Active and Potentially Active Faults in Or Near the Alaska Highway Corridor, Dot Lake to Tetlin Junction, Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction San Andreas Fault: an Overview

Introduction This volume is a general geology field guide to the San Andreas Fault in the San Francisco Bay Area. The first section provides a brief overview of the San Andreas Fault in context to regional California geology, the Bay Area, and earthquake history with emphasis of the section of the fault that ruptured in the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. This first section also contains information useful for discussion and making field observations associated with fault- related landforms, landslides and mass-wasting features, and the plant ecology in the study region. The second section contains field trips and recommended hikes on public lands in the Santa Cruz Mountains, along the San Mateo Coast, and at Point Reyes National Seashore. These trips provide access to the San Andreas Fault and associated faults, and to significant rock exposures and landforms in the vicinity. Note that more stops are provided in each of the sections than might be possible to visit in a day. The extra material is intended to provide optional choices to visit in a region with a wealth of natural resources, and to support discussions and provide information about additional field exploration in the Santa Cruz Mountains region. An early version of the guidebook was used in conjunction with the Pacific SEPM 2004 Fall Field Trip. Selected references provide a more technical and exhaustive overview of the fault system and geology in this field area; for instance, see USGS Professional Paper 1550-E (Wells, 2004). San Andreas Fault: An Overview The catastrophe caused by the 1906 earthquake in the San Francisco region started the study of earthquakes and California geology in earnest. -

Denali Fault System of Southern Alaska an Interior Strikeslip

TECTONICS, VOL. 12, NO. 5, PAGES 1195-1208, OCTOBER 1993 DENALl FAULT SYSTEM OF SOUTHERN 1974; Lanphere,1978; Stoutand Chase,1980]. Despitethis ALASKA: AN INTERIOR STRIKE.SLIP consensus,the tectonichistory of the DFS remainsrelatively STRUCTURE RESPONDING TO DEXTRAL unconstrained.Critical outcrops are rare, access is difficult,and AND SINISTRAL SHEAR COUPLING to this day muchof the regionis incompletelymapped at detailed scales. Grantz[1966] named or redefinedsix individualfault ThomasF. Redfieldand Paul G. Fitzgerald1 segmentscomprising the DFS. From west to eastthe Departmentof Geology,Arizona State University, segmentsare the Togiak/Tikchikfault, the Holitnafault, the Tempe Farewellfault, the Denali fault (subdividedinto the McKinley andHines Creek strands), the Shakwakfault, andthe Dalton fault (Figure 1). At its westernend, the DFS is mappednot as a singleentity but ratherappears to splayinto a complex, Abstract.The Denalifault system (DFS) extendsfor-1200 poorlyexposed set of crosscuttingfault patterns[Beikman, km, from southeastto southcentral Alaska. The DFS has 1980]. Somewhatmore orderly on its easternend, the DFS beengenerally regarded as a fight-lateralstrike-slip fault, along appearsto join forceswith the ChathamStrait fault. This which postlate Mesozoicoffsets of up to 400 km havebeen structurein turn is truncatedby the Fairweatherfault [Beikman, suggested.The offsethistory of the DFS is relatively 1980],the present-dayNorth American plate Pacific plate unconstrained,particularly at its westernend. For thisstudy boundary[Plafker -

Western States Seismic Policy Council Policy Recommendation 18-3

WESTERN STATES SEISMIC POLICY COUNCIL POLICY RECOMMENDATION 18-3 Definitions of Recency of Surface Faulting for the Basin and Range Province Policy Recommendation 18-3 WSSPC recommends that each state in the Basin and Range physiographic province (BRP), through consultation with state and federal geological surveys and other earthquake-hazard experts, define scientifically and societally relevant categories for recency of surface faulting (generally earthquake magnitude ≥M 6.5). WSSPC further recommends that in the absence of information to the contrary, all Quaternary faults be considered to have the recency of activity documented in the USGS Quaternary fault and fold database until more adequate data can be developed. Executive Summary Fault recency definitions are limited to the Quaternary because this period of geologic time is considered by the scientific community to be most relevant to paleoseismic studies of earthquake faults (Machette and others, 2004). The recency class of a fault is the youngest class based on the demonstrated age of most recent surface faulting. Latest Pleistocene-Holocene faults are included within the definition of late Quaternary faults, and both latest Pleistocene-Holocene and late Quaternary faults are included in Quaternary faults. Establishment/definition of surface-faulting recency categories are based on the ways that faults are portrayed on geologic maps and on the availability of geologic data in the BRP. Policy makers (owners, regulators, governmental agencies) should consult with state and federal geological surveys and other earthquake-hazard experts in using these recency categories and additional geologic data in developing definitions of hazardous faults to be considered in planning for development or infrastructure projects. -

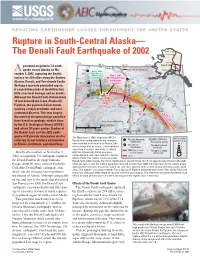

Rupture in South-Central Alaska— the Denali Fault Earthquake of 2002

REDUCING EARTHQUAKE LOSSES THROUGHOUT THE UNITED STATES Rupture in South-Central Alaska— ������� ��� The Denali Fault Earthquake of 2002 ��� �������� � � � � � � ��� ��������� �� ����� powerful magnitude 7.9 earth- ����� ����� ����� ���� �� ��� ������ quake struck Alaska on No- ����� ������������ ��� �������� ��������� A ��� ��� ���� � ���� ������ ������ � � � vember 3, 2002, rupturing the Earth’s � � �������� ��� �� ���� � � � � surface for 209 miles along the Susitna � ���������� ���� ������ ����� � � ����� � � ���������� Glacier, Denali, and Totschunda Faults. � � ����� � � � ��������� �� � � � � � Striking a sparsely populated region, � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � it caused thousands of landslides but � � � � � � � � � � little structural damage and no deaths. � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � Although the Denali Fault shifted about � �������� ������� � � ��� � � � � ������� � � 14 feet beneath the Trans-Alaska Oil ��������� �� � ����� � Pipeline, the pipeline did not break, � � ���� � � � � � � ������ � � � � � � � � �������� averting a major economic and envi- � � ���� � ��������� �� � ronmental disaster. This was largely � � � � � � � the result of stringent design specifica- � � � � � � � � tions based on geologic studies done ������������ ��� �������� � � � � � � � by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) � �� ��� ���������� � � � and others 30 years earlier. Studies of � � � � � � � � � � �� ����� � � ���������� � � � ���� the Denali Fault and the 2002 earth- � quake will provide information vital to The November 3, 2002, magnitude -

Late Quaternary Faulting in the Kaikoura Region, Southeastern Marlborough, New Zealand

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Russell J. Van Dissen for the degree of Master of Science in Geology presented on February 15, 1989. Title: Late Quaternary Faulting in the Kaikoura Region, Southeastern Marlborough, New Zealand Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Dr. Robert 8.0eats Active faults in the Kaikoura region include the Hope, Kekerengu, and Fidget Faults, and the newly discovered Jordan Thrust, Fyffe, and Kowhai Faults. Ages of faulted alluvial terraces along the Hope Fault and the Jordan Thrust were estimated using radiocarbon-calibrated weathering-rind measurements on graywacke clasts. Within the study area, the Hope Fault is divided, from west to east, into the Kahutara, Mt. Fyffe, and Seaward segments. The Kahutara segment has a relatively constant Holocene right-lateral slip rate of 20-32 mm/yr, and an earthquake recurrence interval of 86 to 600 yrs: based on single-event displacements of 3 to 12 m. The western portion of the Mt. Fyffe segment has a minimum Holocene lateral slip rate of 16 + 5 mm/yr .(southeast side up); the eastern portion has horizontal and vertical slip rates of 4.8+ 2.7 mm/yr and 1.7 + 0.2 mm/yr, respectively (northwest side up). There is no dated evidence for late Quaternary movementon the Seaward segment, and its topographic expression is much more subdued than that of the two western segments. The Jordan Thrust extends northeast from the Hope Fault, west of the Seaward segment. The thrust has horizontal and vertical slip rates of 2.2 + 1.3 mm/yr and 2.1 + 0.5 mm/yr, respectively (northwest side up), and a maximum recurrence interval of 1200 yrs: based on 3 events within the last 3.5 ka. -

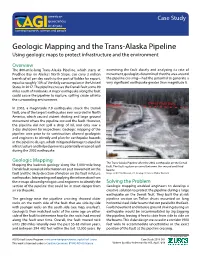

Geologic Mapping and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Using Geologic Maps to Protect Infrastructure and the Environment

Case Study Geologic Mapping and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Using geologic maps to protect infrastructure and the environment Overview The 800-mile-long Trans-Alaska Pipeline, which starts at examining the fault closely and analyzing its rate of Prudhoe Bay on Alaska’s North Slope, can carry 2 million movement, geologists determined that the area around barrels of oil per day south to the port of Valdez for export, the pipeline crossing—had the potential to generate a equal to roughly 10% of the daily consumption in the United very significant earthquake greater than magnitude 8. States in 2017. The pipeline crosses the Denali fault some 90 miles south of Fairbanks. A major earthquake along the fault could cause the pipeline to rupture, spilling crude oil into the surrounding environment. Denali Fault Trace In 2002, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake struck the Denali fault, one of the largest earthquakes ever recorded in North America, which caused violent shaking and large ground movement where the pipeline crossed the fault. However, the pipeline did not spill a drop of oil, and only saw a 3-day shutdown for inspections. Geologic mapping of the pipeline area prior to its construction allowed geologists and engineers to identify and plan for earthquake hazards in the pipeline design, which mitigated damage to pipeline infrastructure and helped prevent a potentially major oil spill during the 2002 earthquake. Geologic Mapping The Trans-Alaska Pipeline after the 2002 earthquake on the Denali Mapping the bedrock geology along the 1,000-mile-long fault. The fault rupture occurred between the second and third Denali fault revealed information on past movement on the beams fault and the likely direction of motion on the fault in future Image credit: Tim Dawson, U.S. -

Magnitude Limits of Subduction Zone Earthquakes

Magnitude Limits of Subduction Zone Earthquakes Rong, Y., Jackson, D. D., Magistrale, H., Goldfinger, C. (2014). Magnitude Limits of Subduction Zone Earthquakes. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 104(5), 2359-2377. doi:10.1785/0120130287 10.1785/0120130287 Seismological Society of America Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America This copy is for distribution only by the authors of the article and their institutions in accordance with the Open Access Policy of the Seismological Society of America. For more information see the publications section of the SSA website at www.seismosoc.org THE SEISMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA 400 Evelyn Ave., Suite 201 Albany, CA 94706-1375 (510) 525-5474; FAX (510) 525-7204 www.seismosoc.org Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 104, No. 5, pp. 2359–2377, October 2014, doi: 10.1785/0120130287 Magnitude Limits of Subduction Zone Earthquakes by Yufang Rong, David D. Jackson, Harold Magistrale, and Chris Goldfinger Abstract Maximum earthquake magnitude (mx) is a critical parameter in seismic hazard and risk analysis. However, some recent large earthquakes have shown that most of the existing methods for estimating mx are inadequate. Moreover, mx itself is ill-defined because its meaning largely depends on the context, and it usually cannot be inferred using existing data without associating it with a time interval. In this study, we use probable maximum earthquake magnitude within a time period of interest, m T m m T p , to replace x. The term p contains not only the information of magnitude m T limit but also the occurrence rate of the extreme events. -

Dynamic Response of Bridges to Near-Fault Forward Directivity Ground

Research Report Agreement 355270, Task 6 Near-Fault Ground Motions DYNAMIC RESPONSE OF BRIDGES TO NEAR-FAULT, FORWARD DIRECTIVITY GROUND MOTIONS by Adrian Rodriguez-Marek William Cofer Associate Professor Professor Civil and Environmental Engineering Department Washington State University Pullman, WA 99164 Washington State Transportation Center (TRAC) Washington State University Civil & Environmental Engineering PO Box 642910 Pullman, WA 99164-2910 Washington State Department of Transportation Technical Monitor Kim Willoughby Research Manager Materials and Construction, Bridges and Structures and Maintenance Prepared for Washington State Transportation Commission Department of Transportation and in cooperation with U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration December 2007 1. REPORT NO. 2. GOVERNMENT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. WA-RD 689.1 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE DYNAMIC RESPONSE OF BRIDGES TO NEAR-FAULT, December 2007 FORWARD DIRECTIVITY GROUND MOTIONS 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR(S) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Adrian Rodriguez-Marek and William Cofer 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NO. Washington State Transportation Center (TRAC) Washington State University, Civil & Environmental Engineering 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. PO Box 642910 WSDOT 355270, Task 6 Pullman, WA 99164-2910 12. SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED Research Office Washington State Department of Transportation Research Report Transportation Building, MS 47372 Olympia, Washington 98504-7372 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES This study was conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. 16. ABSTRACT Research over the last decade has shown that pulse-type earthquake ground motions that result from forward- directivity (FD) effects can result in significant damage to structures. -

Diverse Rupture Modes for Surface-Deforming Upper Plate Earthquakes in the Southern Puget Lowland of Washington State

Diverse rupture modes for surface-deforming upper plate earthquakes in the southern Puget Lowland of Washington State Alan R. Nelson1,*, Stephen F. Personius1, Brian L. Sherrod2, Harvey M. Kelsey3, Samuel Y. Johnson4, Lee-Ann Bradley1, and Ray E. Wells5 1Geologic Hazards Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, MS 966, PO Box 25046, Denver, Colorado 80225, USA 2U.S. Geological Survey at Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Box 351310, Seattle, Washington 98195, USA 3Department of Geology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521, USA 4Western Coastal and Marine Geology Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 400 Natural Bridges Drive, Santa Cruz, California 95060, USA 5Geology, Minerals, Energy, and Geophysics Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, MS 973, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA ABSTRACT earthquakes. In the northeast-striking Saddle migrating forearc has deformed the Seto Inland Mountain deformation zone, along the west- Sea into a series of basins and uplifts bounded Earthquake prehistory of the southern ern limit of the Seattle and Tacoma fault by faults. One of these, the Nojima fault, pro- Puget Lowland, in the north-south com- zones, analysis of previous ages limits earth- duced the 1995 Mw6.9 Hyogoken Nanbu (Kobe) pressive regime of the migrating Cascadia quakes to 1200–310 cal yr B.P. The prehistory earthquake, which killed more than 6400 peo- forearc, refl ects diverse earthquake rupture clarifi es earthquake clustering in the central ple, destroyed the port of Kobe, and caused modes with variable recurrence. Stratigraphy Puget Lowland, but cannot resolve potential $100 billion in damage (Chang, 2010). -

By Arthur Grantz This Report Is Preliminary and Has Not Been

DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY STRIKE-SLIP FAULTS ITT ALASKA By Arthur Grantz OPEN-FILE REPORT This report is preliminary and has not been edited cr reviewed for conformity vich Geological Survey standards and nomenclature. CONTENTS Page Introduction- - - - - - -- 1 Structural environment of the strike-slip faults- h Description of strike- slip faults and selected linear features-- 10 Denali fault and Dcnali fault system -- 10 Farewell segment of the Denali fault " 1^ Hines Creek strand of the Denali fault - 16 McKinley strand of the Denali fault 17 Shakwak Valley segment of the Denali fault 20 Togiak-Tikchik fault-- 2U Holitna fault 25 Chilkat River fault zone-- - - - 26 Chatham Strait fault- 26 Castle Mountain fault 27 Iditarod-Nixon Fork fault - -- 28 And. ak- Thompson Creek fault- - - 30 Conjugate strike -slip faults in the Yukon delta region 30 Kaltag fault 31 Stevens Creek fault zone-- - ----- 33 Porcupine lineament-- ----- ------ -- _- - - 33 Yukon Flats discontinuity and fault--- - - --- 3^ Tintina fault zone and Tintina trench- - -- 35 Kobuk trench- - - 38 Fairweather fault-------- - -------- - -- 38 Peril Strait fault *K) Chichagof-Sitka fault and its likely southeastern extension, the Patter son Biy fault-- - ----- Ul Clarence Stra.it lincan 2nt- Age of faulting U2 Maximum apparent lateral separations- U6 Superposition of lateral slip upon pre-existing faults- ^9 Hypotheses involving the strike-slip faults 50 Relation to right-lateral slip along the Pacific Coast- - 51 Internal rotation of Alaska - 53 Bending -

Surface Rupture of the 14 Nov 2016 Kaikoura

The 14 Nov 2016 Mw 7.8 Kaikoura Earthquake: Surface rupture ... and much more Pilar Villamor on behalf of the Earthquake Geology Response Team (54): Adrian Benson, Alan Bischoff, Alex Hatem, Andrea Barrier, Andy Nicol, Anekant Wandres, Biljana Lukovic, Brendan Hall, Caleb Gasston, Callum Margetts, Cam Asher, Chris Grimshaw, Chris Madugo, Clark Fenton, Dan Hale, David Barrell, David Heron, Delia Strong, Dougal Townsend, Duncan Noble, Jamie Howarth, Jarg Pettinga, Jesse Kearse, Jack Williams, Joel Bensing, John Manousakis, Josh Borella, Joshu Mountjoy, Julie Rowland, Kate Clark, Kate Pedley, Katrina Sauer, Kelvin Berryman, Mark Hemphill-Haley, Mark Stirling, Marlene Villeneuve, Matt Cockroft, Narges Khajavi, Nick Griffiths, Philip Barnes, Pilar Villamor, Rachel Carne, Robert Langridge, Robert Zinke, Russ van Dissen, Sam McColl, Simon Cox, Steve Lawson, Tim Little, Tim Stahl, Ursula Cochran, Virgina Toy, William Ries, Zoe Juniper GNS Science 14 November Kaikoura Earthquake This talk - Background - Kaikoura Earthquake - Seismicity, ground motions - InSAR and GNSS - Preliminary rupture models - Surface Rupture - Tsunami, Landslides (if we have time..) Photo: Sally Dellow, GNS Science Surface rupture of the Papatea Fault displacing the coastal platform, road, railway and hill country. GNS Science Background • The 14 Nov event occurred in the region between the Hikurangi subduction system of the North Island and the oblique collisional regime of the South Island (Alpine Fault) GNS Science Background • The 14 Nov event ruptured several faults that expand into different tectonic domains: o The strike-slip Marlborough fault system consists of a series of right lateral strike-slip faults, some with reverse component, that link to the Alpine fault on the west and to the subduction margin fore-arc to the east. -

Surface Rupture Database for Seismic Hazard Assessment

RAPPORT Surface rupture database for Seismic Hazard Assessment 2015 Report of the Kick-Off Meeting of the “SURE Database” Working Group RT/PRP-DGE/2016-00022 Pôle radioprotection, environnement, déchets et crise Service de caractérisation des sites et des aléas naturels ABSTRACT The goal of the fault displacement hazard assessment is to describe and quantify the permanent displacement that can occur during an earthquake at the ground surface. One of the methods to do so is probabilistic (PFDHA: Probabilistic Fault Displacement Hazard Analysis) and is basically based on empirical approaches which allows predicting the possible displacement on the earthquake fault (« on-fault » displacement) and off this major fault on other fault segments (« off-fault » displacement). Predictive relationships (also called “regressions”) were published in the last 15 years (e.g. Youngs et al., 2003; Petersen et al., 2011; Takao et al., 2013) and they are based on data catalogs limited in case numbers and in magnitude ranges. Because there are practical applications of PFDHA in terms of engineering, there is concern in the geologists and engineers communities, for instance in the INQUA and the IAEA-ISSC groups, to improve the methodology. A first and critical step is to build up a community-sourced, worldwide, unified database of surface rupturing earthquakes to include a large number of earthquake cases in various seismotectonic contexts. This is the core task of the SURE (Surface Rupture Earthquake) Working Group which is growing with the support of INQUA and IAEA-ISSC. During the kick-off meeting held in Paris (October 2015) and sponsored by the Institut de Radioprotection et Sûreté Nucléaire (IRSN), earthquake geology experts from the USA, Europe (France, Italy, UK, Germany), Japan, New Zealand, South America (Argentina) formed this group and exchanged their experience in surface rupturing events during 3 days.