The Orange Pennant: the Dutch Response to a Flag Dilemma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orange in the South Cance

The colour of monarchs and merriment The Dutch monarchy has mostly ceremonial signifi- also inherited the principality of Orange in the south cance. Although not passionate royalists, most Dutch of France, so that in the mid-1500s, the title ‘Prince of feel quite comfortable with the constitutional mon- Orange’, together with the possessions of the Nassaus archy. Once a year, on Koningsdag (King’s Day), the in the Low Countries, ended up with a certain William, country dresses up in orange and the royal family is a nicknamed ‘the Silent’. At the time, the Netherlands source of communal celebration. was an unwilling part of a large Spanish kingdom, and the influential William gradually became the leader of On Koningsdag, April 27, the Netherlands celebrates the resistance to the Spanish domination. Partly on Wil- the King’s birthday. In most towns and villages large liam’s initiative, seven regions joined together in revolt. markets are held, surrounded by all manner of festivi- ties. Full of good cheer and draped in orange, the Dutch On the King’s birthday, he visits crowd market stalls and terraces, and the party ends in traditional demonstrations of sack racing, fireworks and, for many, a hefty Orange hangover. The monarch joins the celebrations, traditionally clog-making and herring-gutting. visiting two towns in which he is treated to demon- strations of sack racing, clog-making, herring-gutting 01 King’s Day celebrations on an Amsterdam canal 02 Orange treats and other traditional activities. Willem-Alexander (or 03 Tin containing orange sprinkles and showing the portrait of the ‘Alex’, as he is popularly known) shows his best side, former Queen Beatrix 04 Celebrating King’s Day shaking hands and showing interest in every drawing handed to him by beaming pre-schoolers. -

William Herle's Report of the Dutch Situation, 1573

LIVES AND LETTERS, VOL. 1, NO. 1, SPRING 2009 Signs of Intelligence: William Herle’s Report of the Dutch Situation, 1573 On the 11 June 1573 the agent William Herle sent his patron William Cecil, Lord Burghley a lengthy intelligence report of a ‘Discourse’ held with Prince William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Netherlands.∗ Running to fourteen folio manuscript pages, the Discourse records the substance of numerous conversations between Herle and Orange and details Orange’s efforts to persuade Queen Elizabeth to come to the aid of the Dutch against Spanish Habsburg imperial rule. The main thrust of the document exhorts Elizabeth to accept the sovereignty of the Low Countries in order to protect England’s naval interests and lead a league of protestant European rulers against Spain. This essay explores the circumstances surrounding the occasion of the Discourse and the context of the text within Herle’s larger corpus of correspondence. In the process, I will consider the methods by which the study of the material features of manuscripts can lead to a wider consideration of early modern political, secretarial and archival practices. THE CONTEXT By the spring of 1573 the insurrection in the Netherlands against Spanish rule was seven years old. Elizabeth had withdrawn her covert support for the English volunteers aiding the Dutch rebels, and was busy entertaining thoughts of marriage with Henri, Duc d’Alençon, brother to the King of France. Rejecting the idea of French assistance after the massacre of protestants on St Bartholomew’s day in Paris the previous year, William of Orange was considering approaching the protestant rulers of Europe, mostly German Lutheran sovereigns, to form a strong alliance against Spanish Catholic hegemony. -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

Colour Psychology Colour and Culture

74 COLOUR PSYCHOLOGY COLOUR AND CONTRAST 75 Colour Psychology Colour and Culture How people respond to colour is of great interest to those who work Research shows that ninety-eight languages have words for the same in marketing. Colour psychology research is often focused on how eleven basic colours;4 however, the meaning a colour may have can be the colour of a logo or a product will yield higher sales, and what very different. There are conflicting theories on whether the cultural colour preferences can be found in certain age groups and cultures. meanings of colours can be categorised. Meanings can change over The study of the psychological effects of colour have coincided time and depend on the context. Black may be the colour of mourning with colour theory in general. Goethe focused on the experience of in many countries, though a black book cover or a black poster is not colour in his Zur farbenlehre from 1810,1 in opposition to Sir Isaac always associated with death. Another example is that brides in China Newton’s rational approach. Goethe and Schiller coupled colours to traditionally wear red, but many brides have started to wear white in character traits: red for beautiful, yellow for good, green for useful, recent decades.4 The cultural meaning of colours is not set but always and blue for common. Gestalt psychology in the early 1900s also changing. The next few pages list some of the meanings of colours in attributed universal emotions to colours, a theory that was taught to different cultures. students at the Bauhaus by Wassily Kandinsky. -

Criminal Code

Criminal Code Warning: this is not an official translation. Under all circumstances the original text in Dutch language of the Criminal Code (Wetboek van Strafrecht) prevails. The State accepts no liability for damage of any kind resulting from the use of this translation. Criminal Code (Text valid on: 01-10-2012) Act of 3 March 1881 We WILLEM III, by the grace of God, King of the Netherlands, Prince of Orange-Nassau, Grand Duke of Luxemburg etc. etc. etc. Greetings to all who shall see or hear these presents! Be it known: Whereas We have considered that it is necessary to enact a new Criminal Code; We therefore, having heard the Council of State, and in consultation with the States General, have approved and decreed as We hereby approve and decree, to establish the following provisions which shall constitute the Criminal Code: Book One. General Provisions Part I. Scope of Application of Criminal Law Section 1 1. No act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offence under the law at the time of its commission shall be punishable by law. 2. Where the statutory provisions in force at the time when the criminal offence was committed are later amended, the provisions most favourable to the suspect or the defendant shall apply. Section 2 The criminal law of the Netherlands shall apply to any person who commits a criminal offence in the Netherlands. Section 3 The criminal law of the Netherlands shall apply to any person who commits a criminal offence on board a Dutch vessel or aircraft outside the territory of the Netherlands. -

Anneke Jans' Maternal Grandfather and Great Grandfather

Anneke Jans’ Maternal Grandfather and Great Grandfather By RICIGS member, Gene Eiklor I have been writing a book about my father’s ancestors. Anneke Jans is my 10th Great Grandmother, the “Matriarch of New Amsterdam.” I am including part of her story as an Appendix to my book. If it proves out, Anneke Jans would be the granddaughter of Willem I “The Silent” who started the process of making the Netherlands into a republic. Since the records and info about Willem I are in the hands of the royals and government (the Royals are buried at Delft under the tomb of Willem I) I took it upon myself to send the Appendix to Leiden University at Leiden. Leiden University was started by Willem I. An interesting fact is that descendants of Anneke have initiated a number of unsuccessful attempts to recapture Anneke’s land on which Trinity Church in New York is located. In Chapter 2 – Dutch Settlement, page 29, Anneke Jans’ mother was listed as Tryntje (Catherine) Jonas. Each were identified as my father’s ninth and tenth Great Grandmothers, respectively. Since completion of that and succeeding chapters I learned from material shared by cousin Betty Jean Leatherwood that Tryntje’s husband had been identified. From this there is a tentative identification of Anneke’s Grandfather and Great Grandfather. The analysis, the compilation and the writings on these finds were done by John Reynolds Totten. They were reported in The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Volume LVI, No. 3, July 1925i and Volume LVII, No. 1, January 1926ii Anneke is often named as the Matriarch of New Amsterdam. -

FLAG of MONACO - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF MONACO - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia Apart from aspect ratio, the flag of Monaco is identical to the flag of Indonesia. Technical Specification Adopted: 1881 Proportion: 4:5 Design: A bi-colour in red and white, from top to bottom Colours: PMS: Red: 032 C CMYK: Red: 0% Cyan, 90% Magenta, 86% Yellow, 0% Black Brief History Monaco used to be a colony of the Italian city-state Genoa. A small isolated country between the mountains and the sea with one castle on the Rock of Monaco, overlooking the entire country. Francesco Grimaldi disguised himself and his men as Franciscan monks and infiltrated the castle to take control. It was not long before Genoan forces succeeded in ousting him. Later his descendents simply bought the castle and the realm from Genoa and turned it into a principality. At this point the flag of Genoa was the St. George’s flag. They allowed England, for a fee, to fly their flag so they could use their sea and ports to trade. The Monaco Coat of Arms has represented the country for as long as the Grimaldi dynasty has been in power, since the early 15th Century. Although the design has changed gradually over the years, the key elements have remained the same. The motto, 'Deo Juvante' is Latin for 'With God's Help'. This coat of arms today serves as the state flag. St George’s Flag of Genoa The Coat of Arms of Monaco The colours on the shield, red and white in a pattern known as 'lozengy argent and gules' in heraldic terms, are the national colours. -

Flags of Asia

Flags of Asia Item Type Book Authors McGiverin, Rolland Publisher Indiana State University Download date 27/09/2021 04:44:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/12198 FLAGS OF ASIA A Bibliography MAY 2, 2017 ROLLAND MCGIVERIN Indiana State University 1 Territory ............................................................... 10 Contents Ethnic ................................................................... 11 Afghanistan ............................................................ 1 Brunei .................................................................. 11 Country .................................................................. 1 Country ................................................................ 11 Ethnic ..................................................................... 2 Cambodia ............................................................. 12 Political .................................................................. 3 Country ................................................................ 12 Armenia .................................................................. 3 Ethnic ................................................................... 13 Country .................................................................. 3 Government ......................................................... 13 Ethnic ..................................................................... 5 China .................................................................... 13 Region .................................................................. -

Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a Case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian Group in Toronto

Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a Case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian Group in Toronto By Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Trinity College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar 2016 Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian group in Toronto PhD 2016 Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar University of St.Michael’s College Abstract This study explores how the Macedono-Bulgarian and Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox churches in Toronto have attuned themselves to the immigrant community—specifically to post-1990 immigrants who, while unchurched and predominantly secular, have revived diaspora churches. This paradox raises questions about the ways that religious institutions operate in diaspora, distinct from their operations in the country of origin. This study proposes and develops the concept “institutional vernacularization” as an analytical category that facilitates assessment of how a religious institution relates to communal factors. I propose this as an alternative to secularization, which inadequately captures the diaspora dynamics. While continuing to adhere to their creeds and confessional symbols, diaspora churches shifted focus to communal agency and produced new collective and “popular” values. The community is not only a passive recipient of the spiritual gifts but is also a partner, who suggests new forms of interaction. In this sense, the diaspora church is engaged in vernacular discourse. The notion of institutional vernacularization is tested against the empirical results of field work in four Greater Toronto Area churches. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

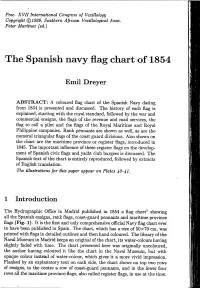

Proc. XVII International Congress of Vexillology Copyright ©1999, Southern African Vexillological ^ssn. Peter Martinez (ed.) The Spanish navy flag chart of 1854 Emil Dreyer ABSTRACT: A coloured flag chart of the Spanish Navy dating from 1854 is presented and discussed. The history of each flag is explained, starting with the royal standard, followed by the war and commercial ensigns, the flags of the revenue and mail services, the flag to call a pilot and the flags of the Royal Maritime and Royal Philippine companies. Rank pennants are shown as well, as are the numeral triangular flags of the coast guard divisions. Also shown on the chart are the maritime province or register flags, introduced in 1845. The important influence of these register flags on the develop ment of Spanish civic flags and yacht club burgees is discussed. The Spanish text of the chart is entirely reproduced, followed by extracts of English translation. The illustrations for this paper appear on Plates 40~41- 1 Introduction The Hydrographic Office in Madrid published in 1854 a flag chart^ showing all the Spanish ensigns, rank flags, coast-guard pennants and maritime province flags (Fig. 1). It is the flrst and only comprehensive official Navy flag chart ever to have been published in Spain. The chart, which has a size of 50x70 cm, was printed with flags in detailed outlines and then hand coloured. The library of the Naval Museum in Madrid keeps an original of the chart, its water-colours having slightly faded with time. The chart presented here was originally uncoloured, the author having coloured it like the chart in the Naval Museum, but with opaque colour instead of water-colour, which gives it a more vivid impression. -

Ambassadors to and from England

p.1: Prominent Foreigners. p.25: French hostages in England, 1559-1564. p.26: Other Foreigners in England. p.30: Refugees in England. p.33-85: Ambassadors to and from England. Prominent Foreigners. Principal suitors to the Queen: Archduke Charles of Austria: see ‘Emperors, Holy Roman’. France: King Charles IX; Henri, Duke of Anjou; François, Duke of Alençon. Sweden: King Eric XIV. Notable visitors to England: from Bohemia: Baron Waldstein (1600). from Denmark: Duke of Holstein (1560). from France: Duke of Alençon (1579, 1581-1582); Prince of Condé (1580); Duke of Biron (1601); Duke of Nevers (1602). from Germany: Duke Casimir (1579); Count Mompelgart (1592); Duke of Bavaria (1600); Duke of Stettin (1602). from Italy: Giordano Bruno (1583-1585); Orsino, Duke of Bracciano (1601). from Poland: Count Alasco (1583). from Portugal: Don Antonio, former King (1581, Refugee: 1585-1593). from Sweden: John Duke of Finland (1559-1560); Princess Cecilia (1565-1566). Bohemia; Denmark; Emperors, Holy Roman; France; Germans; Italians; Low Countries; Navarre; Papal State; Poland; Portugal; Russia; Savoy; Spain; Sweden; Transylvania; Turkey. Bohemia. Slavata, Baron Michael: 1576 April 26: in England, Philip Sidney’s friend; May 1: to leave. Slavata, Baron William (1572-1652): 1598 Aug 21: arrived in London with Paul Hentzner; Aug 27: at court; Sept 12: left for France. Waldstein, Baron (1581-1623): 1600 June 20: arrived, in London, sightseeing; June 29: met Queen at Greenwich Palace; June 30: his travels; July 16: in London; July 25: left for France. Also quoted: 1599 Aug 16; Beddington. Denmark. King Christian III (1503-1 Jan 1559): 1559 April 6: Queen Dorothy, widow, exchanged condolences with Elizabeth.