Seriating Arrow Points from Dart Points Subdivide the Study Area Into Seven Sub-Regions Depicted in Figure 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 24, 2020—5:00 P.M

BUTTE COUNTY FOREST ADVISORY COMMITTEE August 24, 2020—5:00 P.M. Meeting via ZOOM Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89991617032?pwd=SGYzS3JYcG9mNS93ZjhqRkxSR2o0Zz09 Meeting ID: 899 9161 7032 Passcode: 300907 One tap mobile +16699006833,,89991617032# US (San Jose) +12532158782,,89991617032# US (Tacoma) Dial by your location +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) Meeting ID: 899 9161 7032 ITEM NO. 1.00 Call to order – Butte County Public Works Facility, Via ZOOM 2.00 Pledge of allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America 2.01 Roll Call – Members: Nick Repanich, Thad Walker, Teri Faulkner, Dan Taverner, Peggy Moak (Puterbaugh absent) Alternates: Vance Severin, Carolyn Denero, Bob Gage, Holly Jorgensen (voting Alt), Frank Stewart Invited Guests: Dan Efseaff,(Director, Paradise Recreation and Park District); Dave Steindorf (American Whitewater); Jim Houtman (Butte County Fire Safe Council); Taylor Nilsson (Butte County Fire Safe Council), Deb Bumpus (Forest Supervisor, Lassen National Forest); Russell Nickerson,(District Ranger, Almanor Ranger District, Lassen National Forest); Chris Carlton (Supervisor, Plumas National Forest); David Brillenz (District Ranger, Feather River Ranger District (FRRD), Plumas National Forest); Clay Davis (NEPA Planner, FRRD); Brett Sanders (Congressman LaMalfa’s Representative); Dennis Schmidt (Director of Public Works); Paula Daneluk (Director of Development Services) 2.02 Self-introduction of Forest Advisory Committee Members, Alternates, Guests, and Public – 5 Min. 3.00 Consent Agenda 3.01 Review and approve minutes of 7-27-20 – 5 Min. 4.00 Agenda 4.01 Paradise Recreation & Park District Magalia and Paradise Lake Loop Trails Project – Dan Efseaff, Director- 20 Min 4.02 Coordinating Committee Meeting results – Poe Relicensing Recreational Trail Letter from PG&E, Dave Steindorf of American Whitewater to share history and current situation:. -

Butte County Forest Advisory Committee

BUTTE COUNTY FOREST ADVISORY COMMITTEE August 23, 2021—5:00 P.M. Meeting via Zoom Join Zoom Meeting: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84353648421?pwd=bnprWUVJSTFpUVFkMEhNVzZmQ3pNUT09 One tap mobile +16699006833,,84353648421# US (San Jose) Dial by your location: +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) Meeting ID: 843 5364 8421 Passcode: 428997 ITEM NO. 1.00 Call to order – Zoom 2.00 Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America 2.01 Roll Call – Members: Nick Repanich, Thad Walker, Teri Faulkner, Trish Puterbaugh, Dan Taverner, Peggy Moak Alternates: Vance Severin, Bob Gage, Frank Stewart, Carolyn Denero, Holly Jorgensen Invited Guests: Deb Bumpus (Forest Supervisor, Lassen National Forest); Russell Nickerson,(District Ranger, Almanor Ranger District, Lassen National Forest); David Brillenz (District Ranger, Feather River Ranger District (FRRD), Plumas National Forest); Clay Davis (NEPA Planner, FRRD); Brett Sanders or Laura Page (Congressman LaMalfa’s Representative); Josh Pack (Director of Public Works); Paula Daneluk (Director, Development Services); Dan Efseaff (District Manager, Paradise Recreation and Park District); Representative (Butte County Fire Safe Council); Paul Gosselin (Deputy Director for SGMA, CA Dept. of Water Resources) 2.02 Self-introduction of Forest Advisory Committee Members, Alternates, Guests, and Public – 5 Min. 3.00 Consent Agenda 3.01 Review and Approve Minutes of 7-26-21 – 5 Min. 4.00 Agenda 4.01 Expansion of Paradise Recreation and Park Trails System - Dan Efseaff, District Manager –– 30 Min. 4.02 Sustainable -

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....………..……

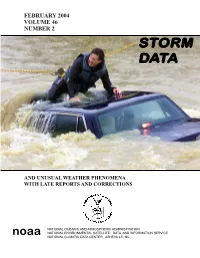

FEBRUARY 2004 VOLUME 46 NUMBER 2 SSTORMTORM DDATAATA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION noaa NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER, ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: A heavy rain event on February 5, 2004 led to fl ooding in Jackson, MS after 6 - 7 inches of rain fell in a six hour period. Lieutenant Tim Dukes of the Jackson (Hinds County, MS) Fire Department searches for possible trapped motorists inside a vehicle that was washed 200 feet down Town Creek in Jackson, Mississippi. Luckily, the vehicle was empty. (Photo courtesy: Chris Todd, The Clarion Ledger, Jackson, MS) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month …..…………….….........……..…………..…….…..…..... 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....………..……...........…............ 5 Additions/Corrections.......................................................................................................................... 109 Reference Notes.................................................................................................................................... 125 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: William Angel Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Herndon STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events re- sulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Climatic Data Center and the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confi rmed information on storms available to our staff at the time of publication. Late reports and corrections will be printed in each edition. -

The Historical Range of Beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a Review of the Evidence

Spring 2012 65 California Fish and Game 98(2):65-80; 2012 The historical range of beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a review of the evidence RICHARD B. LANMAN*, HEIDI PERRYMAN, BROCK DOLMAN, AND CHARLES D. JAMES Institute for Historical Ecology, 556 Van Buren Street, Los Altos, CA 94022, USA (RBL) Worth a Dam, 3704 Mt. Diablo Road, Lafayette, CA 94549, USA (HP) OAEC WATER Institute, 15290 Coleman Valley Road, Occidental, CA 95465, USA (BD) Bureau of Indian Affairs, Northwest Region, Branch of Environmental and Cultural Resources Management, Portland, OR 97232, USA (CDJ) *Correspondent: [email protected] The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) has not been considered native to the mid- or high-elevations of the western Sierra Nevada or along its eastern slope, although this mountain range is adjacent to the mammal’s historical range in the Pit, Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and their tributaries. Current California and Nevada beaver management policies appear to rest on assertions that date from the first half of the twentieth century. This review challenges those long-held assumptions. Novel physical evidence of ancient beaver dams in the north central Sierra (James and Lanman 2012) is here supported by a contemporary and expanded re-evaluation of historical records of occurrence by additional reliable observers, as well as new sources of indirect evidence including newspaper accounts, geographical place names, Native American ethnographic information, and assessments of habitat suitability. Understanding that beaver are native to the Sierra Nevada is important to contemporary management of rapidly expanding beaver populations. These populations were established by translocation, and have been shown to have beneficial effects on fish abundance and diversity in the Sierra Nevada, to stabilize stream incision in montane meadows, and to reduce discharge of nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment loads into fragile water bodies such as Lake Tahoe. -

USGS Topographic Maps of California

USGS Topographic Maps of California: 7.5' (1:24,000) Planimetric Planimetric Map Name Reference Regular Replace Ref Replace Reg County Orthophotoquad DRG Digital Stock No Paper Overlay Aberdeen 1985, 1994 1985 (3), 1994 (3) Fresno, Inyo 1994 TCA3252 Academy 1947, 1964 (pp), 1964, 1947, 1964 (3) 1964 1964 c.1, 2, 3 Fresno 1964 TCA0002 1978 Ackerson Mountain 1990, 1992 1992 (2) Mariposa, Tuolumne 1992 TCA3473 Acolita 1953, 1992, 1998 1953 (3), 1992 (2) Imperial 1992 TCA0004 Acorn Hollow 1985 Tehama 1985 TCA3327 Acton 1959, 1974 (pp), 1974 1959 (3), 1974 (2), 1994 1974 1994 c.2 Los Angeles 1994 TCA0006 (2), 1994, 1995 (2) Adelaida 1948 (pp), 1948, 1978 1948 (3), 1978 1948, 1978 1948 (pp) c.1 San Luis Obispo 1978 TCA0009 (pp), 1978 Adelanto 1956, 1968 (pp), 1968, 1956 (3), 1968 (3), 1980 1968, 1980 San Bernardino 1993 TCA0010 1980 (pp), 1980 (2), (2) 1993 Adin 1990 Lassen, Modoc 1990 TCA3474 Adin Pass 1990, 1993 1993 (2) Modoc 1993 TCA3475 Adobe Mountain 1955, 1968 (pp), 1968 1955 (3), 1968 (2), 1992 1968 Los Angeles, San 1968 TCA0012 Bernardino Aetna Springs 1958 (pp), 1958, 1981 1958 (3), 1981 (2) 1958, 1981 1981 (pp) c.1 Lake, Napa 1992 TCA0013 (pp), 1981, 1992, 1998 Agua Caliente Springs 1959 (pp), 1959, 1997 1959 (2) 1959 San Diego 1959 TCA0014 Agua Dulce 1960 (pp), 1960, 1974, 1960 (3), 1974 (3), 1994 1960 Los Angeles 1994 TCA0015 1988, 1994, 1995 (3) Aguanga 1954, 1971 (pp), 1971, 1954 (2), 1971 (3), 1982 1971 1954 c.2 Riverside, San Diego 1988 TCA0016 1982, 1988, 1997 (3), 1988 Ah Pah Ridge 1983, 1997 1983 Del Norte, Humboldt 1983 -

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....………..…………..…..……………..……………..…

JANUARY 2001 VOLUME 43 NUMBER 01 STSTORMORM DDAATTAA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER noaa ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: Icicles hang from an orange tree with sprinklers running in an adjacent strawberry field in the background at sunrise on January 1, 2001. The photo was taken at Mike Lott’s Strawberry Farm in rural Eastern Hillsborough County of West- Central, FL. Low temperatures in the area were in the middle 20’s for six to nine hours. (Photograph courtesy of St. Petersburg Times Newspaper Photographer, Fraser Hale) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month ..……..…………………..……………..……………..……………..…. 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....………..…………..…..……………..……………..…. 5 Additions/Corrections ..………….……………………………………………………………………….. 92 Reference Notes ..……..………..……………..……………..……………..…………..………………… 122 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: Stephen Del Greco Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Mooring STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events resulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Climatic Data Center and the National Weather Service's (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confirmed information on storms available to our staff at the time of publication. Late reports and corrections will be printed in each edition. Except for limited editing to correct grammatical errors, the data in Storm Data are published as received. -

Forested Communities of the Upper Montane in the Central and Southern Sierra Nevada

United States Department Forested Communities of the Upper of Agriculture Forest Service Montane in the Central and Southern Pacific Southwest Sierra Nevada Research Station Donald A. Potter General Technical Report PSW-GTR-169 Publisher: Pacific Southwest Research Station Albany, California Forest Service Mailing address: U.S. Department of Agriculture PO Box 245, Berkeley CA 94701-0245 Abstract (510) 559-6300 Potter, Donald A. 1998. Forested communities of the upper montane in the central and southern http://www.psw.fs.fed.us Sierra Nevada. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-169. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 319 p. September 1998 Upper montane forests in the central and southern Sierra Nevada of California were classified into 26 plant associations by using information collected from 0.1-acre circular plots. Within this region, the forested environment including the physiographic setting, geology, soils, and vegetation is described in detail. A simulation model is presented for this portion of the Sierra Nevada that refines discussions of climate, and disturbance regimes are described to illustrate the interaction between these features of the environment and vegetation in the study area. In the classification, plant associations are differentiated by floristic composition, environmental setting, and measurements of productivity. Differences in elevation, aspect, topographic setting, and soil properties generally distinguish each plant association described. A detailed description is presented for each plant association, including a discussion of the distribution, environment, vegetation, soils, productivity, coarse woody debris, range, wildlife, and management recommendations. A complete species list and tables for cross referencing specific characteristics of each association are provided. -

Birds of Northern California

BIRDS OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA AN ANNOTATED FIELD LIST Reprinted with Supplement Guy McCaskie Paul De Benediclis Richard Erickson Joseph Morlan BIRDS OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA AN ANNOTATED FIELD LIST . Second Edition by Guy McCaskie Paul De Benedictis Richard Erickson Joseph Morlan *** Designed and Edited by Nick Story for Golden Gate Audubon Society Berkeley, California Reprinted with Supplement, April 1988 Birds of Northern California: ~ 1979 by Golden Gate Audubon Society, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Golden Gate Audubon Society, Inc. 1550 Shattuck Ave., Suite 204 Berkeley, California 94709 Supplement copyright ~19B8 by Golden Gate Audubon Society TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface to the Second Edition iv Acknowledgements iv Introduction Species Districts Habitats . 4 Graphs and Notes 6 Field Identification 7 Map of Distributional Districts 5 Key to Graphs ..• 7 Appendix 1: Recent Records 78 Appendix 2: Introduced Species 81 Appendix 3: Name Changes 81 Bibliography 82 Supplement 85 Index •.• 98 iii PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION It has been twelve years since publication of the first edition of this book, and demand has been building for a secortd p.rinting. Golden Gate Audubon Society, the publisher, decided that a revision was needed and agreed to underwrite the cost of preparing one. McCaskie and De Benedictis had moved out of Northern California, and McCaskie felt that people still active in the region should revise it. Accordingly, Erickson and Morlan reviewed the current status of all species in the first edition, added new species found since, and updated the notes and graphs to reflect current knowledge. Erickson revised loons through alcids, Morlan doves through sparrows. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Erosion, Vegetation and the Evolution of Hillslopes in Upland Landscapes David T. Milodowski B.A. M.Sci. (Hons) Ph.D. Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences University of Edinburgh - 2016 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2016 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ....................................................................................................................... ix Lay Summary .............................................................................................................. xi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................. -

Six Rivers Project Desc

Over Snow Vehicle Snow Program Challenge Cost Share Agreements Initial Study/ Negative Declaration September 2009 State of California, Department of Parks and Recreation, Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation (OHMVR) Division Over Snow Vehicle Snow Program Challenge Cost Share Agreements Initial Study/ Negative Declaration September 2009 Prepared for: State of California, Department of Parks and Recreation, Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation (OHMVR) Division 1725 23rd Street, Suite 200, Sacramento, CA 95816 Prepared by: TRA Environmental Sciences, Inc. 545 Middlefield Road, Suite 200 Menlo Park, CA 94025 (650) 327-0429 (650) 327-4024 fax www.traenviro.com NEGATIVE DECLARATION Project: Over-Snow Vehicle Snow Program Challenge Cost Share Agreements Lead Agency: California Department of Parks and Recreation Availability of Documents: The Initial Study for this Negative Declaration is available for review at the following locations: California Department of Parks and Recreation Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation Division 1725 23rd Street, Suite 200 Sacramento, CA 95816 Contact: Connie Latham Email: [email protected] Project Description: The proposed project is the issuance of Challenge Cost Share Agreements (CSA) funding the Snow Program occurring in National Forests throughout California. CSAs would be issued to eleven National Forests and three county agencies for snow plowing, trail grooming, restroom and warming hut cleaning services, and garbage collection at trailheads. FINDINGS The Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation (OHMVR) Division, having reviewed the Initial Study for the proposed project, finds that: 1. The proposed project will support the winter recreation program in National Forests by providing snow plowing, trail grooming, cleaning of restrooms and warming huts, and garbage collection. -

Sierra Nevada’S Endless Landforms Are Playgrounds for to Admire the Clear Fragile Shards

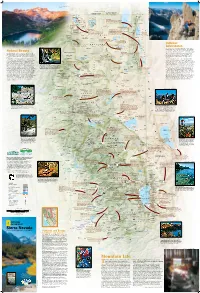

SIERRA BUTTES AND LOWER SARDINE LAKE RICH REID Longitude West 121° of Greenwich FREMONT-WINEMA OREGON NATIONAL FOREST S JOSH MILLER PHOTOGRAPHY E E Renner Lake 42° Hatfield 42° Kalina 139 Mt. Bidwell N K WWII VALOR Los 8290 ft IN THE PACIFIC ETulelake K t 2527 m Carr Butte 5482 ft . N.M. N. r B E E 1671 m F i Dalton C d Tuber k Goose Obsidian Mines w . w Cow Head o I CLIMBING THE NORTHEAST RIDGE OF BEAR CREEK SPIRE E Will Visit any of four obsidian mines—Pink Lady, Lassen e Tule Homestead E l Lake Stronghold l Creek Rainbow, Obsidian Needles, and Middle Fork Lake Lake TULE LAKE C ENewell Clear Lake Davis Creek—and take in the startling colors and r shapes of this dense, glass-like lava rock. With the . NATIONAL WILDLIFE ECopic Reservoir L proper permit you can even excavate some yourself. a A EM CLEAR LAKE s EFort Bidwell REFUGE E IG s Liskey R NATIONAL WILDLIFE e A n N Y T REFUGE C A E T r W MODOC R K . Y A B Kandra I Blue Mt. 5750 ft L B T Y S 1753 m Emigrant Trails Scenic Byway R NATIONAL o S T C l LAVA E Lava ows, canyons, farmland, and N E e Y Cornell U N s A vestiges of routes trod by early O FOREST BEDS I W C C C Y S B settlers and gold miners. 5582 ft r B K WILDERNESS Y . C C W 1701 m Surprise Valley Hot Springs I Double Head Mt. -

Fredonyer Butte Trail Project Eagle Lake Ranger District, Lassen National Forest Lassen County, California April 2020 Introducti

Fredonyer Butte Trail Project Eagle Lake Ranger District, Lassen National Forest Lassen County, California April 2020 Introduction The Eagle Lake Ranger District (ELRD), Lassen National Forest (LNF) proposes to develop approximately 24.5 miles of multi-use, non-motorized loop trails and two trailheads around Fredonyer Butte, approximately 10 miles west of Susanville, CA. The Proposed Action involves development of non-motorized trails to be used for hiker/pedestrian, bicycle, and horse trails, near Fredonyer Butte and includes construction of three separate but connected trails (Downhill Flow, Fredonyer Crest/Peak, Goumaz Campground) and a short spur trail (Little Fredonyer Butte Spur). The Downhill Flow Trail would be approximately 7.5 miles long and travel in a northeasterly direction generally following SR 36. The Fredonyer Crest/Peak Trail would also run in a northeasterly direction, would have a short bypass trail, and would be approximately 9.7 miles in length. Together, these two trails would provide a loop around Little Fredonyer and Fredonyer Butte. These trails would connect with the existing Bizz Johnson National Recreation Trail (NRT) and the Southside Trail at the Devil's Corral Trailhead. The Goumaz Campground Trail would travel north from SR 36 to the Bizz Johnson NRT at Goumaz Campground and would be approximately 5.4 miles in length. The trail would use approximately 1.2 miles of an existing road on its northern end and would use an existing bridge to cross Susan River. The Little Fredonyer Butte Spur would be approximately 0.5 mile and would travel north from the Fredonyer Peak/Crest Trail to the summit of Little Fredonyer.