Critical Reasoning and Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

Beardsley's Theory of Analogy

INFORMAL LOGIC XI.3, Fall 1989 Beardsley's Theory of Analogy EVELYN M. BARKER The University of Maryland 1. Is the Argument from Analogy a consequences of an "abdication of Fallacy? statesmanship."2 Kissinger cites historical analogy as the only basis for sound judg In the various editions of Practical Logic ment in international diplomacy: and Thinking Straight Monroe Beardsley History is the only experience on which pioneered informal logic, the assessment of statesmen can draw. But it does not teach reasoning techniques employed in actual its lessons automatically. It demonstrates the human situations. 1 Although acknowledg consequences of comparable situations, but ing the prominence of analogies in reason each generation has to determine what situa ing, he contended that analogy has some tions are in fact comparable. heuristic uses, but an argument based on one Such analogical arguments, as Kissinger is inherently fallacious: points out, are directed to finding suitable Analogies illustrate, and they lead to premises for wise and prudent action. hypotheses, but thinking in terms of analogy Beardsley's intellectualist approach limits becomes fallacious when the analogy is us rational argumentation to asserting premises ed as a reason for a principle. This fallacy as evidence for the truth of a conclusion. is called the "argument from analogy." Consequently he overlooks or misconceives (PL 107) the character of some forms of analogical Beardsley's view implies that no serious argument prevalent in practical reasoning. reasoner will use analogies between things It is misleading to speak of "the argument in drawing conclusions, or be persuaded by from analogy," as Beardsley does, as if all another's introduction of them. -

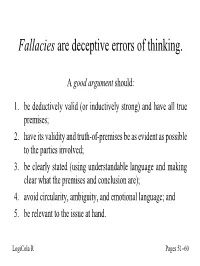

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

False Dilemma Wikipedia Contents

False dilemma Wikipedia Contents 1 False dilemma 1 1.1 Examples ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Morton's fork ......................................... 1 1.1.2 False choice .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Black-and-white thinking ................................... 2 1.2 See also ................................................ 2 1.3 References ............................................... 3 1.4 External links ............................................. 3 2 Affirmative action 4 2.1 Origins ................................................. 4 2.2 Women ................................................ 4 2.3 Quotas ................................................. 5 2.4 National approaches .......................................... 5 2.4.1 Africa ............................................ 5 2.4.2 Asia .............................................. 7 2.4.3 Europe ............................................ 8 2.4.4 North America ........................................ 10 2.4.5 Oceania ............................................ 11 2.4.6 South America ........................................ 11 2.5 International organizations ...................................... 11 2.5.1 United Nations ........................................ 12 2.6 Support ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Polls .............................................. 12 2.7 Criticism ............................................... 12 2.7.1 Mismatching ......................................... 13 2.8 See also -

Logic and Contemporary Rhetoric

How happy are the astrologers, who are It ain’t so much the things we don’t believed if they tell one truth to a know that get us into trouble. It’s the hundred lies, while other people lose all things we know that ain’t so. credit if they tell one lie to a hundred —Artemus Ward truths. —Francesco Guicciardini Chapter 4 FALLACIOUS REASONING—2 Most instances of the fallacies discussed in the previous chapter fall into the broad fallacy categories questionable premise or suppressed evidence. Most of the fallacies to be discussed in this and the next chapter belong to the genus invalid inference. 1. AD HOMINEM ARGUMENT There is a famous and perhaps apocryphal story lawyers like to tell that nicely captures the flavor of this fallacy. In Great Britain, the practice of law is divided between solici- tors, who prepare cases for trial, and barristers, who argue the cases in court. The story concerns a particular barrister who, depending on the solicitor to prepare his case, arrived in court with no prior knowledge of the case he was to plead, where he found an exceedingly thin brief, which when opened contained just one note: “No case; abuse the plaintiff’s attorney.” If the barrister did as instructed, he was guilty of arguing ad hominem—of attacking his opponent rather than his opponent’s evidence and argu- ments. (An ad hominem argument, literally, is an argument “to the person.”) Both liberals and conservatives are the butt of this fallacy much too often. Not long after Barack Obama was elected to the Senate, Rush Limbaugh repeatedly referred to him as “Obama Osama” when criticizing the senator and the Democrats in general. -

The Critical Thinking Toolkit

Galen A. Foresman, Peter S. Fosl, and Jamie Carlin Watson The CRITICAL THINKING The THE CRITICAL THINKING TOOLKIT GALEN A. FORESMAN, PETER S. FOSL, AND JAMIE C. WATSON THE CRITICAL THINKING TOOLKIT This edition first published 2017 © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Galen A. Foresman, Peter S. Fosl, and Jamie C. Watson to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

The Argument Form “Appeal to Galileo”: a Critical Appreciation of Doury's Account

The Argument Form “Appeal to Galileo”: A Critical Appreciation of Doury’s Account MAURICE A. FINOCCHIARO Department of Philosophy University of Nevada, Las Vegas Las Vegas, NV 89154-5028 USA [email protected] Abstract: Following a linguistic- Résumé: En poursuivant une ap- descriptivist approach, Marianne proche linguistique-descriptiviste, Doury has studied debates about Marianne Doury a étudié les débats “parasciences” (e.g. astrology), dis- sur les «parasciences » (par exem- covering that “parascientists” fre- ple, l'astrologie), et a découvert que quently argue by “appeal to Galileo” les «parasavants» raisonnent souvent (i.e., defend their views by compar- en faisant un «appel à Galilée" (c.-à- ing themselves to Galileo and their d. ils défendent leurs points de vue opponents to the Inquisition); oppo- en se comparant à Galileo et en nents object by criticizing the analo- comparant leurs adversaires aux gy, charging fallacy, and appealing juges de l’Inquisition). Les adver- to counter-examples. I argue that saires des parasavant critiquent Galilean appeals are much more l'analogie en la qualifiant de soph- widely used, by creationists, global- isme, et en construisant des contre- warming skeptics, advocates of “set- exemples. Je soutiens que les appels tled science”, great scientists, and à Galilée sont beaucoup plus large- great philosophers. Moreover, sever- ment utilisés, par des créationnistes, al subtypes should be distinguished; des sceptiques du réchauffement critiques questioning the analogy are planétaire, des défenseurs de la «sci- proper; fallacy charges are problem- ence établie», des grands scien- atic; and appeals to counter- tifiques, et des grands philosophes. examples are really indirect critiques En outre, on doit distinguer plusieurs of the analogy. -

Circles and Analogies in Public Health Reasoning Louise Cummings

SUMMER 2014, VOL. 29, NO. 2 35 Circles and Analogies in Public Health Reasoning Louise Cummings School of Arts and Humanities Nottingham Trent University, UK Abstract 7KHVWXG\RIWKHIDOODFLHVKDVFKDQJHGDOPRVWEH\RQGUHFRJQLWLRQVLQFH&KDUOHV+DPEOLQFDOOHG IRUDUDGLFDOUHDSSUDLVDORIWKLVDUHDRIORJLFDOLQTXLU\LQKLVERRN)DOODFLHV7KH³ZLWOHVV H[DPSOHVRIKLVIRUEHDUV´WRZKLFK+DPEOLQUHIHUUHGKDYHODUJHO\EHHQUHSODFHGE\PRUH authentic cases of the fallacies in actual use. It is now not unusual for fallacy and argumentation theorists to draw on actual sources for examples of how the fallacies are used in our everyday UHDVRQLQJ+RZHYHUDQDVSHFWRIWKLVPRYHWRZDUGVJUHDWHUDXWKHQWLFLW\LQWKHVWXG\RIWKH fallacies, an aspect which has been almost universally neglected, is the attempt to subject the fallacies to empirical testing of the type which is more commonly associated with psychological experiments on reasoning. This paper addresses this omission in research on the fallacies by examining how subjects use two fallacies – circular argument and analogical argument – during a reasoning task in which subjects are required to consider a number of public health scenarios. Results are discussed in relation to a view of the fallacies as cognitive heuristics that facilitate reasoning in a context of uncertainty. Keywords: analogical argument, circular argument, heuristic, informal fallacy, public health, reasoning, uncertainty I. Introduction puns, anecdotes, and witless examples of his forbears. The study of the fallacies has changed :KHUHSKLORVRSKLFDOUHÀHFWLRQRQWKH considerably in -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

Logical Fallacies and Distraction Techniques

Sample Activity Learning Critical Thinking Through Astronomy: Logical Fallacies and Distraction Techniques Joe Heafner [email protected] Version 2017-09-13 STUDENT NOTE PLEASE DO NOT DISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT. 2017-09-13 Activity0105 CONTENTS Contents QuestionsSample Activity1 Materials Needed 1 Points To Remember 1 1 Fallacies and Distractions1 Student1.1 Lying................................................. Version 1 1.2 Shifting The Burden.........................................2 1.3 Appeal To Emotion.........................................3 1.4 Appeal To The Past.........................................4 1.5 Appeal To Novelty..........................................5 1.6 Appeal To The People (Appeal To The Masses, Appeal To Popularity).............6 1.7 Appeal To Logic...........................................7 1.8 Appeal To Ignorance.........................................8 1.9 Argument By Repetition....................................... 10 1.10 Attacking The Person........................................ 11 1.11 Confirmation Bias.......................................... 12 1.12 Strawman Argument or Changing The Subject.......................... 13 1.13 False Premise............................................. 14 1.14 Hasty Generalization......................................... 15 1.15 Loaded Question........................................... 16 1.16 Feigning Offense........................................... 17 1.17 False Dilemma............................................ 17 1.18 Appeal To Authority........................................