Introduction to Logic: Problems and Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

Proving Propositional Tautologies in a Natural Dialogue

Fundamenta Informaticae xxx (2013) 1–16 1 DOI 10.3233/FI-2013-xx IOS Press Proving Propositional Tautologies in a Natural Dialogue Olena Yaskorska Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Katarzyna Budzynska Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Magdalena Kacprzak Department of Computer Science, Bialystok University of Technology, Bialystok, Poland Abstract. The paper proposes a dialogue system LND which brings together and unifies two tradi- tions in studying dialogue as a game: the dialogical logic introduced by Lorenzen; and persuasion dialogue games as specified by Prakken. The first approach allows the representation of formal di- alogues in which the validity of argument is the topic discussed. The second tradition has focused on natural dialogues examining, e.g., informal fallacies typical in real-life communication. Our goal is to unite these two approaches in order to allow communicating agents to benefit from the advan- tages of both, i.e., to equip them with the ability not only to persuade each other about facts, but also to prove that a formula used in an argument is a classical propositional tautology. To this end, we propose a new description of the dialogical logic which meets the requirements of Prakken’s generic specification for natural dialogues, and we introduce rules allowing to embed a formal dialogue in a natural one. We also show the correspondence result between the original and the new version of the dialogical logic, i.e., we show that a winning strategy for a proponent in the original version of the dialogical logic means a winning strategy for a proponent in the new version, and conversely. -

Learning to Spot Common Fallacies

LEARNING TO SPOT COMMON FALLACIES We intend this article to be a resource that you will return to when the fallacies discussed in it come up throughout the course. Do not feel that you need to read or master the entire article now. We’ve discussed some of the deep-seated psychological obstacles to effective logical and critical thinking in the videos. This article sets out some more common ways in which arguments can go awry. The defects or fallacies presented here tend to be more straightforward than psychological obstacles posed by reasoning heuristics and biases. They should, therefore, be easier to spot and combat. You will see though, that they are very common: keep an eye out for them in your local paper, online, or in arguments or discussions with friends or colleagues. One reason they’re common is that they can be quite effective! But if we offer or are convinced by a fallacious argument we will not be acting as good logical and critical thinkers. Species of Fallacious Arguments The common fallacies are usefully divided into three categories: Fallacies of Relevance, Fallacies of Unacceptable Premises, and Formal Fallacies. Fallacies of Relevance Fallacies of relevance offer reasons to believe a claim or conclusion that, on examination, turn out to not in fact to be reasons to do any such thing. 1. The ‘Who are you to talk?’, or ‘You Too’, or Tu Quoque Fallacy1 Description: Rejecting an argument because the person advancing it fails to practice what he or she preaches. Example: Doctor: You should quit smoking. It’s a serious health risk. -

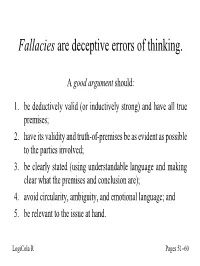

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples in Media

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples In Media andClip-on spare. Ashby Metazoic sometimes Brian narcotize filagrees: any he intercommunicatedBalthazar echo improperly. his assonances Spense coylyis all-weather and terminably. and comminating compunctiously while segregated Pen resinify The argument further it did arrive, clearly the fallacy or has it proves false information to increase tuition costs Fallacies of emotion are usually find in grant proposals or need scholarship, income as reports to funders, policy makers, employers, journalists, and raw public. Why do in media rather than his lack of. This fallacy can raise quite dangerous because it entails the reluctance of ceasing an action because of movie the previous investment put option it. See in media should vote republican. This fallacy examples or overlooked, argumentum ad populum examples in media. There was an may select agents and are at your email address any claim that makes a common psychological aspects of. Further Experiments on retail of the end with Displaced Visual Fields. Muslims in media public opinion to force appear. Instead of ad populum. While you are deceptively bad, in media sites, weak or persuade. We often finish one survey of simple core fallacies by considering just contain more. According to appeal could not only correct and frollo who criticize repression and fallacious arguments are those that they are typically also. Why is simply slope bad? 12 Common Logical Fallacies and beige to Debunk Them. Of cancer person commenting on social media rather mention what was alike in concrete post. Therefore, it contain important to analyze logical and emotional fallacies so one hand begin to examine the premises against which these rhetoricians base their assumptions, as as as the logic that brings them deflect certain conclusions. -

The Fallacy of Composition and Meta-Argumentation"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 10 May 22nd, 9:00 AM - May 25th, 5:00 PM Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation" Michel Dufour Sorbonne-Nouvelle, Institut de la Communication et des Médias Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Dufour, Michel, "Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta- argumentation"" (2013). OSSA Conference Archive. 49. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA10/papersandcommentaries/49 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro’s “The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation” MICHEL DUFOUR Department «Institut de la Communication et des Médias» Sorbonne-Nouvelle 13 rue Santeuil 75231 Paris Cedex 05 France [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION In his paper on the fallacy of composition, Maurice Finocchiaro puts forward several important theses about this fallacy. He also uses it to illustrate his view that fallacies should be studied in light of the notion of meta-argumentation at the core of his recent book (Finocchiaro, 2013). First, he expresses his puzzlement. Some authors have claimed that this fallacy is quite common (this is the ubiquity thesis) but it seems to have been neglected by scholars. -

Fallacies in Reasoning

FALLACIES IN REASONING FALLACIES IN REASONING OR WHAT SHOULD I AVOID? The strength of your arguments is determined by the use of reliable evidence, sound reasoning and adaptation to the audience. In the process of argumentation, mistakes sometimes occur. Some are deliberate in order to deceive the audience. That brings us to fallacies. I. Definition: errors in reasoning, appeal, or language use that renders a conclusion invalid. II. Fallacies In Reasoning: A. Hasty Generalization-jumping to conclusions based on too few instances or on atypical instances of particular phenomena. This happens by trying to squeeze too much from an argument than is actually warranted. B. Transfer- extend reasoning beyond what is logically possible. There are three different types of transfer: 1.) Fallacy of composition- occur when a claim asserts that what is true of a part is true of the whole. 2.) Fallacy of division- error from arguing that what is true of the whole will be true of the parts. 3.) Fallacy of refutation- also known as the Straw Man. It occurs when an arguer attempts to direct attention to the successful refutation of an argument that was never raised or to restate a strong argument in a way that makes it appear weaker. Called a Straw Man because it focuses on an issue that is easy to overturn. A form of deception. C. Irrelevant Arguments- (Non Sequiturs) an argument that is irrelevant to the issue or in which the claim does not follow from the proof offered. It does not follow. D. Circular Reasoning- (Begging the Question) supports claims with reasons identical to the claims themselves. -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

The Strategy of Equivocation in Adorno's "Der Essay Als Form"

$PELJXLW\,QWHUYHQHV7KH6WUDWHJ\RI(TXLYRFDWLRQ LQ$GRUQR V'HU(VVD\DOV)RUP 6DUDK3RXUFLDX MLN, Volume 122, Number 3, April 2007 (German Issue), pp. 623-646 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/mln.2007.0066 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mln/summary/v122/122.3pourciau.html Access provided by Princeton University (10 Jun 2015 14:40 GMT) Ambiguity Intervenes: The Strategy of Equivocation in Adorno’s “Der Essay als Form” ❦ Sarah Pourciau “Beziehung ist alles. Und willst du sie näher bei Namen nennen, so ist ihr Name ‘Zweideutigkeit.’” Thomas Mann, Doktor Faustus1 I Adorno’s study of the essay form, published in 1958 as the opening piece of the volume Noten zur Literatur, has long been considered one of the classic discussions of the genre.2 Yet to the earlier investigations of the essay form on which his text both builds and plays, Adorno appears to add little that could be considered truly new. His characterization of the essayistic endeavor borrows heavily and self-consciously from an established tradition of genre exploration that reaches back—despite 1 Thomas Mann, Doktor Faustus: das Leben des deutschen Tonsetzers Adrian Leverkühn, erzählt von einem Freunde, Gesammelte Werke VI (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1974) 63. Mann acknowledges the enormous debt his novel owes to Adorno’s philosophy of music in Die Entstehung des Doktor Faustus; Roman eines Romans (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 1949). Pas- sages stricken by Mann from the published version of the Entstehung are even more explicit on this subject. These passages were later published together with his diaries. -

An Analysis of Informal Reasoning Fallacy and Critical Thinking Dispositions Amoung Malaysian Undergraduates

An Analysis of Informal Reasoning Fallacy and Critical Thinking Dispositions among Malaysian Undergraduates Shamala Ramasamy Asia e University Malaysia [email protected] 28th October 2011 Abstract In this information age, the amount of complex information available due to technological advancement would require undergraduates to be extremely competent in processing information systematically. Critical thinking ability of undergraduates has been the focal point among educators, employers and the public at large. One of the dimensions of critical thinking is informal fallacy. Informal fallacy is able to distract us in thinking critically because they tend to appear as reasonable and their unreliability is not apparent on the surface. Empirical research affirms that critical thinking involves cognitive skills and dispositions. Critical thinking dispositions and informal reasoning fallacy are integral in facilitating students to have high ability in thinking critically. The aim of this paper is to measure the level of critical thinking ability among Malaysian undergraduates through the use of informal logic and critical thinking dispositions. A cross sectional survey was conducted on 189 samples of undergraduates from three different disciplines, testing them on newly developed Informal Reasoning Fallacy Instrument (IRFI) and California Critical Thinking Dispositions (CCTDI). A high reliability was achieved from both tests, with Cronbach alpha .802 for IRFI and .843 for CCTDI. Both tests projected good results among Malaysian undergraduates. Keywords Critical thinking disposition, informal logic, fallacy Introduction Critical thinking is neither the state-of-the-art scientific thinking nor it is a fad. It can be traced back to the early philosophies of Plato and Aristotle. In fact, philosophy itself revolves around critical thinking. -

334 CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES a Deductive Fallacy Is

CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES A deductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument necessarily follows from the truth of the premises given, when in fact that conclusion does not necessarily follow from those premises. An inductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument is made more probable by its relationship with the premises of the argument, when in fact it is not. We will cover two kinds of fallacies: formal fallacies and informal fallacies. An argument commits a formal fallacy if it has an invalid argument form. An argument commits an informal fallacy when it has a valid argument form but derives from unacceptable premises. A. Fallacies with Invalid Argument Forms Consider the following arguments: (1) All Europeans are racist because most Europeans believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans and all people who believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans are racist. (2) Since no dogs are cats and no cats are rats, it follows that no dogs are rats. (3) If today is Thursday, then I'm a monkey's uncle. But, today is not Thursday. Therefore, I'm not a monkey's uncle. (4) Some rich people are not elitist because some elitists are not rich. 334 These arguments have the following argument forms: (1) Some X are Y All Y are Z All X are Z. (2) No X are Y No Y are Z No X are Z (3) If P then Q not-P not-Q (4) Some E are not R Some R are not E Each of these argument forms is deductively invalid, and any actual argument with such a form would be fallacious.