Jamaican Creole in Moss Side

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Exploring the potential of complexity theory in urban regeneration processes. MOOBELA, Cletus. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20078/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20078/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Fines are charged at 50p per hour JMUQ06 V-l 0 9 MAR ?R06 tjpnO - -a. t REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10697385 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697385 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Exploring the Potential of Complexity Theory in Urban Regeneration Processes Cletus Moobela A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The carrying out and completion of this research project was a stimulating experience for me in an area that I have come to develop an ever-increasing amount of personal interest. -

14-1676 Number One First Street

Getting to Number One First Street St Peter’s Square Metrolink Stop T Northbound trams towards Manchester city centre, T S E E K R IL T Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale S M Y O R K E Southbound trams towardsL Altrincham, East Didsbury, by public transport T D L E I A E S ST R T J M R T Eccles, Wythenshawe and Manchester Airport O E S R H E L A N T L G D A A Connections may be required P L T E O N N A Y L E S L T for further information visit www.tfgm.com S N R T E BO S O W S T E P E L T R M Additional bus services to destinations Deansgate-Castle field Metrolink Stop T A E T M N I W UL E E R N S BER E E E RY C G N THE AVENUE ST N C R T REE St Mary's N T N T TO T E O S throughout Greater Manchester are A Q A R E E S T P Post RC A K C G W Piccadilly Plaza M S 188 The W C U L E A I S Eastbound trams towards Manchester city centre, G B R N E R RA C N PARKER ST P A Manchester S ZE Office Church N D O C T T NN N I E available from Piccadilly Gardens U E O A Y H P R Y E SE E N O S College R N D T S I T WH N R S C E Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale Y P T EP S A STR P U K T T S PEAK EET R Portico Library S C ET E E O E S T ONLY I F Alighting A R T HARDMAN QU LINCOLN SQ N & Gallery A ST R E D EE S Mercure D R ID N C SB T D Y stop only A E E WestboundS trams SQUAREtowards Altrincham, East Didsbury, STR R M EN Premier T EET E Oxford S Road Station E Hotel N T A R I L T E R HARD T E H O T L A MAN S E S T T NationalS ExpressT and otherA coach servicesO AT S Inn A T TRE WD ALBERT R B L G ET R S S H E T E L T Worsley – Eccles – -

Hulme, Moss Side and Rusholme Neighbourhood Mosaic Profile

Hulme, Moss Side and Rusholme Neighbourhood Mosaic Profile Summary • There are just over 21,300 households in the Hulme, Moss Side and Rusholme Neighbourhood. • The neighbourhood contains a range of different household types clustered within different parts of the area. Moss Side is dominated by relatively deprived, transient single people renting low cost accommodation whereas Hulme and Rusholme wards contain larger concentrations of relatively affluent young people and students. • Over 60% of households in Moss Side contain people whose social circumstances suggest that they may need high or very high levels of support to help them manage their own health and prevent them becoming high users of acute healthcare services in the future. However, the proportion of households in the other parts of the neighbourhood estimated to require this levels of support is much lower. This reflects the distribution of different types of household within the locality as described above. Introduction This profile provides more detailed information about the people who live in different parts of the neighbourhood. It draws heavily on the insights that can be gained from the Mosaic population segmentation tool. What is Mosaic? Mosaic is a population segmentation tool that uses a range of data and analytical methods to provide insights into the lifestyles and behaviours of the public in order to help make more informed decisions. Over 850 million pieces of information across 450 different types of data are condensed using the latest analytical techniques to identify 15 summary groups and 66 detailed types that are easy to interpret and understand. Mosaic’s consistent segmentation can also provide a ‘common currency’ across partners within the city. -

Whalley Range and Around Key

Edition Winter 2013/14 Winter Edition 2 nd Things about Historical facts, trivia and other things of interest Alexandra Park Manley Hall Primitive Methodist College The blitz 1 9 Wealthy textile merchant 12 Renamed Hartley Victoria College after its 16 The bombs started dropping on The beginning: Designed Samuel Mendel built a 50 benefactor Sir William P Hartley, was opened in Manchester during Christmas 1940 with by Alexander Hennell and the Range room mansion in the 1879 to train men to be religious ministers. homes in the Manley Park area taking opened in 1870, the fully + MORE + | CLUBS SPORTS | PARKS | SCHOOLS | HISTORY | LISTINGS | TRIVIA 1860s, with extensive Now known as Hartley Hall, it is an several direct hits. Terraced houses in public park (named after gardens running beyond independent school. Cromwell Avenue were destroyed and are Princess Alexandra) was an Bury Avenue and as far as noticeable by the different architecture. During oasis away from the smog PC Nicholas Cock, a murder Clarendon Road (pictured air raids people would make their way to a of the city and “served to 13 In the 1870s a policeman was fatally wounded left). Mendel’s business shelter, one of which was (and still is!) 2.5m deter the working men whilst investigating a disturbance at a house collapsed when the Suez under Manley Park and held up to 500 people. of Manchester from the near to what was once the Seymour Hotel. The Origins: Whalley Range was one of Manchester’s, and in fact Canal opened and he was The entrance was at the corner of York Avenue alehouses on their day off”. -

Q05a 2011 Census Summary

Ward Summary Factsheet: 2011 Census Q05a • The largest ward is Cheetham with 22,562 residents, smallest is Didsbury West with 12,455 • City Centre Ward has grown 156% since 2001 (highest) followed by Hulme (64%), Cheetham (49%), Ardwick (37%), Gorton South (34%), Ancoats and Clayton (33%), Bradford (29%) and Moss Side (27%). These wards account for over half the city’s growth • Miles Platting and Newton Heath’s population has decreased since 2001(-5%) as has Moston (-0.2%) • 81,000 (16%) Manchester residents arrived in the UK between 2001 and 2011, mostly settling in City Centre ward (33% of ward’s current population), its neighbouring wards and Longsight (30% of current population) • Chorlton Park’s population has grown by 26% but only 8% of its residents are immigrants • Gorton South’s population of children aged 0-4 has increased by 87% since 2001 (13% of ward population) followed by Cheetham (70%), Crumpsall (68%), Charlestown (66%) and Moss Side (60%) • Moss Side, Gorton South, Crumpsall and Cheetham have around 25% more 5-15 year olds than in 2001 whereas Miles Platting and Newton Heath, Woodhouse Park, Moston and Withington have around 20-25% fewer. City Centre continues to have very few children in this age group • 18-24 year olds increased by 288% in City Centre since 2001 adding 6,330 residents to the ward. Ardwick, Hulme, Ancoats and Clayton and Bradford have also grown substantially in this age group • Didsbury West has lost 18-24 aged population (-33%) since 2001, followed by Chorlton (-26%) • City Centre working age population has grown by 192% since 2001. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future. A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/12v9d1gx Author Marcus, Nicole Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance by Nicole Elise Marcus A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gary Holland, Chair Professor Leanne Hinton Professor Johanna Nichols Fall 2010 The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance © 2010 by Nicole Elise Marcus Abstract The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance by Nicole Elise Marcus Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gary Holland, Chair The énonciatif system is a defining linguistic feature of Gascon, an endangered Romance language spoken primarily in southwestern France, separating it not only from its neighboring Occitan languages, but from the entire Romance language family. This study examines this preverbal particle system from a diachronic and synchronic perspective to shed light on issues of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance. The diachronic source of this system has important implications regarding its current and future status. My research indicates that this system is an ancient feature of the language, deriving from contact between the original inhabitants of Gascony, who spoke Basque or an ancestral form of the language, and the Romans who conquered the region in 56 B.C. -

Children's Community Health Services

Children’s Community Health Services Quick Facts Document Content Service Vision ……..………………………………………………………………………………..Page 3 Children and young person’s health service……………………………………………Page 5 Management Structure……………………………………………………………………Page 6 Universal services Health Visiting ……………………………………………………………………………..Page 7 School Health………………………………………………………………………………Page 8 Healthy Schools……………………………………………………………………………Page 9 Immunisation Team………………………………………………………………………..Page 10 Newborn Hearing Screening Programme……………………………………………....Page 11 Specialist Services Audiology …………………………………………………………………………………..Page 12 Community Children’s Nursing Team……………………………………………………Page 13 Physiotherapy……………………………………………………………………………...Page 14 Speech and Language Therapy………………………………………………………….Page 15 Orthoptics …………………………………………………………………………………..Page 15 Community Paediatrics…………………………………………………………………....Page 16 Occupational Therapy …………………………………………………………………….Page 17 Special Needs School Nursing and Dietetics…………………………………………...Page 17 Vulnerable Baby Service………………………………………………………………….Page 18 Child Health ………………………………………………………………………………..Page 18 Page 2 Children’s Community Health Services Directorate Strategy 2015 – 2019 1.0 Vision Our vision for Children’s Community Health Services is for every child in Manchester to have the best health possible. Our strapline, which will appear on our e-mails, is: “Working together to enable every child to have the best health possible” 1.1 We will aim to achieve our vision by: Delivering services which meet the health needs of children and -

Hulme, Moss Side & Rusholme Neighbourhood Update 12

Hulme, Moss Side and Rusholme Neighbourhood update 12th June 2020 As a Neighbourhood we are working together to make sure that key information is shared, to support the people most at risk during this time. Click on the web links embedded below for further info. Please let me know if there’s any gaps in info needed at a Neighbourhood level, or any gaps or patterns that you are finding with the people you work with, or other relevant info to share. If you have concerns that someone may be most at risk, please contact: ● Care Navigator Service: self-referrals possible via email (referrals from organisations also by phone, 0300 303 9650); for people dealing with more complex issues; multi-agency approach. ● Be Well: referrals and social prescribing via any organisation & GPs; email or 0161-470 7120. ● Manchester City Council’s Community Response helpline: 0800 234 6123 or email. Mutual aid groups and volunteering ● Covid mutual aid groups are coordinating invaluable support at a local level for neighbours by neighbours. Info, support & guidance is available here and here. Manchester map of local mutual aid groups ● Mutual aid group organiser/admin? Share learning, ask & answer questions to other organisers. ● Public sector organisation looking for volunteers? Register needs with MCRVIP, or volunteer. ● 2,600 Manchester volunteers ready for your VCSE group or organisation - what do you need? Request or offer support. Support on managing volunteers, capacity-building & more. Social isolation and mental health ● The Resonance Centre is offering 12 free classes every week on Zoom, suitable for beginners and designed to help people with physical wellbeing and mental health - Yin and Vinyasa Yoga, Meditation, Pranayama, Art, plant-based cooking, and more. -

Geddie 1 the USE of OCCITAN DIALECTS in LANGUEDOC

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Mississippi Geddie 1 THE USE OF OCCITAN DIALECTS IN LANGUEDOC-ROUSSILLON, FRANCE By Virginia Jane Geddie A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Oxford May 2014 Approved by _______________________________ Advisor: Professor Allison Burkette _______________________________ Reader: Professor Felice Coles _______________________________ Reader: Professor Robert Barnard Geddie 1 Abstract Since the medieval period, the Occitan dialects of southern France have been a significant part of the culture of the Midi region of France. In the past, it was the language of the state and literature. However, Occitan dialects have been in a slow decline, beginning with the Ordinance of Villers-Coterêts in 1539 which banned the use of Occitan in state affairs. While this did little to affect the daily life and usage of Occitan, it established a precedent that is still referred to in modern arguments about the use of regional languages (Costa, 2). In the beginning of the 21st century, the position of Occitan dialects in Midi is precarious. This thesis will investigate the current use of Occitan dialects in and around Montpellier, France, particularly which dialects are most commonly used in the region of Languedoc-Roussillon (where Montpellier is located), the environment in which they are learned, the methods of transmission, and the general attitude towards Occitan. It will also discuss Occitan’s current use in literature, music, and politics. While the primary geographic focus of this thesis will be on Montpellier and its surroundings, it should somewhat applicable to the whole of Occitan speaking France. -

Exploring Occitan and Francoprovençal in Rhône-Alpes, France Michel Bert, Costa James

What counts as a linguistic border, for whom, and with what implications? Exploring Occitan and Francoprovençal in Rhône-Alpes, France Michel Bert, Costa James To cite this version: Michel Bert, Costa James. What counts as a linguistic border, for whom, and with what implications? Exploring Occitan and Francoprovençal in Rhône-Alpes, France. Dominic Watt; Carmen Llamas. Language, Borders and Identity, Edinburgh University Press, 2014, Language, Borders and Identity, 0748669779. halshs-01413325 HAL Id: halshs-01413325 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01413325 Submitted on 9 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. What counts as a linguistic border, for whom, and with what implications? Exploring Occitan and Francoprovençal in Rhône-Alpes, France Michel Bert (DDL, Université Lumière/Lyon2) [email protected] James Costa (ICAR, Institut français de l’éducation/ENS de Lyon) [email protected] 1. Introduction Debates on the limits of the numerous Romance varieties spoken in what was once the western part of the Roman Empire have been rife for over a century (e.g. Bergounioux, 1989), and generally arose in the context of heated discussions over the constitution and legitimation of Nation-states. -

Indo-Caribbean African-Isms

Indo-Caribbean African-isms: Blackness in Guyana and South Africa By Andre Basheir A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Andre Basheir 2013 ii Indo-Caribbean African-ism: Blackness in Guyana and South Africa Master of Arts, 2013 Andre Basheir, Sociology and Equity Studies in Education, University of Toronto Abstract In an attempt to close the gaps between diaspora and regional studies an Afro-Asian comparative perspective on African and Indian identity will be explored in the countries of Guyana and South Africa. The overlying aim of the ethnographic research will be to see whether blackness can be used as a unifier to those belonging to enslaved and indentured diasporas. Comparisons will be made between the two race models of the Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean worlds. A substantial portion will be set aside for a critique of the concept of Coolitude including commentary on V.S. Naipaul. Further, mixing, creolization, spirituality and the cultural politics of Black Consciousness, multiculturalism, and dreadlocks will be exemplified as AfroAsian encounters. iii Acknowledgements Firstly, I like to thank all the people in the areas I conducted my fieldwork (South Africa especially). I befriend many people who had enormous amounts of hospitality. Specifically, Mark, Bridgette and family as well as Omar, Pinky and Dr. Naidoo and family for letting me stay with them and truly going out of their way to help my research efforts. Many thanks goes to a large list of others that I interviewed. -

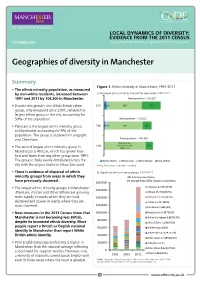

Geographies of Diversity in Manchester

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Manchester Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Manchester, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased between a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 1991 and 2011 by 104,300 in Manchester. Total population – 503,127 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 5% 2% 59% 33% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city, accounting for 59% of the population. Total population – 422,922 • Pakistani is the largest ethnic minority group 2001 2% 4% 74% 19% in Manchester accounting for 9% of the population. The group is clustered in Longsight and Cheetham. Total population – 432,685 85% (includes 1991 White Other and 15% • The second largest ethnic minority group in White Irish Manchester is African, which has grown four- fold and faster than any other group since 1991. The group is fairly evenly distributed across the White Other White Irish White British Non-White city with the largest cluster in Moss Side ward. Notes: Figures may not add due to rounding. • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 minority groups from areas in which they 2011 Census estimates (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. 180,000 • The largest ethnic minority groups in Manchester Pakistani 42,904 (73%) 160,000 (Pakistani, African and Other White) are growing African 25,718 (254%) more rapidly in wards where they are least 140,000 Chinese 13,539 (142%) clustered and slower in wards where they are Indian 11,417 (80%) 120,000 most clustered.