"Dragon" Boat Racing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

Sports and Physical Education in China

Sport and Physical Education in China Sport and Physical Education in China contains a unique mix of material written by both native Chinese and Western scholars. Contributors have been carefully selected for their knowledge and worldwide reputation within the field, to provide the reader with a clear and broad understanding of sport and PE from the historical and contemporary perspectives which are specific to China. Topics covered include: ancient and modern history; structure, administration and finance; physical education in schools and colleges; sport for all; elite sport; sports science & medicine; and gender issues. Each chapter has a summary and a set of inspiring discussion topics. Students taking comparative sport and PE, history of sport and PE, and politics of sport courses will find this book an essential addition to their library. James Riordan is Professor and Head of the Department of Linguistic and International Studies at the University of Surrey. Robin Jones is a Lecturer in the Department of PE, Sports Science and Recreation Management, Loughborough University. Other titles available from E & FN Spon include: Sport and Physical Education in Germany ISCPES Book Series Edited by Ken Hardman and Roland Naul Ethics and Sport Mike McNamee and Jim Parry Politics, Policy and Practice in Physical Education Dawn Penney and John Evans Sociology of Leisure A reader Chas Critcher, Peter Bramham and Alan Tomlinson Sport and International Politics Edited by Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century Edited by James Riordan and Robin Jones Understanding Sport An introduction to the sociological and cultural analysis of sport John Home, Gary Whannel and Alan Tomlinson Journals: Journal of Sports Sciences Edited by Professor Roger Bartlett Leisure Studies The Journal of the Leisure Studies Association Edited by Dr Mike Stabler For more information about these and other titles published by E& FN Spon, please contact: The Marketing Department, E & FN Spon, 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 205 The 2nd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2018) Study on the Feasibility of Setting up Archery in Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University Li Li Department of Physical Education Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University Shaanxi, China Abstract—This article uses the literature review method and the survey and interview method. The author analyzes the II. RESEARCH METHODS feasibility of setting up the course of traditional Chinese China is one of the earliest countries in the world to archery in colleges and universities. Finally, it has made the invent bow and arrow. In the long course of history, there are conclusion. And in his opinion, "archery" can effectively 120 works related to "shooting art". These historical sites are promote the harmonious development of college students' body rich in content. The historical values and cultural values are and mind. In the university, the archery field, equipment, extremely high. And they are precious national and cultural teachers, safety and other things can meet the relevant requirements. Therefore, it can also build a reasonable, heritage. Since ancient times, shooting art focuses on the scientific and diversified evaluation system of archery course. combination of self-cultivation and inner perception. The so- This is not only the rejuvenation of traditional competitive called "Qing Qiantang" and "Li Qiguan" are the fusion of the sports, but also the inheritance of the historical humanistic "hearts". The famous ideologist and founder Li Yanxue has spirit. the works of "Book of Rites", "Justice", "Record", "The road of love" and so on. -

Nachruf Eberhard Wolfram

216 Monumenta Germaniae Historica und übersetzt von Ernst T r e rn p . ( Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatim editi 64.) Verlag Hahnsehe Buchhandlung, Hannover. Benzo von Alba, Ad Heinricum imperatorem Libri VII. Hg. von Hans S e y f f er t. ( Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separa tim editi 65.) Verlag Hahnsehe Buchhandlung, Hannover. Opus Caroli regis contra synodum (Libri Carolini). Hg. von Ann Nachrufe Fr e e man. (Concilia 2, Supplementum.) Verlag Hahnsehe Buchhandlung, Hannover. Die Konzilsordines des Früh- und Hochmittelalters. Hg. von Herbert Wolfram Eberhard S c h n e i d e r . (Ordines de celebrando concilio.) Verlag Hahnsehe 17.3.1909-15.8.1989 Buchhandlung, Hannover. Die Urkunden Ludwigs II. Hg. von Hans Konrad W a n n e r . (Die Es gibt selbst unter den größten Gelehrten nur ganz wenige, deren Urkunden der Karolinger 4.) Verlag Monumenta Germaniae Historica, wissenschaftliches Werk bei aller Vielfalt einen in sich geschlossenen Kosmos gebildet, gleichzeitig aber Anregungen nach allen Seiten verströmt München. Die Briefe des Petrus Damiani. Teil4: Briefe 151-180. Register. Hg. von hat. Zu diesen Gelehrten gehörte das korrespondierende Mitglied der Baye Kurt R e i n d e I . (Die Briefe der deutschen Kaiserzeit 4,4.) Verlag rischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Professor Emeritus der University Monumenta Germaniae Historica, München. of California Wolfram Eberhard, der am 15. August 1989 nach langer Der Memorial- und Liturgiecodex von San Salvatore/Santa Giulia in Krankheit in seinem Heim in Oakland, Calif., verstorben ist. Er war, durch Brescia. Hg. von Kar! S c h m i d unter Mitwirkung von Arnold An g e - die schweren Umstände seiner Zeit, aber auch durch sein Verantwortungs n e n d t , Dieter G e u e n i c h , Jean V e z i n u. -

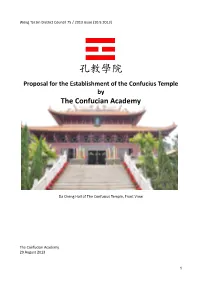

Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy

Wong Tai Sin District Council 75 / 2013 issue (10.9.2013) 孔教學院 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by The Confucian Academy Da Cheng Hall of The Confucius Temple, Front View The Confucian Academy 29 August 2013 1 Content 1. Objectives ……………………………………………………….………………..……….…………… P.3 2. An Introduction to Confucianism …………………………………..…………….………… P.3 3. Confucius, the Confucius Temple and the Confucian Academy ………….….… P.4 4. Ideology of the Confucius Temple ………………………………..…………………….…… P.5 5. Social Values in the Construction of the Confucius Temple …………..… P.7 – P.9 6. Religious Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………..……….… P.9 – P.12 7. Cultural Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………………..……P.12- P.18 8. Site Selection ………………………………………………………………………………………… P.18 9. Gross Floor Area (GFA) of the Confucius Temple …………………….………………P.18 10. Facilities …………………………………………………………………….……………… P.18 – P.20 11. Construction, Management and Operation ……………….………………. P.20– P.21 12. Design Considerations ………………………………………………………………. P.21 – P.24 13. District Consultation Forums .…………………………………..…………….…………… P.24 14. Alignment with Land Use Development …….. …………………………….………… P.24 15. The Budget ……………………………………………………………………………………………P.24 ※ Wong Tai Sin District and the Confucius Temple …………………………….….... P.25 Document Submission……………………………………………………………………………….. P.26 Appendix 1. Volume Drawing (I) of the Confucius Temple ………………..……….P.27 Appendix 2. Volume Drawing (II) of the Confucius Temple …………….………….P.28 Appendix 3. Design Drawings of the Confucius Temple ……………………P.29 – P.36 2 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy 1. Objectives This document serves as a proposal for the construction of a Confucius Temple in Hong Kong by the Confucian Academy, an overview of the design and architecture of the aforementioned Temple, as well as a way of soliciting the advice and support from the Wong Tai Sin District Council and its District Councillors. -

The Olympic Games and Ritual Archery 14.1 08

UNIVERSITY OF PELOPONNESE FACULTY OF HUMAN MOVEMENT AND QUALITY OF LIFE SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SPORTS ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT MASTER’S THESIS “OLYMPIC STUDIES, OLYMPIC EDUCATION, ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT OF OLYMPIC EVENTS” The Olympic Games and Ritual Archery: A Comparative Study of Sport between Ancient Greece and Early China (—200 BC) Nianliang Pang Supervisor : Professor Dr. Susan Brownell Dr. Werner Petermandl Dr. Zinon Papakonstantinou Sparta, Dec., 2013 i Abstract This research conducts a comparison between the Olympic Games in ancient Greece and ritual archery in early China before 200 BC, illustrating the similarities and differences between the two institutionalized cultural activities in terms of their trans-cultural comparison in regard to their origin, development, competitors, administration, process and function. Cross cultural comparison is a research method to comprehend heterogeneous culture through systematic comparisons of cultural factors across as wide domain. The ritual archery in early China and the Olympic Games in ancient Greece were both long-lived, institutionalized physical competitive activities integrating competition, rituals and music with communication in the ancient period. To compare the two programs can make us better understand the isolated civilizations in that period. In examining the cultural factors from the two programs, I find that both were originally connected with religion and legendary heroes in myths and experienced a process of secularization; both were closely intertwined with politics in antiquity, connected physical competitions with moral education, bore significant educational functions and played an important role in respective society. The administrators of the two cultural programs had reputable social rank and were professional at managing programs with systematic administrative knowledge and procedures. -

A Tibeti Műveltség Kézikönyve

Helmut Hoffmann A tibeti mûveltség kézikönyve Terebess Kiadó, Budapest, 2001 írta Helmut Hoffman, valamint Stanley Frye, Thubten J. Norbu és Yang Ho-chin programigazgató: Denis Sinor A mû eredeti címe: Tibet. A Handbook A fordítás alapjául szolgáló kiadás: Indiana University Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. Bloomington, Indiana. 2. vál- tozatlan kiadás 1986 (1. kiadás 1975). fordította, a bibliográfiát kiegészítette, a fõszöveg fényanyagában helyesbítéseket eszközölt, jegyzeteket írt és a mutatót összeállí- totta Csatlós Péter Helmut Hoffman: A tibeti mûveltség kézikönyve Ezt a könyvet Õszentségének a XIV. dalai lámának, Tendzin Gyacónak ajánljuk, szerény hozzájárulásként ama hatalmas feladathoz, hogy a tibeti civilizációval és vallással kapcsolatos tudást és tiszteletet nyugaton életben tarthassuk. Lektorálta: Kara György Elõszó A kézikönyv célja, hogy bemutassa a Tibet múltjával és jelené- vel kapcsolatos legfontosabb ma használatos tényanyagot és bibliográfiai adatokat. Segédanyagnak készült az amerikai felsõ- oktatás részére. Azok, akik – maguk nem szakemberként – megpróbáltak tibeti adatokat felhasználni belsõ-, kelet- és dél-ázsiai kurzu- saikban, tisztában vannak azokkal a nehézségekkel, amelyeket a megbízható és hozzáférhetõ információk hiánya okozott. Az igazat megvallva azonban el kell ismernünk, hogy Tibetrõl és lakóiról szép számmal akadnak általános, s néha felületes munkák. Tudományos cikkekben sincs hiány; sokukat idegen nyelven írták és olyan szakmai folyóiratokban jelentek meg, amelyek csak azok számára hozzáférhetõk, akik elég szerencsések ahhoz, hogy egy nagyobb és a témára szakosodott könyvtár közelében dolgozhatnak. Így ezek az írásbeli anyagok csak a szakemberek számára elérhetõk, és pont ez az egyik ok, amiért úgy gondoltuk, hogy egy olyan általános segédkönyv, mint a A tibeti mûveltség kézikönyve sok olyan tanár számára hasznos lenne, akik a témá- hoz máskülönben nem túl szorosan kapcsolódó kurzusokat tar- tanak. -

Western Sinology and Field Journals

Handbook of Reference Works in Traditional Chinese Studies (R. Eno, 2011) 9. WESTERN SINOLOGY AND FIELD JOURNALS This section of has two parts. The first outlines some aspects of the history of sinology in the West relevant to the contemporary shape of the field. The second part surveys some of the leading and secondary sinological journals, with emphasis on the role they have played historically. I. An outline of sinological development in the West The history of sinology in the West is over 400 years old. No substantial survey will be attempted here; that can wait until publication of The Lives of the Great Sinologists, a blockbuster for sure.1 At present, with Chinese studies widely dispersed in hundreds of teaching institutions, the lines of the scholarly traditions that once marked sharply divergent approaches are not as easy to discern as they were thirty or forty years ago, but they still have important influences on the agendas of the field, and they should be understood in broad outline. One survey approach is offered by the general introduction to Zurndorfer’s guide; its emphasis is primarily on the development of modern Japanese and Chinese scholarly traditions, and it is well worth reading. This brief summary has somewhat different emphases. A. Sinology in Europe The French school Until the beginning of the eighteenth century, Western views of China were principally derived from information provided by occasional travelers and by missionaries, particularly the Jesuits, whose close ties with the Ming and Ch’ing courts are engagingly portrayed by Jonathan Spence in his popular portraits, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci and Emperor of China. -

Ancient and Modern Methods of Arrow-Release

GN 498 B78 M88 I CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All books are subject to recall after two weeks. Olin/Kroch Library ^jUifi&E. DUE Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 924029871 823 The attention of the readfer is earnestly called to' the conclud- ing paragraphs on pages 55^56, with the hope that observations on the points therein ipentioned may be made and forwarded to the author, for which, full credit will be given in a future publi- cation on the subject/ Salem, Mass.^U. S. A. Brit ANCIENT AND MODEI# METHODS ARROW-RELEASE EDWlpD S. MORSE. Director SeaSodu Academy of Science. [From the Bulletin oi?*he Essex Institute, Vol. XVII. Oct--Deo. 1885.] '. , .5., i>' riC . „ '' '*\ fJC ,*/ •' 8^ /• % ,<\ '''//liiiunil^ ANCIENT AND MODERlfMETHODS OF p w ARROW-RELEASE. BY EDWARD S. MORSE. When I began collecting data illustrating the various methods of releasing the/arrow from the bow as prac- ticed by different races, I was animated only by the idlest curiosity. It soon became evident, however, that some importance might^Jfesfch to preserving the methods of handling a -Wamm which is rapidly being displaced in all parts ofiBffworld by the musket and rifle. While tribes stjJHKirvive who rely entirely on this most ancient of weajapns, using, even to the present day, stone-tipped arroj|^ there are other tribes using the rifle where the bow ^11 survives. There are, however, entire tribes and natiolfcvho have but recently, or within late historic its timeHsrabandoned the bow and arrow, survival being seenlpnly as a plaything for children. -

Wolfram Eberhard, 1909-1989

OBITUARY In Memoriam: Wolfram Eberhard, 1909-1989 A l v i n P. C o h e n University of Massachusetts, Amherst Wolfram Eberhard, Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University of California at Berkeley, was one of those rare scholars of Western, Cen tral, and Eastern Asian societies and cultures whose interests and abilities were so broad that he can justifiably be described as a genuine “ renais sance man ” of Asian studies. As a teacher and scholar, he directly or indirectly influenced the careers and lives of a generation of students and scholars in many parts of the world. Even after his retirement, he continued to actively teach and publish, as well as to inspire a new generation of students. The course of Professor Eberhard’s life and career reads almost like an adventure tale.1 He was born on March 1 7 ,1909,in Potsdam, Germany, into a family of astrophysicists and astronomers on both the paternal and maternal sides of his family. The family influence was to bear fruit in Eberhard’s doctoral dissertation on the astronomy and astrology of the Han Dynasty, and in several studies, coauthored with his uncle Rolf Muller, on the astronomy of the Han and Three Kingdom periods. These works were reprinted as volume 4 of EberharcTs col lected essays, Sternkunde und Weltbild im alien China (1970a). Eber hard was educated at the Victoria Gymnasium in Potsdam where he studied Latin, Greek, French, and two years of English. He had no other English instruction until 1948, when he arrived in the United States and was expected to start teaching in English within a few weeks. -

Zen Bow, Zen Arrow • • • the Life and Teachings of Awa Kenzo, the Archery Master from Zen in the Art of Archery • • • John Stevens

“An interesting and enlightening study by John Stevens.”—The Japan Times ABOUT THE BOOK Here are the inspirational life and teachings of Awa Kenzo (1880–1939), the Zen and kyudo (archery) master who gained worldwide renown after the publication of Eugen Herrigel’s cult classic Zen in the Art of Archery in 1953. Kenzo lived and taught at a pivotal time in Japan’s history, when martial arts were practiced primarily for self-cultivation, and his wise and penetrating instructions for practice (and life)—including aphorisms, poetry, instructional lists, and calligraphy—are infused with the spirit of Zen. Kenzo uses the metaphor of the bow and arrow to challenge the practitioner to look deeply into his or her own true nature. JOHN STEVENS is Professor of Buddhist Studies and Aikido instructor at Tohoku Fukushi University in Sendai, Japan. He is the author or translator of over twenty books on Buddhism, Zen, Aikido, and Asian culture.He has practiced and taught Aikido all over the world. Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. Master Zen Archer Awa Kenzo (1880–1939). Photo taken in 1932 or 1933. Courtesy of the Abe Family. Zen Bow, Zen Arrow • • • The Life and Teachings of Awa Kenzo, the Archery Master from Zen in the Art of Archery • • • John Stevens SHAMBHALA • Boston & London • 2012 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. HORTICULTURAL HALL 300 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2007 by John Stevens Cover design by Jonathan Sainsbury Cover art: “Shigong and the Bow” by Sengai. -

A History of China 1 a History of China

A History of China 1 A History of China The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of China, by Wolfram Eberhard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: A History of China Author: Wolfram Eberhard Release Date: February 28, 2004 [EBook #11367] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF CHINA *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Gene Smethers and PG Distributed Proofreaders [Transcriber's Note: The following text contains numerous non-English words containing diacritical marks not contained in the ASCII character set. Characters accented by those marks, and the corresponding text representations are as follows (where x represents the character being accented). All such symbols in this text above the character being accented: breve (u-shaped symbol): [)x] caron (v-shaped symbol): [vx] macron (straight line): [=x] acute (égu) accent: ['x] Additionally, the author has spelled certain words inconsistently. Those have been adjusted to be consistent where possible. Examples of such Chapter I 2 adjustments are as follows: From To Northwestern North-western Southwards Southward Programme Program re-introduced reintroduced practise practice Lotos Lotus Ju-Chên Juchên cooperate co-operate life-time lifetime man-power manpower favor favour etc. In general such changes are made to be consistent with the predominate usage in the text, or if there was not a predominate spelling, to the more modern.] A HISTORY OF CHINA by WOLFRAM EBERHARD CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE EARLIEST TIMES Chapter I : PREHISTORY 1 Sources for the earliest history 2 The Peking Man 3 The Palaeolithic Age 4 The Neolithic Age 5 The eight principal prehistoric cultures 6 The Yang-shao culture 7 The Lung-shan culture 8 The first petty States in Shansi Chapter II 3 Chapter II : THE SHANG DYNASTY (c.