The Historical Range of Beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a Review of the Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seriating Arrow Points from Dart Points Subdivide the Study Area Into Seven Sub-Regions Depicted in Figure 1

PREHISTORY CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 103 SSSPPPAAATIALTIALTIAL ANDANDAND TEMPORALEMPORALEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION OFOFOF ROSEOSEOSE SPRINGPRINGPRING PROJECTILEROJECTILEROJECTILE POINTSOINTSOINTS INININ THETHETHE NORTHORTHORTH-C-C-CENTRALENTRALENTRAL SIERRAIERRAIERRA NEVEVEVADAADAADA RICHARD W. DEIS Rose Spring corner-notched projectile points have been used within the North-Central Sierra Nevada region primarily to date surface assemblages, in an attempt to develop temporal affinities between sites and to trace technological innovation (i.e. introduction of the bow and arrow). Temporal placements have primarily been based upon projectile point cross-dating using typologies established for the Great Basin, without regard for a demonstrated link to this region of study. This paper presents the results of analysis that addressed the utility of Rose Spring corner-notched points as temporal markers, and presents implications for the results of this study. ose Spring corner-notched projectile points Rivers) which are located along the eastern margin of have been used within the North-Central the project area. RSierra Nevada region to date surface assemblages, in an attempt to develop temporal affinities between sites and to trace technological TYPE CONCEPT AND innovation, i.e. introduction of the bow and arrow. DEVELOPMENT OF TYPOLOGIES Temporal placements have primarily been based upon projectile point cross-dating using typologies Definitions of types used in this study are established for the Great Basin, without regard for a according to Steward (1954) who defined these in demonstrated link within the study region. terms of morphology, historical significance, functional traits or cultural characteristics. This paper briefly summarizes more extensive Morphological types are the most basic and consist of research presented in an MA thesis of the same title descriptions of form or visually observed (Deis 1999). -

Appendices – Part 2

TKPOA Corporation Yard Relocation Project Susan Lindström, Ph.D. May 2018 7 Consulting Archaeologist (2) A resource included in a local register of historical resources, as defined in section 5020.1(k) of the Public Resources Code or identified as significant in an historical resource survey meeting the requirements section 5024.1(g) of the Public Resources Code, shall be presumed to be historically or culturally significant. Public agencies must treat any such resource as significant unless the preponderance of evidence demonstrates that it is not historically or culturally significant. (3) Any object, building, structure, site, area, place, record, or manuscript which a lead agency determines to be historically significant or significant in the architectural, engineering, scientific, economic, agricultural, educational, social, political, military, or cultural annals of California may be considered to be an historical resource, provided the lead agency’s determination is supported by substantial evidence in light of the whole record. The Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) has also adopted procedures (stated in Chapter 67 of the TRPA Code of Ordinances) for the identification, recognition, protection, and preservation of the region’s significant cultural, historical, archaeological, and paleontological resources. Sections 67.3.2, 67.4 and 67.5 require a site survey by a qualified archaeologist, an inventory of any extant cultural resources, and consultation with the appropriate Native American group. Provisions for a report documenting compliance with the TRPA Code are contained in Section 67.7. Within this regulatory context, cultural resource studies are customarily performed in a series of phases, each one building upon information gained from the prior study. -

Volcanic Legacy

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacifi c Southwest Region VOLCANIC LEGACY March 2012 SCENIC BYWAY ALL AMERICAN ROAD Interpretive Plan For portions through Lassen National Forest, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Tule Lake, Lava Beds National Monument and World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................4 Background Information ........................................................................................................................4 Management Opportunities ....................................................................................................................5 Planning Assumptions .............................................................................................................................6 BYWAY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................................7 Management Goals ..................................................................................................................................7 Management Objectives ..........................................................................................................................7 Visitor Experience Goals ........................................................................................................................7 Visitor -

August 24, 2020—5:00 P.M

BUTTE COUNTY FOREST ADVISORY COMMITTEE August 24, 2020—5:00 P.M. Meeting via ZOOM Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89991617032?pwd=SGYzS3JYcG9mNS93ZjhqRkxSR2o0Zz09 Meeting ID: 899 9161 7032 Passcode: 300907 One tap mobile +16699006833,,89991617032# US (San Jose) +12532158782,,89991617032# US (Tacoma) Dial by your location +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) Meeting ID: 899 9161 7032 ITEM NO. 1.00 Call to order – Butte County Public Works Facility, Via ZOOM 2.00 Pledge of allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America 2.01 Roll Call – Members: Nick Repanich, Thad Walker, Teri Faulkner, Dan Taverner, Peggy Moak (Puterbaugh absent) Alternates: Vance Severin, Carolyn Denero, Bob Gage, Holly Jorgensen (voting Alt), Frank Stewart Invited Guests: Dan Efseaff,(Director, Paradise Recreation and Park District); Dave Steindorf (American Whitewater); Jim Houtman (Butte County Fire Safe Council); Taylor Nilsson (Butte County Fire Safe Council), Deb Bumpus (Forest Supervisor, Lassen National Forest); Russell Nickerson,(District Ranger, Almanor Ranger District, Lassen National Forest); Chris Carlton (Supervisor, Plumas National Forest); David Brillenz (District Ranger, Feather River Ranger District (FRRD), Plumas National Forest); Clay Davis (NEPA Planner, FRRD); Brett Sanders (Congressman LaMalfa’s Representative); Dennis Schmidt (Director of Public Works); Paula Daneluk (Director of Development Services) 2.02 Self-introduction of Forest Advisory Committee Members, Alternates, Guests, and Public – 5 Min. 3.00 Consent Agenda 3.01 Review and approve minutes of 7-27-20 – 5 Min. 4.00 Agenda 4.01 Paradise Recreation & Park District Magalia and Paradise Lake Loop Trails Project – Dan Efseaff, Director- 20 Min 4.02 Coordinating Committee Meeting results – Poe Relicensing Recreational Trail Letter from PG&E, Dave Steindorf of American Whitewater to share history and current situation:. -

Butte County Forest Advisory Committee

BUTTE COUNTY FOREST ADVISORY COMMITTEE August 23, 2021—5:00 P.M. Meeting via Zoom Join Zoom Meeting: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84353648421?pwd=bnprWUVJSTFpUVFkMEhNVzZmQ3pNUT09 One tap mobile +16699006833,,84353648421# US (San Jose) Dial by your location: +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) Meeting ID: 843 5364 8421 Passcode: 428997 ITEM NO. 1.00 Call to order – Zoom 2.00 Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America 2.01 Roll Call – Members: Nick Repanich, Thad Walker, Teri Faulkner, Trish Puterbaugh, Dan Taverner, Peggy Moak Alternates: Vance Severin, Bob Gage, Frank Stewart, Carolyn Denero, Holly Jorgensen Invited Guests: Deb Bumpus (Forest Supervisor, Lassen National Forest); Russell Nickerson,(District Ranger, Almanor Ranger District, Lassen National Forest); David Brillenz (District Ranger, Feather River Ranger District (FRRD), Plumas National Forest); Clay Davis (NEPA Planner, FRRD); Brett Sanders or Laura Page (Congressman LaMalfa’s Representative); Josh Pack (Director of Public Works); Paula Daneluk (Director, Development Services); Dan Efseaff (District Manager, Paradise Recreation and Park District); Representative (Butte County Fire Safe Council); Paul Gosselin (Deputy Director for SGMA, CA Dept. of Water Resources) 2.02 Self-introduction of Forest Advisory Committee Members, Alternates, Guests, and Public – 5 Min. 3.00 Consent Agenda 3.01 Review and Approve Minutes of 7-26-21 – 5 Min. 4.00 Agenda 4.01 Expansion of Paradise Recreation and Park Trails System - Dan Efseaff, District Manager –– 30 Min. 4.02 Sustainable -

Central California Native Americans

Central California Native Americans By: Janessa Boom, Matthew Navarrette, Angel Villa, Michael Ruiz, Alejandro Montiel, Jessica Jauregui, Nicholas Hardyman Settlement Patterns Central California was a densely populated cultural area with vast amounts of natural resources at hand. Taking advantage of central California’s various ecotones, the people exploited a plethora of resources using their ingenious technological and cultural expertise. As a general rule of thumb, the various tribes of central California organized themselves according to the availability of resources, i.e., if resources were found to be more densely packed within a given tribal area, one could expect to find a direct correlation in the tribe’s settlement pattern. A. Washoe Tribe- Located in the eastern part of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the Washoe Tribal settlements could typically be found 4-5,000 ft above the resource-rich Carson and Truckee river systems. Utilizing their short distance from the water, the Washoe tribe always had an abundant amount of food due to hunting both the fish swimming in the river, and the large game that came to the water to drink. B. Nisenan Tribe- Much like their Washoe neighbors in the east, the Nisenan Tribe prefered to live above rivers that stemmed from the Sierra Nevada Mountain range (Yuba, Bear, and American Rivers). Despite their similarities to the Washoe, the Nisenan also inhabited the valleys just north of Sacramento. While communities living above rivers tended to small, those located in the central valley could have as many as 500 inhabitants. C. Yana Tribe- While both the Nisenan and Washoe tribes utilized river systems within their tribal areas, the Yana lacked such large rivers. -

1 LAHONTAN MOUNTAIN SUCKER Catostomus Lahontan (Rutter

LAHONTAN MOUNTAIN SUCKER Catostomus lahontan (Rutter) Status: Moderate Concern. The Lahontan mountain sucker does not appear to be at risk of extinction in California in the near future; however, many populations are declining and their range is fragmented. Description: Mountain suckers are small (adults 12-20 cm TL), with subterminal mouths and full lips that are covered by many large papillae (Moyle 2002). Their lips are protrusible, have deep grooves where the upper and lower lips meet, and a cleft on the middle of the lower lip. The lower lip has two semicircular smooth areas along the inner margin next to a conspicuous cartilaginous plate that is used for scraping. The front of the upper lip is smooth. They have 75-92 scales along the lateral line and 23-37 gill rakers on the first gill arch. Fin rays typically number 10 (range 8-13) and nine for the dorsal and pelvic fins, respectively. An axillary process is easily visible at the base of the pelvic fins. Internally, their intestine is long (up to six times TL), and the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritoneum) is black. Their coloration is brown to olive green on the dorsal and lateral surfaces, white to yellow on their bellies, and dark brown in blotches in a lateral row or line. Mature males have two lateral bands, one red-orange on top of another that is black-green. Spawning males have tubercles covering their bodies and fins, with the exception of the dorsal fin. Tubercles on the enlarged anal fin become especially prominent. Spawning females also have tubercles but only on the top and sides of their heads and bodies. -

The Nevada Inter-Tribal Indian Conference (University of Nevada, May 1-2, 1964)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 050 872 RC 005 304 TITLE Proceedings: The Nevada Inter-tribal Indian Conference (University of Nevada, May 1-2, 1964). INSTITUTION Nevada Univ., Reno. Center for Western North American Studies. PUB DATE 10 Apr 65 NOTE 100p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture, *American Indians, Attitudes, *Education, History, Intercommunication, *Legal Problems, *Political Issues, *Social Attitudes IDENTIFIERS *Nevada ABSTRACT The conference report of the 1964 Nevada Inter-tribal Indian Conference, designed to encourage cooperation and communication between Indians and non-Indians, deals with(a) Indians and opportunity,(b) Indians and the community, and(c) Indians and legislation. The document also records narration reflecting the attitudes of Indians in Nevada toward their life situation. Additionally, emphasis is given to the claims cases of such tribes as the Washoe, the Western Shoshone, and the Northern Paiute. This material "should prove valuable to those who are interested in Indian affairs, Nevada history and anthropology, social work and Indian education." (MB) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION S. WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION VHS DOCUMENT HAS SEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRO M THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATEO DO NOT NECES SARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU CATION POSITION OR POLICY. A THE NEVADA INTERTRIBAL INDIAN CONFERENCE PRESENTED MAY 1 and 2, 1964, by THE UNIVERSITY ONEVADA Statewide Services and THE INTERTRIBAL COUNCIL OF NEVADA PROCEEDINGS Edited and Published by the CENTER FOR WESTERN NORTH AMERICAN STUDIES DESERT RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO, NEVADA 89507 CENTER FOR WESTERN NORTH AMERICAN STUDIES, April 10, 1965 DESERT RESEARCH INSTITUTE The Center for Western North American Studies is very pleased to make the proceedings of this significant Conference available to the public and to the participants. -

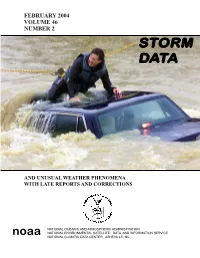

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....………..……

FEBRUARY 2004 VOLUME 46 NUMBER 2 SSTORMTORM DDATAATA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION noaa NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER, ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: A heavy rain event on February 5, 2004 led to fl ooding in Jackson, MS after 6 - 7 inches of rain fell in a six hour period. Lieutenant Tim Dukes of the Jackson (Hinds County, MS) Fire Department searches for possible trapped motorists inside a vehicle that was washed 200 feet down Town Creek in Jackson, Mississippi. Luckily, the vehicle was empty. (Photo courtesy: Chris Todd, The Clarion Ledger, Jackson, MS) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month …..…………….….........……..…………..…….…..…..... 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....………..……...........…............ 5 Additions/Corrections.......................................................................................................................... 109 Reference Notes.................................................................................................................................... 125 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: William Angel Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Herndon STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events re- sulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Climatic Data Center and the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confi rmed information on storms available to our staff at the time of publication. Late reports and corrections will be printed in each edition. -

Annual Senior Fun Day Bonds Elders, Community

VOLUME XII ISSUE 7 August 31, 2017 Annual Senior Fun Day Bonds Elders, Community Colony event renews friendships, celebrates gift of experience, wisdom with age In Native American tribal Plus, it was the principle pants showed off their person- communities, elders are the of Reno-Sparks Indian Colony alities by wearing unique hats wisdom-keepers as they know (RSIC) Chairman Arlan D. that culminated with a hat our history, know our culture Melendez’s welcoming contest via loudest applause. and educate the next genera- remarks. Many of the elders played tion. “It doesn’t matter where chair volleyball. Everyone For the Paiute, Shoshone and you’re from, we are all Native, enjoyed the catered lunch Washoe people, elders are held and we are all family,” compliments of Bertha in the highest regard. Chairman Melendez said. Miranda's Mexican Food Nowhere was that more “Today’s event shows that right Restaurant and Cantina. There evident than at the recent Reno- here.” also was bingo with prizes as Sparks Indian Colony Senior Besides meeting and greeting well as many information Fun Day. friends from afar, the partici- Continued on page 5 Organized and managed by the RSIC Senior Program, the annual event drew over 350 participants from as far away as Bishop, Calif., and Fort McDermitt, which straddles the Oregon—Nevada border. Teresa Bill, one of the RSIC staff members who helps orchestrate the event, said that the mission for Senior Fun Day is simple. “We have elders from so many different reservations this gives them an chance to see family and friends and catch up,” Bill said. -

University of California

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Resiliency of Native American Women Basket Weavers from California, Great Basin, and the Southwest Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/422088q0 Author Roberts, Meranda Diane Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Resiliency of Native American Women Basket Weavers from California, Great Basin, and the Southwest A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Meranda Diane Roberts September 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Clifford E. Trafzer, Chairperson Dr. Rebecca ‘Monte’ Kugel Dr. Anthony Macias Copyright by Meranda Diane Roberts 2018 The Dissertation of Meranda Diane Roberts is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Resiliency of Native American Women Basket Weavers of California, Great Basin, and the Southwest by Meranda Diane Roberts Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in History University of California, Riverside, September 2018 Dr. Clifford E. Trafzer, Chairperson Native American women from the American Southwest have always used basket weaving to maintain relationships with nature, their spirituality, tribal histories, sovereignty, and their ancestors. However, since the late nineteenth century, with the emergence of a tremendous tourist industry in the American West, non-Indians have perceived -

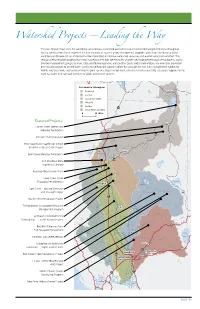

Watershed Projects—Leading The

Watershed Projects—Leading the Way The past 10 years have seen the completion of numerous watershed assessments and watershed management plans throughout the Sacramento River Basin. However, the true measure of success of any management program comes from the ability to affect conditions on the ground, i.e., implement actions to protect or improve watershed resources and overall watershed condition. This section briefly describes projects from each subregion area that are examples of watershed improvement work being done by locally directed management groups; by local, state, and federal agencies; and by other public and private entities. The examples presented here include projects to benefit water quality, streamflow and aquatic habitat, fish passage, fire and fuels management, habitat for wildlife and waterfowl, eradication of invasive plant species, flood management, and watershed stewardship education. Support for this work has come from a broad spectrum of public and private sources. Sacramento Subregions Northeast Lakeview Eastside OREGON Sacramento Valley CALIFORNIA Westside 5 Goose Feather 97 Lake Yuba, American & Bear 0 20 Miles Featured Projects: Alturas Lassen Creek Stream and Mt Shasta r Meadow Restoration e v i R 299 395 t i Pit River Channel Erosion P r e er iv iv R R o t RCD Cooperative Sagebrush Steppe n e m a r d c u Iniatitive — Butte Creek Project a o r S l 101 C e v c i R Lake M Burney Shasta Bear Creek Meadow Restoration Pit 299 CA NEVA Iron Mountain Mine LIFORNIA Eagle Superfund Cleanup Lake Redding DA Redding Allied Stream Team d Cr. Cottonwoo Lower Clear Creek Floodway Rehabilitation Honey Lake Red Bluff Lake Almanor Cow Creek— Bassett Diversion Fish Passage Project 395 r.