Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sports and Physical Education in China

Sport and Physical Education in China Sport and Physical Education in China contains a unique mix of material written by both native Chinese and Western scholars. Contributors have been carefully selected for their knowledge and worldwide reputation within the field, to provide the reader with a clear and broad understanding of sport and PE from the historical and contemporary perspectives which are specific to China. Topics covered include: ancient and modern history; structure, administration and finance; physical education in schools and colleges; sport for all; elite sport; sports science & medicine; and gender issues. Each chapter has a summary and a set of inspiring discussion topics. Students taking comparative sport and PE, history of sport and PE, and politics of sport courses will find this book an essential addition to their library. James Riordan is Professor and Head of the Department of Linguistic and International Studies at the University of Surrey. Robin Jones is a Lecturer in the Department of PE, Sports Science and Recreation Management, Loughborough University. Other titles available from E & FN Spon include: Sport and Physical Education in Germany ISCPES Book Series Edited by Ken Hardman and Roland Naul Ethics and Sport Mike McNamee and Jim Parry Politics, Policy and Practice in Physical Education Dawn Penney and John Evans Sociology of Leisure A reader Chas Critcher, Peter Bramham and Alan Tomlinson Sport and International Politics Edited by Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century Edited by James Riordan and Robin Jones Understanding Sport An introduction to the sociological and cultural analysis of sport John Home, Gary Whannel and Alan Tomlinson Journals: Journal of Sports Sciences Edited by Professor Roger Bartlett Leisure Studies The Journal of the Leisure Studies Association Edited by Dr Mike Stabler For more information about these and other titles published by E& FN Spon, please contact: The Marketing Department, E & FN Spon, 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 205 The 2nd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2018) Study on the Feasibility of Setting up Archery in Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University Li Li Department of Physical Education Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University Shaanxi, China Abstract—This article uses the literature review method and the survey and interview method. The author analyzes the II. RESEARCH METHODS feasibility of setting up the course of traditional Chinese China is one of the earliest countries in the world to archery in colleges and universities. Finally, it has made the invent bow and arrow. In the long course of history, there are conclusion. And in his opinion, "archery" can effectively 120 works related to "shooting art". These historical sites are promote the harmonious development of college students' body rich in content. The historical values and cultural values are and mind. In the university, the archery field, equipment, extremely high. And they are precious national and cultural teachers, safety and other things can meet the relevant requirements. Therefore, it can also build a reasonable, heritage. Since ancient times, shooting art focuses on the scientific and diversified evaluation system of archery course. combination of self-cultivation and inner perception. The so- This is not only the rejuvenation of traditional competitive called "Qing Qiantang" and "Li Qiguan" are the fusion of the sports, but also the inheritance of the historical humanistic "hearts". The famous ideologist and founder Li Yanxue has spirit. the works of "Book of Rites", "Justice", "Record", "The road of love" and so on. -

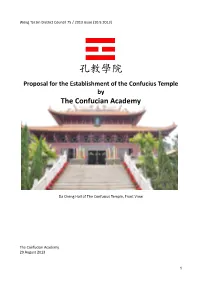

Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy

Wong Tai Sin District Council 75 / 2013 issue (10.9.2013) 孔教學院 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by The Confucian Academy Da Cheng Hall of The Confucius Temple, Front View The Confucian Academy 29 August 2013 1 Content 1. Objectives ……………………………………………………….………………..……….…………… P.3 2. An Introduction to Confucianism …………………………………..…………….………… P.3 3. Confucius, the Confucius Temple and the Confucian Academy ………….….… P.4 4. Ideology of the Confucius Temple ………………………………..…………………….…… P.5 5. Social Values in the Construction of the Confucius Temple …………..… P.7 – P.9 6. Religious Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………..……….… P.9 – P.12 7. Cultural Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………………..……P.12- P.18 8. Site Selection ………………………………………………………………………………………… P.18 9. Gross Floor Area (GFA) of the Confucius Temple …………………….………………P.18 10. Facilities …………………………………………………………………….……………… P.18 – P.20 11. Construction, Management and Operation ……………….………………. P.20– P.21 12. Design Considerations ………………………………………………………………. P.21 – P.24 13. District Consultation Forums .…………………………………..…………….…………… P.24 14. Alignment with Land Use Development …….. …………………………….………… P.24 15. The Budget ……………………………………………………………………………………………P.24 ※ Wong Tai Sin District and the Confucius Temple …………………………….….... P.25 Document Submission……………………………………………………………………………….. P.26 Appendix 1. Volume Drawing (I) of the Confucius Temple ………………..……….P.27 Appendix 2. Volume Drawing (II) of the Confucius Temple …………….………….P.28 Appendix 3. Design Drawings of the Confucius Temple ……………………P.29 – P.36 2 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy 1. Objectives This document serves as a proposal for the construction of a Confucius Temple in Hong Kong by the Confucian Academy, an overview of the design and architecture of the aforementioned Temple, as well as a way of soliciting the advice and support from the Wong Tai Sin District Council and its District Councillors. -

The Olympic Games and Ritual Archery 14.1 08

UNIVERSITY OF PELOPONNESE FACULTY OF HUMAN MOVEMENT AND QUALITY OF LIFE SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SPORTS ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT MASTER’S THESIS “OLYMPIC STUDIES, OLYMPIC EDUCATION, ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT OF OLYMPIC EVENTS” The Olympic Games and Ritual Archery: A Comparative Study of Sport between Ancient Greece and Early China (—200 BC) Nianliang Pang Supervisor : Professor Dr. Susan Brownell Dr. Werner Petermandl Dr. Zinon Papakonstantinou Sparta, Dec., 2013 i Abstract This research conducts a comparison between the Olympic Games in ancient Greece and ritual archery in early China before 200 BC, illustrating the similarities and differences between the two institutionalized cultural activities in terms of their trans-cultural comparison in regard to their origin, development, competitors, administration, process and function. Cross cultural comparison is a research method to comprehend heterogeneous culture through systematic comparisons of cultural factors across as wide domain. The ritual archery in early China and the Olympic Games in ancient Greece were both long-lived, institutionalized physical competitive activities integrating competition, rituals and music with communication in the ancient period. To compare the two programs can make us better understand the isolated civilizations in that period. In examining the cultural factors from the two programs, I find that both were originally connected with religion and legendary heroes in myths and experienced a process of secularization; both were closely intertwined with politics in antiquity, connected physical competitions with moral education, bore significant educational functions and played an important role in respective society. The administrators of the two cultural programs had reputable social rank and were professional at managing programs with systematic administrative knowledge and procedures. -

Ancient and Modern Methods of Arrow-Release

GN 498 B78 M88 I CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All books are subject to recall after two weeks. Olin/Kroch Library ^jUifi&E. DUE Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 924029871 823 The attention of the readfer is earnestly called to' the conclud- ing paragraphs on pages 55^56, with the hope that observations on the points therein ipentioned may be made and forwarded to the author, for which, full credit will be given in a future publi- cation on the subject/ Salem, Mass.^U. S. A. Brit ANCIENT AND MODEI# METHODS ARROW-RELEASE EDWlpD S. MORSE. Director SeaSodu Academy of Science. [From the Bulletin oi?*he Essex Institute, Vol. XVII. Oct--Deo. 1885.] '. , .5., i>' riC . „ '' '*\ fJC ,*/ •' 8^ /• % ,<\ '''//liiiunil^ ANCIENT AND MODERlfMETHODS OF p w ARROW-RELEASE. BY EDWARD S. MORSE. When I began collecting data illustrating the various methods of releasing the/arrow from the bow as prac- ticed by different races, I was animated only by the idlest curiosity. It soon became evident, however, that some importance might^Jfesfch to preserving the methods of handling a -Wamm which is rapidly being displaced in all parts ofiBffworld by the musket and rifle. While tribes stjJHKirvive who rely entirely on this most ancient of weajapns, using, even to the present day, stone-tipped arroj|^ there are other tribes using the rifle where the bow ^11 survives. There are, however, entire tribes and natiolfcvho have but recently, or within late historic its timeHsrabandoned the bow and arrow, survival being seenlpnly as a plaything for children. -

Zen Bow, Zen Arrow • • • the Life and Teachings of Awa Kenzo, the Archery Master from Zen in the Art of Archery • • • John Stevens

“An interesting and enlightening study by John Stevens.”—The Japan Times ABOUT THE BOOK Here are the inspirational life and teachings of Awa Kenzo (1880–1939), the Zen and kyudo (archery) master who gained worldwide renown after the publication of Eugen Herrigel’s cult classic Zen in the Art of Archery in 1953. Kenzo lived and taught at a pivotal time in Japan’s history, when martial arts were practiced primarily for self-cultivation, and his wise and penetrating instructions for practice (and life)—including aphorisms, poetry, instructional lists, and calligraphy—are infused with the spirit of Zen. Kenzo uses the metaphor of the bow and arrow to challenge the practitioner to look deeply into his or her own true nature. JOHN STEVENS is Professor of Buddhist Studies and Aikido instructor at Tohoku Fukushi University in Sendai, Japan. He is the author or translator of over twenty books on Buddhism, Zen, Aikido, and Asian culture.He has practiced and taught Aikido all over the world. Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. Master Zen Archer Awa Kenzo (1880–1939). Photo taken in 1932 or 1933. Courtesy of the Abe Family. Zen Bow, Zen Arrow • • • The Life and Teachings of Awa Kenzo, the Archery Master from Zen in the Art of Archery • • • John Stevens SHAMBHALA • Boston & London • 2012 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. HORTICULTURAL HALL 300 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2007 by John Stevens Cover design by Jonathan Sainsbury Cover art: “Shigong and the Bow” by Sengai. -

Starting Off with Manchu Archery | Fe Doro - Manchu Archery

Starting off with Manchu archery | Fe Doro - Manchu archery http://www.manchuarchery.org/content/starting-manchu-archery I often get asked questions about starting with Manchu archery, so here's an introduction. Defining features of Manchu archery The defining feature of this archery tradition is its focus on shooting large and comparatively heavy arrows with wooden shafts that were ideal for large game hunting or armor penetration. The bow used to shoot these projectiles is a large composite bow with string bridges and long rigid ears. Another defining feature is the use of a cylindrical thumb ring, instead of the more common teardrop shaped rings that were used in large parts of Asia and the Islamic world and even parts of Europe. These cylindrical rings could be worn all the time. Much of what passes as "Manchu archery" today leans heavily on tales of the successes of the Qing military, for marketing purposes, while at the same time failing to accurately reproduce it's defining features: Shooting large wooden arrows from a large long-eared composite bow -or a substitute with similar mechanics- with a cylindrical thumb ring. This is the point where I would like the aspiring Manchu archer to stop and think about what he or she is getting himself into, because literally everything is more difficult for Manchu archers! Let me explain below. - - - EQUIPMENT - - - The bow True Manchu bows have very long ears with a forward bend, from 26 to 33 cm from knee to ear and 18-23 cm from nock to inside of the string bridge. -

Chinese Thumb Rings: from Battlefield to Jewelry Box

Volume 6 No. 4 ISSN # 1538-0807 Winter 2007 Adornment The Magazine of Jewelry & Related Arts™ Carved jade archer’s rings, one with jade case, 9th-0th c. The two green rings are jadeite, the others nephrite. (Courtesy Eldred’s Auction Gallery) Qing dynasty ivory rings, one with silver liner. (top row University of Missouri Anthropology Museum; bottom row Special Collections/Musselman Library, Gettysburg College) Jade rings, top row Burmese jadeite, bottom row nephrite. (author’s collection). 4 Chinese Thumb Rings: From Battlefield to Jewelry Box By Eric J. Hoffman It is not often that an implement of warfare evolves into an item of jewelry. But that is precisely what happened with Chinese archer’s rings. From ancient times, archery in Asia was well developed for warfare, hunting, and sport. Archery implements have been unearthed in Chinese tombs going back at least 4000 years. The Mongolian warriors who conquered China in 1271 to establish the Yuan dynasty owed much of their success to their skill in shooting arrows from horseback. Their implements, techniques, and tactics allowed them to shoot their targets from galloping horses and then twist around in the saddle for a parting backward shot after passing. The Manchu clan that conquered China 400 years later to establish China’s final dynasty, the Qing, was equally skilled with bow and arrow. Their prowess with archery—again, especially from horseback— allowed a relatively small band of Manchus to conquer all of China and rule it for over 250 years. A number of technological developments contributed to the success of archery in northeastern China. -

A Comprehensive Handbook of Chinese Archaic Jades

A Comprehensive Handbook of Chinese Archaic Jades Authentication, Appreciation & Appraisal By Mitchell Chen 1 A Comprehensive Handbook of Chinese Archaic Jades : Authentication, Appreciation & Appraisal, Copyright © 2015 by Mitchell Chen. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, please contact [email protected]. 2 This book is dedicated to My wife Sulan Chen For her warmest support which makes this book possible 3 Foreword The Chinese are a people that have shown a great appreciation on jade. The jade history in China can be traced back as long as eight thousand years. Jade collection, therefore, is not just a hobby. Today, jade authentication, jade appreciation, and jade appraisal have become an interdisciplinary subject in many universities in Taiwan. Professor Mitchell Chen had five years of teaching experiences at the Center of General Education, JinWen University of Science and Technology. The courses he lectured include Antique Jade Authentication and Appraisal, Oriental Arts and Craftsmanship. Professor Chen was not only a teacher, but also a collector. In every class he lectured, he used his own collection as the teaching material. In addition to obtaining the knowledge, all the students in his class benefited a lot by examining real objects. Now Professor Chen is sharing his expertise on the Chinese archaic jade with all the readers in the world by publishing this book. I believe all the jade lovers will enjoy reading this book and obtain the knowledge of Chinese archaic jade authentication, appreciation, and appraisal. -

Depictions of Archery in Sassanian Silver Plates and Their Relationship

Revista de Artes Marciales Asiáticas Volumen 13(2), 82-113 ~ Julio-Diciembre 2018 DOI: 10.18002/rama.v13i2.5370 RAMA I.S.S.N. 2174-0747 http://revpubli.unileon.es/ojs/index.php/artesmarciales Depictions of archery in Sassanian silver plates and their relationship to warfare Kaveh FARROKH1 * , Manouchehr Moshtagh KHORASANI2 , & Bede DWYER3 1 University of British Columbia (Canada) 2 Razmafzar Organization (Germany) 3 Razmafzar Organization (Australia) Recepción: 19/02/2018; Aceptación: 29/08/2018; Publicación: 10/09/2018. ORIGINAL PAPER Abstract This article provides an examination of archery techniques, such as drawing techniques of the bowstring, the method of grasping the bow grip and placing the arrow, and their relationship to warfare as depicted on 22 Sassanian and early post-Sassanian silver plates. These plates provide useful information on Sassanian archery equipment and techniques. These plates can be categorized into the following categories: (a) foot archery, (b) horse archery, c) dromedary archery and (d) elephant archery. All plates examined in this study depicting these categories are in a hunting milieu. The largest proportion of plates pertain to horse archery which in turn can be classified into four combat subsets: forward-facing horse archery, the backward-firing Parthian shot, horse archery with stirrups, and horse archery while appearing to ride backwards. Keywords: Martial arts; Persian martial arts; historical martial arts; Sassanian bow; archery; composite bow. Representaciones de tiro con arco en platos Representações -

The Silk Road , Vol. 8

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 8 2010 Contents From the Editor’s Desktop ................................................................... 3 Images from Ancient Iran: Selected Treasures from the National Museum in Tehran. A Photographic Essay ............................................................... 4 Ancient Uighur Mausolea Discovered in Mongolia, by Ayudai Ochir, Tserendorj Odbaatar, Batsuuri Ankhbayar and Lhagwasüren Erdenebold .......................................................................................... 16 The Hydraulic Systems in Turfan (Xinjiang), by Arnaud Bertrand ................................................................................. 27 New Evidence about Composite Bows and Their Arrows in Inner Asia, by Michaela R. Reisinger .......................................................................... 42 An Experiment in Studying the Felt Carpet from Noyon uul by the Method of Polypolarization, by V. E. Kulikov, E. Iu. Mednikova, Iu. I. Elikhina and Sergei S. Miniaev .................... 63 The Old Curiosity Shop in Khotan, by Daniel C. Waugh and Ursula Sims-Williams ................................................. 69 Nomads and Settlement: New Perspectives in the Archaeology of Mongolia, by Daniel C. Waugh ................................................................................ 97 (continued) “The Bridge between Eastern and Western Cultures” Book notices (except as noted, by Daniel C. Waugh) The University of Bonn’s Contributions to Asian Archaeology -

An Aspect of the Abilities of Steppe Horse Archers in Eurasian Warfare (525 Bce – 1350 Ce)

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2020 SYNCHRONY: AN ASPECT OF THE ABILITIES OF STEPPE HORSE ARCHERS IN EURASIAN WARFARE (525 BCE – 1350 CE) Chris Hanson University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Military History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hanson, Chris, "SYNCHRONY: AN ASPECT OF THE ABILITIES OF STEPPE HORSE ARCHERS IN EURASIAN WARFARE (525 BCE – 1350 CE)" (2020). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11563. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11563 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYNCHRONY: AN ASPECT OF THE ABILITIES OF STEPPE HORSE ARCHERS IN EURASIAN WARFARE (525 BCE – 1350 CE) By Christopher D. Hanson B.A. Anthropology with and eMphasis in Archaeology, The University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2012 B.A. Central and Southwest Asia Studies, The University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2012 Thesis presented in partial fulfillMent of the requireMents for the degree of Master of Arts in General Anthropology, Central and Southwest Asian Studies The University of Montana Missoula, MT Official Graduation Date May 2020 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr.