Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus on Congregation Emanu-El the SCRIBE

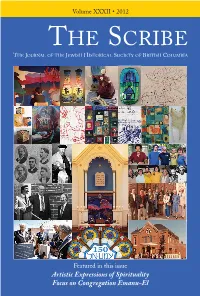

Volume XXXII • 2012 THE SCRIBE THE JOURNAL OF THE JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Featured in this issue Artistic Expressions of Spirituality Focus on Congregation Emanu-El THE SCRIBE THE JOURNAL OF THE JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Artistic Expressions of Spirituality Focus on Congregation Emanu-El Volume XXXII • 2012 This issue of The Scribe has been generously supported by: the Cyril Leonoff Fund for the Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia; the Yosef Wosk Publication Endowment Fund; Dora and Sid Golden and family; Betty and Irv Nitkin; and an anonymous donor. Editor: Cynthia Ramsay Publications Committee: Betty Nitkin, Perry Seidelman and archivist Jennifer Yuhasz, with appreciation to Josie Tonio McCarthy and Marcy Babins Layout: Western Sky Communications Ltd. Statements of fact or opinion appearing in The Scribe are made on the responsibility of the authors alone and do not imply the endorsements of the editor or the Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia. Please address all submissions and communications on editorial and circulation matters to: THE SCRIBE Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia 6184 Ash Street, Vancouver, B.C., V5Z 3G9 604-257-5199 • [email protected] • http://www.jewishmuseum.ca Membership Rates: Households – $54; Institutions/Organizations – $75 Includes one copy of each issue of The Scribe and The Chronicle Back issues and e xtra copies – $20 plus postage ISSN 0824 6048 © The Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia is a nonprofit organization. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted without the written permission of the publisher, with the following exception: JHSBC grants permission to individuals to download or print single copies of articles for personal use. -

Orcadians (And Some Shetlanders) Who Worked West of the Rockies in the Fur Trade up to 1858 (Unedited Biographies in Progress)

Orcadians (and some Shetlanders) who worked west of the Rockies in the fur trade up to 1858 (unedited biographies in progress) As compiled by: Bruce M. Watson 208-1948 Beach Avenue Vancouver, B. C. Canada, V6G 1Z2 As of: March, 1998 Information to be shared with Family History Society of Orkney. Corrections, additions, etc., to be returned to Bruce M. Watson. A complete set of biographies to remain in Orkney with Society. George Aitken [variation: Aiken ] (c.1815-?) [sett-Willamette] HBC employee, British: Orcadian Scot, b. c. August 20, 1815 in "Greenay", Birsay, Orkney, North Britain [U.K.] to Alexander (?-?) and Margaret [Johnston] Aiken (?-?), d. (date and place not traced), associated with: Fort Vancouver general charges (l84l-42) blacksmith Fort Stikine (l842-43) blacksmith steamer Beaver (l843-44) blacksmith Fort Vancouver (l844-45) blacksmith Fort Vancouver Depot (l845-49) blacksmith Columbia (l849-50) Columbia (l850-52) freeman Twenty one year old Orcadian blacksmith, George Aiken, signed on with the Hudson's Bay Company February 27, l836 and sailed to York Factory where he spent outfits 1837-40; he then moved to and worked at Norway House in 1840-41 before being assigned to the Columbia District in 1841. Aiken worked quietly and competently in the Columbia district mainly at coastal forts and on the steamer Beaver as a blacksmith until March 1, 1849 at which point he went to California, most certainly to participate in the Gold Rush. He appears to have returned to settle in the Willamette Valley and had an association with the HBC until 1852. Aiken's family life or subsequent activities have not been traced. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

The Implications of the Delgamuukw Decision on the Douglas Treaties"

James Douglas meet Delgamuukw "The implications of the Delgamuukw decision on the Douglas Treaties" The latest decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw vs. The Queen, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, has shed new light on aboriginal title and its relationship to treaties. The issue of aboriginal title has been of particular importance in British Columbia. The question of who owns British Columbia has been the topic of dispute since the arrival and settlement by Europeans. Unlike other parts of Canada, few treaties have been negotiated with the majority of First Nations. With the exception of treaty 8 in the extreme northeast corner of the province, the only other treaties are the 14 entered into by James Douglas, dealing with small tracts of land on Vancouver Island. Following these treaties, the Province of British Columbia developed a policy that in effect did not recognize aboriginal title or alternatively assumed that it had been extinguished, resulting in no further treaties being negotiated1. This continued to be the policy until 1990 when British Columbia agreed to enter into the treaty negotiation process, and the B.C. Treaty Commission was developed. The Nisga Treaty is the first treaty to be negotiated since the Douglas Treaties. This paper intends to explore the Douglas Treaties and the implications of the Delgamuukw decision on these. What assistance does Delgamuukw provide in determining what lands are subject to aboriginal title? What aboriginal title lands did the Douglas people give up in the treaty process? What, if any, aboriginal title land has survived the treaty process? 1 Joseph Trutch, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works and Walter Moberly, Assistant Surveyor- General, initiated this policy. -

The Global Irish and Chinese: Migration, Exclusion, and Foreign Relations Among Empires, 1784-1904

THE GLOBAL IRISH AND CHINESE: MIGRATION, EXCLUSION, AND FOREIGN RELATIONS AMONG EMPIRES, 1784-1904 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Barry Patrick McCarron, M.A. Washington, DC April 6, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Barry Patrick McCarron All Rights Reserved ii THE GLOBAL IRISH AND CHINESE: MIGRATION, EXCLUSION, AND FOREIGN RELATIONS AMONG EMPIRES, 1784-1904 Barry Patrick McCarron, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Carol A. Benedict, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation is the first study to examine the Irish and Chinese interethnic and interracial dynamic in the United States and the British Empire in Australia and Canada during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Utilizing comparative and transnational perspectives and drawing on multinational and multilingual archival research including Chinese language sources, “The Global Irish and Chinese” argues that Irish immigrants were at the forefront of anti-Chinese movements in Australia, Canada, and the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century. Their rhetoric and actions gave rise to Chinese immigration restriction legislation and caused major friction in the Qing Empire’s foreign relations with the United States and the British Empire. Moreover, Irish immigrants east and west of the Rocky Mountains and on both sides of the Canada-United States border were central to the formation of a transnational white working-class alliance aimed at restricting the flow of Chinese labor into North America. Looking at the intersections of race, class, ethnicity, and gender, this project reveals a complicated history of relations between the Irish and Chinese in Australia, Canada, and the United States, which began in earnest with the mid-nineteenth century gold rushes in California, New South Wales, Victoria, and British Columbia. -

Gaming Revenue Granted To, and Earned by Community Organizations - 2013/14 Full Report (By Community)

Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch Gaming Revenue Granted to, and Earned by Community Organizations - 2013/14 Full Report (by community) Notes: ♦ Gaming event licence reported earnings as of July 4, 2014, including losses. It is estimated that total licensed gaming earnings in 2013/14 were approximately $37.8 million. ■ This report does not include, or show, unused grant funds returned by an organization. Grants Gaming Event Licences (reported earnings as of July 4, 2014) ♦ Social Community Special One Independent Wheel of City Organization Name Ticket Raffle Occasion Poker Total Gaming Grants Time Grants Bingo Fortune Casino 100 Mile House 100 Mile & District Minor Hockey Association $45,000.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $45,000.00 100 Mile House 100 Mile Elementary School PAC $6,200.00 $0.00 $0.00 $10.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $6,210.00 100 Mile House 100 Mile House & District Figure Skating Club $13,475.00 $0.00 $0.00 $86.99 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $13,561.99 100 Mile House 100 Mile House & District Women's Centre Society $17,000.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $17,000.00 100 Mile House 100 Mile House and District Soccer Association $26,160.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $26,160.00 100 Mile House 100 Mile House Community Club $0.00 $0.00 $24,071.56 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $24,071.56 100 Mile House 100 Mile House Food Bank Society $85,000.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $85,000.00 100 Mile House 100 Mile House Wranglers Junior B Hockey Club $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $13,501.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $13,501.00 100 Mile House -

OCTOBER TERM 1996 Reference Index Contents

JNL96$IND1Ð08-20-99 15:29:27 JNLINDPGT MILES OCTOBER TERM 1996 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics ....................................................................................... II General .......................................................................................... III Appeals ......................................................................................... III Arguments ................................................................................... III Attorneys ...................................................................................... IV Briefs ............................................................................................. IV Certiorari ..................................................................................... IV Costs .............................................................................................. V Judgments and Opinions ........................................................... V Original Cases ............................................................................. V Parties ........................................................................................... V Rehearings ................................................................................... VI Rules ............................................................................................. VI Stays .............................................................................................. VI Conclusion ................................................................................... -

News Clipping Files

News Clipping Files News Clipping File Title File Number Abkhazi Gardens (Victoria, B.C.) 3029 Abkhazi, Margaret, Princess 8029 Academy Close (Victoria, B.C.) 3090 Access to information 9892 Accidents 3287 Actors 3281 Adam, James, 1832-1939 3447 Adams, Daniel (family) 7859 Adaskin, Murray 6825 Adey, Muriel, Rev. 6826 Admirals Road (Esquimalt, B.C.) 2268 Advertising 45 Affordable housing 8836 Agnew, Kathleen 3453 Agricultural organizations 1989 Agriculture 1474 Air mail service 90 Air travel 2457 Airports 1573 Airshows 1856 Albert Avenue (Victoria, B.C.) 2269 Alder Street (Victoria, B.C.) 9689 Alexander, Charles, 1824-1913 (family) 6828 Alexander, Fred 6827 Alexander, Verna Irene, 1906-2007 9122 Alexander-Haslam, Patty (family) 6997 Alexis, Johnny 7832 Allen, William, 1925-2000 7802 Alleys 1947 Alting, Margaretha 6829 Amalgamation (Municipal government) 150 Amelia Street (Victoria, B.C.) 2270 Anderson, Alexander Caulfield 6830 Anderson, Elijah Howe, 1841-1928 6831 Andrews, Gerald Smedley 6832 Angela College (Victoria, B.C.) 2130 Anglican Communion 2084 Angus, James 7825 Angus, Ronald M. 7656 Animal rights organizations 9710 Animals 2664 Anscomb, Herbert, 1892-1972 (family) 3484 Anti-German riots, Victoria, B.C., 1915 1848 Antique stores 441 Apartment buildings 1592 City of Victoria Archives News Clipping Files Appliance stores 2239 Arbutus Road (Victoria, B.C.) 2271 Archaeology 1497 Archery 2189 Architects 1499 Architecture 1509 Architecture--Details 3044 Archivists 8961 Ardesier Road (Victoria, B.C.) 2272 Argyle, Thomas (family) 7796 Arion Male Voice Choir 1019 Armouries 3124 Arnold, Marjoriem, 1930-2010 9726 Arsens, Paul and Artie 6833 Art 1515 Art deco (Architecture) 3099 Art galleries 1516 Art Gallery of Greater Victoria 1517 Art--Exhibitions 1876 Arthur Currie Lane (Victoria, B.C.) 2853 Artists 1520 Arts and Crafts (Architecture) 3100 Arts organizations 1966 Ash, John, Dr. -

Edgar Crow Baker an Entrepreneur in Early British Columbia

EDGAR CROW BAKER AN ENTREPRENEUR IN EARLY BRITISH COLUMBIA by GEORGE WAITE STIRLING BROOKS B.A., University of Victoria, 1970 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES in the Department of Histcry We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF-BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1976 (E) George Waite Stirling Brooks, 19 7 6 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date ) D ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis is the nature of entre- preneurism in British Columbia from 187"+ until about 1905. The business affairs of one Victoria entrepreneur, Edgar Crow Baker, are used to examine the character of these men, their business endeavours and the society that they lived in. The era of the entrepreneur in British Columbia began with the Fraser River gold rush in 1858. It con• tinued until about the turn of the century, when the era of the corporate entrepreneur was ushered in with the arrival of large corporations from outside the province that began to buy up the smaller local companies. -

The Illumination of Victoria : Late Nineteenth-Century Technology and Municipal Enterprise

The Illumination of Victoria : Late Nineteenth-Century Technology and Municipal Enterprise PATRICIA ROY In 1886, the Victoria Colonist boasted of the "perfect lighting" of the city by electricity.1 That premature statement reflected Victoria's pride in being one of the first Canadian cities to have electric street lights but it also obscured the role of past and continuing local controversy as Victoria dealt with private lighting companies, a brand new technology and a municipal street lighting system. The story of Victoria's street lights falls into three phases. After con siderable debate over monopoly privileges and maximum prices, the privately owned Victoria Gas Company began to operate in 1863. Because of its unsatisfactory service and high prices, it was never popular and did not get a street lighting contract until 1873. By 1880, the street lighting question was entering a second phase as local residents debated the relative merits of gas and the new lighting medium, electricity. Finally, in order to improve the unsatisfactory electric street lighting system installed by a private entrepreneur and to forestall a repetition of its disputes with the gas company, the city, for pragmatic rather than ideological reasons, made the electric street lights a municipal enterprise. I When the Hudson's Bay Company post of Victoria suddenly became a "full-grown town" in 1858,2 it lacked most civic amenities, including street lights. Coal oil, paraffin and camphene lamps lit homes, stores and offices; the streets were dark. Yet when the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island received a request to incorporate a company to supply Victoria with gas, it refused to act before the town was incorporated, an event which did not occur until 1862. -

Fort Victoria F 1089

OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES rADt3 III III 11111111liiiI 111111111 d50 12 0143738249 FORT VICTORIA F 1089. 5 V6 p53 1967 from Fur Trading Post to Capital City of BRITISH COLUMBIA. CANADA Paddle-wheel steamer "Beaver" ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: We wish to acknowledge with thanks the co-operation of the Provincial Archives in Victoria, B.C.. James K. Nesbitt, and the Colonist Printers Ltd. For further study se recommend the following literature: Early History of the Province of British Columbia, by B. A. McKelvie. The Founding of Fort Victoria, by W. Kaye Lamb. Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria, by E. C. Fawcett. The Makers of Canada, by Rev. George Bryce, D.D. A Brief History of the Hudson's Bay company, published by the HUdSOrIS Bay Company. The Story of the Canadian Fur Trade, by W. A. McKay in The Beaver, Magazine of the North, published by the Hudson's Bay Company. FORT VICTORIA from Fur Trading Post to Capital City of BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA by DR. HERBERT P. PLASTERER The Founding of Fort Victoria Vancouver's Island 45 The Hudson's Bay Company 6-8 The Oregon Treaty 9 Fort Victoria, the Fur Trading Post The Beginning 10-11 Building the Fort 12-17 Life in the Fort 18-25 Men Connected With Fort Victoria 26-30 The Goidrush and Its Effects 31-33 The Fort is Outgrown 3435 The City of Victoria Incorporation 36-37 Directory 38 Vancouver's Island Vancouver Island was first brought to the attention of the British government in 1784 through the journals of Captain James Cook. -

Orkney Library & Archive D1

Orkney Library & Archive D1: MISCELLANEOUS SMALL GIFTS AND DEPOSITS D1/1 Kirkwall Gas Works and Stromness Gas Works Plans 1894-1969 Plans of lines of gas pipes, Kirkwall, 1910-1967; Kirkwall Gas Works, layout and miscellaneous plans, 1894-1969; Stromness Gas Works plans, 1950-1953. 1.08 Linear Metres Some allied material relating to gas undertakings is in National Archives of Scotland and plans and photographs in Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. D1/2 Charter by Robert, Earl of Orkney to Magnus Cursetter 1587 & 1913 Charter by Robert, Earl of Orkney to Magnus Cursetter of lands of Wasdale and others (parish of Firth), 1587; printed transcript of the charter, 1913. The transcription was made by the Reverend Henry Paton, M.A. 0.01 Linear Metres D1/3 Papers relating to rental of lands in island of Rousay 1742-1974 Rental of lands in island of Rousay, 1742; correspondence about place of manufacture of paper used in the rental, 1973-1974. 0.01 Linear Metres English D1/4 Eday Peat Company records 1926-1965 Financial records, 1931-1965; Workmen’s time books, 1930-1931, 1938-1942; Letter book, 1926-1928; Incoming correspondence, 1929-1945; Miscellaneous papers, 1926-1943, including trading accounts (1934-1943). 0.13 Linear Metres English D1/5 Craigie family, Harroldsgarth, Shapinsay, papers 1863-1944 Rent book, 1863-1928; Correspondence about purchase and sale of Harroldsgarth, 1928-1944; Miscellaneous papers, 20th cent, including Constitution and Rules of the Shapansey Medical Asssociation. 0.03 Linear Metres English D1/6 Business papers of George Coghill, merchant, Buckquoy 1871-1902 Business letters, vouchers and memoranda of George Coghill, 1874- 1902; Day/cash book, 1871.