Defense Through the Exposure of Fallacies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constantinos Georgiou Athanasopoulos

Constantinos Athanasopoulos, 1 Constantinos Georgiou Athanasopoulos Supervisor Mary Haight Title The Metaphysics of Intentionality: A Study of Intentionality focused on Sartre's and Wittgenstein's Philosophy of Mind and Language. Submission for PhD Department of Philosophy University of Glasgow JULY 1995 ProQuest Number: 13818785 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818785 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UKVERSITT LIBRARY Constantinos Athanasopoulos, 2 ABSTRACT With this Thesis an attempt is made at charting the area of the Metaphysics of Intentionality, based mainly on the Philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre. A Philosophical Analysis and an Evaluation o f Sartre’s Arguments are provided, and Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality is supported by recent commentaries on the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality is proposed, with few improvements by the author, as the only modem theory of the mind that can oppose effectively the advance of AI and physicalist reductivist attempts in Philosophy of Mind and Language. Discussion includes Sartre’s critique of Husserl, the relation of Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality to Realism, its applicability in the Theory of the Emotions, and recent theories of Intentionality such as Mohanty’s, Aquilla’s, Searle’s, and Harney’s. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

Colecția Erorilor De Argumentare

Colecția erorilor de argumentare 62 dintre cele mai comune erori de argumentare Este extrem de ușor să comiți o eroare atunci când ai sentimente puternice cu privire la subiectul tău - dacă o concluzie ți se pare evidentă, este mai probabil să presupui că este adevărată și să fii neglijent cu dovezile, spre exemplu. Pentru a te ajuta să vezi cum oamenii fac în mod frecvent aceste greșeli, acest document folosește o serie de exemple comune în spațiul public - argumente despre subiecte precum avortul, controlul armelor, pedeapsa cu moartea, căsătoria persoanelor de același sex, vaccinare etc. Scopul acestui document, totuși, nu este să argumenteze pentru o poziție cu privire la oricare dintre aceste probleme; mai degrabă, este pentru a ilustra raționamentul slab din spatele acestora; vei observa, probabil, că unele afirmații din exemplele alese pentru a ilustra aceste erori sunt, în mod evident, false. Dacă știi care sunt erorile, le poți evita în argumentele tale. Acest aspect îți oferă și o bază pentru evaluarea și criticarea argumentelor celorlalți. apelul la probabilitate O AFIRMAȚIE CONSIDERATĂ VALIDĂ DOAR PENTRU CĂ S-AR PUTEA SĂ FIE ADEVĂRATĂ. "CEVA S-AR PUTEA SĂ MEARGĂ PROST. apelul la PRIN URMARE, VA MERGE PROST" probabilitate ARGUMENT DIN EROARE SAU eroare în eroare PRESUPUNEREA CĂ, DACĂ UN ARGUMENT ESTE ERONAT, ATUNCI CONCLUZIA ESTE FALSĂ. "TOM: VORBESC ENGLEZĂ. PRIN URMARE, SUNT ENGLEZ. BEN: AMERICANII ȘI CANADIENII, PRINTRE ALȚII, VORBESC ENGLEZĂ. PRESUPUNÂND eroare în CĂ A VORBI ÎN ENGLEZĂ ȘI A FI ENGLEZ eroare MERG ÎNTOTDEAUNA ÎMPREUNĂ, TOCMAI AI COMIS O EROARE. PRIN URMARE, NU EȘTI ENGLEZ." BEN CONSIDERĂ CĂ BEN NU ESTE ENGLEZ DEOARECE ARGUMENTUL LUI ESTE ERONAT. -

Learning to Spot Common Fallacies

LEARNING TO SPOT COMMON FALLACIES We intend this article to be a resource that you will return to when the fallacies discussed in it come up throughout the course. Do not feel that you need to read or master the entire article now. We’ve discussed some of the deep-seated psychological obstacles to effective logical and critical thinking in the videos. This article sets out some more common ways in which arguments can go awry. The defects or fallacies presented here tend to be more straightforward than psychological obstacles posed by reasoning heuristics and biases. They should, therefore, be easier to spot and combat. You will see though, that they are very common: keep an eye out for them in your local paper, online, or in arguments or discussions with friends or colleagues. One reason they’re common is that they can be quite effective! But if we offer or are convinced by a fallacious argument we will not be acting as good logical and critical thinkers. Species of Fallacious Arguments The common fallacies are usefully divided into three categories: Fallacies of Relevance, Fallacies of Unacceptable Premises, and Formal Fallacies. Fallacies of Relevance Fallacies of relevance offer reasons to believe a claim or conclusion that, on examination, turn out to not in fact to be reasons to do any such thing. 1. The ‘Who are you to talk?’, or ‘You Too’, or Tu Quoque Fallacy1 Description: Rejecting an argument because the person advancing it fails to practice what he or she preaches. Example: Doctor: You should quit smoking. It’s a serious health risk. -

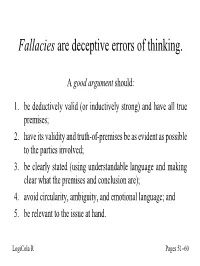

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

The Fallacy of Composition and Meta-Argumentation"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 10 May 22nd, 9:00 AM - May 25th, 5:00 PM Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation" Michel Dufour Sorbonne-Nouvelle, Institut de la Communication et des Médias Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Dufour, Michel, "Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta- argumentation"" (2013). OSSA Conference Archive. 49. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA10/papersandcommentaries/49 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro’s “The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation” MICHEL DUFOUR Department «Institut de la Communication et des Médias» Sorbonne-Nouvelle 13 rue Santeuil 75231 Paris Cedex 05 France [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION In his paper on the fallacy of composition, Maurice Finocchiaro puts forward several important theses about this fallacy. He also uses it to illustrate his view that fallacies should be studied in light of the notion of meta-argumentation at the core of his recent book (Finocchiaro, 2013). First, he expresses his puzzlement. Some authors have claimed that this fallacy is quite common (this is the ubiquity thesis) but it seems to have been neglected by scholars. -

Fallacies in Reasoning

FALLACIES IN REASONING FALLACIES IN REASONING OR WHAT SHOULD I AVOID? The strength of your arguments is determined by the use of reliable evidence, sound reasoning and adaptation to the audience. In the process of argumentation, mistakes sometimes occur. Some are deliberate in order to deceive the audience. That brings us to fallacies. I. Definition: errors in reasoning, appeal, or language use that renders a conclusion invalid. II. Fallacies In Reasoning: A. Hasty Generalization-jumping to conclusions based on too few instances or on atypical instances of particular phenomena. This happens by trying to squeeze too much from an argument than is actually warranted. B. Transfer- extend reasoning beyond what is logically possible. There are three different types of transfer: 1.) Fallacy of composition- occur when a claim asserts that what is true of a part is true of the whole. 2.) Fallacy of division- error from arguing that what is true of the whole will be true of the parts. 3.) Fallacy of refutation- also known as the Straw Man. It occurs when an arguer attempts to direct attention to the successful refutation of an argument that was never raised or to restate a strong argument in a way that makes it appear weaker. Called a Straw Man because it focuses on an issue that is easy to overturn. A form of deception. C. Irrelevant Arguments- (Non Sequiturs) an argument that is irrelevant to the issue or in which the claim does not follow from the proof offered. It does not follow. D. Circular Reasoning- (Begging the Question) supports claims with reasons identical to the claims themselves. -

Fitting Words

FITTING WORDS Answer Key SAMPLE James B. Nance, Fitting Words: Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student: Answer Key Copyright ©2016 by James B. Nance Version 1.0.0 Published by Roman Roads Media 739 S Hayes Street, Moscow, Idaho 83843 509-592-4548 | www.romanroadsmedia.com Cover design concept by Mark Beauchamp; adapted by Daniel Foucachon and Valerie Anne Bost. Cover illustration by Mark Beauchamp; adapted by George Harrell. Interior illustration by George Harrell. Interior design by Valerie Anne Bost. Printed in the United States of America. Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the New King James Version of the Bible, ©1979, 1980, 1982, 1984, 1988 by Thomas Nelson, Inc., Nashville, Tennessee. Scripture quotations marked NIV are from the the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scipture quotations marked ESV are from the English Standard Version copyright ©2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the author, except as provided by USA copyright law. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available on www.romanroadsmedia.com. ISBN-13: 978-1-944482-03-9 ISBN-10:SAMPLE 1-944482-03-2 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 FITTING WORDS Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student Answer Key JAMES B. -

10 Fallacies and Examples Pdf

10 fallacies and examples pdf Continue A: It is imperative that we promote adequate means to prevent degradation that would jeopardize the project. Man B: Do you think that just because you use big words makes you sound smart? Shut up, loser; You don't know what you're talking about. #2: Ad Populum: Ad Populum tries to prove the argument as correct simply because many people believe it is. Example: 80% of people are in favor of the death penalty, so the death penalty is moral. #3. Appeal to the body: In this erroneous argument, the author argues that his argument is correct because someone known or powerful supports it. Example: We need to change the age of drinking because Einstein believed that 18 was the right age of drinking. #4. Begging question: This happens when the author's premise and conclusion say the same thing. Example: Fashion magazines do not harm women's self-esteem because women's trust is not damaged after reading the magazine. #5. False dichotomy: This misconception is based on the assumption that there are only two possible solutions, so refuting one decision means that another solution should be used. It ignores other alternative solutions. Example: If you want better public schools, you should raise taxes. If you don't want to raise taxes, you can't have the best schools #6. Hasty Generalization: Hasty Generalization occurs when the initiator uses too small a sample size to support a broad generalization. Example: Sally couldn't find any cute clothes in the boutique and couldn't Maura, so there are no cute clothes in the boutique. -

334 CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES a Deductive Fallacy Is

CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES A deductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument necessarily follows from the truth of the premises given, when in fact that conclusion does not necessarily follow from those premises. An inductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument is made more probable by its relationship with the premises of the argument, when in fact it is not. We will cover two kinds of fallacies: formal fallacies and informal fallacies. An argument commits a formal fallacy if it has an invalid argument form. An argument commits an informal fallacy when it has a valid argument form but derives from unacceptable premises. A. Fallacies with Invalid Argument Forms Consider the following arguments: (1) All Europeans are racist because most Europeans believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans and all people who believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans are racist. (2) Since no dogs are cats and no cats are rats, it follows that no dogs are rats. (3) If today is Thursday, then I'm a monkey's uncle. But, today is not Thursday. Therefore, I'm not a monkey's uncle. (4) Some rich people are not elitist because some elitists are not rich. 334 These arguments have the following argument forms: (1) Some X are Y All Y are Z All X are Z. (2) No X are Y No Y are Z No X are Z (3) If P then Q not-P not-Q (4) Some E are not R Some R are not E Each of these argument forms is deductively invalid, and any actual argument with such a form would be fallacious. -

Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II Reasoning is the best guide we have to the truth....Those who offer alternatives to reason are either mere hucksters, mere claimants to the throne, or there's a case to be made for them; and of course, that is an appeal to reason. Michael Scriven, Reasoning Why don’t you ever see a headline, “Psychic wins lottery”? Internet Joke News Item, June 16, 2010: A six story statue of Jesus in Monroe city, Ohio was struck by lightning and destroyed. An adult book store across the street was untouched. Introduction In the last chapter we examined one of the major causes of poor reasoning, getting off track and not focusing on the issues related to a conclusion. In our general discussion of arguments (Chapters 1-3), however, we saw that arguments can be weak in two other ways: 1. In deductive reasoning, arguments can be valid, but have false or questionable premises, or in both deductive and inductive reasoning, arguments may involve language tricks that mislead us into presuming evidence is being offered in the premises when it is not. 2. In weak inductive arguments, arguments can have true and relevant premises but those premises can be insufficient to justify a conclusion as a reliable guide to the future. Fallacies that use deductive valid reasoning, but have premises that are questionable or are unfair in some sense in the truth claims they make, we will call fallacies of questionable premise. As a subset of fallacies of questionable premise, fallacies that use tricks in the way the premises are presented, such that there is a danger of presuming evidence has been offered when it has not, we will call fallacies of presumption.