On What We Know We Don't Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Would ''Direct Realism'' Resolve the Classical Problem of Induction?

NOU^S 38:2 (2004) 197–232 Would ‘‘Direct Realism’’ Resolve the Classical Problem of Induction? MARC LANGE University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill I Recently, there has been a modest resurgence of interest in the ‘‘Humean’’ problem of induction. For several decades following the recognized failure of Strawsonian ‘‘ordinary-language’’ dissolutions and of Wesley Salmon’s elaboration of Reichenbach’s pragmatic vindication of induction, work on the problem of induction languished. Attention turned instead toward con- firmation theory, as philosophers sensibly tried to understand precisely what it is that a justification of induction should aim to justify. Now, however, in light of Bayesian confirmation theory and other developments in epistemology, several philosophers have begun to reconsider the classical problem of induction. In section 2, I shall review a few of these developments. Though some of them will turn out to be unilluminating, others will profitably suggest that we not meet inductive scepticism by trying to justify some alleged general principle of ampliative reasoning. Accordingly, in section 3, I shall examine how the problem of induction arises in the context of one particular ‘‘inductive leap’’: the confirmation, most famously by Henrietta Leavitt and Harlow Shapley about a century ago, that a period-luminosity relation governs all Cepheid variable stars. This is a good example for the inductive sceptic’s purposes, since it is difficult to see how the sparse background knowledge available at the time could have entitled stellar astronomers to regard their observations as justifying this grand inductive generalization. I shall argue that the observation reports that confirmed the Cepheid period- luminosity law were themselves ‘‘thick’’ with expectations regarding as yet unknown laws of nature. -

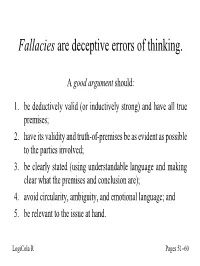

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Before Refraining: Concepts for Agency Author(S): Nuel Belnap Source: Erkenntnis (1975-), Vol

Before Refraining: Concepts for Agency Author(s): Nuel Belnap Source: Erkenntnis (1975-), Vol. 34, No. 2 (Mar., 1991), pp. 137-169 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20012334 Accessed: 28/05/2009 14:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springer. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Erkenntnis (1975-). http://www.jstor.org NUEL BELNAP BEFORE REFRAINING: CONCEPTS FOR AGENCY ABSTRACT. A structure is described that can serve as a foundation for a semantics for a modal agentive construction such as "a sees to it that Q" ([a sur.Q]). -

Paul Feyerabend

Against Method Fourth Edition Paul Feyerabend VERSO London • New York Analytical Index Being a Sketch of the Main Argument Introdnction 1 Science is an essentially anarchic enterprise: theoretical anarchism is more humanitarian and more likely to encourage progress than its law-and-order alternatives. 1 7 This is shown both by an examination of historical episodes and by an abstract analysis of the relation between idea and action. The only principle that does not inhibit progress is: anything goes. 2 13 For example, we may use hypotheses that contradict well-confirmed theories and/or well-established experimental results. We may advance science by proceeding counterinductively. 3 17 The consistency condition which demands that new hypotheses agree with accepted theories is unreasonable because it preserves the older theory, and not the better theory. Hypotheses contradicting well-confirmed theories give us evidence that cannot be obtained in any other way. Proliferation of theories is beneficial for science, while uniformity impairs its critical power. Uniformity also endangers the free development of the individual. 4 ~ There is no idea, however ancient and absurd, that is not capable of improving our knowledge. The whole history of thought is absorbed into science and is used for improving every single theory. Nor is political interference rejected. It may be needed to overcome the chauvinism of science that resists alternatives to the status quo. xxx ANAL YTICAL INDEX 5 33 No theory ever agrees with all the facts in its domain, yet it is not always the theory that is to blame. Facts are constituted by older ideologies, and a clash between facts and theories may be proof ofprogress. -

CURRICULUM VITAE January, 2018 DANIEL GARBER

CURRICULUM VITAE January, 2018 DANIEL GARBER Position: A. Watson Armour III University Professor of Philosophy Address: Department of Philosophy 1879 Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006 Address (September 2017-July 2018) Institut d’études avancées 17, quai d’Anjou 75004 Paris France Telephone: 609-258-4307 (voice) 609-258-1502 (FAX) 609-258-4289 (Departmental office) Email: [email protected] Erdös number: 16 EDUCATIONAL RECORD Harvard University, 1967-1975 A.B. in Philosophy, 197l A.M. in Philosophy, 1974 Ph.D. in Philosophy, 1975 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Princeton University 2002- Professor of Philosophy and Associated Faculty, Program in the History of Science 2005-12 Chair, Department of Philosophy 2008-09 Old Dominion Professor 2009- Associated Faculty, Department of Politics 2009-16 Stuart Professor of Philosophy Garber -2- 2016- A. Watson Armour III University Professor of Philosophy University of Chicago 1995-2002 Lawrence Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor in Philosophy, the Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science, the Morris Fishbein Center for Study of History of Science and Medicine and the College 1986-2002 Professor 1982-86 Associate Professor (with tenure) 1975-82 Assistant Professor 1998-2002 Chairman, Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science (formerly Conceptual Foundations of Science) 2001 Acting Chairman, Department of Philosophy 1995-98 Associate Provost for Education and Research 1994-95 Chairman, Conceptual Foundations of Science 1987-94 Chairman, Department of Philosophy Harvard College 1972-75 Teaching Assistant and Tutor University of Minnesota, Spring 1979, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy Johns Hopkins University, 1980-1981, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy Princeton University 1982-1983 Visiting Associate Professor of Philosophy Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, 1985-1986, Member École Normale Supérieure (Lettres) (Lyon, France), November 2000, Professeur invitée. -

1 Truth and Falsehood

Trends in Logic 36 Wansing Shramko · Trends in Logic 36 Yaroslav Shramko · Heinrich Wansing Truth and Falsehood An Inquiry into Generalized Logical Values The book presents a thoroughly elaborated logical theory of generalized truth values understood as subsets of some established set of (basic) entities. After elucidating the importance of the very notion of a truth value in logic and philosophy, the authors ex- amine some possible ways of generalizing this notion. The useful four-valued logic of first-degree entailment by Nuel Belnap and Michael Dunn and the notion of a bilattice Yaroslav Shramko (a lattice of truth values with two ordering relations) constitute the basis for further generalizations. By doing so, the authors elaborate the idea of a multilattice and, most Heinrich Wansing notably, a trilattice of truth values – a specific algebraic structure with an information ordering and two distinct logical orderings, one for truth and another for falsity. Each logical order not only induces its own logical vocabulary, but also determines its own entailment relation. Both semantic and syntactic ways of formalizing these relations by constructing various logical calculi are considered Truth This book is an exceptional contribution to philosophical logic; no one who thinks about truth values should miss it. Taking Truth and Falsehood as objects in Frege's way, the 1 authors serve up a compelling combination of (1) authoritative, encyclopedic, and philo- and Falsehood Truth sophically sensitive history, (2) a careful and persuasive presentation of their beautiful and superuseful theory of sixteen (not just algebraic but really logical) truth values structured and Falsehood as a trilattice, and (3) a dazzling array of related conceptually motivated formal develop- ments that bring the reader to the forefront of current research. -

Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II Reasoning is the best guide we have to the truth....Those who offer alternatives to reason are either mere hucksters, mere claimants to the throne, or there's a case to be made for them; and of course, that is an appeal to reason. Michael Scriven, Reasoning Why don’t you ever see a headline, “Psychic wins lottery”? Internet Joke News Item, June 16, 2010: A six story statue of Jesus in Monroe city, Ohio was struck by lightning and destroyed. An adult book store across the street was untouched. Introduction In the last chapter we examined one of the major causes of poor reasoning, getting off track and not focusing on the issues related to a conclusion. In our general discussion of arguments (Chapters 1-3), however, we saw that arguments can be weak in two other ways: 1. In deductive reasoning, arguments can be valid, but have false or questionable premises, or in both deductive and inductive reasoning, arguments may involve language tricks that mislead us into presuming evidence is being offered in the premises when it is not. 2. In weak inductive arguments, arguments can have true and relevant premises but those premises can be insufficient to justify a conclusion as a reliable guide to the future. Fallacies that use deductive valid reasoning, but have premises that are questionable or are unfair in some sense in the truth claims they make, we will call fallacies of questionable premise. As a subset of fallacies of questionable premise, fallacies that use tricks in the way the premises are presented, such that there is a danger of presuming evidence has been offered when it has not, we will call fallacies of presumption. -

The Epistemology of Testimony

Pergamon Stud. His. Phil. Sci., Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 1-31, 1998 0 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved Printed in Great Britain 0039-3681/98 $19.004-0.00 The Epistemology of Testimony Peter Lipton * 1. Introduction Is there anything you know entirely off your own bat? Your knowledge depends pervasively on the word of others. Knowledge of events before you were born or outside your immediate neighborhood are the obvious cases, but your epistemic dependence on testimony goes far deeper that this. Mundane beliefs-such as that the earth is round or that you think with your brain-almost invariably depend on testimony, and even quite personal facts-such as your birthday or the identity of your biological parents--can only be known with the help of others. Science is no refuge from the ubiquity of testimony. At least most of the theories that a scientist accepts, she accepts because of what others say. The same goes for almost all the data, since she didn’t perform those experiments herself. Even in those experiments she did perform, she relied on testimony hand over fist: just think of all those labels on the chemicals. Even her personal observations may have depended on testimony, if observation is theory-laden, since those theories with which it is laden were themselves accepted on testimony. Even if observation were not theory-laden, the testimony-ladenness of knowledge should be beyond dispute. We live in a sea of assertions and little if any of our knowledge would exist without it. If the role of testimony in knowledge is so vast, why is its role in the history of epistemology so slight? Why doesn’t the philosophical canon sparkle with titles such as Meditations on Testimony, A Treatise Concerning Human Testimony, and Language, Truth and Testimony? The answer is unclear. -

The Idea of a Religious Social Science

The Idea Of A Religious Social Science Professor Khosrow Bagheri Noaparast University of Tehran Distributed by Alhoda International Publication and Distribution No 766 Vali-e-Asr Ave. Tehran, Iran Tel: 0098 21 88897661 www.alhoda.ir email: [email protected] Copywright 2009 by Alhoda All rights reserved First edition 2009 ISBN 978-964-439-064-7 2 Contents Preface Chapter 1: Science: Positivist and Post-positivist Views Introduction 1.1. Positivist Account of Science 1.2. Post-positivist Challenges 1.2.1. Integration of Science and Metaphysics 1.2.2. Extent of Metaphysics’ Impact on Science 1.2.3. Integration of Theory and Observation 1.2.4. Integration of Fact and Value 1.2.5. Non-linear Progress of Science 1.2.6. Impact of Science on Metaphysics Chapter 2: Religion 2.1. Encyclopedic Theory of Religion 2.2. Functional Theory of Religion 2.3. Theory of Selectivity of Religion 2.3.1. Distinctive Nature of Religious Knowledge 2.3.2. Characteristics of Religion and Religious Knowledge Chapter 3: Meaninglessness and Meaningfulness in Religious Science Introduction 3.1. Epistemological Monism and Religious Science 3.1.1. Logical Positivism: Meaninglessness of Religious Science 3.1.2. The Significance of Positivists’ View 3.1.3. Pragmatism: Meaninglessness of Religious Science 3.1.4. The Significance of Pragmatists’ View 3.2. Pluralism and Religious Science 3.2.1. Contrastive Pluralism: Meaninglessness of Religious Science 3.2.2. Significance of Contrastive Pluralism 3.2.3 Overlap Pluralism: Meaningfulness of Religious Science Chapter 4: True and False in Religious Science Introduction 4.1. The Inferential Approach and its Critique 4.1.1. -

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4 Jeremy Avigad, Robert Y. Lewis, and Floris van Doorn Sep 10, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Mathematical Proof ............................................ 1 1.2 Symbolic Logic .............................................. 2 1.3 Interactive Theorem Proving ....................................... 4 1.4 The Semantic Point of View ....................................... 5 1.5 Goals Summarized ............................................ 6 1.6 About this Textbook ........................................... 6 2 Propositional Logic 7 2.1 A Puzzle ................................................. 7 2.2 A Solution ................................................ 7 2.3 Rules of Inference ............................................ 8 2.4 The Language of Propositional Logic ................................... 15 2.5 Exercises ................................................. 16 3 Natural Deduction for Propositional Logic 17 3.1 Derivations in Natural Deduction ..................................... 17 3.2 Examples ................................................. 19 3.3 Forward and Backward Reasoning .................................... 20 3.4 Reasoning by Cases ............................................ 22 3.5 Some Logical Identities .......................................... 23 3.6 Exercises ................................................. 24 4 Propositional Logic in Lean 25 4.1 Expressions for Propositions and Proofs ................................. 25 4.2 More commands ............................................ -

The Oberlin Colloquium in Philosophy: Program History

The Oberlin Colloquium in Philosophy: Program History 1960 FIRST COLLOQUIUM Wilfrid Sellars, "On Looking at Something and Seeing it" Ronald Hepburn, "God and Ambiguity" Comments: Dennis O'Brien Kurt Baier, "Itching and Scratching" Comments: David Falk/Bruce Aune Annette Baier, "Motives" Comments: Jerome Schneewind 1961 SECOND COLLOQUIUM W.D. Falk, "Hegel, Hare and the Existential Malady" Richard Cartwright, "Propositions" Comments: Ruth Barcan Marcus D.A.T. Casking, "Avowals" Comments: Martin Lean Zeno Vendler, "Consequences, Effects and Results" Comments: William Dray/Sylvan Bromberger PUBLISHED: Analytical Philosophy, First Series, R.J. Butler (ed.), Oxford, Blackwell's, 1962. 1962 THIRD COLLOQUIUM C.J. Warnock, "Truth" Arthur Prior, "Some Exercises in Epistemic Logic" Newton Garver, "Criteria" Comments: Carl Ginet/Paul Ziff Hector-Neri Castenada, "The Private Language Argument" Comments: Vere Chappell/James Thomson John Searle, "Meaning and Speech Acts" Comments: Paul Benacerraf/Zeno Vendler PUBLISHED: Knowledge and Experience, C.D. Rollins (ed.), University of Pittsburgh Press, 1964. 1963 FOURTH COLLOQUIUM Michael Scriven, "Insanity" Frederick Will, "The Preferability of Probable Beliefs" Norman Malcolm, "Criteria" Comments: Peter Geach/George Pitcher Terrence Penelhum, "Pleasure and Falsity" Comments: William Kennick/Arnold Isenberg 1964 FIFTH COLLOQUIUM Stephen Korner, "Some Remarks on Deductivism" J.J.C. Smart, "Nonsense" Joel Feinberg, "Causing Voluntary Actions" Comments: Keith Donnellan/Keith Lehrer Nicholas Rescher, "Evaluative Metaphysics" Comments: Lewis W. Beck/Thomas E. Patton Herbert Hochberg, "Qualities" Comments: Richard Severens/J.M. Shorter PUBLISHED: Metaphysics and Explanation, W.H. Capitan and D.D. Merrill (eds.), University of Pittsburgh Press, 1966. 1965 SIXTH COLLOQUIUM Patrick Nowell-Smith, "Acts and Locutions" George Nakhnikian, "St. Anselm's Four Ontological Arguments" Hilary Putnam, "Psychological Predicates" Comments: Bruce Aune/U.T. -

Carnap's Pragmatism

CARNAP’S PRAGMATISM by Jonathan Surovell B.A. in Philosophy, McGill University, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jonathan Surovell It was defended on June 13, 2013 and approved by Thomas Ricketts Mark Wilson Nuel Belnap James Shaw Steve Awodey Dissertation Director: Thomas Ricketts ii CARNAP’S PRAGMATISM Jonathan Surovell, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The dissertation aims to vindicate central elements of the logical empiricist ideal of a scientific philosophy through an interpretation and defense of what I call ‘Carnap’s pragmatism’. The latter is the practical decision to regard scientific language as an instrument for the derivation of accurate, intersubjective, observational knowledge. My account adds to the current state of Carnapian philosophy in two respects. First, Carnap’s pragmatism is fundamental in a sense that is not generally appreci- ated: while many commentators have noted that Carnap views verificationism as a pragmatic proposal, such discussions lack sharp formulations of the underlying prag- matist values or of their connection to verificationism. Second, the lack of attention to pragmatism has led to a truncated picture of the Principle of Tolerance. Toler- ance holds that the scientifically oriented philosopher can choose whichever linguistic tools are useful, regardless of whether they “correctly represent reality”. This aspect of tolerance is typically understood in terms of a “relativity to language”: since lan- guage provides the semantic or evidential rules for inquiry language cannot itself be subject to such rules.