Land Management Plan from the Maidu Summit Consortium (2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seriating Arrow Points from Dart Points Subdivide the Study Area Into Seven Sub-Regions Depicted in Figure 1

PREHISTORY CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 103 SSSPPPAAATIALTIALTIAL ANDANDAND TEMPORALEMPORALEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION OFOFOF ROSEOSEOSE SPRINGPRINGPRING PROJECTILEROJECTILEROJECTILE POINTSOINTSOINTS INININ THETHETHE NORTHORTHORTH-C-C-CENTRALENTRALENTRAL SIERRAIERRAIERRA NEVEVEVADAADAADA RICHARD W. DEIS Rose Spring corner-notched projectile points have been used within the North-Central Sierra Nevada region primarily to date surface assemblages, in an attempt to develop temporal affinities between sites and to trace technological innovation (i.e. introduction of the bow and arrow). Temporal placements have primarily been based upon projectile point cross-dating using typologies established for the Great Basin, without regard for a demonstrated link to this region of study. This paper presents the results of analysis that addressed the utility of Rose Spring corner-notched points as temporal markers, and presents implications for the results of this study. ose Spring corner-notched projectile points Rivers) which are located along the eastern margin of have been used within the North-Central the project area. RSierra Nevada region to date surface assemblages, in an attempt to develop temporal affinities between sites and to trace technological TYPE CONCEPT AND innovation, i.e. introduction of the bow and arrow. DEVELOPMENT OF TYPOLOGIES Temporal placements have primarily been based upon projectile point cross-dating using typologies Definitions of types used in this study are established for the Great Basin, without regard for a according to Steward (1954) who defined these in demonstrated link within the study region. terms of morphology, historical significance, functional traits or cultural characteristics. This paper briefly summarizes more extensive Morphological types are the most basic and consist of research presented in an MA thesis of the same title descriptions of form or visually observed (Deis 1999). -

August 24, 2020—5:00 P.M

BUTTE COUNTY FOREST ADVISORY COMMITTEE August 24, 2020—5:00 P.M. Meeting via ZOOM Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89991617032?pwd=SGYzS3JYcG9mNS93ZjhqRkxSR2o0Zz09 Meeting ID: 899 9161 7032 Passcode: 300907 One tap mobile +16699006833,,89991617032# US (San Jose) +12532158782,,89991617032# US (Tacoma) Dial by your location +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) Meeting ID: 899 9161 7032 ITEM NO. 1.00 Call to order – Butte County Public Works Facility, Via ZOOM 2.00 Pledge of allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America 2.01 Roll Call – Members: Nick Repanich, Thad Walker, Teri Faulkner, Dan Taverner, Peggy Moak (Puterbaugh absent) Alternates: Vance Severin, Carolyn Denero, Bob Gage, Holly Jorgensen (voting Alt), Frank Stewart Invited Guests: Dan Efseaff,(Director, Paradise Recreation and Park District); Dave Steindorf (American Whitewater); Jim Houtman (Butte County Fire Safe Council); Taylor Nilsson (Butte County Fire Safe Council), Deb Bumpus (Forest Supervisor, Lassen National Forest); Russell Nickerson,(District Ranger, Almanor Ranger District, Lassen National Forest); Chris Carlton (Supervisor, Plumas National Forest); David Brillenz (District Ranger, Feather River Ranger District (FRRD), Plumas National Forest); Clay Davis (NEPA Planner, FRRD); Brett Sanders (Congressman LaMalfa’s Representative); Dennis Schmidt (Director of Public Works); Paula Daneluk (Director of Development Services) 2.02 Self-introduction of Forest Advisory Committee Members, Alternates, Guests, and Public – 5 Min. 3.00 Consent Agenda 3.01 Review and approve minutes of 7-27-20 – 5 Min. 4.00 Agenda 4.01 Paradise Recreation & Park District Magalia and Paradise Lake Loop Trails Project – Dan Efseaff, Director- 20 Min 4.02 Coordinating Committee Meeting results – Poe Relicensing Recreational Trail Letter from PG&E, Dave Steindorf of American Whitewater to share history and current situation:. -

Butte County Forest Advisory Committee

BUTTE COUNTY FOREST ADVISORY COMMITTEE August 23, 2021—5:00 P.M. Meeting via Zoom Join Zoom Meeting: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84353648421?pwd=bnprWUVJSTFpUVFkMEhNVzZmQ3pNUT09 One tap mobile +16699006833,,84353648421# US (San Jose) Dial by your location: +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) Meeting ID: 843 5364 8421 Passcode: 428997 ITEM NO. 1.00 Call to order – Zoom 2.00 Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America 2.01 Roll Call – Members: Nick Repanich, Thad Walker, Teri Faulkner, Trish Puterbaugh, Dan Taverner, Peggy Moak Alternates: Vance Severin, Bob Gage, Frank Stewart, Carolyn Denero, Holly Jorgensen Invited Guests: Deb Bumpus (Forest Supervisor, Lassen National Forest); Russell Nickerson,(District Ranger, Almanor Ranger District, Lassen National Forest); David Brillenz (District Ranger, Feather River Ranger District (FRRD), Plumas National Forest); Clay Davis (NEPA Planner, FRRD); Brett Sanders or Laura Page (Congressman LaMalfa’s Representative); Josh Pack (Director of Public Works); Paula Daneluk (Director, Development Services); Dan Efseaff (District Manager, Paradise Recreation and Park District); Representative (Butte County Fire Safe Council); Paul Gosselin (Deputy Director for SGMA, CA Dept. of Water Resources) 2.02 Self-introduction of Forest Advisory Committee Members, Alternates, Guests, and Public – 5 Min. 3.00 Consent Agenda 3.01 Review and Approve Minutes of 7-26-21 – 5 Min. 4.00 Agenda 4.01 Expansion of Paradise Recreation and Park Trails System - Dan Efseaff, District Manager –– 30 Min. 4.02 Sustainable -

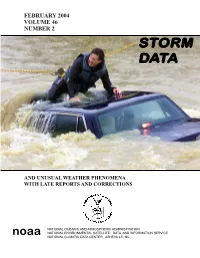

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....………..……

FEBRUARY 2004 VOLUME 46 NUMBER 2 SSTORMTORM DDATAATA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION noaa NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER, ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: A heavy rain event on February 5, 2004 led to fl ooding in Jackson, MS after 6 - 7 inches of rain fell in a six hour period. Lieutenant Tim Dukes of the Jackson (Hinds County, MS) Fire Department searches for possible trapped motorists inside a vehicle that was washed 200 feet down Town Creek in Jackson, Mississippi. Luckily, the vehicle was empty. (Photo courtesy: Chris Todd, The Clarion Ledger, Jackson, MS) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month …..…………….….........……..…………..…….…..…..... 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....………..……...........…............ 5 Additions/Corrections.......................................................................................................................... 109 Reference Notes.................................................................................................................................... 125 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: William Angel Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Herndon STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events re- sulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Climatic Data Center and the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confi rmed information on storms available to our staff at the time of publication. Late reports and corrections will be printed in each edition. -

FY2015 Outcome Evaluations of ANA Projects Report

FY 2015 Outcome Evaluations of Administration for Native Americans Projects Report to Congress FY 2015 Annual Report to Congress Outcome Evaluations of Administration for Native Americans Projects TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 2015 Key Findings ............................................................................................................................. 7 ANA SEDS Economic Development .............................................................................................. 11 ANA SEDS Social Development .................................................................................................... 12 ANA Environmental Regulatory Enhancement .............................................................................. 13 ANA Native Languages ................................................................................................................... 14 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................ 16 Aleut Community of St. Paul Island ................................................................................................. 17 Chugachmiut ..................................................................................................................................... 19 Cook Inlet Tribal Council, Inc. ........................................................................................................ -

Honey Lake Maidu Ethnogeography of Lassen County, California

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Honey Lake Maidu Ethnogeography of Lassen County, California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8xz6j609 Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 19(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Authors Simmons, William S Morales, Ron Williams, Viola et al. Publication Date 1997-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 2-31 (1997). Honey Lake Maidu Ethnogeography of Lassen County, California WILLIAM S. SIMMONS, Dept. of Anthropology, Univ. of California, Berkeley, CA 94720. RON MORALES, Descendant of Honey Lake Maidu and Chairman of Lassen Yah Monee Maidu Bear Dance Foundation, 1101 Arnold St., Susanville, CA 96130. VIOLA WILLIAMS, Descendant of Honey Lake Maidu, 340 Adella St., Susanville, CA 96130. STEVE CAMACHO, Teacher, Historian, Researcher, 471-000 Buckhom, Susanville, CA 96130. Based mainly upon the testimonies of nineteenth and twentieth century Maidu inhabitants of the Honey Lake Valley in Lassen County, California, we present a Maidu perspective on local knowledge, such as where they lived, hunted, gathered, and buried their dead in the prehistoric and early histori cal periods. Drawing on family tape recordings and interview notes in the possession of the authors, as well as a range of other sources, this article is intended as a contribution to Maidu ethnogeography in the Honey Lake Valley region. While acknowledging that several ethnic groups lived in or near this region in the early historical period, atui that boundaries are social construas that may overlap and about which groups may hold different interpretations, we document a cross-generational Maidu perspective on their territorial range in the remembered past. -

Sites Reservoir Project Public Draft EIR/EIS

18. Cultural/Tribal Cultural Resources 18.1 Introduction This chapter describes the cultural resources setting for the Extended, Secondary, and Primary study areas. Cultural resources are sites, buildings, structures, objects, and districts that may have traditional or cultural value. This broad range of resources includes archaeological sites that reflect the prehistoric and historic-era past; historic-era resources, such as buildings and structures; landscapes and districts; and traditional cultural properties (TCPs), i.e., those resources that are historically rooted in a community’s beliefs, customs, and practices.1 Tribal cultural resources (TCRs), which were established by the State of California under Assembly Bill (AB) 52 and are similar resources that have specific cultural value to Native Americans, are also addressed. Descriptions and maps of these three study areas are provided in Chapter 1 Introduction. Permits and authorizations for cultural and tribal resources are presented in Chapter 4 Environmental Compliance and Permit Summary. The regulatory setting for cultural resources is presented in Appendix 4A Environmental Compliance. This chapter focuses primarily on the Primary Study Area. Potential impacts in the Secondary and Extended study areas were evaluated and discussed qualitatively. Potential local and regional impacts from constructing, operating, and maintaining the alternatives were described and compared to applicable significance thresholds. Mitigation measures are provided for identified potentially significant impacts, where appropriate. 18.2 Affected Environment 18.2.1 Extended Study Area 18.2.1.1 Prehistoric Context Archaeologists study the physical evidence of past human behavior called “material culture.”2 The archaeologists look for changes in material culture over time and across geographic regions to reconstruct the past. -

The Historical Range of Beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a Review of the Evidence

Spring 2012 65 California Fish and Game 98(2):65-80; 2012 The historical range of beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a review of the evidence RICHARD B. LANMAN*, HEIDI PERRYMAN, BROCK DOLMAN, AND CHARLES D. JAMES Institute for Historical Ecology, 556 Van Buren Street, Los Altos, CA 94022, USA (RBL) Worth a Dam, 3704 Mt. Diablo Road, Lafayette, CA 94549, USA (HP) OAEC WATER Institute, 15290 Coleman Valley Road, Occidental, CA 95465, USA (BD) Bureau of Indian Affairs, Northwest Region, Branch of Environmental and Cultural Resources Management, Portland, OR 97232, USA (CDJ) *Correspondent: [email protected] The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) has not been considered native to the mid- or high-elevations of the western Sierra Nevada or along its eastern slope, although this mountain range is adjacent to the mammal’s historical range in the Pit, Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and their tributaries. Current California and Nevada beaver management policies appear to rest on assertions that date from the first half of the twentieth century. This review challenges those long-held assumptions. Novel physical evidence of ancient beaver dams in the north central Sierra (James and Lanman 2012) is here supported by a contemporary and expanded re-evaluation of historical records of occurrence by additional reliable observers, as well as new sources of indirect evidence including newspaper accounts, geographical place names, Native American ethnographic information, and assessments of habitat suitability. Understanding that beaver are native to the Sierra Nevada is important to contemporary management of rapidly expanding beaver populations. These populations were established by translocation, and have been shown to have beneficial effects on fish abundance and diversity in the Sierra Nevada, to stabilize stream incision in montane meadows, and to reduce discharge of nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment loads into fragile water bodies such as Lake Tahoe. -

USGS Topographic Maps of California

USGS Topographic Maps of California: 7.5' (1:24,000) Planimetric Planimetric Map Name Reference Regular Replace Ref Replace Reg County Orthophotoquad DRG Digital Stock No Paper Overlay Aberdeen 1985, 1994 1985 (3), 1994 (3) Fresno, Inyo 1994 TCA3252 Academy 1947, 1964 (pp), 1964, 1947, 1964 (3) 1964 1964 c.1, 2, 3 Fresno 1964 TCA0002 1978 Ackerson Mountain 1990, 1992 1992 (2) Mariposa, Tuolumne 1992 TCA3473 Acolita 1953, 1992, 1998 1953 (3), 1992 (2) Imperial 1992 TCA0004 Acorn Hollow 1985 Tehama 1985 TCA3327 Acton 1959, 1974 (pp), 1974 1959 (3), 1974 (2), 1994 1974 1994 c.2 Los Angeles 1994 TCA0006 (2), 1994, 1995 (2) Adelaida 1948 (pp), 1948, 1978 1948 (3), 1978 1948, 1978 1948 (pp) c.1 San Luis Obispo 1978 TCA0009 (pp), 1978 Adelanto 1956, 1968 (pp), 1968, 1956 (3), 1968 (3), 1980 1968, 1980 San Bernardino 1993 TCA0010 1980 (pp), 1980 (2), (2) 1993 Adin 1990 Lassen, Modoc 1990 TCA3474 Adin Pass 1990, 1993 1993 (2) Modoc 1993 TCA3475 Adobe Mountain 1955, 1968 (pp), 1968 1955 (3), 1968 (2), 1992 1968 Los Angeles, San 1968 TCA0012 Bernardino Aetna Springs 1958 (pp), 1958, 1981 1958 (3), 1981 (2) 1958, 1981 1981 (pp) c.1 Lake, Napa 1992 TCA0013 (pp), 1981, 1992, 1998 Agua Caliente Springs 1959 (pp), 1959, 1997 1959 (2) 1959 San Diego 1959 TCA0014 Agua Dulce 1960 (pp), 1960, 1974, 1960 (3), 1974 (3), 1994 1960 Los Angeles 1994 TCA0015 1988, 1994, 1995 (3) Aguanga 1954, 1971 (pp), 1971, 1954 (2), 1971 (3), 1982 1971 1954 c.2 Riverside, San Diego 1988 TCA0016 1982, 1988, 1997 (3), 1988 Ah Pah Ridge 1983, 1997 1983 Del Norte, Humboldt 1983 -

ED436973.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 436 973 FL 026 097 AUTHOR Martin, Joyce, Comp. TITLE Native American Languages: Subject Guide. INSTITUTION Arizona State Univ., Tempe. Univ. Library. PUB DATE 1999-08-00 NOTE 12p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: <http://www.asu.edu/lib/archives/labriola.htm> and <http://www.asu.edu/lib/archives/labriola.htm>. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Languages; Biblical Literature; Bilingual Education; Dictionaries; English (Second Language); Indigenous Populations; *Library Guides; Sign Language; Tape Recordings; Uncommonly Taught Languages IDENTIFIERS *Native Americans ABSTRACT This document is an eleven-page supplemental subject guide listing reference material that focuses on Native American languages that is not available in the Labriola National American Indian Data Center in the Arizona State University, Tempe (ASU) libraries. The guide is not comprehensive but offers a selective list of resources useful for developing language and vocabulary skills or researching a variety of topics dealing with native North American languages. Additional material may be found using the ASU online catalogue and the Arizona Southwest index. Contents include: bibles and hymnals; bibliographies; bilingual education, curriculum, and workbooks; culture, history, and language; dictionaries and grammar books; English as a Second Language; guides and handbooks; language tapes; linguistics; online access; sign language.(KFT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Native American Languages Subject Guide The following bibliography lists reference material dealing with Native American languages which is available in the Labriola National American Indian Data Center in the University Libraries. It is not comprehensive, but rather a selective list of resources useful for developing language and vocabulary skills, and/or researching a variety of topics dealing with Native North American languages. -

Map of the Elders: Cultivating Indigenous North Central California

HIYA ‘AA MA PICHAS ‘OPE MA HAMMAKO HE MA PAP’OYYISKO (LET US UNDERSTAND AGAIN OUR GRANDMOTHERS AND OUR GRANDFATHERS): MAP OF THE ELDERS: CULTIVATING INDIGENOUS NORTH CENTRAL CALIFORNIA CONSCIOUSNESS A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Diveena S. Marcus 2016 Indigenous Studies Ph.D. Graduate Program September 2016 ABSTRACT Hiya ʼAa Ma Pichas ʼOpe Ma Hammako He Ma Papʼoyyisko (Let Us Understand Again Our Grandmothers and Our Grandfathers): Map of the Elders, Cultivating Indigenous North Central California Consciousness By Diveena S. Marcus The Tamalko (Coast Miwok) North Central California Indigenous people have lived in their homelands since their beginnings. California Indigenous people have suffered violent and uncompromising colonial assaults since European contact began in the 16th century. However, many contemporary Indigenous Californians are thriving today as they reclaim their Native American sovereign rights, cultural renewal, and well- being. Culture Bearers are working diligently as advocates and teachers to re-cultivate Indigenous consciousness and knowledge systems. The Tamalko author offers Indigenous perspectives for hinak towis hennak (to make a good a life) through an ethno- autobiographical account based on narratives by Culture Bearers from four Indigenous North Central California Penutian-speaking communities and the author’s personal experiences. A Tamalko view of finding and speaking truth hinti wuskin ʼona (what the heart says) has been the foundational principle of the research method used to illuminate and illustrate Indigenous North Central California consciousness. -

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....………..…………..…..……………..……………..…

JANUARY 2001 VOLUME 43 NUMBER 01 STSTORMORM DDAATTAA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER noaa ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: Icicles hang from an orange tree with sprinklers running in an adjacent strawberry field in the background at sunrise on January 1, 2001. The photo was taken at Mike Lott’s Strawberry Farm in rural Eastern Hillsborough County of West- Central, FL. Low temperatures in the area were in the middle 20’s for six to nine hours. (Photograph courtesy of St. Petersburg Times Newspaper Photographer, Fraser Hale) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month ..……..…………………..……………..……………..……………..…. 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....………..…………..…..……………..……………..…. 5 Additions/Corrections ..………….……………………………………………………………………….. 92 Reference Notes ..……..………..……………..……………..……………..…………..………………… 122 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: Stephen Del Greco Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Mooring STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events resulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Climatic Data Center and the National Weather Service's (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confirmed information on storms available to our staff at the time of publication. Late reports and corrections will be printed in each edition. Except for limited editing to correct grammatical errors, the data in Storm Data are published as received.