Chapter 3 Region Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Center Comments to the California Department of Fish and Game

July 24, 2006 Ryan Broderick, Director California Department of Fish and Game 1416 Ninth Street, 12th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Improving efficiency of California’s fish hatchery system Dear Director Broderick: On behalf of the Pacific Rivers Council and Center for Biological Diversity, we are writing to express our concerns about the state’s fish hatchery and stocking system and to recommend needed changes that will ensure that the system does not negatively impact California’s native biological diversity. This letter is an update to our letter of August 31, 2005. With this letter, we are enclosing many of the scientific studies we relied on in developing this letter. Fish hatcheries and the stocking of fish into lakes and streams cause numerous measurable, significant environmental effects on California ecosystems. Based on these impacts, numerous policy changes are needed to ensure that the Department of Fish and Game’s (“DFG”) operation of the state’s hatchery and stocking program do not adversely affect California’s environment. Further, as currently operated, the state’s hatchery and stocking program do not comply with the California Environmental Quality Act, Administrative Procedures Act, California Endangered Species Act, and federal Endangered Species Act. The impacts to California’s environment, and needed policy changes to bring the state’s hatchery and stocking program into compliance with applicable state and federal laws, are described below. I. FISH STOCKING NEGATIVELY IMPACTS CALIFORNIA’S NATIVE SALMONIDS, INCLUDING THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES Introduced salmonids negatively impact native salmonids in a variety of ways. Moyle, et. al. (1996) notes that “Introduction of non-native fish species has also been the single biggest factor associated with fish declines in the Sierra Nevada.” Moyle also notes that introduced species are contributing to the decline of 18 species of native Sierra Nevada fish species, and are a major factor in the decline of eight of those species. -

DONNER LAKE - AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES MANDATORY SELF-INSPECTION LAUNCH CERTIFICATE PERMIT Town of Truckee Ordinance 2020-03 Chapter 14.01

DONNER LAKE - AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES MANDATORY SELF-INSPECTION LAUNCH CERTIFICATE PERMIT Town of Truckee Ordinance 2020-03 Chapter 14.01 Must Complete, sign, and date this Launch Certification Permit and keep in the vessel. If this is the first inspection of the year, the owner or operator of the vessel shall submit a self-inspection form to the Town of Truckee and obtain an inspection sticker for the vessel. *All motorized watercraft STILL require an inspection before launching into Donner Lake. Non-motorized watercraft are also capable of transporting aquatic invasive species. It is highly recommended to complete a self-inspection on all watercraft. Vessel Registration Number: Zip Code: Date: Boat Type (circle one): Ski/Wake Sail PWC/Jet Ski Fishing Pleasure Boat Wooden Non-Moto Other: Last Waterbody visited with this watercraft: 1. Is your vessel, trailer and all equipment clean of all mud, dirt, plants, fish or animals and drained of all water including all bilge areas, fresh-water cooling systems, lower outboard units, ballast tanks, live-wells, buckets, etc. and completely dry? YES, my vessel is Clean, Drain and Dry No, my vessel is NOT Clean, Drain and Dry. Vessel must be cleaned, drained and completely dry before it will be permitted to launch. Do not clean or drain your vessel by the lake or at the launch ramp. See below for details on how to properly clean your vessel and equipment prior to launching. 2. Has your vessel been in any of the infested waters listed on the back page of this form within the last 30 days? YES, my vessel has been in an infested body of water: Go to question 3 No, my vessel has NOT been in an infested body of water: You are ready to launch. -

Lake Tahoe Geographic Response Plan

Lake Tahoe Geographic Response Plan El Dorado and Placer Counties, California and Douglas and Washoe Counties, and Carson City, Nevada September 2007 Prepared by: Lake Tahoe Response Plan Area Committee (LTRPAC) Lake Tahoe Geographic Response Plan September 2007 If this is an Emergency… …Involving a release or threatened release of hazardous materials, petroleum products, or other contaminants impacting public health and/or the environment Most important – Protect yourself and others! Then: 1) Turn to the Immediate Action Guide (Yellow Tab) for initial steps taken in a hazardous material, petroleum product, or other contaminant emergency. First On-Scene (Fire, Law, EMS, Public, etc.) will notify local Dispatch (via 911 or radio) A complete list of Dispatch Centers can be found beginning on page R-2 of this plan Dispatch will make the following Mandatory Notifications California State Warning Center (OES) (800) 852-7550 or (916) 845-8911 Nevada Division of Emergency Management (775) 687-0300 or (775) 687-0400 National Response Center (800) 424-8802 Dispatch will also consider notifying the following Affected or Adjacent Agencies: County Environmental Health Local OES - County Emergency Management Truckee River Water Master (775) 742-9289 Local Drinking Water Agencies 2) After the Mandatory Notifications are made, use Notification (Red Tab) to implement the notification procedures described in the Immediate Action Guide. 3) Use the Lake Tahoe Basin Maps (Green Tab) to pinpoint the location and surrounding geography of the incident site. 4) Use the Lake and River Response Strategies (Blue Tab) to develop a mitigation plan. 5) Review the Supporting Documentation (White Tabs) for additional information needed during the response. -

Sacramento and Feather Rivers and Their Tributaries, Sacramento Slough and Sutter Bypass

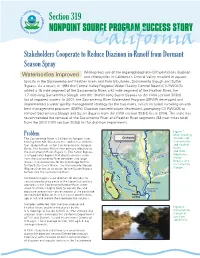

Section 319 NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM SUCCESS STORY Stakeholders Cooperate to ReduceCalifornia Diazinon in Runoff from Dormant Season Spray Widespread use of the organophosphate (OP) pesticides diazinon Waterbodies Improved and chlorpyrifos in California’s Central Valley resulted in aquatic toxicity in the Sacramento and Feather rivers and their tributaries, Sacramento Slough and Sutter Bypass. As a result, in 1994 the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board (CV-RWQCB) added a 16-mile segment of the Sacramento River, a 42-mile segment of the Feather River, the 1.7-mile-long Sacramento Slough, and the 19-mile-long Sutter Bypass to the CWA section 303(d) list of impaired waters. In 2001, the Sacramento River Watershed Program (SRWP) developed and implemented a water quality management strategy for the two rivers, which included installing on-site best management practices (BMPs). Diazinon concentrations decreased, prompting CV-RWQCB to remove Sacramento Slough and Sutter Bypass from the CWA section 303(d) list in 2006. The state has recommended the removal of the Sacramento River and Feather River segments (58 river miles total) from the 2010 CWA section 303(d) list for diazinon impairments. UV162 Figure 1. Problem Map showing The Sacramento River is California’s longest river, Orchards locations of flowing from Mt. Shasta to the confluence with the Sacramento San Joaquin River at the Sacramento-San Joaquin and Feather UV45 Delta. The Feather River is the primary tributary to h rivers g l o u C S and their the Sacramento River (Figure 1). The Sutter Bypass o Colusa k r l e tributaries, u c i v is a floodwater bypass that diverts excess water a R s J a b Sutter from the Sacramento River between two large a Sutter u Y S 30 u UV B S Co. -

Storm Water Resource Plan | May 2018 Final

AMERICAN RIVER BASIN Storm Water Resource Plan | May 2018 Final Funding for this project has been provided in full or in part through an agreement with the State Water Resources Control Board using funds from Proposition 1. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the foregoing, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. American River Basin Storm Water Resource Plan – Final Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Intent and Content ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Goals and Objectives ............................................................................................................. 2 2.0 WATERSHED IDENTIFICATION ............................................................................................... 3 2.1 Watershed Boundaries (IRWMP Section 2.1) ..................................................................... 3 2.2 Internal Boundaries (IRWMP Sections 2.2, 2.8, & 2.9) ...................................................... 5 2.3 Water and Environmental Resources (IRWMP Sections 2.6.2, 2.6.3, & 2.8) ................. 11 2.4 Natural Watershed Processes (IRWMP Sections 2.6.1, 2.6.2, & 2.6.3) ........................... 13 2.5 Watershed Issues and Priorities (IRWMP Sections 2.6.2, 2.7 to 2.9, & Apdx. B) ......... -

San Luis Unit Project History

San Luis Unit West San Joaquin Division Central Valley Project Robert Autobee Bureau of Reclamation Table of Contents The San Luis Unit .............................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................4 Project Authorization.....................................................7 Construction History .....................................................9 Post Construction History ................................................19 Settlement of the Project .................................................24 Uses of Project Water ...................................................25 1992 Crop Production Report/Westlands ....................................27 Conclusion............................................................28 Suggested Readings ...........................................................28 Index ......................................................................29 1 The West San Joaquin Division The San Luis Unit Approximately 300 miles, and 30 years, separate Shasta Dam in northern California from the San Luis Dam on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley. The Central Valley Project, launched in the 1930s, ascended toward its zenith in the 1960s a few miles outside of the town of Los Banos. There, one of the world's largest dams rose across one of California's smallest creeks. The American mantra of "bigger is better" captured the spirit of the times when the San Luis Unit -

Southern Sonoma County Stormwater Resources Plan Evaluation Process

Appendix A List of Stakeholders Engaged APPENDIX A List of Stakeholders Engaged Specific audiences engaged in the planning process are identified below. These audiences include: cities, government officials, landowners, public land managers, locally regulated commercial, agricultural and industrial stakeholders, non-governmental organizations, mosquito and vector control districts and the general public. TABLE 1 LIST OF STAKEHOLDERS ENGAGED Organization Type Watershed 1st District Supervisor Government Sonoma 5th District Supervisor Government Petaluma City of Petaluma Government Petaluma City of Sonoma Government Sonoma Daily Acts Non-Governmental Petaluma Friends of the Petaluma River Non-Governmental Petaluma Zone 2A Petaluma River Watershed- Flood Control Government Petaluma Advisory Committee Zone 3A Valley of the Moon - Flood Control Advisory Government Sonoma Committee Marin Sonoma Mosquito & Vector Control District Special District Both Sonoma Ecology Center Non-Governmental Sonoma Sonoma County Regional Parks Government Both Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Government Both Space District Sonoma Land Trust Non-Governmental Both Sonoma County Transportation and Public Works Government Both Valley of the Moon Water District Government Sonoma Sonoma Resource Conservation District Special District Both Sonoma County Permit Sonoma Government Both Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Non-Governmental N/A California State Parks Government Both California State Water Resources Control Board Government N/A Southern Sonoma -

AQ Conformity Amended PBA 2040 Supplemental Report Mar.2018

TRANSPORTATION-AIR QUALITY CONFORMITY ANALYSIS FINAL SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT Metropolitan Transportation Commission Association of Bay Area Governments MARCH 2018 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Jake Mackenzie, Chair Dorene M. Giacopini Julie Pierce Sonoma County and Cities U.S. Department of Transportation Association of Bay Area Governments Scott Haggerty, Vice Chair Federal D. Glover Alameda County Contra Costa County Bijan Sartipi California State Alicia C. Aguirre Anne W. Halsted Transportation Agency Cities of San Mateo County San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission Libby Schaaf Tom Azumbrado Oakland Mayor’s Appointee U.S. Department of Housing Nick Josefowitz and Urban Development San Francisco Mayor’s Appointee Warren Slocum San Mateo County Jeannie Bruins Jane Kim Cities of Santa Clara County City and County of San Francisco James P. Spering Solano County and Cities Damon Connolly Sam Liccardo Marin County and Cities San Jose Mayor’s Appointee Amy R. Worth Cities of Contra Costa County Dave Cortese Alfredo Pedroza Santa Clara County Napa County and Cities Carol Dutra-Vernaci Cities of Alameda County Association of Bay Area Governments Supervisor David Rabbit Supervisor David Cortese Councilmember Pradeep Gupta ABAG President Santa Clara City of South San Francisco / County of Sonoma San Mateo Supervisor Erin Hannigan Mayor Greg Scharff Solano Mayor Liz Gibbons ABAG Vice President City of Campbell / Santa Clara City of Palo Alto Representatives From Mayor Len Augustine Cities in Each County City of Vacaville -

Sierra Nevada Framework FEIS Chapter 3

table of contrents Sierra Nevada Forest Plan Amendment – Part 4.6 4.6. Vascular Plants, Bryophytes, and Fungi4.6. Fungi Introduction Part 3.1 of this chapter describes landscape-scale vegetation patterns. Part 3.2 describes the vegetative structure, function, and composition of old forest ecosystems, while Part 3.3 describes hardwood ecosystems and Part 3.4 describes aquatic, riparian, and meadow ecosystems. This part focuses on botanical diversity in the Sierra Nevada, beginning with an overview of botanical resources and then presenting a more detailed analysis of the rarest elements of the flora, the threatened, endangered, and sensitive (TES) plants. The bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), lichens, and fungi of the Sierra have been little studied in comparison to the vascular flora. In the Pacific Northwest, studies of these groups have received increased attention due to the President’s Northwest Forest Plan. New and valuable scientific data is being revealed, some of which may apply to species in the Sierra Nevada. This section presents an overview of the vascular plant flora, followed by summaries of what is generally known about bryophytes, lichens, and fungi in the Sierra Nevada. Environmental Consequences of the alternatives are only analyzed for the Threatened, Endangered, and Sensitive plants, which include vascular plants, several bryophytes, and one species of lichen. 4.6.1. Vascular plants4.6.1. plants The diversity of topography, geology, and elevation in the Sierra Nevada combine to create a remarkably diverse flora (see Section 3.1 for an overview of landscape patterns and vegetation dynamics in the Sierra Nevada). More than half of the approximately 5,000 native vascular plant species in California occur in the Sierra Nevada, despite the fact that the range contains less than 20 percent of the state’s land base (Shevock 1996). -

Appendix H. Lake Davis, CA, Rotenone Application

Appendix H. Lake Davis, CA, Rotenone Application The information contained in this summary was provided by the California Department of Fish and Game (California Department of Fish and Game, 1999). In October 1997, the California Department of Fish and Game treated Lake Davis in Plumas County, California, with rotenone to eliminate introduced Northern pike (Esox lucius) that was considered a predatory fish, potentially threatening indigenous salmonids and other threatened and endangered fish species in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (personal communication: Brian Finlayson, California Department of Fish and Game 2005). Located at an elevation of 5,775 ft above mean sea level, Lake Davis is a 4,026 acre (1,619 ha) impoundment of Big Grizzly Creek, a tributary to the Middle Fork Feather River. The reservoir has a maximum depth of 108 ft (33 m) and a mean depth of 20.5 ft (6.3 m) (Lee, 2001). The reservoir is classified as meso-eutrophic based on growing season inorganic nitrogen concentration (Lee, 2001). From October 15 - 16, 1997, the Lake Davis and its tributaries (Grizzly, Freeman and Cow Creeks) were treated with two formulations of rotenone, i.e., 64,000 lbs of powdered ProNoxfish (7.1% a.i.; EPA Registration No. 432-829) and 15,785 gallons of a synergized liquid formulation Nusyn-Noxfish (2.5% a.i.; EPA Registration No. 432-550) to maintain a desired treatment concentration. The liquid formulation used piperonyl butoxide as a synergist. Rotenone concentrations were measured within and surrounding the treatment area. The data suggest that initially rotenone was not equally distributed through the water column; this is consistent with the reservoir having an average depth of roughly 20 feet. -

11404500 North Fork Feather River at Pulga, CA Sacramento River Basin

Water-Data Report 2011 11404500 North Fork Feather River at Pulga, CA Sacramento River Basin LOCATION.--Lat 39°47′40″, long 121°27′02″ referenced to North American Datum of 1927, in SE ¼ NE ¼ sec.6, T.22 N., R.5 E., Butte County, CA, Hydrologic Unit 18020121, Plumas National Forest, on left bank between railroad and highway bridges, 0.6 mi downstream from Flea Valley Creek and Pulga, and 1.6 mi downstream from Poe Dam. DRAINAGE AREA.--1,953 mi². SURFACE-WATER RECORDS PERIOD OF RECORD.--October 1910 to current year. Monthly discharge only for some periods and yearly estimates for water years 1911 and 1938, published in WSP 1315-A. Prior to October 1960, published as "at Big Bar." CHEMICAL DATA: Water years 1963-66, 1972, 1977. WATER TEMPERATURE: Water years 1963-83. REVISED RECORDS.--WSP 931: 1938 (instantaneous maximum discharge), 1940. WSP 1515: 1935. WDR CA-77-4: 1976 (yearly summaries). GAGE.--Water-stage recorder. Datum of gage is 1,305.62 ft above NGVD of 1929. Prior to Oct. 1, 1937, at site 1.1 mi upstream at different datum. Oct. 1, 1937, to Sept. 30, 1958, at present site at datum 5.00 ft higher. COOPERATION.--Records, including diversion to Poe Powerplant (station 11404900), were collected by Pacific Gas and Electric Co., under general supervision of the U.S. Geological Survey, in connection with Federal Energy Regulatory Commission project no. 2107. REMARKS.--Flow regulated by Lake Almanor, Bucks Lake, Butt Valley Reservoir (stations 11399000, 11403500, and 11401050, respectively), Mountain Meadows Reservoir, and five forebays, combined capacity, 1,386,000 acre-ft. -

ERP Directed Actions Northern Pike Containment System at Lake Davis

ERP DIRECTED ACTIONS Northern Pike Containment System at Lake Davis Reference Ecosystem Restoration Program Prop 50 Bond Funded Project No. DFG-05#### Prepared by: Leslie Pierce Department of Water Resources Fish Passage Improvement Program 901 P Street, P.O. Box 942836 Sacramento CA 94236 (916) 651-9630 CALFED BAY-DELTA PROGRAM Ecosystem Restoration Program Directed Action Proposal PART A. Cover Sheet A1. Proposal Title: Northern Pike Containment System at Lake Davis A2. Lead Applicant or Organization: Contact Name: Leslie Pierce Address: Department of Water Resources (DWR), Fish Passage Improvement Program, P.O. Box 942836, Sacramento CA 94236 Phone Number: (916) 651-9630 Fax Number: (916) 651-9607 E-mail: [email protected] A3. Project Manager or Principal Investigator Contact Name: David Panec Agency/Organization Affiliation: DWR, Operations and Maintenance Address: P. O. Box 942836, Sacramento, CA 94236 Phone Number: (916) 653-0772 Fax Number: (916) 654-5554 E-mail: [email protected] A4. Cost of Project: Request for new ERP Prop 50 funding: $2,000,000. Full project cost is $4.26 million. A5. Cost Share Partners: 1) Fish Passage Improvement Program Total Cost Share: $260,000 Department of Water Resources Type: Cash Leslie Pierce, Senior Environmental Scientist P.O. Box 942836 Sacramento CA 94236-0001 Phone: (916) 651-9630 Fax: (916) 651-9607 [email protected] 2) Division of Operations and Maintenance Total Cost Share: $2.0 million Oroville Field Division Type: Cash Department of Water Resources Maury Miller 460 Glen Drive Oroville, CA. 95966 Phone: (530) 534-2425 Fax: (530) 534-2420 [email protected] Page 2 of 22 CALFED BAY-DELTA PROGRAM Ecosystem Restoration Program Directed Action Proposal A6.