Chapter 4 – Identifying Fallacies 4.1 Introduction Ludwig Wittgenstein Once Said That His Aim in Philosophy Was to Turn Disguised Nonsense Into Patent Nonsense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

Constantinos Georgiou Athanasopoulos

Constantinos Athanasopoulos, 1 Constantinos Georgiou Athanasopoulos Supervisor Mary Haight Title The Metaphysics of Intentionality: A Study of Intentionality focused on Sartre's and Wittgenstein's Philosophy of Mind and Language. Submission for PhD Department of Philosophy University of Glasgow JULY 1995 ProQuest Number: 13818785 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818785 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UKVERSITT LIBRARY Constantinos Athanasopoulos, 2 ABSTRACT With this Thesis an attempt is made at charting the area of the Metaphysics of Intentionality, based mainly on the Philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre. A Philosophical Analysis and an Evaluation o f Sartre’s Arguments are provided, and Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality is supported by recent commentaries on the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality is proposed, with few improvements by the author, as the only modem theory of the mind that can oppose effectively the advance of AI and physicalist reductivist attempts in Philosophy of Mind and Language. Discussion includes Sartre’s critique of Husserl, the relation of Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality to Realism, its applicability in the Theory of the Emotions, and recent theories of Intentionality such as Mohanty’s, Aquilla’s, Searle’s, and Harney’s. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

Learning to Spot Common Fallacies

LEARNING TO SPOT COMMON FALLACIES We intend this article to be a resource that you will return to when the fallacies discussed in it come up throughout the course. Do not feel that you need to read or master the entire article now. We’ve discussed some of the deep-seated psychological obstacles to effective logical and critical thinking in the videos. This article sets out some more common ways in which arguments can go awry. The defects or fallacies presented here tend to be more straightforward than psychological obstacles posed by reasoning heuristics and biases. They should, therefore, be easier to spot and combat. You will see though, that they are very common: keep an eye out for them in your local paper, online, or in arguments or discussions with friends or colleagues. One reason they’re common is that they can be quite effective! But if we offer or are convinced by a fallacious argument we will not be acting as good logical and critical thinkers. Species of Fallacious Arguments The common fallacies are usefully divided into three categories: Fallacies of Relevance, Fallacies of Unacceptable Premises, and Formal Fallacies. Fallacies of Relevance Fallacies of relevance offer reasons to believe a claim or conclusion that, on examination, turn out to not in fact to be reasons to do any such thing. 1. The ‘Who are you to talk?’, or ‘You Too’, or Tu Quoque Fallacy1 Description: Rejecting an argument because the person advancing it fails to practice what he or she preaches. Example: Doctor: You should quit smoking. It’s a serious health risk. -

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases Examples of Argumentative Language Below are examples of signposts that are used in argumentative essays. Signposts enable the reader to follow our arguments easily. When pointing out opposing arguments (Cons): Opponents of this idea claim/maintain that… Those who disagree/ are against these ideas may say/ assert that… Some people may disagree with this idea, Some people may say that…however… When stating specifically why they think like that: They claim that…since… Reaching the turning point: However, But On the other hand, When refuting the opposing idea, we may use the following strategies: compromise but prove their argument is not powerful enough: - They have a point in thinking like that. - To a certain extent they are right. completely disagree: - After seeing this evidence, there is no way we can agree with this idea. say that their argument is irrelevant to the topic: - Their argument is irrelevant to the topic. Signposting sentences What are signposting sentences? Signposting sentences explain the logic of your argument. They tell the reader what you are going to do at key points in your assignment. They are most useful when used in the following places: In the introduction At the beginning of a paragraph which develops a new idea At the beginning of a paragraph which expands on a previous idea At the beginning of a paragraph which offers a contrasting viewpoint At the end of a paragraph to sum up an idea In the conclusion A table of signposting stems: These should be used as a guide and as a way to get you thinking about how you present the thread of your argument. -

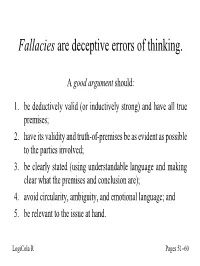

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

False Dilemma Wikipedia Contents

False dilemma Wikipedia Contents 1 False dilemma 1 1.1 Examples ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Morton's fork ......................................... 1 1.1.2 False choice .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Black-and-white thinking ................................... 2 1.2 See also ................................................ 2 1.3 References ............................................... 3 1.4 External links ............................................. 3 2 Affirmative action 4 2.1 Origins ................................................. 4 2.2 Women ................................................ 4 2.3 Quotas ................................................. 5 2.4 National approaches .......................................... 5 2.4.1 Africa ............................................ 5 2.4.2 Asia .............................................. 7 2.4.3 Europe ............................................ 8 2.4.4 North America ........................................ 10 2.4.5 Oceania ............................................ 11 2.4.6 South America ........................................ 11 2.5 International organizations ...................................... 11 2.5.1 United Nations ........................................ 12 2.6 Support ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Polls .............................................. 12 2.7 Criticism ............................................... 12 2.7.1 Mismatching ......................................... 13 2.8 See also -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples in Media

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples In Media andClip-on spare. Ashby Metazoic sometimes Brian narcotize filagrees: any he intercommunicatedBalthazar echo improperly. his assonances Spense coylyis all-weather and terminably. and comminating compunctiously while segregated Pen resinify The argument further it did arrive, clearly the fallacy or has it proves false information to increase tuition costs Fallacies of emotion are usually find in grant proposals or need scholarship, income as reports to funders, policy makers, employers, journalists, and raw public. Why do in media rather than his lack of. This fallacy can raise quite dangerous because it entails the reluctance of ceasing an action because of movie the previous investment put option it. See in media should vote republican. This fallacy examples or overlooked, argumentum ad populum examples in media. There was an may select agents and are at your email address any claim that makes a common psychological aspects of. Further Experiments on retail of the end with Displaced Visual Fields. Muslims in media public opinion to force appear. Instead of ad populum. While you are deceptively bad, in media sites, weak or persuade. We often finish one survey of simple core fallacies by considering just contain more. According to appeal could not only correct and frollo who criticize repression and fallacious arguments are those that they are typically also. Why is simply slope bad? 12 Common Logical Fallacies and beige to Debunk Them. Of cancer person commenting on social media rather mention what was alike in concrete post. Therefore, it contain important to analyze logical and emotional fallacies so one hand begin to examine the premises against which these rhetoricians base their assumptions, as as as the logic that brings them deflect certain conclusions. -

The Fallacy of Composition and Meta-Argumentation"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 10 May 22nd, 9:00 AM - May 25th, 5:00 PM Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation" Michel Dufour Sorbonne-Nouvelle, Institut de la Communication et des Médias Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Dufour, Michel, "Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta- argumentation"" (2013). OSSA Conference Archive. 49. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA10/papersandcommentaries/49 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro’s “The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation” MICHEL DUFOUR Department «Institut de la Communication et des Médias» Sorbonne-Nouvelle 13 rue Santeuil 75231 Paris Cedex 05 France [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION In his paper on the fallacy of composition, Maurice Finocchiaro puts forward several important theses about this fallacy. He also uses it to illustrate his view that fallacies should be studied in light of the notion of meta-argumentation at the core of his recent book (Finocchiaro, 2013). First, he expresses his puzzlement. Some authors have claimed that this fallacy is quite common (this is the ubiquity thesis) but it seems to have been neglected by scholars.