CROSSING HITLER the Man Who Put the Nazis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'antonio, Michael Senior Thesis.Pdf

Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Degree in History with Distinction Spring 2016 © 2016 Michael D’Antonio All Rights Reserved Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. James Brophy Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. David Shearer Committee member from the Department of History Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Barbara Settles Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This senior thesis would not have been possible without the assistance of Dr. James Brophy of the University of Delaware history department. His guidance in research, focused critique, and continued encouragement were instrumental in the project’s formation and completion. The University of Delaware Office of Undergraduate Research also deserves a special thanks, for its continued support of both this work and the work of countless other students. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. -

Knowledge Organiser: Hitler's Rise to Power, 1919-33

Knowledge organiser: Hitler’s Rise to Power, 1919-33 Hitler joined the Nazi Party in 1919 and was Chronology: what happened on these dates? Vocabulary: define these words. influential in defining its beliefs. He also led the Hitler joined the German Workers’ Party (DAP). In Private armies set up by Munich Putsch in 1923. However, from 1924 to 1929 1919 DAP, Hitler discovered he was good at public Freikorps senior German army officers the unpopular party gained little electoral success. speaking. at the end of WW1. The belief that land, industry Summarise your learning Hitler set up the Nazi Party. The party was based During the five years after the war, 1920 Socialism and wealth should be owned on the Twenty-Five Point Programme. several new parties emerged, by the state. Topic 1: including DAP. As it grew, it added The Munich Putsch was an attempt to overthrow The belief that the interests of The the words ‘national’ and ‘socialist’ to 1923 the Weimar Republic, which would allow Hitler to Nationalism a particular nation-state are development become the NSDAP and acquired the form his own Nazi government. of primary importance. of the Nazi new leader, Hitler. The party carried Party, 1920- When the US stock market collapsed in October – Literally ‘of the people’. In out the Munich Putsch, but failed. In 29 the Wall Street Crash – the problems created had Völkisch Germany it was linked to the years 1925-28 Hitler reorganised huge consequences for the German economy. extreme German nationalism. the Nazi Party. 1929 The death of Stresemann also added to the crisis. -

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

The Monita Secreta Or, As It Was Also Known As, The

James Bernauer, S.J. Boston College From European Anti-Jesuitism to German Anti-Jewishness: A Tale of Two Texts “Jews and Jesuits will move heaven and hell against you.” --Kurt Lüdecke, in conversation with Adolf Hitleri A Presentation at the Conference “Honoring Stanislaw Musial” Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland (March 5, 2009) The current intense debate about the significance of “political religion” as a mode of analyzing fascism leads us to the core of the crisis in understanding the Holocaust.ii Saul Friedländer has written of an “historian‟s paralysis” that “arises from the simultaneity and the interaction of entirely heterogeneous phenomena: messianic fanaticism and bureaucratic structures, pathological impulses and administrative decrees, archaic attitudes within an advanced industrial society.”iii Despite the conflicting voices in the discussion of political religion, the debate does acknowledge two relevant facts: the obvious intermingling in Nazism of religious and secular phenomena; secondly, the underestimated role exercised by Munich Catholicism in the early life of the Nazi party.iv My essay is an effort to illumine one thread in this complex territory of political religion and Nazism and my title conveys its hypotheses. First, that the centuries long polemic against the Roman Catholic religious order the Jesuits, namely, its fabrication of the Jesuit image as cynical corrupter of Christianity and European culture, provided an important template for the Nazi imagining of Jewry after its emancipation.v This claim will be exhibited in a consideration of two historically influential texts: the Monita 1 secreta which demonized the Jesuits and the Protocols of the Sages of Zion which diabolized the Jews.vi In the light of this examination, I shall claim that an intermingled rhetoric of Jesuit and Jewish wills to power operated in the imagination of some within the Nazi leadership, the most important of whom was Adolf Hitler himself. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

III. Zentralismus, Partikulare Kräfte Und Regionale Identitäten Im NS-Staat Michael Ruck Zentralismus Und Regionalgewalten Im Herrschaftsgefüge Des NS-Staates

III. Zentralismus, partikulare Kräfte und regionale Identitäten im NS-Staat Michael Ruck Zentralismus und Regionalgewalten im Herrschaftsgefüge des NS-Staates /. „Der nationalsozialistische Staat entwickelte sich zu einem gesetzlichen Zentralismus und zu einem praktischen Partikularismus."1 In dürren Worten brachte Alfred Rosen- berg, der selbsternannte Chefideologe des „Dritten Reiches", die institutionellen Unzu- länglichkeiten totalitärer Machtaspirationen nach dem „Zusammenbruch" auf den Punkt. Doch öffnete keineswegs erst die Meditation des gescheiterten „Reichsministers für die besetzten Ostgebiete"2 in seiner Nürnberger Gefängniszelle den Blick auf die vielfältigen Diskrepanzen zwischen zentralistischem Herrschafts<*«s/>r«c/> und fragmen- tierter Herrschaftspraus im polykratischen „Machtgefüge" des NS-Regimes3. Bis in des- sen höchste Ränge hinein hatte sich diese Erkenntnis je länger desto mehr Bahn gebro- chen. So beklagte der Reichsminister und Chef der Reichskanzlei Hans-Heinrich Lammers, Spitzenrepräsentant der administrativen Funktionseliten im engsten Umfeld des „Füh- rers", zu Beginn der vierziger Jahre die fortschreitende Aufsplitterung der Reichsver- waltung in eine Unzahl alter und neuer Behörden, deren unklare Kompetenzen ein ge- ordnetes, an Rationalitäts- und Effizienzkriterien orientiertes Verwaltungshandeln zuse- hends erschwerten4. Der tiefgreifenden Frustration, welche sich der Ministerialbürokra- tie ob dieser Zustände bemächtigte, hatte Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg schon 1 Alfred Rosenberg, Letzte Aufzeichnungen. Ideale und Idole der nationalsozialistischen Revo- lution, Göttingen 1955, S.260; Hervorhebungen im Original. Vgl. dazu Dieter Rebentisch, Führer- staat und Verwaltung im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Verfassungsentwicklung und Verwaltungspolitik 1939-1945, Stuttgart 1989, S.262; ders., Verfassungswandel und Verwaltungsstaat vor und nach der nationalsozialistischen Machtergreifung, in: Jürgen Heideking u. a. (Hrsg.), Wege in die Zeitge- schichte. Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Gerhard Schulz, Berlin/New York 1989, S. -

The Kpd and the Nsdap: a Sttjdy of the Relationship Between Political Extremes in Weimar Germany, 1923-1933 by Davis William

THE KPD AND THE NSDAP: A STTJDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN POLITICAL EXTREMES IN WEIMAR GERMANY, 1923-1933 BY DAVIS WILLIAM DAYCOCK A thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. The London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London 1980 1 ABSTRACT The German Communist Party's response to the rise of the Nazis was conditioned by its complicated political environment which included the influence of Soviet foreign policy requirements, the party's Marxist-Leninist outlook, its organizational structure and the democratic society of Weimar. Relying on the Communist press and theoretical journals, documentary collections drawn from several German archives, as well as interview material, and Nazi, Communist opposition and Social Democratic sources, this study traces the development of the KPD's tactical orientation towards the Nazis for the period 1923-1933. In so doing it complements the existing literature both by its extension of the chronological scope of enquiry and by its attention to the tactical requirements of the relationship as viewed from the perspective of the KPD. It concludes that for the whole of the period, KPD tactics were ambiguous and reflected the tensions between the various competing factors which shaped the party's policies. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE abbreviations 4 INTRODUCTION 7 CHAPTER I THE CONSTRAINTS ON CONFLICT 24 CHAPTER II 1923: THE FORMATIVE YEAR 67 CHAPTER III VARIATIONS ON THE SCHLAGETER THEME: THE CONTINUITIES IN COMMUNIST POLICY 1924-1928 124 CHAPTER IV COMMUNIST TACTICS AND THE NAZI ADVANCE, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW THREATS 166 CHAPTER V COMMUNIST TACTICS, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW OPPORTUNITIES 223 CHAPTER VI FLUCTUATIONS IN COMMUNIST TACTICS DURING 1932: DOUBTS IN THE ELEVENTH HOUR 273 CONCLUSIONS 307 APPENDIX I VOTING ALIGNMENTS IN THE REICHSTAG 1924-1932 333 APPENDIX II INTERVIEWS 335 BIBLIOGRAPHY 341 4 ABBREVIATIONS 1. -

Cr^Ltxj

THE NAZI BLOOD PURGE OF 1934 APPRCWBD": \r H M^jor Professor 7 lOLi Minor Professor •n p-Kairman of the DeparCTieflat. of History / cr^LtxJ~<2^ Dean oiTKe Graduate School IV Burkholder, Vaughn, The Nazi Blood Purge of 1934. Master of Arts, History, August, 1972, 147 pp., appendix, bibliography, 160 titles. This thesis deals with the problem of determining the reasons behind the purge conducted by various high officials in the Nazi regime on June 30-July 2, 1934. Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goring, SS leader Heinrich Himmler, and others used the purge to eliminate a sizable and influential segment of the SA leadership, under the pretext that this group was planning a coup against the Hitler regime. Also eliminated during the purge were sundry political opponents and personal rivals. Therefore, to explain Hitler's actions, one must determine whether or not there was a planned putsch against him at that time. Although party and official government documents relating to the purge were ordered destroyed by Hermann GcTring, certain materials in this category were used. Especially helpful were the Nuremberg trial records; Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919-1939; Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945; and Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic Papers, 1934. Also, first-hand accounts, contem- porary reports and essays, and analytical reports of a /1J-14 secondary nature were used in researching this topic. Many memoirs, written by people in a position to observe these events, were used as well as the reports of the American, British, and French ambassadors in the German capital. -

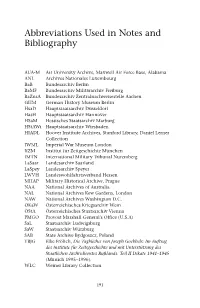

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Extreme Right Transnationalism: International Networking and Cross-Border Exchanges

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. Extreme Right Transnationalism: International Networking and Cross-Border Exchanges Paul Jackson Senior Lecturer in History, University of Northampton Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH While many historians have devoted themselves to forms of anti-fascism: divisions within the left. The examining the dynamics of fascist movements and Italian Communist Party was also formed at this time, regimes, the topic of ‘anti-fascism’ has traditionally and while initially supportive of the Arditi del Popolo, been neglected. However, historians and other later it instructed its members to withdraw their academics are now starting to take greater interest in engagement. The Arditi del Popolo was shut down by the study of those who opposed nationalist and racist the Italian state by 1924, while the Italian Communist extremists, and are developing new approaches to Party was itself banned from 1926. Splits within the understanding these complex cultures. Some, such as left have often been a characteristic of anti-fascist Nigel Copsey, have been concerned with developing politics, and in Italy during the 1920s such anti- sober, empirical accounts, exploring left-wing, centre fascists were driven by competing ideas on how to and even right-wing forms of anti-fascism, presenting develop an anti-capitalist revolution. In this case, the it as a heterogeneous politicised identity. Others, such issue helped to foster discord between a more as Mark Bray, have been more concerned with eclectic and anarchist variant of anti-fascism and a developing unapologetically partisan readings of the more centralised Communist version. -

Exclusion After the Seizure of Power

Exclusion after the Seizure of Power 24 | L A W YE RS W I T H O U T R IGH T S The first Wave of Exclusion: Terroristic Attacks Against Jewish Attorneys After (Adolph) Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor and a coalition government was formed that included German nationalists, the National Socialists increased the level of national terror. The Reichstag fire during the night of Feb. 28, 1933 served as a signal to act. It provided the motive to arrest more than 5,000 political opponents, especially Communist officials and members of the Reichstag, as well as Social Democrats and other opponents of the Nazis. The Dutch Communist Marinus van der Lubbe, who was arrested at the scene of the crime, was later sentenced to death and executed. It was for this reason that, on March 29, 1933— afterwards—a special law was enacted that increased criminal penalties, because up to then the maximum punishment for arson had been penal servitude. The other four accused, three Bulgarian Communists (among them the well-known Georgi Dimitroff) and a German Communist, Ernst Torgler, were acquitted by the Reichsgericht, the Weimar Republic’s highest court, in Leipzig. On the day of the Reichstag fire, Reich President von Hindenburg signed the emergency decree “For the Protection of the People and the State.” This so-called “Reichstag fire decree” suspended key basic civil rights: personal freedom, freedom of speech, of the press, of association and assembly, the confidentiality of postal correspondence and tele- phone communication, the inviolability of property and the home. At the beginning of February another emergency decree was promulgated that legalized “protective custody,” which then proceeded to be used as an arbitrary instrument of terror. -

PSS Holocaust FM

TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Stephen Feinstein, Director, Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies . .xiii Preface . .xvii Introduction . 1 Chapter 1: Roots of Anti-Semitism . 3 Introduction . .5 1.1 Anti-Semitism from a Christian Religious Leader – 1543 . .9 Excerpt from “On Jews and Their Lies” by Martin Luther 1.2 Arguing the Superiority of the “Aryan” Race – 1853 . .15 Excerpt from The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races by Joseph Arthur Comte de Gobineau 1.3 Racist Theory on Aryans and Jews – 1899 . .20 Excerpt from The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century by Houston Stewart Chamberlain 1.4 The Myth of a Jewish Conspiracy – 1903 . .27 Excerpt from Protocols of the Meetings of the Zionist Men of Wisdom Chapter 2: World War I and the Rise of the Nazi Party . 31 Introduction . .33 2.1 The Treaty of Versailles – 1919 . .37 Text of the Treaty of Peace Between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany 2.2 The Nazis Spell Out Their Political Goals – 1920 . .43 Program of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party 2.3 Social and Economic Upheaval in Postwar Germany – 1920s . .47 Excerpt from The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig v The Holocaust 2.4 Hitler Casts Himself as a Patriot – 1923 . .51 Excerpts from Adolf Hitler’s Trial Address after the Beer Hall Putsch 2.5 Hitler Rages against the Jews – 1923 . .53 Excerpt from Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler 2.6 A Childhood Shadowed by Anti-Semitism – 1920s . .62 Holocaust Survivor Henry Oertelt Remembers the Brown Shirts 2.7 Germany’s “Enabling Law” – 1933 .