Ritual Comes Before Shooting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sports and Physical Education in China

Sport and Physical Education in China Sport and Physical Education in China contains a unique mix of material written by both native Chinese and Western scholars. Contributors have been carefully selected for their knowledge and worldwide reputation within the field, to provide the reader with a clear and broad understanding of sport and PE from the historical and contemporary perspectives which are specific to China. Topics covered include: ancient and modern history; structure, administration and finance; physical education in schools and colleges; sport for all; elite sport; sports science & medicine; and gender issues. Each chapter has a summary and a set of inspiring discussion topics. Students taking comparative sport and PE, history of sport and PE, and politics of sport courses will find this book an essential addition to their library. James Riordan is Professor and Head of the Department of Linguistic and International Studies at the University of Surrey. Robin Jones is a Lecturer in the Department of PE, Sports Science and Recreation Management, Loughborough University. Other titles available from E & FN Spon include: Sport and Physical Education in Germany ISCPES Book Series Edited by Ken Hardman and Roland Naul Ethics and Sport Mike McNamee and Jim Parry Politics, Policy and Practice in Physical Education Dawn Penney and John Evans Sociology of Leisure A reader Chas Critcher, Peter Bramham and Alan Tomlinson Sport and International Politics Edited by Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century Edited by James Riordan and Robin Jones Understanding Sport An introduction to the sociological and cultural analysis of sport John Home, Gary Whannel and Alan Tomlinson Journals: Journal of Sports Sciences Edited by Professor Roger Bartlett Leisure Studies The Journal of the Leisure Studies Association Edited by Dr Mike Stabler For more information about these and other titles published by E& FN Spon, please contact: The Marketing Department, E & FN Spon, 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 205 The 2nd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2018) Enlightenment of Confucian Music Education on Improving College Students' Humanities Accomplishment* Qin Zeng Mengni Fan College of Fine Arts and Film College of Fine Arts and Film Chengdu University Chengdu University Chengdu, China 610106 Chengdu, China 610106 Abstract—This paper has studied the thought of Confucian charisma. And it has made guidance and inspiration on the music culture of Confucius, Mencius and Xunzi. Also, it has cultivation and improvement of the humanistic explored the connotation of Confucian music culture. And accomplishment of college students. contemporary college students would study and understand the essence of Confucian music culture. The contemporary college students would improve their own humanities, and II. CONFUCIUS THOUGHT OF MUSIC EDUCATION AND cultivate both ability and political integrity. ITS ENLIGHTENMENT ON THE QUALITY-ORIENTED EDUCATION OF COLLEGE STUDENTS Keywords—Confucianism; the culture of music education; Confucius was the founder of Confucianism. He humanity accomplishment; enlightenment proposed the education idea of "six arts", namely, rites, music, shooting, driving, books and numbers. In the later I. INTRODUCTION years, he revised the six classics, namely "The Book of Confucianism is the traditional Chinese culture Songs", "The Book of History", "The Rites", "Classic of represented by Confucius, Mencius and Xunzi in the Spring Music" and "The Spring and Autumn Annals". And he used and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period. the six classics as the textbook. He required the students to Confucian music culture is an important part of learn the text and make self-discipline with the rites". -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 205 The 2nd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2018) Study on the Feasibility of Setting up Archery in Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University Li Li Department of Physical Education Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University Shaanxi, China Abstract—This article uses the literature review method and the survey and interview method. The author analyzes the II. RESEARCH METHODS feasibility of setting up the course of traditional Chinese China is one of the earliest countries in the world to archery in colleges and universities. Finally, it has made the invent bow and arrow. In the long course of history, there are conclusion. And in his opinion, "archery" can effectively 120 works related to "shooting art". These historical sites are promote the harmonious development of college students' body rich in content. The historical values and cultural values are and mind. In the university, the archery field, equipment, extremely high. And they are precious national and cultural teachers, safety and other things can meet the relevant requirements. Therefore, it can also build a reasonable, heritage. Since ancient times, shooting art focuses on the scientific and diversified evaluation system of archery course. combination of self-cultivation and inner perception. The so- This is not only the rejuvenation of traditional competitive called "Qing Qiantang" and "Li Qiguan" are the fusion of the sports, but also the inheritance of the historical humanistic "hearts". The famous ideologist and founder Li Yanxue has spirit. the works of "Book of Rites", "Justice", "Record", "The road of love" and so on. -

![[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1753/re-viewing-the-chinese-landscape-imaging-the-body-in-visible-in-shanshuihua-1061753.webp)

[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫

[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫 Lim Chye Hong 林彩鳳 A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chinese Studies School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales Australia abstract This thesis, titled '[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫,' examines shanshuihua as a 'theoretical object' through the intervention of the present. In doing so, the study uses the body as an emblem for going beyond the surface appearance of a shanshuihua. This new strategy for interpreting shanshuihua proposes a 'Chinese' way of situating bodily consciousness. Thus, this study is not about shanshuihua in a general sense. Instead, it focuses on the emergence and codification of shanshuihua in the tenth and eleventh centuries with particular emphasis on the cultural construction of landscape via the agency of the body. On one level the thesis is a comprehensive study of the ideas of the body in shanshuihua, and on another it is a review of shanshuihua through situating bodily consciousness. The approach is not an abstract search for meaning but, rather, is empirically anchored within a heuristic and phenomenological framework. This framework utilises primary and secondary sources on art history and theory, sinology, medical and intellectual history, ii Chinese philosophy, phenomenology, human geography, cultural studies, and selected landscape texts. This study argues that shanshuihua needs to be understood and read not just as an image but also as a creative transformative process that is inevitably bound up with the body. -

Post 91 the Six Arts of Ancient China

1000 Days in China – Post 91 May 2, 2021 The Six Arts (liù yì – 六艺) of Ancient China In Ancient China during the Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BC), students of Nobility were required to master the “Six Arts (liù yì – 六艺 – in Chinese)”. The “Six Arts” included rituals(礼), music(乐), archery(射), charioteering(御), writing(书) and mathematics(数). The six arts emphasized comprehensive development in all subject areas, and attempted to educate students to be well-rounded. In researching these “Six Arts”, it foreshadowed some of the values during the Renaissance Age in Europe that would occur about 2,000 years later. These Six Arts also formed the foundations of Chinese Thinking and Philosophy. RITUALS(礼) Ritual is an extraordinarily important cornerstone in Chinese culture. Without rituals, the 5,000-year-old country would never exist. In ancient China, there were officers in charge of rituals for every aspect of life, like marriage, funerals, and sacrifice. Chinese people started to live with a sense of ritual thousands of years ago and nothing can remove it from Chinese culture. MUSIC(乐) Music was not just a melody or a pastime for entertainment in ancient China. It was a symbol of great manners and a well-educated person. To learn music, one should have high aesthetic standards. Confucius himself studied from three different people to learn courtesy, music and how to play music. A famous saying of Confucius on music education is: “To educate somebody, you should start from poems, emphasize ceremonies and finish with music.” In other words, one cannot expect to become educated without learning music. -

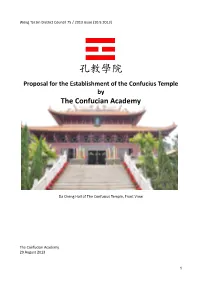

Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy

Wong Tai Sin District Council 75 / 2013 issue (10.9.2013) 孔教學院 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by The Confucian Academy Da Cheng Hall of The Confucius Temple, Front View The Confucian Academy 29 August 2013 1 Content 1. Objectives ……………………………………………………….………………..……….…………… P.3 2. An Introduction to Confucianism …………………………………..…………….………… P.3 3. Confucius, the Confucius Temple and the Confucian Academy ………….….… P.4 4. Ideology of the Confucius Temple ………………………………..…………………….…… P.5 5. Social Values in the Construction of the Confucius Temple …………..… P.7 – P.9 6. Religious Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………..……….… P.9 – P.12 7. Cultural Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………………..……P.12- P.18 8. Site Selection ………………………………………………………………………………………… P.18 9. Gross Floor Area (GFA) of the Confucius Temple …………………….………………P.18 10. Facilities …………………………………………………………………….……………… P.18 – P.20 11. Construction, Management and Operation ……………….………………. P.20– P.21 12. Design Considerations ………………………………………………………………. P.21 – P.24 13. District Consultation Forums .…………………………………..…………….…………… P.24 14. Alignment with Land Use Development …….. …………………………….………… P.24 15. The Budget ……………………………………………………………………………………………P.24 ※ Wong Tai Sin District and the Confucius Temple …………………………….….... P.25 Document Submission……………………………………………………………………………….. P.26 Appendix 1. Volume Drawing (I) of the Confucius Temple ………………..……….P.27 Appendix 2. Volume Drawing (II) of the Confucius Temple …………….………….P.28 Appendix 3. Design Drawings of the Confucius Temple ……………………P.29 – P.36 2 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy 1. Objectives This document serves as a proposal for the construction of a Confucius Temple in Hong Kong by the Confucian Academy, an overview of the design and architecture of the aforementioned Temple, as well as a way of soliciting the advice and support from the Wong Tai Sin District Council and its District Councillors. -

The Olympic Games and Ritual Archery 14.1 08

UNIVERSITY OF PELOPONNESE FACULTY OF HUMAN MOVEMENT AND QUALITY OF LIFE SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SPORTS ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT MASTER’S THESIS “OLYMPIC STUDIES, OLYMPIC EDUCATION, ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT OF OLYMPIC EVENTS” The Olympic Games and Ritual Archery: A Comparative Study of Sport between Ancient Greece and Early China (—200 BC) Nianliang Pang Supervisor : Professor Dr. Susan Brownell Dr. Werner Petermandl Dr. Zinon Papakonstantinou Sparta, Dec., 2013 i Abstract This research conducts a comparison between the Olympic Games in ancient Greece and ritual archery in early China before 200 BC, illustrating the similarities and differences between the two institutionalized cultural activities in terms of their trans-cultural comparison in regard to their origin, development, competitors, administration, process and function. Cross cultural comparison is a research method to comprehend heterogeneous culture through systematic comparisons of cultural factors across as wide domain. The ritual archery in early China and the Olympic Games in ancient Greece were both long-lived, institutionalized physical competitive activities integrating competition, rituals and music with communication in the ancient period. To compare the two programs can make us better understand the isolated civilizations in that period. In examining the cultural factors from the two programs, I find that both were originally connected with religion and legendary heroes in myths and experienced a process of secularization; both were closely intertwined with politics in antiquity, connected physical competitions with moral education, bore significant educational functions and played an important role in respective society. The administrators of the two cultural programs had reputable social rank and were professional at managing programs with systematic administrative knowledge and procedures. -

Childhood in Premodern China by John W. Dardess Please Share Your

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this Book Chapter benefits you. Childhood in Premodern China by John W. Dardess 1991 This is the published version of the Book Chapter, made available with the permission of the publisher. The original published version can be found at the link below. Dardess, John W. “Childhood in Premodern China.” In Joseph M. Hawes and N. Ray Hiner, eds., Children in Historical and Comparative Perspective (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991), pp. 71-94. Published version: http://www.abc-clio.com/product. aspx?isbn=9780313257605 Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml KU ScholarWorks is a service provided by the KU Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication & Copyright. 5 CHILDHOOD IN PREMODERN CHINA John Dardess The history of childhood in China is a subject wholly untouched until recently. The potential body of source materials for such a study—or indeed series of studies—is large to the point of unmanageability, and scattered over a variety of written genres, both native and foreign. I shall open up the topic by introducing some of the principal kinds of written works that deal with childhood in whole or in part. I have in mind the reader who may not be familiar with Chinese history and society, but who may have a vague sense that a Chinese childhood will have been lived in obedience to some unfamiliar order of rules and expectations. Western-language sources are considered first, followed by a review of the topic from within the resources that Chinese civilization has itself produced over the past millennium or so. -

Ancient and Modern Methods of Arrow-Release

GN 498 B78 M88 I CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All books are subject to recall after two weeks. Olin/Kroch Library ^jUifi&E. DUE Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 924029871 823 The attention of the readfer is earnestly called to' the conclud- ing paragraphs on pages 55^56, with the hope that observations on the points therein ipentioned may be made and forwarded to the author, for which, full credit will be given in a future publi- cation on the subject/ Salem, Mass.^U. S. A. Brit ANCIENT AND MODEI# METHODS ARROW-RELEASE EDWlpD S. MORSE. Director SeaSodu Academy of Science. [From the Bulletin oi?*he Essex Institute, Vol. XVII. Oct--Deo. 1885.] '. , .5., i>' riC . „ '' '*\ fJC ,*/ •' 8^ /• % ,<\ '''//liiiunil^ ANCIENT AND MODERlfMETHODS OF p w ARROW-RELEASE. BY EDWARD S. MORSE. When I began collecting data illustrating the various methods of releasing the/arrow from the bow as prac- ticed by different races, I was animated only by the idlest curiosity. It soon became evident, however, that some importance might^Jfesfch to preserving the methods of handling a -Wamm which is rapidly being displaced in all parts ofiBffworld by the musket and rifle. While tribes stjJHKirvive who rely entirely on this most ancient of weajapns, using, even to the present day, stone-tipped arroj|^ there are other tribes using the rifle where the bow ^11 survives. There are, however, entire tribes and natiolfcvho have but recently, or within late historic its timeHsrabandoned the bow and arrow, survival being seenlpnly as a plaything for children. -

Zen Bow, Zen Arrow • • • the Life and Teachings of Awa Kenzo, the Archery Master from Zen in the Art of Archery • • • John Stevens

“An interesting and enlightening study by John Stevens.”—The Japan Times ABOUT THE BOOK Here are the inspirational life and teachings of Awa Kenzo (1880–1939), the Zen and kyudo (archery) master who gained worldwide renown after the publication of Eugen Herrigel’s cult classic Zen in the Art of Archery in 1953. Kenzo lived and taught at a pivotal time in Japan’s history, when martial arts were practiced primarily for self-cultivation, and his wise and penetrating instructions for practice (and life)—including aphorisms, poetry, instructional lists, and calligraphy—are infused with the spirit of Zen. Kenzo uses the metaphor of the bow and arrow to challenge the practitioner to look deeply into his or her own true nature. JOHN STEVENS is Professor of Buddhist Studies and Aikido instructor at Tohoku Fukushi University in Sendai, Japan. He is the author or translator of over twenty books on Buddhism, Zen, Aikido, and Asian culture.He has practiced and taught Aikido all over the world. Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. Master Zen Archer Awa Kenzo (1880–1939). Photo taken in 1932 or 1933. Courtesy of the Abe Family. Zen Bow, Zen Arrow • • • The Life and Teachings of Awa Kenzo, the Archery Master from Zen in the Art of Archery • • • John Stevens SHAMBHALA • Boston & London • 2012 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. HORTICULTURAL HALL 300 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2007 by John Stevens Cover design by Jonathan Sainsbury Cover art: “Shigong and the Bow” by Sengai. -

Starting Off with Manchu Archery | Fe Doro - Manchu Archery

Starting off with Manchu archery | Fe Doro - Manchu archery http://www.manchuarchery.org/content/starting-manchu-archery I often get asked questions about starting with Manchu archery, so here's an introduction. Defining features of Manchu archery The defining feature of this archery tradition is its focus on shooting large and comparatively heavy arrows with wooden shafts that were ideal for large game hunting or armor penetration. The bow used to shoot these projectiles is a large composite bow with string bridges and long rigid ears. Another defining feature is the use of a cylindrical thumb ring, instead of the more common teardrop shaped rings that were used in large parts of Asia and the Islamic world and even parts of Europe. These cylindrical rings could be worn all the time. Much of what passes as "Manchu archery" today leans heavily on tales of the successes of the Qing military, for marketing purposes, while at the same time failing to accurately reproduce it's defining features: Shooting large wooden arrows from a large long-eared composite bow -or a substitute with similar mechanics- with a cylindrical thumb ring. This is the point where I would like the aspiring Manchu archer to stop and think about what he or she is getting himself into, because literally everything is more difficult for Manchu archers! Let me explain below. - - - EQUIPMENT - - - The bow True Manchu bows have very long ears with a forward bend, from 26 to 33 cm from knee to ear and 18-23 cm from nock to inside of the string bridge. -

Liberal Arts Education in the Chinese Context

CHAPTER 2 Liberal Arts Education in the Chinese Context Numerous books and articles have been dedicated to the study of Chinese higher education, but liberal arts education is still a little-researched subject. This is due, in part, to the effort and emphasis placed on specialized or profes- sional education since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 (Gan 2006). Since the early 1990s the reemergence of liberal arts education in China has drawn the attention of Chinese universities, and the Chinese gov- ernment has realized that this is an important part of “comprehensive quality education” (i.e., a well-rounded education). This chapter provides the aca- demic and historical context for understanding the current state of liberal arts education in Chinese universities. It begins with a focus on liberal arts educa- tion in its historical context and variations in the way the liberal arts have been defined. It then introduces the development of Chinese higher education over the past three decades, following China’s institution of its Open Door policy and its undertaking of reform in its social, economic, political, and educational sectors. Special emphasis is placed on the last fifteen years, when liberal arts education emerged. This chapter also reviews the history of Chinese education and the development of liberal arts education. The last section of the chap- ter examines how the Chinese Ministry of Education’s policy initiatives have impacted liberal arts education reform at the university level in China. Confucian Tradition The emergence of liberal arts education in China in the last two decades is a new phenomenon (M.L.