Judicial Ethics Benchguide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

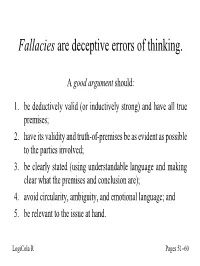

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II Reasoning is the best guide we have to the truth....Those who offer alternatives to reason are either mere hucksters, mere claimants to the throne, or there's a case to be made for them; and of course, that is an appeal to reason. Michael Scriven, Reasoning Why don’t you ever see a headline, “Psychic wins lottery”? Internet Joke News Item, June 16, 2010: A six story statue of Jesus in Monroe city, Ohio was struck by lightning and destroyed. An adult book store across the street was untouched. Introduction In the last chapter we examined one of the major causes of poor reasoning, getting off track and not focusing on the issues related to a conclusion. In our general discussion of arguments (Chapters 1-3), however, we saw that arguments can be weak in two other ways: 1. In deductive reasoning, arguments can be valid, but have false or questionable premises, or in both deductive and inductive reasoning, arguments may involve language tricks that mislead us into presuming evidence is being offered in the premises when it is not. 2. In weak inductive arguments, arguments can have true and relevant premises but those premises can be insufficient to justify a conclusion as a reliable guide to the future. Fallacies that use deductive valid reasoning, but have premises that are questionable or are unfair in some sense in the truth claims they make, we will call fallacies of questionable premise. As a subset of fallacies of questionable premise, fallacies that use tricks in the way the premises are presented, such that there is a danger of presuming evidence has been offered when it has not, we will call fallacies of presumption. -

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4 Jeremy Avigad, Robert Y. Lewis, and Floris van Doorn Sep 10, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Mathematical Proof ............................................ 1 1.2 Symbolic Logic .............................................. 2 1.3 Interactive Theorem Proving ....................................... 4 1.4 The Semantic Point of View ....................................... 5 1.5 Goals Summarized ............................................ 6 1.6 About this Textbook ........................................... 6 2 Propositional Logic 7 2.1 A Puzzle ................................................. 7 2.2 A Solution ................................................ 7 2.3 Rules of Inference ............................................ 8 2.4 The Language of Propositional Logic ................................... 15 2.5 Exercises ................................................. 16 3 Natural Deduction for Propositional Logic 17 3.1 Derivations in Natural Deduction ..................................... 17 3.2 Examples ................................................. 19 3.3 Forward and Backward Reasoning .................................... 20 3.4 Reasoning by Cases ............................................ 22 3.5 Some Logical Identities .......................................... 23 3.6 Exercises ................................................. 24 4 Propositional Logic in Lean 25 4.1 Expressions for Propositions and Proofs ................................. 25 4.2 More commands ............................................ -

Read in Full (PDF File)

THE HOLY GRAIL: IN PURSUIT OF THE DISSERTATION PROPOSAL Michael Watts Institute of International Studies University of California, Berkeley “[T]here is too little emphasis ... on what it means to do independent research” -William Bowen and Neil Rudenstein In Pursuit of the Ph.D. 1992 Introduction One of the great curiosities of academia is that the art of writing a research proposal–arguably one of the most difficult and demanding tasks confronting any research student–is so weakly institutionalized within graduate programs. The same, incidentally, might be said of fieldwork, whether the site is a village in northern Uganda or an archive in Pittsburgh. My experience is that fieldwork has all of the aura (and anxiety) of any rite of passage. But with a difference. It is a Darwinian learning-by- doing ordeal for which there is presumed to be no body of preparatory knowledge that can be passed on in advance; those that succeed return, and those that don’t are never seen again. It is perhaps for such reasons that Bowen and Rudenstein in their important book In Pursuit of the Ph.D. see the period between the end of coursework and the engagement of a dissertation topic as one of the most fraught and difficult in graduate formation. The selection of a topic they say is ‘a formidable task’, and students must be–but in practice rarely are in the social sciences and the humanities–encouraged to engage with their dissertation project in their first and second years. All of this is to say that the transition–another rite of passage–from course work to dissertation project is often paralyzing (“How exactly am I going to operationalize my crypto-Foucauldian study of the micro-physics of political power in San Francsico’s credit unions”?) and typically a source of bewilderment, anxiety and yes, even depression. -

Alabama State University Department of Languages and Literatures

ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES COURSE SYLLABUS PHILOSOPHY 201 LOGICAL REASONING (PHL 201) (Revised 10/20/04 – Dr. Daniel Keller.) I. Faculty Listing: PHL 201: Logical Reasoning (3 credit hours) II. Description: To satisfactorily complete the course, a student must earn a grade of “C.” The course is designed to help students assess information and arguments and to improve their ability to reason in a clear and logical way. The course concentrates specifically on helping students learn some of the various uses of languages, understand how different kinds of inferences are drawn, and learn to recognize fallacies of ambiguity, presumption, and relevance. III. Purpose: Many students do not reason soundly and do not distinguish correct from incorrect reasoning. Hence, the aim of this course is to give students experience in learning to recognize and evaluate arguments; it also aims at teaching them to construct arguments that are reasonable and defensible. It is designed as a basic course to improve the reasoning skills of students. After completing this course successfully, students should show improvements in reading comprehension, writing, and test- taking skills. IV. Course Objectives: 1. Comprehend concepts 1-9 on the attached list. a) Define each concept b) Identify the meaning of each concept as it applies to logic. 2. Comprehend how these concepts function in logical reasoning. a) Given examples from the text of each concept, correctly identify the concept. b) Given new examples of each concept, correctly identify the concept. 3. Comprehend concepts 10-16 on the attached list. a) Define the concepts b) Identify the meaning of the concept as it applies to logic. -

MGF1121 Course Outline

MGF1121 Course Outline Introduction to Logic............................................................................................................. (3) (P) Description: This course is a study of both the formal and informal nature of human thought. It includes an examination of informal fallacies, sentential symbolic logic and deductive proofs, categorical propositions, syllogistic arguments and sorites. General Education Learning Outcome: The primary General Education Learning Outcome (GELO) for this course is Quantitative Reasoning, which is to understand and apply mathematical concepts and reasoning, and analyze and interpret various types of data. The GELO will be assessed through targeted questions on either the comprehensive final or an outside assignment. Prerequisite: MFG1100, MAT1033, or MAT1034 with a grade of “C” or better, OR the equivalent. Rationale: In order to function effectively and productively in an increasingly complex democratic society, students must be able to think for themselves to make the best possible decisions in the many and varied situations that will confront them. Knowledge of the basic concepts of logical reasoning, as offered in this course, will give students a firm foundation on which to base their decision-making processes. Students wishing to major in computer science, philosophy, mathematics, engineering and most natural sciences are required to have a working knowledge of symbolic logic and its applications. Impact Assessment: Introduction to Logic provides students with critical insight -

On What We Know We Don't Know

On What We Know We Don't Know Explanation, Theory, Linguistics, and How Questions Shape Them On What We Know We Don't Know Explanation, Theory, Linguistics, and How Questions Shape Them Sylvain Bromberger The University of Center for the Study of Chicago Press Language and Information Chicago and London Stanford The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London c 1992 by the Center for the Study of Language and Information Leland Stanford Junior University All rights reserved. Published 1992 Printed in the United States of America 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 92 5 4 3 2 1 CIP data and other information appear at the end of the book To the memory of Aristides de Sousa Mendes Portuguese Consul in Bordeaux in June 1940 with gratitude Contents Introduction 1 1 An Approach to Explanation 18 2 A Theory about the Theory of Theory and about the Theory of Theories 52 3 Why-Questions 75 4 Questions 101 5 Science and the Forms of Ignorance 112 6 Rational Ignorance 128 7 What We Don't Know When We Don't Know Why 145 8 Types and Tokens in Linguistics 170 9 The Ontology of Phonology 209 with Morris Halle Bibliography 229 vii Introduction The nine papers in this book cover topics as diverse as the nature of explanation, the ambiguity of the word theory, the varieties of ig- norance, the limits of rationality in the choice of questions, and the ontology of linguistics. Each is self-contained and can be read inde- pendently of the others. -

Master List of Logical Fallacies

Master List of Logical Fallacies Fallacies are fake or deceptive arguments, arguments that prove nothing. Fallacies often seem superficially sound, and far too often have immense persuasive power, even after being clearly exposed as false. Fallacies are not always deliberate, but a good scholar’s purpose is always to identify and unmask fallacies in arguments. Ad Hominem Argument: Also, "personal attack," "poisoning the well." The fallacy of attempting to refute an argument by attacking the opposition’s personal character or reputation, using a corrupted negative argument from ethos. E.g., "He's so evil that you can't believe anything he says." See also Guilt by Association. Also applies to cases where valid opposing evidence and arguments are brushed aside without comment or consideration, as simply not worth arguing about. Appeal to Closure. The contemporary fallacy that an argument, standpoint, action or conclusion must be accepted, no matter how questionable, or else the point will remain unsettled and those affected will be denied "closure." This refuses to recognize the truth that some points will indeed remain unsettled, perhaps forever. (E.g., "Society would be protected, crime would be deterred and justice served if we sentence you to life without parole, but we need to execute you in order to provide some sense of closure.") (See also "Argument from Ignorance," "Argument from Consequences.") Appeal to Heaven: (also Deus Vult, Gott mit Uns, Manifest Destiny, the Special Covenant). An extremely dangerous fallacy (a deluded argument from ethos) of asserting that God (or a higher power) has ordered, supports or approves one's own standpoint or actions so no further justification is required and no serious challenge is possible. -

Critical Reasoning and Writing

CRITICAL REASONING AND WRITING Noah Levin Golden West College Book: Critical Reasoning and Writing (Levin et al.) Cross Library Transclusion template('CrossTransclude/Web',{'Library':'chem','PageID':170365}); TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1: INTRODUCTION TO CRITICAL THINKING, REASONING, AND LOGIC What is thinking? It may seem strange to begin a logic textbook with this question. ‘Thinking’ is perhaps the most intimate and personal thing that people do. Yet the more you ‘think’ about thinking, the more mysterious it can appear. Many people believe that logic is very abstract, dispassionate, complicated, and even cold. But in fact the study of logic is nothing more intimidating or obscure than this: the study of good thinking. 1.1: PRELUDE TO CHAPTER 1.2: INTRODUCTION AND THOUGHT EXPERIMENTS- THE TROLLEY PROBLEM 1.3: TRUTH AND ITS ROLE IN ARGUMENTATION - CERTAINTY, PROBABILITY, AND MONTY HALL 1.4: DISTINCTION OF PROOF FROM VERIFICATION; OUR BIASES AND THE FORER EFFECT 1.5: THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD 1.6: DIAGRAMMING THOUGHTS AND ARGUMENTS - ANALYZING NEWS MEDIA 1.7: CREATING A PHILOSOPHICAL OUTLINE 2: LANGUAGE - MEANING AND DEFINITION Rational people ought to concede he was right about one thing: many disagreements stem from linguistic problems. To resolve this, we simply (though it’s not actually simple) must use language clearly and precisely. If we eliminate all linguistic issues, then we’re left with the more meaningful philosophical problems, and real arguments can now happen since we know exactly what we’re talking about. 2.1: TECHNIQUES OF DEFINING- “SEMANTICS” VS “SYNTAX” AND AVOIDING MORE AMBIGUITY 2.2: CRITERIA FOR FRAMING DEFINITIONS- IT’S ALL ABOUT CONTEXT AND AUDIENCE 2.3: DEFINING TERMS APPROPRIATELY 2.4: COGNITIVE AND EMOTIVE MEANING - ABORTION AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT 2.5: FUNCTIONS OF LANGUAGE AND PRECISION IN SPEECH 2.6: DEFINING TERMS- TYPES AND PURPOSES OF DEFINITIONS 3: INFORMAL FALLACIES - MISTAKES IN REASONING What is a fallacy? Simply put, a fallacy is an error in reasoning. -

Front Matter

72 Complex Question A.G. Holdier George Walker Bush: great president or the greatest president? I’ll just put you down for great. Stephen Colbert Commonly referred to as a “loaded” question, the fallacy of the complex question (CQ) appears in two varieties: the implicit form distracts an inter- locutor by assuming the truth of an unproven premise and shifting the focus of the argument in an unfounded direction, while the explicit form collapses two distinct questions into a single question such that a single answer would appear to satisfy both inquiries. Although it is possible for a philosopher to commit this fallacy accidentally, its common use as an intentional tactic by debaters and investigators has also earned this example of faulty reasoning the title of the “interrogator’s fallacy,” with the classic example being that of a journalist asking a senator, “Have you stopped beating your wife?” – a question that implicitly presupposes without justification that the senator has actually beaten his wife at some point in the past. If the senator fails to recognize the fallacious thinking when he answers the CQ, he may uninten- tionally appear to admit that he is guilty of a crime of which he may be innocent. The explicit variety of CQ is far easier to identify and is typically not wielded as an argumentative tool but is often played for laughs; when a talk Bad Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Fallacies in Western Philosophy, First Edition. Edited by Robert Arp, Steven Barbone, and Michael Bruce. © 2019 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Published 2019 by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. -

What Is Circular Reasoning?

Robert D. Coleman, PhD © 2006 [email protected] What Is Circular Reasoning? Logical fallacies are a type of error in reasoning, errors which may be recognized and corrected by observant thinkers. There are a large number of informal fallacies that are cataloged, and some have multiple names. The frequency of occurrence is one way to rank the fallacies. The ten most-frequent fallacies probably cover the overwhelming majority of illogical reasoning. With a Pareto effect, 20% of the major fallacies might account for 80% of fallacious reasoning. One of the more common fallacies is circular reasoning, a form of which was called “begging the question” by Aristotle in his book that named the fallacies of classical logic. The fallacy of circular reasoning occurs when the conclusion of an argument is essentially the same as one of the premises in the argument. Circular reasoning is an inference drawn from a premise that includes the conclusion, and used to prove the conclusion. Definitions of words are circular reasoning, but they are not inference. Inference is the deriving of a conclusion in logic by either induction or deduction. Circular reasoning can be quite subtle, can be obfuscated when intentional, and thus can be difficult to detect. Circular reasoning as a fallacy refers to reasoning in vicious circles or vicious circular reasoning, in contrast to reasoning in virtuous circles or virtuous circular reasoning. Virtuous circular reasoning is sometimes used for pedagogical purposes, such as in math to show that two different statements are equivalent expressions of the same thing. In a logical argument, viciously circular reasoning occurs when one attempts to infer a conclusion that is based upon a premise that ultimately contains the conclusion itself. -

Introduction to Logic: Problems and Solutions

Introduction to Logic: Problems and solutions A. V. Ravishankar Sarma Email: [email protected] January 5, 2015 Contents I Informal Logic 5 1 Theory of Argumentation 7 1.1 Lecture 1: Identification of Arguments . 7 1.2 Lecture 2: Non- arguments . 7 1.2.1 Identify arguments from the following passages . 7 1.3 Lecture 3: Types of Arguments: Deductive vs Inductive . 9 1.4 Lecture 4:Nature and Scope of Deductive and Inductive Arguments . 9 1.4.1 Is the following argument best classified as deductive or inductive? . 9 1.5 Lecture 5: Truth, Validity and Soundness . 10 1.6 Lecture 6: Strength of Inductive arguments, Counter example method . 10 1.6.1 Construct counter examples for the following invalid arguments . 10 1.6.2 Evaluate the following Deductive and Inductive Arguments . 10 1.6.3 Answers . 11 1.7 Lecture 7: Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation . 12 1.7.1 Identify claim, support, warrant, rebuttal in the following arguments 12 2 Fallacies 13 2.1 Lecture 8: Identification of Formal and Informal Fallacies . 13 2.1.1 Determine whether the fallacies committed by the following argu- ments are formal fallacies or informal fallacies. 13 2.2 Lecture 9: Informal Fallacies: Fallacies of relevance . 14 2.3 Lecture 10: Fallacies of Weak Induction and Fallacies arising out of ambiguity in Language . 16 2.3.1 Identify the fallacies of weak induction committed by the following arguments, giving a brief explanation for your answer. If no fallacy is committed, write no fallacy. 16 2.3.2 Identify the fallacies of presumption, ambiguity, and grammatical anal- ogy committed by the following arguments, giving a brief explanation for your answer.