Patricia Vaughan, 1978

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Columbia 1858

Legislative Library of British Columbia Background Paper 2007: 02 / May 2007 British Columbia 1858 Nearly 150 years ago, the land that would become the province of British Columbia was transformed. The year – 1858 – saw the creation of a new colony and the sparking of a gold rush that dramatically increased the local population. Some of the future province’s most famous and notorious early citizens arrived during that year. As historian Jean Barman wrote: in 1858, “the status quo was irrevocably shattered.” Prepared by Emily Yearwood-Lee Reference Librarian Legislative Library of British Columbia LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BACKGROUND PAPERS AND BRIEFS ABOUT THE PAPERS Staff of the Legislative Library prepare background papers and briefs on aspects of provincial history and public policy. All papers can be viewed on the library’s website at http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/ SOURCES All sources cited in the papers are part of the library collection or available on the Internet. The Legislative Library’s collection includes an estimated 300,000 print items, including a large number of BC government documents dating from colonial times to the present. The library also downloads current online BC government documents to its catalogue. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of the Legislative Library or the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. While great care is taken to ensure these papers are accurate and balanced, the Legislative Library is not responsible for errors or omissions. Papers are written using information publicly available at the time of production and the Library cannot take responsibility for the absolute accuracy of those sources. -

~ Coal Mining in Canada: a Historical and Comparative Overview

~ Coal Mining in Canada: A Historical and Comparative Overview Delphin A. Muise Robert G. McIntosh Transformation Series Collection Transformation "Transformation," an occasional paper series pub- La collection Transformation, publication en st~~rie du lished by the Collection and Research Branch of the Musee national des sciences et de la technologic parais- National Museum of Science and Technology, is intended sant irregulierement, a pour but de faire connaitre, le to make current research available as quickly and inex- plus vite possible et au moindre cout, les recherches en pensively as possible. The series presents original cours dans certains secteurs. Elle prend la forme de research on science and technology history and issues monographies ou de recueils de courtes etudes accep- in Canada through refereed monographs or collections tes par un comite d'experts et s'alignant sur le thenne cen- of shorter studies, consistent with the Corporate frame- tral de la Societe, v La transformation du CanadaLo . Elle work, "The Transformation of Canada," and curatorial presente les travaux de recherche originaux en histoire subject priorities in agricultural and forestry, communi- des sciences et de la technologic au Canada et, ques- cations and space, transportation, industry, physical tions connexes realises en fonction des priorites de la sciences and energy. Division de la conservation, dans les secteurs de: l'agri- The Transformation series provides access to research culture et des forets, des communications et de 1'cspace, undertaken by staff curators and researchers for develop- des transports, de 1'industrie, des sciences physiques ment of collections, exhibits and programs. Submissions et de 1'energie . -

The Implications of the Delgamuukw Decision on the Douglas Treaties"

James Douglas meet Delgamuukw "The implications of the Delgamuukw decision on the Douglas Treaties" The latest decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw vs. The Queen, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, has shed new light on aboriginal title and its relationship to treaties. The issue of aboriginal title has been of particular importance in British Columbia. The question of who owns British Columbia has been the topic of dispute since the arrival and settlement by Europeans. Unlike other parts of Canada, few treaties have been negotiated with the majority of First Nations. With the exception of treaty 8 in the extreme northeast corner of the province, the only other treaties are the 14 entered into by James Douglas, dealing with small tracts of land on Vancouver Island. Following these treaties, the Province of British Columbia developed a policy that in effect did not recognize aboriginal title or alternatively assumed that it had been extinguished, resulting in no further treaties being negotiated1. This continued to be the policy until 1990 when British Columbia agreed to enter into the treaty negotiation process, and the B.C. Treaty Commission was developed. The Nisga Treaty is the first treaty to be negotiated since the Douglas Treaties. This paper intends to explore the Douglas Treaties and the implications of the Delgamuukw decision on these. What assistance does Delgamuukw provide in determining what lands are subject to aboriginal title? What aboriginal title lands did the Douglas people give up in the treaty process? What, if any, aboriginal title land has survived the treaty process? 1 Joseph Trutch, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works and Walter Moberly, Assistant Surveyor- General, initiated this policy. -

Claim of Aboriginal Ownership Chief David Latasse Was Present At

#6 Sources on the Douglas Treaties Douglas Treaties Document #1: Claim of Aboriginal Ownership Chief David Latasse was present at the treaty negotiations in Victoria in 1850. His recollections were recorded in 1934 when he was reportedly 105 years old: For some time after the whites commenced building their settlement they ferried their supplies ashore. Then they desired to build a dock, where ships could be tied up close to shore. Explorers found suitable timbers could be obtained at Cordova Bay, and a gang of whites, Frenchmen and Kanakas [Hawaiians] were sent there to cut piles. The first thing they did was set a fire which nearly got out of hand, making such smoke as to attract attention of the Indians for forty miles around. Chief Hotutstun of Salt Spring sent messengers to chief Whutsaymullet of the Saanich tribes, telling him that the white men were destroying his heritage and would frighten away fur and game animals. They met and jointly manned two big canoes and came down the coast to see what damage was being done and to demand pay from Douglas. Hotutstun was interested by the prospect of sharing in any gifts made to Whutsaymullet but also, indirectly, as the Chief Paramount of all the Indians of Saanich. As the two canoes rounded the point and paddled into Cordova Bay they were seen by camp cooks of the logging party, who became panic stricken. Rushing into the woods they yelled the alarm of Indians on the warpath. Every Frenchman and Kanaka dropped his tool and took to his heels, fleeing through the woods to Victoria. -

Backgrounder

BACKGROUNDER New Playground Equipment Program supports 51 B.C. schools School districts in B.C. are receiving funding from a new program to support building new and replacement playgrounds. The following districts have been approved for funding: Rocky Mountain School District (SD 6) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Martin Morigeau Elementary Kootenay Lake School District (SD 8) $90,000 for a standard playground at WE Graham Elementary -Secondary Arrow Lakes School District (SD 10) $90,000 for a standard playground at Lucerne Elementary Secondary Revelstoke School District (SD 19) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Columbia Park Elementary Vernon School District (SD 22) $90,000 for a standard playground at Mission Hill Elementary Central Okanagan School District (SD 23) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Peachland Elementary Cariboo Chilcotin School District (SD 27) $90,000 for a standard playground at Alexis Creek Elementary/ Jr. Secondary Quesnel School District (SD 28) $90,000 for a standard playground at Voyageur Elementary Chilliwack School District (SD 33) $90,000 for a standard playground AD Rundle Middle Abbotsford School District (SD 34) $90,000 for a standard playground at Dormick Park Elementary Langley School District (SD 35) $90,000 for a standard playground at Shortreed Elementary Surrey School District (SD 36) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Janice Churchill Elementary BACKGROUNDER Delta School District (SD 37) $105,000 for an accessible playground at Chalmers Elementary Richmond School District -

A Week at the Fair; Exhibits and Wonders of the World's Columbian

; V "S. T 67>0 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ""'""'"^ T 500.A2R18" '""''''^ "^"fliiiiWi'lLi£S;;S,A,.week..at the fair 3 1924 021 896 307 'RAND, McNALLY & GO'S A WEEK AT THE FAIR ILLUSTRATING THE EXHIBITS AND WONDERS World's Columbian Exposition WITH SPECIAL DESCRIPTIVE ARTICLES Mrs. Potter Palmer, The C6untess of Aberdeen, Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer, Mr. D. H. Burnh^m (Director of Works), Hon. W. E. Curtis, Messrs. Adler & Sullivan, S. S. Beman, W. W. Boyington, Henry Ives Cobb, W, J. Edbrooke, Frank W. Grogan, Miss Sophia G. Havden, Jarvis Hunt, W. L. B. Jenney, Henry Van Brunt, Francis Whitehouse, and other Architects OF State and Foreign Buildings MAPS, PLANS, AND ILLUSTRATIONS CHICAGO Rand, McNally & Company, Publishers 1893 T . sod- EXPLANATION OF REFERENCE MARKS. In the following pages all the buildings and noticeable features of the grounds are indexed in the following manner: The letters and figures following the names of buildings in heavy black type (like this) are placed there to ascertain their exact location on the map which appears in this guide. Take for example Administration Building (N i8): 18 N- -N 18 On each side of the map are the letters of the alphabet reading downward; and along the margin, top and bottom, are figures reading and increasing from i, on the left, to 27, on the right; N 18, therefore, implies that the Administration Building will be found at that point on the map where lines, if drawn from N to N east and west and from 18 to 18 north and south, would cross each other at right angles. -

Barbara Stannard for the Coal Tyee Project II, on May 17, 1983 at Nanaimo ~- Centennial Museum

This ~Barbara Stannard for the Coal Tyee Project II, on May 17, 1983 at Nanaimo ~- Centennial Museum. LB: Mrs. Stannard is the President of the Board of Directors of the Museum . She is a past president of the Nanaimo Historical Society and she is just finishing up her term as President of the B.C. Historical Society ... No? BS: One more year. LB: Oh, excuse me. She is half way through her term as President of the B.C. Historical Society. Mrs. Stannard's family, both sides of the family, BS: That is association. LB: Mrs . Stannard I think we will try to trace your family's background and coming to Nanaimo starting with the earliest ones we can and working up to the present. So,you had ancestors on the Princess Royal or on the Harpooner? BS: On the Harpooner, before the Princess Royal. LB: Before the Princess Royal. Can you tell me who that was. BS: The Muirs and McGregors. They were related to my mother's family, the Campbells through marriage and there were two of the Campbell brothers that came out just after the Muirs and McGregors and went up to Rupert and then left, or went up to Fort Rupert, then left and went on to Alaska . LB: They were on the Harpooner? BS: The Muirs and McGregors were, yes . LB: Oh, all right. When did the Campbells ... BS: The Campbells came out, and I don't know what boat they came out on, but they came across the United States to San Francisco and then sailed up to Victoria and then took Indian canoe from there to Fort Rupert~ where they stayed a short time. -

Boas, Hunt, and the Ethnographic Silencing of First Nations Women

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Anthropology Papers Department of Anthropology 2014 My Sisters Will Not Speak: Boas, Hunt, and the Ethnographic Silencing of First Nations Women Margaret Bruchac University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Bruchac, M. (2014). My Sisters Will Not Speak: Boas, Hunt, and the Ethnographic Silencing of First Nations Women. Curator: The Museum Journal, 57 (2), 153-171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12058 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/170 For more information, please contact [email protected]. My Sisters Will Not Speak: Boas, Hunt, and the Ethnographic Silencing of First Nations Women Abstract First Nations women were instrumental to the collection of Northwest Coast Indigenous culture, yet their voices are nearly invisible in the published record. The contributions of George Hunt, the Tlingit/British culture broker who collaborated with anthropologist Franz Boas, overshadow the intellectual influence of his mother, Anislaga Mary Ebbetts, his sisters, and particularly his Kwakwaka'wakw wives, Lucy Homikanis and Tsukwani Francine. In his correspondence with Boas, Hunt admitted his dependence upon high-status Indigenous women, and he gave his female relatives visual prominence in film, photographs, and staged performances, but their voices are largely absent from anthropological texts. Hunt faced many unexpected challenges (disease, death, arrest, financial hardship, and the suspicions of his neighbors), yet he consistently placed Boas' demands, perspectives, and editorial choices foremost. -

VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, and COLONIALISM on the NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA a THESIS Pres

“OUR PEOPLE SCATTERED:” VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, AND COLONIALISM ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA A THESIS Presented to the University of Oregon History Department and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ian S. Urrea Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the History Department by: Jeffrey Ostler Chairperson Ryan Jones Member Brett Rushforth Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2019 ii © 2019 Ian S. Urrea iii THESIS ABSTRACT Ian S. Urrea Master of Arts University of Oregon History Department September 2019 Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846” This thesis interrogates the practice, economy, and sociopolitics of slavery and captivity among Indigenous peoples and Euro-American colonizers on the Northwest Coast of North America from 1774-1846. Through the use of secondary and primary source materials, including the private journals of fur traders, oral histories, and anthropological analyses, this project has found that with the advent of the maritime fur trade and its subsequent evolution into a land-based fur trading economy, prolonged interactions between Euro-American agents and Indigenous peoples fundamentally altered the economy and practice of Native slavery on the Northwest Coast. -

26Oi CONTRIBUTIONS to the HISTORY of the PACIFIC

26oi CONTRIBUTIONS to the HISTORY of the PACIFIC NORTHWEST THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY W. D. VINCENT CONTRIBUTIONS to the HISTORY of the PACIFIC NORTHWEST THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY W. D. VINCENT Spokane Studj? Club Series PUBLISHED BY THE STATE COLLEGE OF WASHINGTON 1927 PREFATORY STATEMENT By E. A. BRYAN T«HE successful business man who is endowed with historical sense and a passion for research has a unique opportunity, not possessed by the recluse, of contributing to regional history. The wide range of the business man's contacts, possessed as he is of the means for col lecting and preserving rare books, manuscripts and illus trative material, and even of travel throughout the region for the verification and classification of historical data, enables him to give a broad, accurate, and common sense interpretation to the history of the men and things of an earlier day. Mr. Vincent has for many years been a student of Northwestern history and has been a collector of its source material and an intelligent expositor of its earlier phases. From time to time he has given to his fellow members of the Spokane Study Club the results of his studies. This paper on the Hudson's Bay Company is one of five such papers read to the club which the State College of Washington will publish as series A, of "Con tributions to the History of the Northwest." THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY By W. D. VINCENT 1 HAVE been an adventurer. When I undertook the venture of preparing this paper on the "Great Company" I did not know the perils and pleasures into which my reading would carry me. -

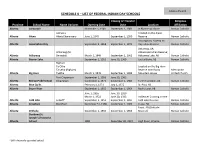

Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools

SCHEDULE K – LIST OF FEDERAL INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS Closing or Transfer Religious Province School Name Name Variants Opening Date Date Location Affiliation Alberta Alexander November 1, 1949 September 1, 1981 In Riviere qui Barre Roman Catholic Glenevis Located on the Alexis Alberta Alexis Alexis Elementary June 1, 1949 September 1, 1990 Reserve Roman Catholic Assumption, Alberta on Alberta Assumption Day September 9, 1968 September 1, 1971 Hay Lakes Reserve Roman Catholic Atikameg, AB; Atikameg (St. Atikamisie Indian Reserve; Alberta Atikameg Benedict) March 1, 1949 September 1, 1962 Atikameg Lake, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Beaver Lake September 1, 1952 June 30, 1960 Lac La Biche, AB Roman Catholic Bighorn Ta Otha Located on the Big Horn Ta Otha (Bighorn) Reserve near Rocky Mennonite Alberta Big Horn Taotha March 1, 1949 September 1, 1989 Mountain House United Church Fort Chipewyan September 1, 1956 June 30, 1963 Alberta Bishop Piché School Chipewyan September 1, 1971 September 1, 1985 Fort Chipewyan, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Blue Quills February 1, 1971 July 1, 1972 St. Paul, AB Alberta Boyer River September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Rocky Lane, AB Roman Catholic June 1, 1916 June 30, 1920 March 1, 1922 June 30, 1933 At Beaver Crossing on the Alberta Cold Lake LeGoff1 September 1, 1953 September 1, 1997 Cold Lake Reserve Roman Catholic Alberta Crowfoot Blackfoot December 31, 1968 September 1, 1989 Cluny, AB Roman Catholic Faust, AB (Driftpile Alberta Driftpile September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Reserve) Roman Catholic Dunbow (St. Joseph’s) Industrial Alberta School 1884 December 30, 1922 High River, Alberta Roman Catholic 1 Still a federally-operated school. -

Background to the Douglas Treaties in the 1840S, Vancouver Island Was Home to Thousands of First Nations People Belonging to Nu

#1 Background to the Douglas Treaties In the 1840s, Vancouver Island was home to thousands of First Nations people belonging to Nuuchah’nulth, Coast Salish, and Kwakwaka’wakw speaking groups (an 1856 census counted 33,873 Indigenous people on Vancouver Island).1 In 1843, the Hudson’s Bay fur trading company established a trading post at Fort Victoria in the territory of the Lekwungen Coast Salish-speaking people. By 1846, Britain and the United States agreed to divide the territories west of the Rocky Mountains, so that the United States controlled the area south of the 49th parallel and Britain controlled the area north of this border, including Vancouver Island. To maintain its hold on this territory and have continued access to the Pacific Ocean for trade routes, the British Colonial Office created a colony on Vancouver Island in 1849. Colonial powers like Britain believed that if they could settle enough of their own citizens permanently in Indigenous territories, they could claim these territories as their own. Britain allowed the Hudson’s Bay Company to manage the Colony of Vancouver Island and agreed to let the company have exclusive trading rights for the next ten years. In exchange, the company agreed to colonize the island with British settlers. Before the Hudson’s Bay Company could sell the land to the settlers, it first had to purchase the land from its original owners, the Indigenous people. This was described as “extinguishing” or ending Aboriginal rights to land. Colonial powers usually purchased land from Indigenous people by negotiating treaties. Between 1850 and 1854, James Douglas signed treaties with fourteen Aboriginal communities on Vancouver Island.