Fallacies Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Logic to Rhetoric: a Contextualized Pedagogy for Fallacies

Current Issue From the Editors Weblog Editorial Board Editorial Policy Submissions Archives Accessibility Search Composition Forum 32, Fall 2015 From Logic to Rhetoric: A Contextualized Pedagogy for Fallacies Anne-Marie Womack Abstract: This article reenvisions fallacies for composition classrooms by situating them within rhetorical practices. Fallacies are not formal errors in logic but rather persuasive failures in rhetoric. I argue fallacies are directly linked to successful rhetorical strategies and pose the visual organizer of the Venn diagram to demonstrate that claims can achieve both success and failure based on audience and context. For example, strong analogy overlaps false analogy and useful appeal to pathos overlaps manipulative emotional appeal. To advance this argument, I examine recent changes in fallacies theory, critique a-rhetorical textbook approaches, contextualize fallacies within the history and theory of rhetoric, and describe a methodology for rhetorically reclaiming these terms. Today, fallacy instruction in the teaching of written argument largely follows two paths: teachers elevate fallacies as almost mathematical formulas for errors or exclude them because they don’t fit into rhetorical curriculum. Both responses place fallacies outside the realm of rhetorical inquiry. Fallacies, though, are not as clear-cut as the current practice of spotting them might suggest. Instead, they rely on the rhetorical situation. Just as it is an argument to create a fallacy, it is an argument to name a fallacy. This article describes an approach in which students must justify naming claims as successful strategies and/or fallacies, a process that demands writing about contexts and audiences rather than simply linking terms to obviously weak statements. -

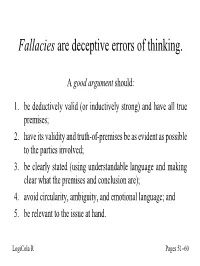

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

10 Fallacies and Examples Pdf

10 fallacies and examples pdf Continue A: It is imperative that we promote adequate means to prevent degradation that would jeopardize the project. Man B: Do you think that just because you use big words makes you sound smart? Shut up, loser; You don't know what you're talking about. #2: Ad Populum: Ad Populum tries to prove the argument as correct simply because many people believe it is. Example: 80% of people are in favor of the death penalty, so the death penalty is moral. #3. Appeal to the body: In this erroneous argument, the author argues that his argument is correct because someone known or powerful supports it. Example: We need to change the age of drinking because Einstein believed that 18 was the right age of drinking. #4. Begging question: This happens when the author's premise and conclusion say the same thing. Example: Fashion magazines do not harm women's self-esteem because women's trust is not damaged after reading the magazine. #5. False dichotomy: This misconception is based on the assumption that there are only two possible solutions, so refuting one decision means that another solution should be used. It ignores other alternative solutions. Example: If you want better public schools, you should raise taxes. If you don't want to raise taxes, you can't have the best schools #6. Hasty Generalization: Hasty Generalization occurs when the initiator uses too small a sample size to support a broad generalization. Example: Sally couldn't find any cute clothes in the boutique and couldn't Maura, so there are no cute clothes in the boutique. -

On Appeals to Nature and Their Use in the Public Controversy Over Genetically Modified Organisms Andrei Moldovan

Document generated on 09/25/2021 12:45 a.m. Informal Logic On Appeals to Nature and their Use in the Public Controversy over Genetically Modified Organisms Andrei Moldovan Volume 38, Number 3, 2018 Article abstract In this paper I discuss appeals to nature, a particular kind of argument that has URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1057048ar received little attention in argumentation theory. After a quick review of the DOI: https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v38i3.5050 existing literature, I focus on the use of such arguments in the public controversy over the acceptabil-ity of genetically-modified organisms in the See table of contents food industry. Those who reject this biotechnology invoke its unnatural character. Such arguments have re-ceived attention in bioethics, where they have been analyzed by distinguishing different meanings that “nature” and Publisher(s) “natural” might have. I argue that in many such appeals to nature the main deficiency of these arguments is semantic, in particular, that these words Informal Logic cannot be assigned a determi-nate meaning at all. In doing so, I rely on semantic externalism, a widely accepted theory of linguistic meaning. ISSN 0824-2577 (print) 2293-734X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Moldovan, A. (2018). On Appeals to Nature and their Use in the Public Controversy over Genetically Modified Organisms. Informal Logic, 38(3), 409–437. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v38i3.5050 Copyright (c), 2018 Andrei Moldovan This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II Reasoning is the best guide we have to the truth....Those who offer alternatives to reason are either mere hucksters, mere claimants to the throne, or there's a case to be made for them; and of course, that is an appeal to reason. Michael Scriven, Reasoning Why don’t you ever see a headline, “Psychic wins lottery”? Internet Joke News Item, June 16, 2010: A six story statue of Jesus in Monroe city, Ohio was struck by lightning and destroyed. An adult book store across the street was untouched. Introduction In the last chapter we examined one of the major causes of poor reasoning, getting off track and not focusing on the issues related to a conclusion. In our general discussion of arguments (Chapters 1-3), however, we saw that arguments can be weak in two other ways: 1. In deductive reasoning, arguments can be valid, but have false or questionable premises, or in both deductive and inductive reasoning, arguments may involve language tricks that mislead us into presuming evidence is being offered in the premises when it is not. 2. In weak inductive arguments, arguments can have true and relevant premises but those premises can be insufficient to justify a conclusion as a reliable guide to the future. Fallacies that use deductive valid reasoning, but have premises that are questionable or are unfair in some sense in the truth claims they make, we will call fallacies of questionable premise. As a subset of fallacies of questionable premise, fallacies that use tricks in the way the premises are presented, such that there is a danger of presuming evidence has been offered when it has not, we will call fallacies of presumption. -

35. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Sexy Technical Communications Open Educational Resources 3-1-2016 35. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Cherie Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/oertechcomm Part of the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Steve and Miller, Cherie, "35. Logic: Common Fallacies" (2016). Sexy Technical Communications. 35. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/oertechcomm/35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sexy Technical Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve and Cherie Miller Sexy Technical Communication Home Logic and Logical Fallacies Taken with kind permission from the book Why Brilliant People Believe Nonsense by J. Steve Miller and Cherie K. Miller Brilliant People Believe Nonsense [because]... They Fall for Common Fallacies The dull mind, once arriving at an inference that flatters the desire, is rarely able to retain the impression that the notion from which the inference started was purely problematic. ― George Eliot, in Silas Marner In the last chapter we discussed passages where bright individuals with PhDs violated common fallacies. Even the brightest among us fall for them. As a result, we should be ever vigilant to keep our critical guard up, looking for fallacious reasoning in lectures, reading, viewing, and especially in our own writing. None of us are immune to falling for fallacies. -

Argument Content and Argument Source: an Exploration

Argument Content and Argument Source: An Exploration ULRIKE HAHN ADAM J.L. HARRIS ADAM CORNER School of Psychology Cardiff University Tower Building Park Place Cardiff CF10 3AT United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Argumentation is pervasive Résumé: L’argumentation est em- in everyday life. Understanding what ployée couramment dans la vie de tous makes a strong argument is therefore les jours. Il est donc dans notre intérêt of both theoretical and practical théorique et pratique de comprendre interest. One factor that seems ce qui rend un argument puissant. Un intuitively important to the strength of facteur qui semble intuitivement im- an argument is the reliability of the portant qui contribue à cette puissance source providing it. Whilst traditional est la fiabilité des sources d’infor- approaches to argument evaluation are mation employées dans un argument. silent on this issue, the Bayesian Quoique les approches traditionnelles approach to argumentation (Hahn & sur l’évaluation d’un argument soient Oaksford, 2007) is able to capture silencieuses sur ce sujet, l’approche important aspects of source reliability. bayesienne peut apporter quelques In particular, the Bayesian approach aspects importants sur l’évaluation de predicts that argument content and la fiabilité des sources: elle prédit que source reliability should interact to le contenu d’un argument et la fiabilité determine argument strength. In this d’une source devraient agir un sur paper, we outline the approach and l’autre pour déterminer la puissance then demonstrate the importance of d’un argument. Dans cet article nous source reliability in two empirical traçons les grandes lignes de cette studies. -

Naturalness and Unnaturalness in Contemporary Bioethics Anna Smajdor 57 Artikkel Samtale & Kritikk Spalter Brev

ARTIKKEL SAMTALE & KRITIKK SPALTER BREV Meta-ethical and methodological considerations The is/ought distinction and the naturalistic fallacy FRA FORSKNINGSFRONTEN Nature appears in bioethics in a number of guises and con- There is no great invention, from fire to flying, which has texts. At the most basic level, people may feel that it is mo- not been hailed as an insult to some god. But if every rally wrong to alter, distort or subvert natural processes. physical and chemical invention is a blasphemy, every NATURALNESS AND Leon Kass, for example, argues that an intuitive recoiling biological invention is a perversion. There is hardly one from interventions such as cloning that distort or frag- which, on first being brought to the notice of an observer ment the natural processes of reproduction, is a powerful from any nation which had not previously heard of their UNNATURALNESS IN indicator that such interventions are unethical (1998:3– existence, would not appear to him as indecent and un- 61). These are perhaps the most obvious occasions when natural. (Haldane 1924) nature plays an explicit role in informing moral reaso- CONTEMPORARY ning in bioethics. However, there are many other ways in Peter Singer and Deane Wells state categorically that “… which nature colours the concepts and themes employed there is no valid argument from ‘unnatural’ to ‘wrong’ in bioethical deliberation. For example, bioethicists may (2006:9-26). Similar views can be found in the work of BIOETHICS be concerned with the natural world, or nature, especially many bioethicists. A report on the ethics of grafting hu- in terms of our moral responsibility to the environment. -

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4 Jeremy Avigad, Robert Y. Lewis, and Floris van Doorn Sep 10, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Mathematical Proof ............................................ 1 1.2 Symbolic Logic .............................................. 2 1.3 Interactive Theorem Proving ....................................... 4 1.4 The Semantic Point of View ....................................... 5 1.5 Goals Summarized ............................................ 6 1.6 About this Textbook ........................................... 6 2 Propositional Logic 7 2.1 A Puzzle ................................................. 7 2.2 A Solution ................................................ 7 2.3 Rules of Inference ............................................ 8 2.4 The Language of Propositional Logic ................................... 15 2.5 Exercises ................................................. 16 3 Natural Deduction for Propositional Logic 17 3.1 Derivations in Natural Deduction ..................................... 17 3.2 Examples ................................................. 19 3.3 Forward and Backward Reasoning .................................... 20 3.4 Reasoning by Cases ............................................ 22 3.5 Some Logical Identities .......................................... 23 3.6 Exercises ................................................. 24 4 Propositional Logic in Lean 25 4.1 Expressions for Propositions and Proofs ................................. 25 4.2 More commands ............................................ -

The Role of Reasoning in Constructing a Persuasive Argument

The Role of Reasoning in Constructing a Persuasive Argument <http://www.orsinger.com/PDFFiles/constructing-a-persuasive-argument.pdf> [The pdf version of this document is web-enabled with linking endnotes] Richard R. Orsinger [email protected] http://www.orsinger.com McCurley, Orsinger, McCurley, Nelson & Downing, L.L.P. San Antonio Office: 1717 Tower Life Building San Antonio, Texas 78205 (210) 225-5567 http://www.orsinger.com and Dallas Office: 5950 Sherry Lane, Suite 800 Dallas, Texas 75225 (214) 273-2400 http://www.momnd.com State Bar of Texas 37th ANNUAL ADVANCED FAMILY LAW COURSE August 1-4, 2011 San Antonio CHAPTER 11 © 2011 Richard R. Orsinger All Rights Reserved The Role of Reasoning in Constructing a Persuasive Argument Chapter 11 Table of Contents I. THE IMPORTANCE OF PERSUASION.. 1 II. PERSUASION IN ARGUMENTATION.. 1 III. BACKGROUND.. 2 IV. USER’S GUIDE FOR THIS ARTICLE.. 2 V. ARISTOTLE’S THREE COMPONENTS OF A PERSUASIVE SPEECH.. 3 A. ETHOS.. 3 B. PATHOS.. 4 C. LOGOS.. 4 1. Syllogism.. 4 2. Implication.. 4 3. Enthymeme.. 4 (a) Advantages and Disadvantages of Commonplaces... 5 (b) Selection of Commonplaces.. 5 VI. ARGUMENT MODELS (OVERVIEW)... 5 A. LOGIC-BASED ARGUMENTS. 5 1. Deductive Logic.. 5 2. Inductive Logic.. 6 3. Reasoning by Analogy.. 7 B. DEFEASIBLE ARGUMENTS... 7 C. THE TOULMIN ARGUMENTATION MODEL... 7 D. FALLACIOUS ARGUMENTS.. 8 E. ARGUMENTATION SCHEMES.. 8 VII. LOGICAL REASONING (DETAILED ANALYSIS).. 8 A. DEDUCTIVE REASONING.. 8 1. The Categorical Syllogism... 8 a. Graphically Depicting the Simple Categorical Syllogism... 9 b. A Legal Dispute as a Simple Syllogism.. 9 c. -

Read in Full (PDF File)

THE HOLY GRAIL: IN PURSUIT OF THE DISSERTATION PROPOSAL Michael Watts Institute of International Studies University of California, Berkeley “[T]here is too little emphasis ... on what it means to do independent research” -William Bowen and Neil Rudenstein In Pursuit of the Ph.D. 1992 Introduction One of the great curiosities of academia is that the art of writing a research proposal–arguably one of the most difficult and demanding tasks confronting any research student–is so weakly institutionalized within graduate programs. The same, incidentally, might be said of fieldwork, whether the site is a village in northern Uganda or an archive in Pittsburgh. My experience is that fieldwork has all of the aura (and anxiety) of any rite of passage. But with a difference. It is a Darwinian learning-by- doing ordeal for which there is presumed to be no body of preparatory knowledge that can be passed on in advance; those that succeed return, and those that don’t are never seen again. It is perhaps for such reasons that Bowen and Rudenstein in their important book In Pursuit of the Ph.D. see the period between the end of coursework and the engagement of a dissertation topic as one of the most fraught and difficult in graduate formation. The selection of a topic they say is ‘a formidable task’, and students must be–but in practice rarely are in the social sciences and the humanities–encouraged to engage with their dissertation project in their first and second years. All of this is to say that the transition–another rite of passage–from course work to dissertation project is often paralyzing (“How exactly am I going to operationalize my crypto-Foucauldian study of the micro-physics of political power in San Francsico’s credit unions”?) and typically a source of bewilderment, anxiety and yes, even depression. -

The Naturalizing Error

Douglas Allchin & Alexander J. Werth The Naturalizing Error Douglas Allchin Minnesota Center for the Philosophy of Science University of Minnesota Minneapolis MN 55455 e-mail: [email protected] phone: 651.603.8805 Alexander J. Werth Department of Biology Hampden-Sydney College Hampden Sydney VA 23901 Abstract We describe an error type that we call the naturalizing error: an appeal to nature as a self-justified description dictating or limiting our choices in moral, economic, political, and other social contexts. Normative cultural perspectives may be subtly and subconsciously inscribed into purportedly objective descriptions of nature, often with the apparent warrant and authority of science, yet not be fully warranted by a systematic or complete consideration of the evidence. Cognitive processes may contribute further to a failure to notice the lapses in scientific reasoning and justificatory warrant. By articulating this error type at a general level, we hope to raise awareness of this pervasive error type and to facilitate critiques of claims that appeal to what is “natural” as inevitable or unchangeable. Keywords error types; naturalizing error; naturalistic fallacy; public understanding of science; social construction of science The Naturalizing Error Abstract We describe an error type that we call the naturalizing error: an appeal to nature as a self-justified description dictating or limiting our choices in moral, economic, political, and other social contexts. Normative cultural perspectives may be subtly and subconsciously inscribed into purportedly objective descriptions of nature, often with the apparent warrant and authority of science, yet not be fully warranted by a systematic or complete consideration of the evidence.