Transformations in the Okanagan Wine Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Red Wines – Steve Zins 11/12/2014 Final Rev 5.0 Contents

German Red Wines – Steve Zins 11/12/2014 Final Rev 5.0 Contents • Introduction • German Wine - fun facts • German Geography • Area Classification • Wine Production • Trends • Permitted Reds • Wine Classification • Wine Tasting • References Introduction • Our first visit to Germany was in 2000 to see our daughter who was attending college in Berlin. We rented a car and made a big loop from Frankfurt -Koblenz / Rhine - Black forest / Castles – Munich – Berlin- Frankfurt. • After college she took a job with Honeywell, moved to Germany, got married, and eventually had our first grandchild. • When we visit we always try to visit some new vineyards. • I was surprised how many good red wines were available. So with the help of friends and family we procured and carried this collection over. German Wine - fun facts • 90% of German reds are consumed in Germany. • Very few wine retailers in America have any German red wines. • Most of the largest red producers are still too small to export to USA. • You can pay $$$ for a fine French red or drink German reds for the entire year. • As vineyard owners die they split the vineyards between siblings. Some vineyards get down to 3 rows. Siblings take turns picking the center row year to year. • High quality German Riesling does not come in a blue bottle! German Geography • Germany is 138,000 sq mi or 357,000 sq km • Germany is approximately the size of Montana ( 146,000 sq mi ) • Germany is divided with respect to wine production into the following: • 13 Regions • 39 Districts • 167 Collective vineyard -

May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author' s Permission) p CLASS ACTS: CULINARY TOURISM IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR by Holly Jeannine Everett A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2005 St. John's Newfoundland ii Class Acts: Culinary Tourism in Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis, building on the conceptual framework outlined by folklorist Lucy Long, examines culinary tourism in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The data upon which the analysis rests was collected through participant observation as well as qualitative interviews and surveys. The first chapter consists of a brief overview of traditional foodways in Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as a summary of the current state of the tourism industry. As well, the methodology which underpins the study is presented. Chapter two examines the historical origins of culinary tourism and the development of the idea in the Canadian context. The chapter ends with a description of Newfoundland and Labrador's current culinary marketing campaign, "A Taste of Newfoundland and Labrador." With particular attention to folklore scholarship, the course of academic attention to foodways and tourism, both separately and in tandem, is documented in chapter three. The second part of the thesis consists of three case studies. Chapter four examines the uses of seal flipper pie in hegemonic discourse about the province and its culture. Fried foods, specifically fried fish, potatoes and cod tongues, provide the starting point for a discussion of changing attitudes toward food, health and the obligations of citizenry in chapter five. -

Viticulture Research and Outreach Addressing the Ohio Grape and Wine Industry Production Challenges

HCS Series Number 853 ANNUAL OGIC REPORT (1 July ’16 – 30 June ‘17) Viticulture Research and Outreach Addressing the Ohio Grape and Wine Industry Production Challenges Imed Dami, Professor & Viticulture State Specialist Diane Kinney, Research Assistant II VITICULTURE PROGRAM Department of Horticulture and Crop Science 1 Table of Contents Page Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………..………….3 2016 Weather………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……..5 Viticulture Research……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…… 10 Project #1: Trunk Renewal Methods for Vine Recovery After Winter Injury……………………………………… 11 Project #2: Evaluation of Performance and Cultural Practices of Promising Wine Grape Varieties….. 16 Viticulture Production…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….28 Commercial Expansion of Varieties New to Ohio………………………………………………………………………………….28 Viticulture Extension & Outreach……………………………………………………………………………………………41 OGEN and Fruit Maturity Updates………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 41 Ohio Grape & Wine Conference………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 42 Industry Field Day and Workshops………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 43 “Buckeye Appellation” Website………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 45 Industry Meetings………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 45 Professional Meetings…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 45 Student Training & Accomplishments…………………………………………………………………………………… 49 Honors & Awards………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 50 Appendix………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Genetic Structure and Domestication History of the Grape

Genetic structure and domestication history of the grape Sean Mylesa,b,c,d,1, Adam R. Boykob, Christopher L. Owense, Patrick J. Browna, Fabrizio Grassif, Mallikarjuna K. Aradhyag, Bernard Prinsg, Andy Reynoldsb, Jer-Ming Chiah, Doreen Wareh,i, Carlos D. Bustamanteb, and Edward S. Bucklera,i aInstitute for Genomic Diversity, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; bDepartment of Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305; cDepartment of Biology, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada B4P 2R6; dDepartment of Plant and Animal Sciences, Nova Scotia Agricultural College, Truro, NS, Canada B2N 5E3; eGrape Genetics Research Unit, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Cornell University, Geneva, NY 14456; fBotanical Garden, Department of Biology, University of Milan, 20133 Milan, Italy; gNational Clonal Germplasm Repository, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; hCold Spring Harbor Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724; and iRobert W. Holley Center for Agriculture and Health, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY14853 Edited* by Barbara A. Schaal, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, and approved December 9, 2010 (received for review July 1, 2010) The grape is one of the earliest domesticated fruit crops and, since sociations using linkage mapping. Because of the grape’s long antiquity, it has been widely cultivated and prized for its fruit and generation time (generally 3 y), however, establishing and wine. Here, we characterize genome-wide patterns of genetic maintaining linkage-mapping populations is time-consuming and variation in over 1,000 samples of the domesticated grape, Vitis expensive. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

2017 Avinyo Cava Reserva/Xarelo /Penedes, Spain Forest-Marie Brut

BUBBLES BEER THE SELECTED TO COMPLEMENT OUR CUISINE WINE BEVERAGE WINES ASK YOUR SERVER FOR SUGGESTIONS BUBBLY GL BTL NATURAL GL BTL 2017 avinyo cava reserva / xarelo / penedes, spain 17 68 NV desert nights pet nat / famoso / ravenna, italy 67 NV forest-marie brut rosé / pinot noir, pinot munier / france 116 2018 les lunes / chardonnay / redwood valley, usa 75 NV bortolotti prosecco / glera / piedmont, italy 68 2019 vinca minor old vine / chardonnay, sauv blanc / mendocino, usa 69 ROSÉ NV electric lightning pet nat rosé / longanese / ravenna, italy 17 68 2020 72 2017 pojer e sandri / rotberger / dolomiti, italy 58 donkey & goat isabel’s rosé / grenache / mendocino, usa 2017 t&r bailey mae / grenache, cinsault / walla walla valley, usa 17 68 2019 garalis roseus rosé / muscat of alexandria, limnio / lemnos, greece 62 2017 tre monti poche ore / sangiovese / emilia romagna, italy 64 2018 cosmic juice pet nat* / longanese / ravenna, italy 72 2018 electric sssupermoon, 1 ltr bottle* / longanese / ravenna, italy 82 WHITE 2020 las jaras glou glou* / zinfandel, carignane, more / california, usa 70 2019 brander mesa verde vineyard / sauv blanc / los olivos, usa 17 68 2019 macchiarola bizona* / primativo / lizzano, italy 72 2017 clos pegase / chardonnay / carneros, usa 18 72 2017 martha stoumen / nero d’avola / mendocino county, ca 96 2013 emanuel tres blanco / grenache, viognier / santa ynez, usa 78 2018 montesecondo / sangiovese / cebaia, italy 89 2017 kistler les noisetiers / chardonnay / sonoma coast, usa 125 2018 quintessa illumination / sauvignon -

Regulatory and Institutional Developments in the Ontario Wine and Grape Industry

International Journal of Wine Research Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article OrigiNAL RESEARCH Regulatory and institutional developments in the Ontario wine and grape industry Richard Carew1 Abstract: The Ontario wine industry has undergone major transformative changes over the last Wojciech J Florkowski2 two decades. These have corresponded to the implementation period of the Ontario Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) Act in 1999 and the launch of the Winery Strategic Plan, “Poised for 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Pacific Agri-Food Research Greatness,” in 2002. While the Ontario wine regions have gained significant recognition in Centre, Summerland, BC, Canada; the production of premium quality wines, the industry is still dominated by a few large wine 2Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of companies that produce the bulk of blended or “International Canadian Blends” (ICB), and Georgia, Griffin, GA, USA multiple small/mid-sized firms that produce principally VQA wines. This paper analyzes how winery regulations, industry changes, institutions, and innovation have impacted the domestic production, consumption, and international trade, of premium quality wines. The results of the For personal use only. study highlight the regional economic impact of the wine industry in the Niagara region, the success of small/mid-sized boutique wineries producing premium quality wines for the domestic market, and the physical challenges required to improve domestic VQA wine retail distribution and bolster the international trade of wine exports. Domestic success has been attributed to the combination of natural endowments, entrepreneurial talent, established quality standards, and the adoption of improved viticulture practices. -

Media Kit the Wines of British Columbia “Your Wines Are the Wines of Sensational!” British Columbia ~ Steven Spurrier

MEDIA KIT THE WINES OF BRITISH COLUMBIA “YOUR WINES ARE THE WINES OF SENSATIONAL!” BRITISH COLUMBIA ~ STEVEN SPURRIER British Columbia is a very special place for wine and, thanks to a handful of hard-working visionaries, our vibrant industry has been making a name for itself nationally and internationally for the past 25 years. “BC WINE OFTEN HAS In 1990, the Vintner’s Quality Alliance (VQA) standard was created to guarantee consumers they A RADICAL FRESHNESS were drinking wine made from 100% BC grown grapes. Today, BC VQA Wines dominate wine sales AND A REMARKABLE in British Columbia, and our wines are finding their way to more places than ever before, winning ABILITY TO DEFY over both critics and consumers internationally. THE CONVENTIONAL CATEGORIES OF TASTE.” The Wines of British Columbia truly are a reflection of the land where the grapes are grown and the exceptional people who craft them. We invite you to join us to savour all that makes the Wines of STUART PIGOTT British Columbia so special. ~ “WHAT I LOVE MOST ABOUT BC WINES IS THEY MIMIC THE PLACE, THEY MIMIC THE PURITY. YOU LOOK OUT AND FEEL THE AIR, TASTE THE WATER AND LOOK AT THE LAKE AND YOU CAN’T HELP BUT BE STRUCK BY A SENSE OF PURITY AND IT CARRIES OVER TO THE WINE. THEY HAVE PURITY AND A SENSE OF WEIGHTLESSNESS WHICH IS VERY ETHEREAL AND CAPTIVATING.” ~ KAREN MACNEIL DID YOU KNOW? • British Columbia’s Vintners Quality Alliance (BC VQA) designation celebrated 25 years of excellence in 2015. • BC’s Wine Industry has grown from just 17 grape wineries in 1990 to more than 275 today (as of January 2017). -

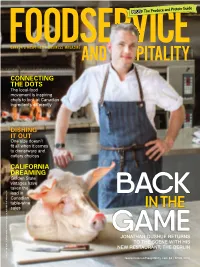

Connecting the Dots

CONNECTING THE DOTS The local-food movement is inspiring chefs to look at Canadian ingredients differently DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to dinnerware and cutlery choices CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden State vintages have taken the lead in Canadian table-wine sales JONATHAN GUSHUE RETURNS TO THE SCENE WITH HIS NEW RESTAURANT, THE BERLIN CANADIAN PUBLICATION MAIL PRODUCT SALES AGREEMENT #40063470 CANADIAN PUBLICATION foodserviceandhospitality.com $4 | APRIL 2016 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2016 CONTENTS 40 27 14 Features 11 FACE TIME Whether it’s eco-proteins 14 CONNECTING THE DOTS The 35 CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden or smart technology, the NRA Show local-food movement is inspiring State vintages have taken the lead aims to connect operators on a chefs to look at Canadian in Canadian table-wine sales host of industry issues ingredients differently By Danielle Schalk By Jackie Sloat-Spencer By Andrew Coppolino 37 DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit 22 BACK IN THE GAME After vanish - all when it comes to dinnerware and ing from the restaurant scene in cutlery choices By Denise Deveau 2012, Jonathan Gushue is back CUE] in the spotlight with his new c restaurant, The Berlin DEPARTMENTS By Andrew Coppolino 27 THE SUSTAINABILITY PARADIGM 2 FROM THE EDITOR While the day-to-day business of 5 FYI running a sustainable food operation 12 FROM THE DESK is challenging, it is becoming the new OF ROBERT CARTER normal By Cinda Chavich 40 CHEF’S CORNER: Neil McCue, Whitehall, Calgary PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY [NEIL M OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE FOODSERVICEANDHOSPITALITY.COM FOODSERVICE AND HOSPITALITY APRIL 2016 1 FROM THE EDITOR For daily news and announcements: @foodservicemag on Twitter and Foodservice and Hospitality on Facebook. -

Wine Tourism Insight

Wine Tourism Product BUILDING TOURISM WITH INSIGHT WINE October 2009 This profile summarizes information on the British Columbia wine tourism sector. Wine tourism, for the purpose of this profile, includes the tasting, consumption or purchase of wine, often at or near the source, such as wineries. Wine tourism also includes organized education, travel and celebration (i.e. festivals) around the appreciation of, tasting of, and purchase of wine. Information provided here includes an overview of BC’s wine tourism sector, a demographic and travel profile of Canadian and American travellers who participated in wine tourism activities while on pleasure trips, detailed information on motivated wine travellers to BC, and other outdoor and cultural activities participated in by wine travellers. Also included are overall wine tourism trends as well as a review of Canadian and US wine consumption trends, motivation factors of wine tourists, and an overview of the BC wine industry from the supply side. Research in this report has been compiled from several sources, including the 2006 Travel Activities and Motivations Study (TAMS), online reports (i.e. www.winebusiness.com), Statistics Canada, Wine Australia, (US) Wine Market Council, Winemakers Federation of Australia, Tourism New South Wales (Australia) and the BC Wine Institute. For the purpose of this tourism product profile, when describing results from TAMS data, participating wine tourism travellers are defined as those who have taken at least one overnight trip in 2004/05 where they participated in at least one of three wine tourism activities (1) Cooking/Wine tasting course; (2) Winery day visits; or (3) Wine tasting school. -

President's Report

FISCAL 2018: 2nd PRESIDENT'S REPORT QUARTER REVIEW In what is clearly a vindication of Celebrate the Wines of British Columbia's growing potential as British Columbia a wine industry, both of collective reviews the work of the success and viability, Andrew Peller BC Wine Institute Ltd.'s $95 million-dollar purchase of during each quarter of three prestigious BC wineries, with a the fiscal year. subsequent $25 million investment over the next five years, can only be This 2nd quarter described as bullish for our industry as review covers activities a whole. that occurred during Miles Prodan July, August and These three wineries own 250 acres of BC vineyards, produce September 2017. 125,000 cases of wine, and recorded sales of $24.5 million in 2016. A publicly-run company headquartered in Ontario, Peller In this issue Estate Ltd. is welcoming these wineries into its existing portfolio President's Report of premium BC VQA wines that includes Sandhill Wines, Red Rooster Winery, and Conviction Wines (formerly Calona Message from BCWI Vineyard's BC VQA Artist Series Brand). The proprietors and Marketing Director company are no strangers to BC and remains one of the most Message from BCWI experienced producers of BC VQA Wine. Media Relations Manager It is inevitable that some will cry foul over a perceived takeover Market Dashboard of iconic 'estate' wineries considered among the forbearers of our BC VQA Wine industry by an organization that by its history Marketing Events and successes is simply categorized as 'large'. Realistically, Report however, this is a designation used only by the BC Wine Media Report Institute to ensure good governance and fair representation on Social Media Report its Board and bears no relevance to the commitment to our industry. -

Wedding Food & Beverage Wedding Entrées

wedding food & beverage 2021-22 wedding entrées Garlic Rosemary Chicken Whole chicken cut into 9-piece segments and slow roasted in a rosemary BBQ sauce. Braised Pork Shoulder Pork shoulder braised for 14-hours in our signature spice rub, Old Yale Sasquatch Stout, and house made BBQ sauce. Beef Tenderloin Tenderloin medallions pan seared and finished in the oven with a red wine reduction. Baked Salmon Filet Salmon baked with your choice of pineapple citrus salsa or creamy leek sauce and toasted almonds. Carved Honey Ham Baked honey glazed ham with a sweet grainy mustard. Blackened Chicken Grilled chicken breasts with your choice of Cajun creole or creamy spinach Florentine. Prime Rib Slow roasted prime rib with a red wine and herb au jus. Eggplant and Falafel Stuffed Peppers Roasted red peppers stuffed with eggplant, falafel, sautéed vegetables, and a tomato herb sauce. Black Bean and Chickpea Croquettes Black beans, corn, chickpeas, vegetables, and herbs hand pressed lightly breaded and then fried served with roasted tomato salsa. Ratatouille Layers of roasted vegetables slow roasted in tomato sauce. wedding food & beverage 2021-22 salads Seven-Leaf Mixed Heritage Greens with Assorted Dressings Caesar Salad with Fresh Asiago & Roasted Garlic Dressing Homestyle Potato Salad Greek Pasta Salad Salad Caprese Roasted Vegetable Salad with Balsamic Reduction Quinoa & Mixed Seven Bean Salad in an Herb Vinaigrette Fresh Dinner Rolls (included) starches Rainbow Potato with Herbes De Provence Olive Oil Roasted Rosemary Garlic Rainbow Potatoes Baked