Durga Idols of Kumartuli: Surviving Oral Traditions Through Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coordinator, Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC)

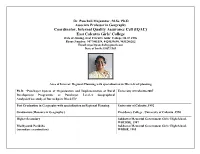

Dr. Panchali Majumdar, M.Sc, Ph.D Associate Professor in Geography Coordinator, Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) East Calcutta Girls’ College Date of Joining, East Calcutta Girls’ College: 01.07.1996 Phone Number: 9477001138, 8420539690, 9433246262 Email:[email protected] Date of birth:19.07.1969 Area of Interest: Regional Planning with specialization in Micro-level planning Ph.D: “Panchayet System of Organisation and Implementation of Rural University of Calcutta,2007 Development Programme at Panchayet Level-A Geographical Analysis(Case study of Barrackpore Block II)” Post Graduation in Geography with specialization in Regional Planning University of Calcutta ,1992 Graduation (Honours in Geography ) Presidency College , University of Calcutta ,1990 Higher Secondary Sakhawat Memorial Government Girls’ High School, WBCHSE, 1987 Madhyamik Pariksha Sakhawat Memorial Government Girls’ High School, (secondary examination) WBBSE, 1985 Other Awarded as NSS CO-ORDINATOR Governing Member of Post Graduate Board of Studies, Activities Programme Officer Internal Quality Body East Calcutta Girls’ College. Invitee member Assurance Cell (IQAC) member for of UG BOS , Burdwan University,2018.Acted for 2012-2013,2013- three(3) term East Calcutta Girls’ as Editorial Board Member in ,Environment 14, 2014-2015 period. College from 2015. Acted as and Sustainability-A Geographical Incharge of Perspective, ISBN:978-93-83010-29-5,2016. Member of IQAC, ECGC the College on from2010. 06.04.2016, 20.04.2016, 15.6.2017 to 16.06.2017, 30.8.17 to 16.09.2017. Teaching Acted as Head Examiner, Taking regular classes in Invited in Post Graduate studies (regular ) in Experience Moderator, Examiner , Post Graduate course Ashutosh College from 2011 to 2019, Barrackpore Scrutineer, Paper Setter in (Regular), in East Calcutta Rastraguru Surendranath College from 2014 to Unergraduate and Post Girls’ College 2018. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Paper Code: Dttm C205 Tourism in West Bengal Semester

HAND OUT FOR UGC NSQF SPONSORED ONE YEAR DILPOMA IN TRAVEL & TORUISM MANAGEMENT PAPER CODE: DTTM C205 TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL SEMESTER: SECOND PREPARED BY MD ABU BARKAT ALI UNIT-I: 1.TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL: AN OVERVIEW Evolution of Tourism Department The Department of Tourism was set up in 1959. The attention to the development of tourist facilities was given from the 3 Plan Period onwards, Early in 1950 the executive part of tourism organization came into being with the appointment of a Tourist Development Officer. He was assisted by some of the existing staff of Home (Transport) Department. In 1960-61 the Assistant Secretary of the Home (Transport) Department was made Director of Tourism ex-officio and a few posts of assistants were created. Subsequently, the Secretary of Home (Transport) Department became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Two Regional Tourist Offices - one for the five North Bengal districts i.e., Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, West Dinajpur and Maida with headquarters at Darjeeling and the other for the remaining districts of the State with headquarters at Kolkata were also set up. The Regional Office at KolKata started functioning on 2nd September, 1961. The Regional Office in Darjeeling was started on 1st May, 1962 by taking over the existing Tourist Bureau of the Govt. of India at Darjeeling. The tourism wing of the Home (Transport) Department was transferred to the Development Department on 1st September, 1962. Development. Commissioner then became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Subsequently, in view of the increasing activities of tourism organization it was transformed into a full-fledged Tourism Department, though the Secretary of the Forest Department functioned as the Secretary, Tourism Department. -

Multiple Choice Questions (Mcqs) with Answers Q1- Aurangzeb Died

Class 8 History Chapter 2 “From Trade to Territory” Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) with Answers Q1- Aurangzeb died in the year A) 1707 B) 1710 C) 1705 D) 1711 Q2- ______ was the last ruler of Mughal empire. A) Akbar II B) Bahadur Shah Zafar C) Aurangzeb D) Shah Alam II Q3- _____ granted a Charter to East India Company in early 1600s in order to trade with India A) Queen Elizabeth I B) Queen Victoria C) King George V D) Queen Elizabeth II Q4- _____ was the first person to discover a trading route to India. A) Vasco da Gama B) James Cook C) Columbus D) Thomas Cook Q5- Portugese were first to discover sea route to India in _____ A) 1490 B) 1496 C) 1498 D) 1500 Q6- Fine qualities of ____ had big market in Europe when European traders started marketing in India. A) cotton B) timber C) wheat D) pepper Q7- The first English company came up in the year ____ A) 1666 B) 1651 C) 1652 D) 1655 Q8- Kalikata is the old name of A) Calicut B) Kozhikode C) Kolkata D) Madras Q9- Battle of Plassey took place in the year A) 1757 B) 1789 C) 1760 D) 1755 Q10- During late 1690s, the Nawab of Bengal was A) Akbar II B) Khuda Baksh C) Shujauddaulah D) Murshid Quli Khan Q11– Alivardi Khan passed away in the year A) 1756 B) 1791 C) 1780 D) 1777 Q12 ______ was the first major victory of Englishmen in India. A) Battle of Plassey B) Battle of Madras C) battle of Mysore D) Battle of Delhi Q13- _____ led Englishmen in the Battle of Plassey against Bengal nawab in 1757 A) Warren Hasting B) Louis Mountbaitten C) Robert Clive D) Lord Canning Q14- _____ were appointed by -

PAPER 1 DSE-A-1 SEM -5: HISTORY of BENGAL(C.1757-1905) I

PAPER 1 DSE-A-1 SEM -5: HISTORY OF BENGAL(c.1757-1905) I. POLITICAL HISTORY OF BENGAL UNDER THE NAWABS:RISE OF BRITISH POWER IN BENGAL FROM THE BATTLE OF PLASSEY TO BUXAR. The beginning of British rule in India may be traced to the province of Bengal which emerged as the base from which the British first embarked on their political career that would last for almost two centuries. After the death of Aurangzeb various parts of the Mughal Empire became independent under different heads. Bengal became independent under the leadership of Alivardi Khan who maintained friendly relation with the English officials throughout his reign. However he did not allow them to fortify their settlements till the end of his rule up to 1756CE. Alivardi Khan was succeded by his grandson Nawab Shiraj –ud-Daulah who as soon as ascending the throne demanded of the English that they should trade on the same basis as in the times of Murshid Quli Khan. The English did not agree to the Nawab’s proposal rather they levied heavy duties on Indian goods entering Calcutta which was under their control. They also started fortifying their settlements against the order of the Nawab. All these amounted to a direct challenge to the Nawab’s Sovereignty. Shiraj-ud – Daulah in order to control the English activities and maintain the laws of the land seized the English Factory at Kasimbazar, marched on to Calcutta and occupied the Fort Williams in 1756 .As the Nawab went on to celebrate this easy victory of his, he made a mistake to underestimate the strength of his enemy. -

The Body, Subjectivity, and Sociality

THE BODY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIALITY: Fakir Lalon Shah and His Followers in Contemporary Bangladesh by Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder B.S.S in Sociology, University of Dhaka, 2002 M.A. in Sociology, University of Pittsburgh, 2011 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder It was defended on April 26, 2017 and approved by Lisa D Brush, PhD, Professor, Sociology Joseph S Alter, PhD, Professor, Anthropology Waverly Duck, PhD, Associate Professor, Sociology Mark W D Paterson, PhD, Assistant Professor, Sociology Dissertation Advisor: Mohammed A Bamyeh, PhD, Professor, Sociology ii Copyright © by Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder 2017 iii THE BODY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIALITY: FAKIR LALON SHAH AND HIS FOLLOWERS IN CONTEMPORARY BANGLADESH Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 I introduce the unorthodox conceptualization of the body maintained by the followers of Fakir Lalon Shah (1774-1890) in contemporary Bangladesh. This study is an exploratory attempt to put the wisdom of the Fakirs in conversation with established social theorists of the body, arguing that the Aristotelian conceptualization of habitus is more useful than Bourdieu’s in explaining the power of bodily practices of the initiates. My ethnographic research with the prominent Fakirs—participant observation, in-depth interview, and textual analysis of Lalon’s songs—shows how the body can be educated not only to defy, resist, or transgress dominant socio-political norms, but also to cultivate an alternative subjectivity and sociality. -

CHAPTER 4* EXPANSION of MARATHA POWER (1741—1761) BALAJI BAJI RAV Early Succees in the North

CHAPTER 4* EXPANSION OF MARATHA POWER (1741—1761) BALAJI BAJI RAV Early succees in the north. BAJI RAV DIED IN APRIL 1740 AND WAS SUCCEEDED in the Pesvaship by his son Balaji then twenty years old, The Chief Minister, by now, ruled in the Raja’s name the central region of Maharastra, north Konkan recently wrested from the Portuguese and levied cauth on Khandes, Malva, Bundelkhand and territories beyond. He commanded the largest army in the Maratha State and his resources were very great. This gave the Pesva family a preponderance in the Raja’s council and therefore the succession of the son to his father’s post was never in doubt. The story of the opposition of Raghuji Bhosle and Babuji Naik to the succession of Balaji Rav first accepted by Grant Duff and implicitly followed by later writers on the authority of Bakhars, appears to be an attempt made by the Pesva’s protagonists to defend his attack on the Nagpur Chief three years later and has little basis in fact. The succession of Balaji Baji Rav marked no ostensible change in-policy. The new Pesva indicated that he would follow his father’s expansionist policies in all respects and expressed his desire to maintain cordial relations with Rajput princes who had facilitated Maratha entry into Malva and their subsequent successes in Hindustan. The Nizam’s humiliating defeat at Bhopal (1738) had brought the whole of Malva under Maratha control, but the imperial grants which would put the seal of authority on the transfer had been delayed. Young Balaji, therefore, within four months of his investiture marched into Hindustan to renew friendly contacts with the Rajput Chiefs and undo the mischief created by the Nizam during his three years’ stay in the imperial capital. -

National Struggle from a Postcolonial Literary Perspective: Nuruldiner Sarajiban

The Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture.Vol 12.2.June 2019.29-52. DOI: 10.30395/WSR.201906_12(2).0002 National Struggle from a Postcolonial Literary Perspective: Nuruldiner Sarajiban Sabiha Huq ABSTRACT Leela Gandhi refers to Ranajit Guha’s opinion that Indian nationalism “achieves its entitlement through the systematic mobilization, regulation, disciplining and harnessing of subaltern energy, that nationalism integrates the randomly distributed energies of miscellaneous popular movements” (Dominance 144, qtd. in Gandhi 111). Syed Shamsul Haq (1935-2016), a literary stalwart of Bangladesh, has always been conscious of the contribution of the common rural people of Bangladesh to the nationalist cause. The mobilization of the peasants against British rule, as dramatized in Haq’s verse play Nuruldiner Sarajiban (1992), is one such movement, the systematic accumulation of which Guha terms as “subaltern” energy that culminates in anti- colonial nationalism in Bangladesh. Haq recreates the history of the Mughalhaat peasant insurgency of 1783 in Rangpur in his play in the 1990s, a specific juncture in the history of independent Bangladesh that requires the play to act as a clarion call to countrymen to unite against the then dictatorial government headed by Hussain Muhammad Ershad. The play simultaneously operates on two time frames: First, it establishes the position of the subaltern protagonist against the British colonizers that marks the postcolonial stance of the playwright, and then it stands as an inspirational symbol amidst its contemporary political crisis. The paper examines how the verse play illustrates both the colonial propaganda, the two-nation theory of the British colonial rule, and the anti-colonial agenda of the mass peasant movement— ascertaining Nuruldin’s position as a public hero, and also as an emissary of freedom and solidarity for all people in Bangladesh against neo-colonialism in a time of post-colony. -

Artuklu Human and Social Science Journal

Artuklu Human and Social Science Journal ARTICLE http://dergipark.gov.tr/itbhssj The Formation of Bengal Civilization: A Glimpse on the Socio-Cultural Assimilations Through Political Progressions Key words: in Bengal Delta 1. Bengal Delta Abu Bakar Siddiq1 and Ahsan Habib2 2. Socio-cultural Abstract assimilation The Bengal Delta is a place of many migrations, cultural transformations, invasions 3. Aryan and religious revolutions since prehistoric time. With the help of archaeological and historical records, this essay present the hypothesis that, albeit there were multiple 4. Mauryan waves of large and small scale socio-cultural assimilations, every socio-political 5. Medieval period change did not brought equal formidable outcome in the Delta. The study further illustrates that, the majority of cultural components were formulated by Indigenous- Aryan-Buddhist assimilations in early phase, whereas the Buddhist-Aryan-Islamic admixtures in relatively forbearing and gracious socio-political background of medieval period contributed the final part in the formation of Bengal Civilization. INTRODUCTION one of the most crowed human populations in the world The Bengal Delta (i.e. present Bangladesh and West with a density of more than 1100 people per square mile. Bengal in India) is the largest delta in the world (Akter The physiological features of Bengal delta is completely et al., 2016). Annual silt of hundreds of rivers together river based. River has tremendous effect on the with a maze of river branches all over this Green Delta formation of landscape, agriculture and other basic made it as one of the most fertile regions in the world. subsistence, trade and transport, as well as cultural Additionally, amazing landscape, profound natural pattern of its inhabitants. -

Society, Culture and Inter Communal Harmony During the Nawab Period (1727-1739) in Bengal

J.P.H.S., Vol. LXVII, Nos. 1 & 2 85 SOCIETY, CULTURE AND INTER COMMUNAL HARMONY DURING THE NAWAB PERIOD (1727-1739) IN BENGAL DR. SHOWKET ARA BEGUM Associate Professor Department of History, University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh. E-mail: Roshny Cu <[email protected]> It was a diverse society during the reign of Nawabs, consisting of people belonging to different religion, caste or creed. Murshid Quli Khan shifted the dewani from Dhaka to Murshidabad resulting in the transfer of the entire secretariat and court staff to the new place. Later when he was appointed Subahder of Bengal, Murshidabad was declared as the capital of Bengal. Immediately after the shifting of the capital, the whole royal staff, state officials and members of elite society settled down in Murshidabad. People from all walks of life thronged there for livelihood. Murshidabad, during the Nawabi period, turned into a rendezvous for people belonging to different sections of society. This tradition continued during the reign of Nawab Shujauddin Mohammad Khan (the successor of Nawab Murshid Quli Khan). Since hardly any objective material is available on the social history of Bengal during middle age, it is difficult to properly assess the social system prevailing during the reign of Nawab Shujauddin. Most of the eighteenth century sources of information are in Persian language including Siyar-ul-Mutakkherin by Ghulam Hossain Tabatabai, Riaz-us-salatin by Ghulam Hossain Salim, and Tarikh-i-Bangalah by Salimullah, Awal-e-Mahabbat Jang by Yousuf Ali and Muzaffarnamah by Karam Ali. Besides taking up help from history written in Pertsian language, 86 Society, culture and .. -

Pranab Mukherjee

www.theindianpanorama.com VOL 11 ISSUE 30 ● NEW YORK ● JULY 28 - AUGUST 03, 2017 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● PRICE 40 CENTS THE INDIAN PANORAMA 2 NEW YORK FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 International Indian Film Academy Show was a huge disappointment Impression of Patrons I.S. Saluja NEW YORK (TIP): "The biggest night of the year. A star-studded spectacle with the biggest Bollywood superstars! With extravagant productions and superbly choreographed performances, this magnificent evening honors the best talent in Indian Cinema. The evening will witness performances by Alia Bhatt, Katrina Kaif, Kriti Sanon, Salman Khan, Shahid Kapoor, Sushant Singh Rajput and more", read an announcement on IIFA website. The Bollywood loving Indian Americans were thrilled. They had the intense desire to meet with their idols and also they had the means to buy the most expensive tickets and they lined up, expecting to meet with their favorite stars and have a swell time at the IIFA extravaganza. But then, it was not to be. At including Matt Damon, Julia Roberts etc. written non entertaining script. Singers and ended up in the hospital. least, for many. It is hard to resist the temptation of and Star line up was good, but even then Wizcraft had lot of issues in Tampa, but The Indian Panorama received a couple of seeingSRK and Salmaan on the same Wizcraft managed toproduce a boring people took it as a first timer mistakes. letters describing IIFA as a hopeless and flop stage.But, the show had none of that. show for the most part. However, this repeated and deliberate attempt show, to be mild, and as a show meant to cheat This was a very cleverly done false and 5. -

District Handbook Murshidabad

CENSUS 1951 W.EST BENGAL DISTRICT HANDBOOKS MURSHIDABAD A. MITRA of the Indian Civil Service, Superintendent ot Census OPerations and Joint Development Commissioner, West Bengal ~ted by S. N. Guha Ray, at Sree Saraswaty Press Ltd., 32, Upper Circular Road, Calcutta-9 1953 Price-Indian, Rs. 30; English, £2 6s. 6<1. THE CENSUS PUBLICATIONS The Census Publications for West Bengal, Sikkim and tribes by Sudhansu Kumar Ray, an article by and Chandernagore will consist of the following Professor Kshitishprasad Chattopadhyay, an article volumes. All volumes will be of uniform size, demy on Dbarmapuja by Sri Asutosh Bhattacharyya. quarto 8i" x II!,' :- Appendices of Selections from old authorities like Sherring, Dalton,' Risley, Gait and O'Malley. An Part lA-General Report by A. Mitra, containing the Introduction. 410 pages and eighteen plates. first five chapters of the Report in addition to a Preface, an Introduction, and a bibliography. An Account of Land Management in West Bengal, 609 pages. 1872-1952, by A. Mitra, contajning extracts, ac counts and statistics over the SO-year period and Part IB-Vital Statistics, West Bengal, 1941-50 by agricultural statistics compiled at the Census of A. Mitra and P. G. Choudhury, containing a Pre 1951, with an Introduction. About 250 pages. face, 60 tables, and several appendices. 75 pages. Fairs and Festivals in West Bengal by A. Mitra, con Part IC-Gener.al Report by A. Mitra, containing the taining an account of fairs and festivals classified SubSidiary tables of 1951 and the sixth chapter of by villages, unions, thanas and districts. With a the Report and a note on a Fertility Inquiry con foreword and extracts from the laws on the regula ducted in 1950.