Pearl from the Dragon Mouth: Evocation of Scene and Feeling In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras YEN-WEN CHENG University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation CHENG, YEN-WEN, "Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 98. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras Abstract After obtaining sovereignty, a new emperor of China often gathers the imperial collections of previous dynasties and uses them as evidence of the legitimacy of the new regime. Some emperors go further, commissioning the compilation projects of bibliographies of books and catalogues of artistic works in their imperial collections not only as inventories but also for proclaiming their imperial power. The imperial collections of art symbolize political and cultural predominance, present contemporary attitudes toward art and connoisseurship, and reflect emperors’ personal taste for art. The attempt of this research project is to explore the practice of art cataloguing during two of the most important reign periods in imperial China: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (r. 1101-1125) and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (r. 1736-1795). Through examining the format and content of the selected painting, calligraphy, and bronze catalogues compiled by both emperors, features of each catalogue reveal the development of cataloguing imperial artistic collections. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 09:41:18AM Via Free Access 102 M

Asian Medicine 7 (2012) 101–127 brill.com/asme Palpable Access to the Divine: Daoist Medieval Massage, Visualisation and Internal Sensation1 Michael Stanley-Baker Abstract This paper examines convergent discourses of cure, health and transcendence in fourth century Daoist scriptures. The therapeutic massages, inner awareness and visualisation practices described here are from a collection of revelations which became the founding documents for Shangqing (Upper Clarity) Daoism, one of the most influential sects of its time. Although formal theories organised these practices so that salvation superseded curing, in practice they were used together. This blending was achieved through a series of textual features and synæsthesic practices intended to address existential and bodily crises simultaneously. This paper shows how therapeutic inter- ests were fundamental to soteriology, and how salvation informed therapy, thus drawing atten- tion to the entanglements of religion and medicine in early medieval China. Keywords Massage, synæsthesia, visualisation, Daoism, body gods, soteriology The primary sources for this paper are the scriptures of the Shangqing 上清 (Upper Clarity), an early Daoist school which rose to prominence as the fam- ily religion of the imperial family. The soteriological goal was to join an elite class of divine being in the Shangqing heaven, the Perfected (zhen 真), who were superior to Transcendents (xianren 仙). Their teachings emerged at a watershed point in the development of Daoism, the indigenous religion of 1 I am grateful for the insightful criticisms and comments on draughts of this paper from Robert Campany, Jennifer Cash, Charles Chase, Terry Kleeman, Vivienne Lo, Johnathan Pettit, Pierce Salguero, and Nathan Sivin. -

Downloaded 4.0 License

86 Chapter 3 Chapter 3 Eloquent Stones Of the critical discourses that this book has examined, one feature is that works of art are readily compared to natural forms of beauty: bird song, a gush- ing river or reflections in water are such examples. Underlying such rhetorical devices is an ideal of art as non-art, namely that the work of art should appear so artless that it seems to have been made by nature in its spontaneous process of creation. Nature serves as the archetype (das Vorbild) of art. At the same time, the Song Dynasty also saw refined objects – such as flowers, tea or rocks – increasingly aestheticised, collected, classified, described, ranked and com- moditised. Works of connoisseurship on art or natural objects prospered alike. The hundred-some pu 譜 or lu 錄 works listed in the literature catalogue in the History of the Song (“Yiwenzhi” in Songshi 宋史 · 藝文志) are evenly divided between those on manmade and those on natural objects.1 Through such dis- cursive transformation, ‘natural beauty’ as a cultural construct curiously be- came the afterimage (das Nachbild) of art.2 In other words, when nature appears as the ideal of art, at the same time it discovers itself to be reshaped according to the image of art. As a case study of Song nature aesthetics, this chapter explores the multiple dimensions of meaning invested in Su Shi’s connoisseur discourse on rocks. Su Shi professed to be a rock lover. Throughout his life, he collected inkstones, garden rocks and simple pebbles. We are told, for instance, that a pair of rocks, called Qiuchi 仇池, accompanied him through his exiles to remote Huizhou and Hainan, even though most of his family members were left behind. -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/97g9d23n Author Mewhinney, Matthew Stanhope Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki By Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alan Tansman, Chair Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Daniel C. O’Neill Professor Anne-Lise François Summer 2018 © 2018 Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney All Rights Reserved Abstract The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki by Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Tansman, Chair This dissertation examines the transformation of lyric thinking in Japanese literati (bunjin) culture from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. I examine four poet- painters associated with the Japanese literati tradition in the Edo (1603-1867) and Meiji (1867- 1912) periods: Yosa Buson (1716-83), Ema Saikō (1787-1861), Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) and Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916). Each artist fashions a lyric subjectivity constituted by the kinds of blending found in literati painting and poetry. I argue that each artist’s thoughts and feelings emerge in the tensions generated in the process of blending forms, genres, and the ideas (aesthetic, philosophical, social, cultural, and historical) that they carry with them. -

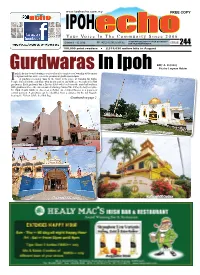

Your Voice in the Community Since 2006

www.ipohecho.com.my FREE COPY IPOH Your Voiceechoecho In The Community Since 2006 October 1 - 15, 2016 PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – ISSUE ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR 244 100,000 print readers 2,315,636 online hits in August By A. Jeyaraj Pics by Luqman Hakim Gurdwaraspoh Echo has been featuring a series of articles on places of worship of the major In Ipoh religions and this issue covers the prominent gurdwaras in Ipoh. I A gurdwara meaning 'door to the Guru' is the place of worship for Sikhs. People from all faiths, and those who do not profess any faith, are welcomed in Sikh gurdwaras. Each gurdwara has a Darbar Sahib which refers to the main hall within a Sikh gurdwara where the current and everlasting Guru of the Sikhs, the holy scripture Sri Guru Granth Sahib, is placed on a Takhat (an elevated throne) in a prominent central position. A gurdwara can be identified from a distance by the tall flagpole bearing the Nishan Sahib, the Sikh flag. Continued on page 2 Gurdwara Sahib Greentown Central Sikh Temple Gurdwara Sahib Bercham Gurdwara Sahib Buntong 2 October 1 - 15, 2016 IPOH ECHO Your Voice In The Community Gurdwaras: a focal point for all Sikh religious, cultural and community activities erak, where most of the early Sikhs settled, and wherever there were Sikhs, a gurdwara was sure to follow, has the most number of gurdwaras with 42 out of a Gurdwara Sahib Greentown, Jalan Hospital Ptotal of 119 in Malaysia. The Gurdwara Sahib Greentown is situated on a hilltop and commands a majestic view of the surroundings. -

Taiwan After the Election

ANALYSIS CHINA TAIWAN AFTER THE ELECTION Introduction ABOUT by François Godement The Chinese have long been obsessed with strategic culture, power balances and geopolitical shifts. Academic institutions, think tanks, journals Taiwan is important as an unresolved issue. It is also the and web-based debate are growing in number and European Union’s fifth-largest trade partner in Asia and a quality and give China’s foreign policy breadth and source of major investment abroad. For years, Europe has depth. had a very simple two-sided declaratory policy – no use of China Analysis, which is published in both French force and no independence – that has been likened to a “one and English, introduces European audiences to China” policy. Under that mantle, relations have expanded, these debates inside China’s expert and think-tank including a visa-free policy of greeting Taiwanese tourists world and helps the European policy community and businessmen. For these reasons, Europe’s approach understand how China’s leadership thinks appears now stationary. During his first term in the past about domestic and foreign policy issues. While freedom of expression and information remain five years, President Ma Ying-jeou has greatly stabilised restricted in China’s media, these published political cross-strait relations, helped by China’s decision to sources and debates provide an important way of be patient. Taiwan has collected the economic profits and understanding emerging trends within China. also opened itself to visitors from the mainland for the first time since 1949. Each issue of China Analysis focuses on a specific theme and draws mainly on Chinese mainland sources. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 205 The 2nd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2018) Enlightenment of Confucian Music Education on Improving College Students' Humanities Accomplishment* Qin Zeng Mengni Fan College of Fine Arts and Film College of Fine Arts and Film Chengdu University Chengdu University Chengdu, China 610106 Chengdu, China 610106 Abstract—This paper has studied the thought of Confucian charisma. And it has made guidance and inspiration on the music culture of Confucius, Mencius and Xunzi. Also, it has cultivation and improvement of the humanistic explored the connotation of Confucian music culture. And accomplishment of college students. contemporary college students would study and understand the essence of Confucian music culture. The contemporary college students would improve their own humanities, and II. CONFUCIUS THOUGHT OF MUSIC EDUCATION AND cultivate both ability and political integrity. ITS ENLIGHTENMENT ON THE QUALITY-ORIENTED EDUCATION OF COLLEGE STUDENTS Keywords—Confucianism; the culture of music education; Confucius was the founder of Confucianism. He humanity accomplishment; enlightenment proposed the education idea of "six arts", namely, rites, music, shooting, driving, books and numbers. In the later I. INTRODUCTION years, he revised the six classics, namely "The Book of Confucianism is the traditional Chinese culture Songs", "The Book of History", "The Rites", "Classic of represented by Confucius, Mencius and Xunzi in the Spring Music" and "The Spring and Autumn Annals". And he used and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period. the six classics as the textbook. He required the students to Confucian music culture is an important part of learn the text and make self-discipline with the rites". -

An Explanation of Gexing

Front. Lit. Stud. China 2010, 4(3): 442–461 DOI 10.1007/s11702-010-0107-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE XUE Tianwei, WANG Quan An Explanation of Gexing © Higher Education Press and Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Gexing 歌行 is a historical and robust prosodic style that flourished (not originated) in the Tang dynasty. Since ancient times, the understanding of the prosody of gexing has remained in debate, which focuses on the relationship between gexing and yuefu 乐府 (collection of ballad songs of the music bureau). The points-of-view held by all sides can be summarized as a “grand gexing” perspective (defining gexing in a broad sense) and four major “small gexing” perspectives (defining gexing in a narrow sense). The former is namely what Hu Yinglin 胡应麟 from Ming dynasty said, “gexing is a general term for seven-character ancient poems.” The first “small gexing” perspective distinguishes gexing from guti yuefu 古体乐府 (tradition yuefu); the second distinguishes it from xinti yuefu 新体乐府 (new yuefu poems with non-conventional themes); the third takes “the lyric title” as the requisite condition of gexing; and the fourth perspective adopts the criterion of “metricality” in distinguishing gexing from ancient poems. The “grand gexing” perspective is the only one that is able to reveal the core prosodic features of gexing and give specification to the intension and extension of gexing as a prosodic style. Keywords gexing, prosody, grand gexing, seven-character ancient poems Received January 25, 2010 XUE Tianwei ( ) College of Humanities, Xinjiang Normal University, Urumuqi 830054, China E-mail: [email protected] WANG Quan International School, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing 100029, China E-mail: [email protected] An Explanation of Gexing 443 The “Grand Gexing” Perspective and “Small Gexing” Perspective Gexing, namely the seven-character (both unified seven-character lines and mixed lines containing seven character ones) gexing, occupies an equal position with rhythm poems in Tang dynasty and even after that in the poetic world. -

Chinese Poetry and Its Institutions

Chinese Poetry and Its Institutions Pauline Yu (余寶琳) University of California, Los Angeles In a recent interview the American poet Jorie Graham offers an illurninating account of what, in her view, poe t:ry白 , 缸ld how it is produced. Graham is, even for seasoned critics, something of a cballenge to read, someone whose work takes on 1 訂ge issues with startling imagerγand nonlinear leaps of 出 ough t. For her, poe甘y uses “language in a special way-not to report or record experience, but to create experience in a m缸mer that would be 世1- possible without the medium of words. ‘In poe訂y you bave to feel deeply something inchoate, something which is coming up 企om a place 出 at you don't even know the register of,' sbe says."l Her description of how she writes is, unsurprisingly, poetic and, indeed, syn 自由 etic: “ I need to be in an app訂 ently empty frame of mind, without the noise of thinking so h訂 d. You 訂e 甘ying to hear the music of yo叮 own t趾nking in poe甘 y , and ifyou have silence around you, it helps. I have never known where I'm going to st訂t. Often there's a music, or sound, or an image that 伊aws . It invites the senses to do a kind ofwork you don't quite bave ins甘uctions for. Then ques tions attach themselves to a current that feels, perhaps, more ancient. A good poem is always a reaction, a moment of acute surprise that occurred in the soul of the speaker. You want to go somewhere you haven't been before. -

China During the Tang-Song Interregnum, 878–978

China during the Tang-Song Interregnum, 878–978 This book challenges the long-established structure of Chinese history around dynasties, adopting a more “organic” approach which emphasises cultural and economic trends that transcend arbitrary dynastic boundaries. It argues that with the collapse of the Tang court and northern control over the holistic empire in the last decades of the ninth century, the now-autonomous kingdoms that filled the political vacuum in the south responded with a burst of innovative energy that helped set the stage for the economic and cultural transformations of the following Song dynasty. Moreover, it argues that these transformations and this economic and cultural innovation deeply affected the subsequent model of holistic empire which continues right up to the present and that therefore the interregnum century of division left a critically important legacy. Hugh R. Clark is Professor Emeritus of History and East Asian Studies at Ursinus College, Pennsylvania Asian States and Empires Edited by Peter Lorge, Vanderbilt University For a full list of available titles please visit: https://www.routledge.com/Asian- States-and-Empires/book-series/SE900. The importance of Asia will continue to grow in the twenty-first century, but remarkably little is available in English on the history of the polities that constitute this critical area. Most current work on Asia is hindered by the extremely limited state of knowledge of the Asian past in general, and the history of Asian states and empires in particular. Asian States and Empires is a book series that will provide detailed accounts of the history of states and empires across Asia from earliest times until the present.