Struggles of Migrant Idol Makers in Pravachambalam: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coordinator, Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC)

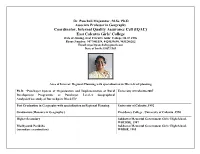

Dr. Panchali Majumdar, M.Sc, Ph.D Associate Professor in Geography Coordinator, Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) East Calcutta Girls’ College Date of Joining, East Calcutta Girls’ College: 01.07.1996 Phone Number: 9477001138, 8420539690, 9433246262 Email:[email protected] Date of birth:19.07.1969 Area of Interest: Regional Planning with specialization in Micro-level planning Ph.D: “Panchayet System of Organisation and Implementation of Rural University of Calcutta,2007 Development Programme at Panchayet Level-A Geographical Analysis(Case study of Barrackpore Block II)” Post Graduation in Geography with specialization in Regional Planning University of Calcutta ,1992 Graduation (Honours in Geography ) Presidency College , University of Calcutta ,1990 Higher Secondary Sakhawat Memorial Government Girls’ High School, WBCHSE, 1987 Madhyamik Pariksha Sakhawat Memorial Government Girls’ High School, (secondary examination) WBBSE, 1985 Other Awarded as NSS CO-ORDINATOR Governing Member of Post Graduate Board of Studies, Activities Programme Officer Internal Quality Body East Calcutta Girls’ College. Invitee member Assurance Cell (IQAC) member for of UG BOS , Burdwan University,2018.Acted for 2012-2013,2013- three(3) term East Calcutta Girls’ as Editorial Board Member in ,Environment 14, 2014-2015 period. College from 2015. Acted as and Sustainability-A Geographical Incharge of Perspective, ISBN:978-93-83010-29-5,2016. Member of IQAC, ECGC the College on from2010. 06.04.2016, 20.04.2016, 15.6.2017 to 16.06.2017, 30.8.17 to 16.09.2017. Teaching Acted as Head Examiner, Taking regular classes in Invited in Post Graduate studies (regular ) in Experience Moderator, Examiner , Post Graduate course Ashutosh College from 2011 to 2019, Barrackpore Scrutineer, Paper Setter in (Regular), in East Calcutta Rastraguru Surendranath College from 2014 to Unergraduate and Post Girls’ College 2018. -

Paper Code: Dttm C205 Tourism in West Bengal Semester

HAND OUT FOR UGC NSQF SPONSORED ONE YEAR DILPOMA IN TRAVEL & TORUISM MANAGEMENT PAPER CODE: DTTM C205 TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL SEMESTER: SECOND PREPARED BY MD ABU BARKAT ALI UNIT-I: 1.TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL: AN OVERVIEW Evolution of Tourism Department The Department of Tourism was set up in 1959. The attention to the development of tourist facilities was given from the 3 Plan Period onwards, Early in 1950 the executive part of tourism organization came into being with the appointment of a Tourist Development Officer. He was assisted by some of the existing staff of Home (Transport) Department. In 1960-61 the Assistant Secretary of the Home (Transport) Department was made Director of Tourism ex-officio and a few posts of assistants were created. Subsequently, the Secretary of Home (Transport) Department became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Two Regional Tourist Offices - one for the five North Bengal districts i.e., Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, West Dinajpur and Maida with headquarters at Darjeeling and the other for the remaining districts of the State with headquarters at Kolkata were also set up. The Regional Office at KolKata started functioning on 2nd September, 1961. The Regional Office in Darjeeling was started on 1st May, 1962 by taking over the existing Tourist Bureau of the Govt. of India at Darjeeling. The tourism wing of the Home (Transport) Department was transferred to the Development Department on 1st September, 1962. Development. Commissioner then became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Subsequently, in view of the increasing activities of tourism organization it was transformed into a full-fledged Tourism Department, though the Secretary of the Forest Department functioned as the Secretary, Tourism Department. -

Pranab Mukherjee

www.theindianpanorama.com VOL 11 ISSUE 30 ● NEW YORK ● JULY 28 - AUGUST 03, 2017 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● PRICE 40 CENTS THE INDIAN PANORAMA 2 NEW YORK FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 International Indian Film Academy Show was a huge disappointment Impression of Patrons I.S. Saluja NEW YORK (TIP): "The biggest night of the year. A star-studded spectacle with the biggest Bollywood superstars! With extravagant productions and superbly choreographed performances, this magnificent evening honors the best talent in Indian Cinema. The evening will witness performances by Alia Bhatt, Katrina Kaif, Kriti Sanon, Salman Khan, Shahid Kapoor, Sushant Singh Rajput and more", read an announcement on IIFA website. The Bollywood loving Indian Americans were thrilled. They had the intense desire to meet with their idols and also they had the means to buy the most expensive tickets and they lined up, expecting to meet with their favorite stars and have a swell time at the IIFA extravaganza. But then, it was not to be. At including Matt Damon, Julia Roberts etc. written non entertaining script. Singers and ended up in the hospital. least, for many. It is hard to resist the temptation of and Star line up was good, but even then Wizcraft had lot of issues in Tampa, but The Indian Panorama received a couple of seeingSRK and Salmaan on the same Wizcraft managed toproduce a boring people took it as a first timer mistakes. letters describing IIFA as a hopeless and flop stage.But, the show had none of that. show for the most part. However, this repeated and deliberate attempt show, to be mild, and as a show meant to cheat This was a very cleverly done false and 5. -

Secret & Sacred Embodiment of Goddess Durga Idol

Man In India, 9996 (1-2)(12) : : 5 151-155747-5751 © Serials Publications SECRET & SACRED EMBODIMENT OF GODDESS DURGA IDOL Sourav Mohanty* and Chandrabhanu Das** A festival, which unleashes the ‘Shakti’ by Goddess Durga over the Demon God ‘Mahisaasura’ to win the good over the evil. Manifestation of Goddess Durga is done as we plunge into the secret and sacred ways of making the idol of Goddess Durga ready before the puja commences. Purpose: The article highlights about the mysterious and tenebrous side of formation of Goddess Durga idol during Durga Puja. Design/Methodology: It is a descriptive review where the difficulties and hindrances are highlighted as far as Goddess Durga idol formation is concerned. Research Limitations: Lack of empirical data and the study is limited to theoretical aspects. Practical Implications: Implied to age old traditional customs, belief which is still practiced in Bengal and some parts of Assam. Originality: This is the authentic paper looking at Goddess Durga idol formation theoretically in religious aspects. Keywords: Goddess Durga, Idol, Punya mati Paper Type: General Review. Overview Shaktism and Tantrism are the two opposite sides of the same coin. Shaktism is quite evidently seen to be practiced in all parts of Bengal and North East, especially Assam. Shakti here refers to ‘Shakti’ or the divine power which is derived from the from Indian Goddess like Devi or Kali or Durga.The cult of Hinduism where the female goddess is being worshipped and adored is known as Shaktism. (Rukmani, 2016) Shaktism itself embodies Shaivism. This Shaivism has two aspects mainly- one its specialists (who preach Shaktism called shaktas) lay more significance on the benediction of Supreme Divine Shiva (Effeminate aspect) and macho aspect of deific is utilized mainly to be preeminence where the manifestation of an almighty’s drift and dynamism is not influenced by any surroundings or by any physical laws. -

Indian Water Works Association 47Th IWWA Annual Conven On, Kolkata

ENTI NV ON O 2 0 C 1 L 5 A , K U Indian Water Works O N L N K A A h T t A 7 Association 4 47th Annual Convention Kolkata 30th, 31st Jan & 1st Feb, 2015 Theme: ‘Sustainable Technology Soluons for Water Management’ Venue: Science City J.B.S Haldane Avenue Kolkata ‐ 700046, (West Bengal) Convention Hosted By IWWA Kolkata Centre INDIAN WATER WORKS ASSOCIATION 47th IWWA ANNUAL CONVENTION, KOLKATA Date : 30th, 31st January & 1st February, 2015 Venue : Science City, J.B.S Haldane Avenue, Kolkata ‐ 700046, West Bengal APPEAL Dear sir, The Indian Water Works Associaon (IWWA) is a voluntary body of professionals concerned and connected with water supply for rural, urban, industrial, agricultural uses and disposal of wastewater. IWWA focuses basically on the enre 'Water Cycle' encompassing the environmental, social, instuonal and financial issues in the area of water supply, wastewater treatment & disposal. IWWA was founded in the year 1968 with headquarters at Mumbai having 32 centers across the country with more than 9000 members from all professions around the world. The Kolkata Centre of IWWA in associaon with Public Health Engineering Department, Govt. of West Bengal along with others is organizing The 47th IWWA Convenon in Kolkata from 30th January to 1st February, 2015 at Science City, J.B.S Haldane Avenue, Kolkata ‐ 700046, West Bengal under the Theme 'Sustainable Technology Soluons for Water Management'. The professionals from all over the country and abroad will parcipate and present their technical papers in the three days convenon. The organizing commiee would like to showcase the Kolkata convenon in a very meaningful manner and make it a grand success and a memorable event to be cherished for a long me. -

CONCEIVING the GODDESS an Old Woman Drawing a Picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a Village Wall, Gujrat State, India

CONCEIVING THE GODDESS An old woman drawing a picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a village wall, Gujrat State, India. Photo courtesy Jyoti Bhatt, Vadodara, India. CONCEIVING THE GODDESS TRANSFORMATION AND APPROPRIATION IN INDIC RELIGIONS Edited by Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions © Copyright 2017 Copyright of this collection in its entirety belongs to the editors, Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett. Copyright of the individual chapters belongs to the respective authors. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building, 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/cg-9781925377309.html Design: Les Thomas. Cover image: The Goddess Sonjai at Wai, Maharashtra State, India. Photograph: Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat. ISBN: 9781925377309 (paperback) ISBN: 9781925377316 (PDF) ISBN: 9781925377606 (ePub) The Monash Asia Series Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions is published as part of the Monash Asia Series. The Monash Asia Series comprises works that make a significant contribution to our understanding of one or more Asian nations or regions. The individual works that make up this multi-disciplinary series are selected on the basis of their contemporary relevance. -

Withwings All the Best Instagram Accounts Have Wings

withWings all the best instagram accounts have wings get more instagram followers with the best social media agency on the block 7-day free trial. cancel anytime. open access we are primarily creating this database of location ids for our own ease of access, and for use in our internal client targeting. At withwings, however, we pride ourselves on the principle that sharing really is caring. we created our managed instagram growth services so that we could share our success with others, and so, supporting others is one of our greatest moral prides. about instagram location identifications what is an instagram location id? an instagram location id is a number (used as a catalogue number in a url slug) which links to a collection of instagram posts that were posted from a specific location. there are thousands upon thousands of these locations on instagram, each with their own post count. a location is either chosen manually by the poster, or automatically by instagram when it reads a user's posting location. who can benefit from a location id list? whether you're looking to explore a certain location on instagram or help your social media manager find the best targeting for your instagram growth package, you can benefit from this list, as it's easy to navigate and filter through in programs like microsoft excel. what does a list include? we only included the information that we felt would be the most usable for others, and easy to navigate. this includes: • the location id url slug • the location identification number • the location name, and; • the post count in that location on the day of extraction how to use this database if you’re not sure how to use this data – read our knowledge base article: ‘how do i use your location id database’. -

Kolkata Train

Here is the complete history of Kolkata tram routes, from 1873 to 2020. HORSE TRAM ERA 1873 – Opening of horse tram as meter gauge, closure in the same year. 1880 – Final opening of horse tram as a permanent system. Calcutta Tramways Company was established. 1881 – Dalhousie Square – Lalbazar - Bowbazar – Lebutala - Sealdah Station. (Later route 14) Esplanade – Lalbazar – Pagyapatti – Companybagan - Shobhabazar - Kumortuli. (Later route 7 after extension) Dalhousie Square – Esplanade. (Later route 22, 24, 25 & 29) Esplanade – Planetarium - Hazra Park - Kalighat. (Later route 30) 1882 - Esplanade – Wellington Square – Bowbazar – Boipara - Hatibagan - Shyambazar Junction. (Later route 5) Wellington Square – Moula Ali - Sealdah Station. (Later route 12 after extension) Dalhousie Square – Metcalfe Hall - High Court. (Later route 14 extension) Metcalfe Hall – Howrah Bridge - Nimtala. (Later route 19). Steam tram service was thought. STEAM TRAM ERA 1883 - Esplanade – Racecourse - Wattganj - Khidirpur. (Later route 36) 1884 - Wellington Square – Park Street. (Later route 21 & 22 after extension) 1900 - Nimtala – Companybagan (non-revenue service only). Electrification & conversion to standard gauge was started. ELECTRIC TRAM ERA 1902 - Khidirpur & Kalighat routes were electrified. Shobhabazar – Hatibagan. (Later route 9 & 10) Nonapukur Workshop opened with Royd Street – Nonapukur (Later route 21 & 22 after re-extension). Royd Street – Park Street closed. 1903 – Shyambazar terminus opened with Shyambazar – Belgachhia. (Later route 1, 2, 3, 4 & 11) Kalighat – Tollyganj. (Later route 29 & 32) 1904 - Kumortuli – Bagbazar. Kumortuli terminus closed. (Later route 7 & 8) 1905 - Howrah Bridge – Pagyapatti – Boipara – Purabi Cinema - Sealdah Station (Later route 15). All remaining then-opened routes were electrified. 1907 - Moula Ali – Nonapukur. (Later route 20 & 26 after extension) Wattganj – Mominpur (via direct access through Ofphanganjbazar). -

(IHWF) 2019, Unavailable, Such As Children, the Differently- Into a Conversation About Heritage

INDIA HERITAGE WALK FESTIVAL FEBRUARYFEBRUARY 20192019 FEBRUARY 2019 CONTENTS 24.02 | Art Deco at the Oval Walk, Mumbai About the walk i Foreword ii Preface iv 1. Event Statistics 1 2. Event Schedule 3 3. Walk Leaders, Speakers, and Facilitators 19 4. Giveaways 23 5. Social Media Engagement 25 6. Coverage 27 7. Partners 29 8. Festival Team 31 24.02 | It All Started with the Big Bang: A 17.02 | The British Calcutta and World Walk through the Natural Museum, War II, Kolkata Chandigarh 37 cities and 114 events across the country. also brought into its fold global audiences, The programme was curated thematically— through social media activity fora. ranging from museums, historically significant FOREWORD We are glad that the second edition of the ABOUT monuments and markets, to explorations of festival has generated deeper interest about interesting natural landscapes and areas Indian culture, while discovering new ways of known for their rich cuisine, and women- The present is a gift of the past. Our cultural exploring and appreciating it. Enthusiastic oriented narratives. The focus was on heritage defines our identities, and is pivotal involvement by people across the country is encouraging and increasing different forms of in connecting communities. The India proof of the fact that there is a need to engage engagement with important heritage spaces, Heritage Walk Festival was initiated by more actively with our cultural pasts in the while also ensuring that these heritage spaces Sahapedia to enable enthusiasts to delve contemporary scenario. were made accessible to various audience deeper into the broad and diverse spectrum groups. -

Bichitra Inc. 2016

Bichitra Inc. 2016 1 Platinum Sponsor 2 From the President’s Desk Dear Bichitra Inc. family, On behalf of Bichitra Inc. executive committee I welcome you to Durga Puja 2016. It is the event we all wait for every year to not only celebrate the victory of good over evil but also to meet members of our family over 3 days, adda to- gether, worshipping together, eating together, enjoying the cultural activities and dancing to dhak beats together. This feeling of family is what makes Bichitra Inc special. On this joyous occasion I dedicate this Rabindra Sangeet 'Amar Hiyar Majhei lukiye chhile' to our family. This year the highlights of our Pujo are a new Durga Protima, the band Kaya from Kolkata, Dhunuchi Naach competition and of course our local talent perform- ing. Hoping all family members have a joyous 3 days and seeking in advance for- giveness for any errors of commission or omission. This 3 day celebration has been made possible due to the participation and contributions of each family member. I salute you for your dedication to our family. I thank each corporate sponsor whose generous support has gone a long way in making this celebration feasible. And finally my executive committee and all the volunteers. Through your untiring efforts you once again have brought this joyful celebration to the family. Amidst all this joy I would like all of us to reflect on the loss of our very dear family member Avik Guha and pray for his soul the very fundamental of our existence. May God bring peace to the family. -

Kolkata...The City Of

Kolkata .... the city of Joy Kolkata- The Capital city, popularly known as The 'City of Joy'. The city is dipped in history, art & culture, sports and socio-cultural activities. This was the erstwhile capital of the British Raj, and thus has architectural gems strewn all around. The city has its appeal for all visitors, with a medley of interest. From architectural wonders to swanky malls, from religious places to centres for performing arts, from historical colleges & universities to state-of-the-art stadiums. Attractions & Tours Kolkata, formerly known as Calcutta in English, is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal and is located in eastern India on the east bank of the River Hooghly. The city was a colonial city developed by the British East India Company and then by the British Empire. Kolkata was the capital of the British Indian empire until 1911 when the capital was relocated to Delhi. Kolkata grew rapidly in the 19th century to become the second city of the British Empire. This was accompanied by the development of a culture that fused European philosophies with Indian tradition. During the British colonial era from 1700 to 1912 Kolkata was the capital of British India. Kolkata witnessed a spate of frenzied construction activity in the early 1850s by several British companies. The construction was largely influenced by the conscious intermingling of Neo-Gothic, Baroque, Neo- Classical, and Oriental designs. Unlike many north Indian cities, whose construction stresses minimalism, much of the layout of the architectural variety in Kolkata owes its origins from European styles and tastes imported mainly by the British, and lesser extent of the Portuguese and French. -

Updating Mapping & Size Estimation for Core Groups at Risk of HIV/AIDS

FINAL REPORT Updating Mapping and Size Estimation for Core Groups at Risk of HIV/AIDS in West Bengal Commissioned by West Bengal State AIDS Prevention and Control Society Quest Asia Flat GA1, 201 Jodhpur Park Kolkata 700 068 Final Report: Updating Mapping and Size Estimation for Core Groups at Risk of HIV/AIDS in West Bengal Prepared for West Bengal State AIDS Prevention and Control Society March 2007 A Study Conducted by Quest Asia, Flat GA1, 201 Jodhpur Park, Kolkata 700068. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 1 I INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................................. 9 1.0 BACKGROUND................................................................................................................................................ 9 1.1 NEED FOR MAPPING EXERCISE .................................................................................................................... 10 1.2 SCOPE OF THE MAPPING EXERCISE ............................................................................................................... 10 1.3 OBJECTIVES OF THE PRESENT STUDY ........................................................................................................... 11 II METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................