1 LAHONTAN MOUNTAIN SUCKER Catostomus Lahontan (Rutter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martis Valley Groundwater Basin Sustainable Groundwater Management Act Alternative Submittal

MARTIS VALLEY GROUNDWATER BASIN SUSTAINABLE GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT ACT ALTERNATIVE SUBMITTAL December 22, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS MARTIS VALLEY GROUNDWATER BASIN SGMA ALTERNATIVE SUBMITTAL ........................ 1 PART ONE: DESCRIPTION OF HYDROGEOLOGY OF MVGB ........................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION/OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................... 4 2. BASIN HYDROGEOLOGY ............................................................................................................ 4 2.1. Soils and Geology ......................................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Groundwater Recharge and Discharge ......................................................................................... 9 2.3. Groundwater in Storage .............................................................................................................. 14 3. DESCRIPTION OF BENEFICIAL USES...................................................................................... 14 PART TWO: BASIN MANAGEMENT ORGANIZATION AND PLAN ................................................ 15 1. GENERAL INFORMATION ......................................................................................................... 15 1.1. Summary of Management Approach, Organization of Partners, and General Conditions in the MVGB ................................................................................................................................................... -

Bear Creek Watershed Assessment Report

BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT PLACER COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Prepared by: PO Box 8568 Truckee, California 96162 February 16, 2018 And Dr. Susan Lindstrom, PhD BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA February 16, 2018 A REPORT PREPARED FOR: Truckee River Watershed Council PO Box 8568 Truckee, California 96161 (530) 550-8760 www.truckeeriverwc.org by Brian Hastings Balance Hydrologics Geomorphologist Matt Wacker HT Harvey and Associates Restoration Ecologist Reviewed by: David Shaw Balance Hydrologics Principal Hydrologist © 2018 Balance Hydrologics, Inc. Project Assignment: 217121 800 Bancroft Way, Suite 101 ~ Berkeley, California 94710-2251 ~ (510) 704-1000 ~ [email protected] Balance Hydrologics, Inc. i BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA < This page intentionally left blank > ii Balance Hydrologics, Inc. BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Project Goals and Objectives 1 1.2 Structure of This Report 4 1.3 Acknowledgments 4 1.4 Work Conducted 5 2 BACKGROUND 6 2.1 Truckee River Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) 6 2.2 Water Resource Regulations Specific to Bear Creek 7 3 WATERSHED SETTING 9 3.1 Watershed Geology 13 3.1.1 Bedrock Geology and Structure 17 3.1.2 Glaciation 18 3.2 Hydrologic Soil Groups 19 3.3 Hydrology and Climate 24 3.3.1 Hydrology 24 3.3.2 Climate 24 3.3.3 Climate Variability: Wet and Dry Periods 24 3.3.4 Climate Change 33 3.4 Bear Creek Water Quality 33 3.4.1 Review of Available Water Quality Data 33 3.5 Sediment Transport 39 3.6 Biological Resources 40 3.6.1 Land Cover and Vegetation Communities 40 3.6.2 Invasive Species 53 3.6.3 Wildfire 53 3.6.4 General Wildlife 57 3.6.5 Special-Status Species 59 3.7 Disturbance History 74 3.7.1 Livestock Grazing 74 3.7.2 Logging 74 3.7.3 Roads and Ski Area Development 76 4 WATERSHED CONDITION 81 4.1 Stream, Riparian, and Meadow Corridor Assessment 81 Balance Hydrologics, Inc. -

Martis Valley Groundwater Management Plan

Martis Valley Groundwater Management Plan April, 2013 Free space Prepared for Northstar Community Services District Placer County Water Agency Truckee Donner Public Utility District Client Logo (optional) Northstar Community Services District Free space Martis Valley Groundwater Management Plan Prepared for Truckee Donner Public Utility District, Truckee, California Placer County Water Agency, Auburn, California Northstar Community Services District, Northstar, California April 18, 2013 140691 MARTIS VALLEY GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN NEVADA AND PLACER COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA SIGNATURE PAGE Signatures of principal personnel responsible for the development of the Martis Valley Groundwater Management Plan are exhibited below: ______________________________ Tina M. Bauer, P.G. #6893, CHG #962 Brown and Caldwell, Project Manager ______________________________ David Shaw, P.G. #8210 Balance Hydrologics, Inc., Project Geologist ______________________________ John Ayres, CHG #910 Brown and Caldwell, Hydrogeologist 10540 White Rock Road, Suite 180 Rancho Cordova, California 95670 This Groundwater Management Plan (GMP) was prepared by Brown and Caldwell under contract to the Placer County Water Agency, Truckee Donner Public Utility District and Northstar Community Services District. The key staff involved in the preparation of the GMP are listed below. Brown and Caldwell Tina M. Bauer, PG, CHg, Project Manager John Ayres, PG,CHg, Hydrogeologist and Public Outreach Brent Cain, Hydrogeologist and Principal Groundwater Modeler Paul Selsky, PE, Quality -

Martis Wildlife Area Restoration Project

Basis of Design – Martis Wildlife Area Restoration Project February 2018 Prepared for: Sierra Ecosystems Associates 2311 Lake Tahoe Boulevard, Suite 8 South Lake Tahoe, CA 96150 Truckee River Watershed Council P.O. Box 8568 1900 N. Northlake Way, Suite 211 Truckee, CA 96162 Seattle, WA 98103 SIERRA ECOSYSTEM ASSOCIATES/TRUCKEE RIVER WATERSHED COUNCIL . MARTIS WILDLIFE AREA RESTORATION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Project Background ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Geomorphic Condition ...................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Basin Characteristics & Hydrology ................................................................................................................... 3 4. Restoration Goals and Design .......................................................................................................................... 6 5. Hydraulic Analysis ............................................................................................................................................ 13 6. References ....................................................................................................................................................... 17 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Martis Wildlife Area Restoration Project Area ...................................................................................... 1 Figure 2. Regional -

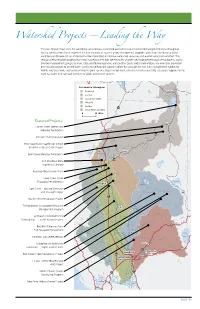

Watershed Projects—Leading The

Watershed Projects—Leading the Way The past 10 years have seen the completion of numerous watershed assessments and watershed management plans throughout the Sacramento River Basin. However, the true measure of success of any management program comes from the ability to affect conditions on the ground, i.e., implement actions to protect or improve watershed resources and overall watershed condition. This section briefly describes projects from each subregion area that are examples of watershed improvement work being done by locally directed management groups; by local, state, and federal agencies; and by other public and private entities. The examples presented here include projects to benefit water quality, streamflow and aquatic habitat, fish passage, fire and fuels management, habitat for wildlife and waterfowl, eradication of invasive plant species, flood management, and watershed stewardship education. Support for this work has come from a broad spectrum of public and private sources. Sacramento Subregions Northeast Lakeview Eastside OREGON Sacramento Valley CALIFORNIA Westside 5 Goose Feather 97 Lake Yuba, American & Bear 0 20 Miles Featured Projects: Alturas Lassen Creek Stream and Mt Shasta r Meadow Restoration e v i R 299 395 t i Pit River Channel Erosion P r e er iv iv R R o t RCD Cooperative Sagebrush Steppe n e m a r d c u Iniatitive — Butte Creek Project a o r S l 101 C e v c i R Lake M Burney Shasta Bear Creek Meadow Restoration Pit 299 CA NEVA Iron Mountain Mine LIFORNIA Eagle Superfund Cleanup Lake Redding DA Redding Allied Stream Team d Cr. Cottonwoo Lower Clear Creek Floodway Rehabilitation Honey Lake Red Bluff Lake Almanor Cow Creek— Bassett Diversion Fish Passage Project 395 r. -

The Last Decade of Research in the Tahoe-Truckee Area And

TAHOE REACH REVISITED: THE LATEST PLEISTOCENE/EARLY HOLOCENE IN THE TAHOE SIERRA SHARON A. WAECHTER FAR WESTERN ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH GROUP DAVIS, CALIFORNIA WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY WILLIAM W. BLOOMER LITHIC ARTS MARKLEEVILLE, CALIFORNIA The last decade of research in the Tahoe-Truckee area and surrounding High Sierra has provided clear evidence of early Holocene and perhaps latest Pleistocene human activity, probably coming immediately on the heels of the Tioga glacial retreat. In this discussion we summarize this research, and compare environmental proxy data and obsidian hydration profiles from high-elevation sites in Sierra, Placer, Nevada, El Dorado, Alpine, and Washoe counties, to suggest “big-picture” trends in prehistoric use of the Tahoe Sierra. The title “Tahoe Reach Revisited” is in reference to work by Robert Elston, Jonathon Davis, and various of their colleagues along the Tahoe Reach of the Truckee River – that section of the river from Lake Tahoe to Martis Creek (Figure 1). In the 1970s these researchers did the first substantive archaeology in the Truckee Basin, and developed a cultural chronology that has stood for 30 years without significant revision – not, as I’m sure Elston would agree, because it was completely accurate, but because no one offered any meaningful alternative. Instead, archaeologists working in the Tahoe Sierra and environs – even as far away as the western foothills – simply compared their data to the Tahoe Reach model to date their sites: “Lots of big basalt tools? It must be Martis.” But this is not a paper about Martis. My focus instead is on a much earlier period, which Elston and his colleagues called the Tahoe Reach Phase. -

The Historical Range of Beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a Review of the Evidence

Spring 2012 65 California Fish and Game 98(2):65-80; 2012 The historical range of beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a review of the evidence RICHARD B. LANMAN*, HEIDI PERRYMAN, BROCK DOLMAN, AND CHARLES D. JAMES Institute for Historical Ecology, 556 Van Buren Street, Los Altos, CA 94022, USA (RBL) Worth a Dam, 3704 Mt. Diablo Road, Lafayette, CA 94549, USA (HP) OAEC WATER Institute, 15290 Coleman Valley Road, Occidental, CA 95465, USA (BD) Bureau of Indian Affairs, Northwest Region, Branch of Environmental and Cultural Resources Management, Portland, OR 97232, USA (CDJ) *Correspondent: [email protected] The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) has not been considered native to the mid- or high-elevations of the western Sierra Nevada or along its eastern slope, although this mountain range is adjacent to the mammal’s historical range in the Pit, Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and their tributaries. Current California and Nevada beaver management policies appear to rest on assertions that date from the first half of the twentieth century. This review challenges those long-held assumptions. Novel physical evidence of ancient beaver dams in the north central Sierra (James and Lanman 2012) is here supported by a contemporary and expanded re-evaluation of historical records of occurrence by additional reliable observers, as well as new sources of indirect evidence including newspaper accounts, geographical place names, Native American ethnographic information, and assessments of habitat suitability. Understanding that beaver are native to the Sierra Nevada is important to contemporary management of rapidly expanding beaver populations. These populations were established by translocation, and have been shown to have beneficial effects on fish abundance and diversity in the Sierra Nevada, to stabilize stream incision in montane meadows, and to reduce discharge of nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment loads into fragile water bodies such as Lake Tahoe. -

Plumas National Forest EA EIS CE

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2008 to 06/30/2008 Plumas National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Aerial Application of Fire - Fuels management Completed Actual: 02/18/2008 10/2007 Christopher Wehrli Retardant 10/11/2007 202-205-1332 EA [email protected] Description: The Forest Service proposes to continue the aerial application of fire retardant to fight fires on National Forest System lands. An environmental analysis will be conducted to prepare an Environmental Assessment on the proposed action. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/retardant/index.html Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Nation Wide. National Forest System Land - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:03/2008 03/2008 Gina Owens Management Planning - Orders FEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-205-1187 Proposed Rule 02/15/2008 [email protected] EIS Description: The Agency proposes to publish a rule at 36 CFR part 219 to finish rulemaking on the land management planning rule issued on January 5, 2005 (2005 rule). The 2005 rule guides development, revision, and amendment of land management plans. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/emc/nfma/2008_planning_rule.html Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - All units of the National Forest System. Agency-wide. Plumas National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R5 - Pacific Southwest Region Backcountry Discovery Trail - Recreation management Completed Actual: 01/24/2008 08/2008 Peggy Gustafson CE 530-283-7620 [email protected] Description: Designation of Backcountry Discovery Trail (BCDT) on existing roads within the Plumas National Forest to tie together statewide motorized trail Location: UNIT - Plumas National Forest All Units. -

Final Report

Deliverable 3.10 Final Report Red Clover/McReynolds Creek Restoration Project Agreement Number 04-116-555-01 Feather River Coordinated Resource Management - Plumas Corporation January 28, 2008 Plumas Corporation SWRCB Grant Agreement No.04-116-555-0 2 Background The Red Clover/McReynolds Creek Restoration Project encompasses a 775-acre area, covering 715 acres of privately owned land and 60 acres of public land on Plumas National Forest (PNF). This portion of Red Clover Creek drains a watershed area of 84 square miles, and is a tributary to Indian Creek and ultimately, the East Branch North Fork Feather River. The watershed has been historically used for grazing and logging with an extensive road and historic logging railroad grade system. The combination of road-like features and historic grazing along with a 1950’s-era beaver eradication effort, initiated moderate to severe incision (downcutting) of the stream channels throughout Red Clover Valley, resulting in extensive gully networks that have lowered the shallow groundwater tables in the valley meadow, concurrently changing the plant communities from mesic species to xeric species such as sage, and increasing the sediment supply. This in turn has resulted in a loss of meadow productivity, diminished summer flows, and severe bank erosion. Due to severe channel incision and bank erosion, the Red Clover Creek Watershed channel system was determined to be the third highest sediment-producing subwatershed in the East Branch North Fork Feather River watershed (EBNFFR Erosion Inventory Report, USDA- Soil Conservation Service, 1989). Prior to project implementation remnants of the original meadow vegetative community occurred only near springs, hill slope sub-flow zones, and in gully bottoms. -

Martis Valley Community Plan

MARTIS VALLEY COMMUNITY PLAN Adopted by the Board of Supervisors December 16, 2003 MARTIS VALLEY COMMUNITY PLAN Prepared by: PLACER COUNTY WITH ASSISTANCE FROM: Pacific Municipal Consultants LSC Associates Placer County Water Agency Adopted by the Board of Supervisors December 16, 2003 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Board of Supervisors Bill Santucci ............................................................................................................................... District 1 Robert Weygandt ........................................................................................................................ District 2 Harriet White .............................................................................................................................. District 3 Ted Gaines ................................................................................................................................. District 4 Rex Bloomfield .......................................................................................................................... District 5 Contact: 175 Fulweiler Avenue, Auburn, CA 95603 (530) 889-4010 Fax (530) 889-4009 www.placer.ca.gov/bos ________________________________________________________________________________ Planning Commission Noe Fierros ................................................................................................................................. District 1 Ken Denio ................................................................................................................................. -

Martis Valley Groundwater Basin Bulletin 118

North Lahontan Hydrologic Region California’s Groundwater Martis Valley Groundwater Basin Bulletin 118 Martis Valley Groundwater Basin • Groundwater Basin Number: 6-67 • County: Nevada, Placer • Surface Area: 35,600 acres (57 square miles) Basin Boundaries and Hydrology The Martis Valley Groundwater Basin is an intermontane, fault-bounded basin east of the Sierra Nevada crest. The Martis Valley is the principal topographic feature within the Basin, although the Basin extends to the north and west of the well-defined valley. The floor of Martis Valley is terraced with elevations between 5,700 and 5,900 feet above mean sea level. The valley is punctuated by round hills rising 1,000 feet or more around the valley perimeter. Mountains along the southern margin of Martis Valley rise dramatically to elevation in excess of 8,000 feet mean sea level. The basin boundaries are based on detailed field investigations developed by Hydro Search Inc. (1975). The Truckee River crosses the basin from south to east in a shallow, incised channel. Principal tributaries to the Truckee River are Donner Creek, Martis Creek, and Prosser Creek. Major surface water storage reservoirs include Donner Lake, Martis Creak Lake, and Prosser Creek Reservoir. Average precipitation is estimated to be 23 inches in the lower elevations of the eastern portion of the basin to nearly 40 inches in the western areas. Hydrogeologic Information Water Bearing Formations The following summary of water bearing formations is from Nimbus Engineers (2001). Basement Rocks. Basement rocks include all rock units older than the basin- fill sediments and interlayered basin-fill volcanic units, specifically Cretaceous-Jurassic plutonic and metamorphic rocks and Miocene volcanic units. -

Chapter 3 Region Description

Region Description CHAPTER 3.0 REGION DESCRIPTION 3.1 Introduction The Upper Feather River watershed encompasses 2.3 million acres in the northern Sierra Nevada, where that range intersects the Cascade Range to the north and the Diamond Mountains of the Great Basin and Range Province to the east. The watershed drains generally southwest to Lake Oroville, the largest reservoir of the California State Water Project (SWP). Water from Lake Oroville enters a comprehensive system of natural and constructed conveyances to provide irrigation and domestic water as well as to supply natural aquatic ecosystems in the Lower Feather River, Sacramento River, and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. Lake Oroville is the principal storage facility of the SWP, which delivers water to over two- thirds of California’s population and provides an average of 34.3 million acre-feet (AF)/year of agricultural water to the Central Valley. Lands to the east of the Upper Feather River watershed drain to Eagle and Honey Lakes that are closed drainage basins in the Basin and Range Province, while lands to the north, west, and south drain to the Sacramento River via the Pit River, Yuba River, Battle Creek, Thomas Creek, Big Chico Creek, and Butte Creek. Mount Lassen, the southernmost volcano in the Cascade Range, defines the northern boundary of the region. Sierra Valley, the largest valley in the Sierra Nevada, defines the southern boundary. At the intersection of the Great Basin, the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and the Cascade Range, the Region supports a diversity of habitats including an assemblage of meadows and alluvial valleys interconnected by river gorges and rimmed by granite and volcanic mountains.