboriginal Ownership Chief David Latasse Was Present At

#6 Sources on the Douglas Treaties Douglas Treaties Document #1: Claim of Aboriginal Ownership Chief David Latasse was present at the treaty negotiations in Victoria in 1850. His recollections were recorded in 1934 when he was reportedly 105 years old: For some time after the whites commenced building their settlement they ferried their supplies ashore. Then they desired to build a dock, where ships could be tied up close to shore. Explorers found suitable timbers could be obtained at Cordova Bay, and a gang of whites, Frenchmen and Kanakas [Hawaiians] were sent there to cut piles. The first thing they did was set a fire which nearly got out of hand, making such smoke as to attract attention of the Indians for forty miles around. Chief Hotutstun of Salt Spring sent messengers to chief Whutsaymullet of the Saanich tribes, telling him that the white men were destroying his heritage and would frighten away fur and game animals. They met and jointly manned two big canoes and came down the coast to see what damage was being done and to demand pay from Douglas. Hotutstun was interested by the prospect of sharing in any gifts made to Whutsaymullet but also, indirectly, as the Chief Paramount of all the Indians of Saanich. As the two canoes rounded the point and paddled into Cordova Bay they were seen by camp cooks of the logging party, who became panic stricken. Rushing into the woods they yelled the alarm of Indians on the warpath. Every Frenchman and Kanaka dropped his tool and took to his heels, fleeing through the woods to Victoria. -

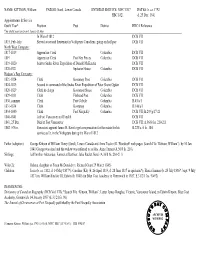

HBCA Biographical Sheet

NAME: KITTSON, William PARISH: Sorel, Lower Canada ENTERED SERVICE: NWC 1817 DATES: b. ca. 1792 HBC 1821 d. 25 Dec. 1841 Appointments & Service Outfit Year* Position Post District HBCA Reference *An Outfit year ran from 1 June to 31 May In War of 1812 DCB VII 1815, Feb.-July Served as second lieutenant in Voltigeurs Canadiens, going on half-pay DCB VII North West Company: 1817-1819 Apprentice Clerk Columbia DCB VII 1819 Apprentice Clerk Fort Nez Perces Columbia DCB VII 1819-1820 Sent to Snake River Expedition of Donald McKenzie DCB VII 1820-1821 Spokane House Columbia DCB VII Hudson’s Bay Company: 1821-1824 Clerk Kootenay Post Columbia DCB VII 1824-1825 Second in command of the Snake River Expedition of Peter Skene Ogden DCB VII 1826-1829 Clerk in charge Kootenae House Columbia DCB VII 1829-1831 Clerk Flathead Post Columbia DCB VII 1830, summer Clerk Fort Colvile Columbia B.45/a/1 1831-1834 Clerk Kootenay Columbia B.146/a/1 1834-1840 Clerk Fort Nisqually Columbia DCB VII; B.239/g/17-21 1840-1841 At Fort Vancouver in ill health DCB VII 1841, 25 Dec. Died at Fort Vancouver DCB VII; A.36/8 fos. 210-211 1842, 5 Nov. Executors appoint James H. Kerr to get compensation for the estate for his B.223/z /4 fo. 184 service as Lt. in the Voltigeurs during the War of 1812 Father (adoptive): George Kittson of William Henry (Sorel), Lower Canada and Anne Tucker (R. Woodruff web pages; Search File “Kittson, William”); by 10 Jan. -

Drawing of Colonial Victoria “Victoria, on Vancouver Island.” Artist: Linton (Ca. 1857). (BC Archives, Call No. G-03249)

��� ����������������������������� � � � ������������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������� ������������������������������������ � � � � ��� ������������������������ � �������������������������������������������������������������� � � ���������������������� ������������������ � �������������� ������������� ��������������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������� ����������������� ����������� � ��������������������������������� � ��������� ����������� ���������������������� ����������������������� �� ����������� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � ��� ������������������������������ � ����������� ���������������������� ����������������������� ����������� ��������� ������������������������������� ������������������������������ ���������� ������ ������������������������� ��������������� ������������������������ ������������ ��������� ����������������������������� �������������������������� �������� ������������������������������ ������������������������������� �������������������������������� ������������ ���������� ���������������������������� ������������������������������ ������������������������������� ��������������������������������� ���������������������� ���������������������������� ������������ ���������������������� ���������������������������������� ��������������������������� ������������������������������� ��������������� ������������������������������ ����������������������������� ����������� �������������������������� ������������������������ -

HISTORY Discover Your Legislature Series

HISTORY Discover Your Legislature Series Legislative Assembly of British Columbia Victoria British Columbia V8V 1X4 CONTENTS UP TO 1858 1 1843 – Fort Victoria is Established 1 1846 – 49th Parallel Becomes International Boundary 1 1849 – Vancouver Island Becomes a Colony 1 1850 – First Aboriginal Land Treaties Signed 2 1856 – First House of Assembly Elected 2 1858 – Crown Colony of B.C. on the Mainland is Created 3 1859-1870 3 1859 – Construction of “Birdcages” Started 3 1863 – Mainland’s First Legislative Council Appointed 4 1866 – Island and Mainland Colonies United 4 1867 – Dominion of Canada Created, July 1 5 1868 – Victoria Named Capital City 5 1871-1899 6 1871 – B.C. Joins Confederation 6 1871 – First Legislative Assembly Elected 6 1872 – First Public School System Established 7 1874 – Aboriginals and Chinese Excluded from the Vote 7 1876 – Property Qualification for Voting Dropped 7 1886 – First Transcontinental Train Arrives in Vancouver 8 1888 – B.C.’s First Health Act Legislated 8 1893 – Construction of Parliament Buildings started 8 1895 – Japanese Are Disenfranchised 8 1897 – New Parliament Buildings Completed 9 1898 – A Period of Political Instability 9 1900-1917 10 1903 – First B.C Provincial Election Involving Political Parties 10 1914 – The Great War Begins in Europe 10 1915 – Parliament Building Additions Completed 10 1917 – Women Win the Right to Vote 11 1917 – Prohibition Begins by Referendum 11 CONTENTS (cont'd) 1918-1945 12 1918 – Mary Ellen Smith, B.C.’s First Woman MLA 12 1921 – B.C. Government Liquor Stores Open 12 1920 – B.C.’s First Social Assistance Legislation Passed 12 1923 – Federal Government Prohibits Chinese Immigration 13 1929 – Stock Market Crash Causes Great Depression 13 1934 – Special Powers Act Imposed 13 1934 – First Minimum Wage Enacted 14 1938 – Unemployment Leads to Unrest 14 1939 – World War II Declared, Great Depression Ends 15 1941 – B.C. -

Much Ado About Dittos: Wewaykum and the Fiduciary Obligation of the Crown

Much Ado About Dittos: Wewaykum and the Fiduciary Obligation of the Crown David E. Elliott * The Crown's special fiduciary obligation to Canadian aboriginal peoples has offered a pliant tool for aboriginal redress against the state. The duty has two related but distinct forms, a common law form based on the Supreme Court of Canada's 1984 decision in Guerin v. R. and a constitutional form based on the Court's 1990 decision in R. v. Sparrow, The constitutional form is grounded in section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982, and was incorporated into the Court's guidelines on section 35(1) justification, but the Guerin form remained more obscure. The Court has applied the Guerin duty flexibly, but has paid less attention to clarifying its scope, content and consequences. It has been unclear just what interests that duty protects, and what level and form of protection it requires. The duty is an exception to the general proposition that the Crown should be free from fiduciary duties because of its broader public obligations. In Guerin, the Court justified the exception on the basis of the "unique v independent character of aboriginal title, However, for aboriginal interests derived from aboriginal title, the Court failed to say how much independence was needed. Moreover, after Guerin, the Court tended to neglect that issue and other outer parameters of the duty. One result was a flood of Guerin·type fiduciary cases in the lower courts. In Wewaykum Indian Band v. Canada, aboriginal resettlement and competition for land, and a bizarre bureaucratic blunder, brought one of those cases to the Supreme Court, giving the Court an opportunity to address the uncertainties.