Valuation of Scleroderma and Psoriatic Arthritis Health States by the General Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of the Evidence for and Against a Role for Mast Cells in Cutaneous Scarring and Fibrosis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review A Review of the Evidence for and against a Role for Mast Cells in Cutaneous Scarring and Fibrosis Traci A. Wilgus 1,*, Sara Ud-Din 2 and Ardeshir Bayat 2,3 1 Department of Pathology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 2 Centre for Dermatology Research, NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Research, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PT, UK; [email protected] (S.U.-D.); [email protected] (A.B.) 3 MRC-SA Wound Healing Unit, Division of Dermatology, University of Cape Town, Observatory, Cape Town 7945, South Africa * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-614-366-8526 Received: 1 October 2020; Accepted: 12 December 2020; Published: 18 December 2020 Abstract: Scars are generated in mature skin as a result of the normal repair process, but the replacement of normal tissue with scar tissue can lead to biomechanical and functional deficiencies in the skin as well as psychological and social issues for patients that negatively affect quality of life. Abnormal scars, such as hypertrophic scars and keloids, and cutaneous fibrosis that develops in diseases such as systemic sclerosis and graft-versus-host disease can be even more challenging for patients. There is a large body of literature suggesting that inflammation promotes the deposition of scar tissue by fibroblasts. Mast cells represent one inflammatory cell type in particular that has been implicated in skin scarring and fibrosis. Most published studies in this area support a pro-fibrotic role for mast cells in the skin, as many mast cell-derived mediators stimulate fibroblast activity and studies generally indicate higher numbers of mast cells and/or mast cell activation in scars and fibrotic skin. -

Foot Pain in Scleroderma

Foot Pain in Scleroderma Dr Begonya Alcacer-Pitarch LMBRU Postdoctoral Research Fellow 20th Anniversary Scleroderma Family Day 16th May 2015 Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Presentation Content n Introduction n Different types of foot pain n Factors contributing to foot pain n Impact of foot pain on Quality of Life (QoL) Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Scleroderma n Clinical features of scleroderma – Microvascular (small vessel) and macrovascular (large vessel) damage – Fibrosis of the skin and internal organs – Dysfunction of the immune system n Unknown aetiology n Female to male ratio 4.6 : 1 n The prevalence of SSc in the UK is 8.21 per 100 000 Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Foot Involvement in SSc n Clinically 90% of SSc patients have foot involvement n It typically has a later involvement than hands n Foot involvement is less frequent than hand involvement, but is potentially disabling Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Different Types of Foot Pain Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Ischaemic Pain (vascular) Microvascular disease (small vessel) n Intermittent pain – Raynaud’s (spasm) • Cold • Throb • Numb • Tingle • Pain n Constant pain – Vessel center narrows • Distal pain (toes) • Gradually increasing pain • Intolerable pain when necrosis is present Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Ischaemic Pain (vascular) Macrovascular disease (large vessels) n Intermittent and constant pain – Peripheral Arterial Disease • Intermittent claudication – Muscle pain (ache, cramp) during walking • Aching or burning pain • Night and rest pain • Cramps Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Ulcer Pain n Ulcer development – Constant pain n Infected ulcer – Unexpected/ excess pain or tenderness Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Neuropathic Pain n Nerve damage is not always obvious. -

Nodular Morphea

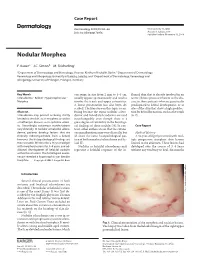

Case Report Dermatology 2009;218:63–66 Received: July 13, 2008 DOI: 10.1159/000173976 Accepted: July 23, 2008 Published online: November 13, 2008 Nodular Morphea a b c F. Kauer J.C. Simon M. Sticherling a b Department of Dermatology and Venerology, Vivantes Klinikum Neukölln, Berlin , Department of Dermatology, c Venerology and Allergology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig , and Department of Dermatology, Venerology and Allergology, University of Erlangen, Erlangen , Germany Key Words can range in size from 2 mm to 4–5 cm, flamed skin that is already involved in an -Scleroderma ؒ Keloid ؒ Hypertrophic scar ؒ usually appear spontaneously and tend to active fibrotic process inherent to the dis Morphea involve the trunk and upper extremities. ease in those patients who are genetically A linear presentation has also been de- predisposed to keloid development, or at scribed. The literature on this topic is con- sites of the skin that show a high predilec- Abstract fusing because the terms ‘nodular sclero- tion for keloid formation, such as the trunk Scleroderma may present as being strictly derma’ and ‘keloidal scleroderma’ are used [6, 7] . limited to the skin, as in morphea, or within interchangeably even though there is a a multiorgan disease, as in systemic sclero- great degree of variability in the histologi- sis. Accordingly, cutaneous manifestations cal findings of these nodules [4] . In con- C a s e R e p o r t vary clinically. In nodular or keloidal sclero- trast, other authors stress that the cutane- derma, patients develop lesions that are ous manifestations may vary clinically, but Medical History clinically indistinguishable from a keloid; all share the same histopathological pat- A 16-year-old girl presented with mul- however, the histopathological findings are tern of both morphea/scleroderma and ke- tiple progressive morpheic skin lesions more variable. -

Topical Photodynamic Therapy for Localized Scleroderma

Acta Derm Venereol 2000; 80: 26±27 Topical Photodynamic Therapy for Localized Scleroderma SIGRID KARRER, CHRISTOPH ABELS, MICHAEL LANDTHALER and ROLF-MARKUS SZEIMIES Department of Dermatology, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany Therapy of localized scleroderma is unsatisfactory, with MATERIAL AND METHODS numerous treatments being used that have only limited success Patients or considerable side-effects. The aim of this trial was to determine whether topical photodynamic therapy would be Five patients aged between 21 and 63 years with biopsy-proven effective in patients with localized scleroderma. Five patients localized scleroderma (morphoea) were studied. All patients had evidence of progressive disease, i.e. lesions showed an in¯ammatory with progressive disease, in whom conventional therapies had reaction and increase in size. In each patient the condition had failed, were treated by application of a gel containing 3% previously failed to respond to potent topical corticosteroids, systemic 5-aminolevulinic acid followed by irradiation with an incoherent therapy with penicillin and/or PUVA bath photochemotherapy. lamp (40 mW/cm2, 10 J/cm2). The treatment was performed Patients were required to discontinue all therapy at least 4 weeks once or twice weekly for 3 ± 6 months. In all patients the before study initiation. The most affected sclerotic plaque of each therapy was highly effective for sclerotic plaques, as measured patient was judged at baseline and then every 2 weeks during by a quantitative durometer score and a clinical skin score. The treatment. Sclerotic plaques were assessed by a clinical skin score (10) only side-effect was a transient hyperpigmentation of the and the durometer score (11). -

Oral Health Care for Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa

Oral Health Care for Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa Best Clinical Practice Guidelines October 2011 Oral Health Care for Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa Best Clinical Practice Guidelines October 2011 Clinical Editor: Susanne Krämer S. Methodological Editor: Julio Villanueva M. Authors: Prof. Dr. Susanne Krämer Dr. María Concepción Serrano Prof. Dr. Gisela Zillmann Dr. Pablo Gálvez Prof. Dr. Julio Villanueva Dr. Ignacio Araya Dr. Romina Brignardello-Petersen Dr. Alonso Carrasco-Labra Prof. Dr. Marco Cornejo Mr. Patricio Oliva Dr. Nicolás Yanine Patient representatives: Mr. John Dart Mr. Scott O’Sullivan Pilot: Dr. Victoria Clark Dr. Gabriela Scagnet Dr. Mariana Armada Dr. Adela Stepanska Dr. Renata Gaillyova Dr. Sylvia Stepanska Review: Prof. Dr. Tim Wright Dr. Marie Callen Dr. Carol Mason Prof. Dr. Stephen Porter Dr. Nina Skogedal Dr. Kari Storhaug Dr. Reinhard Schilke Dr. Anne W Lucky Ms. Lesley Haynes Ms. Lynne Hubbard Mr. Christian Fingerhuth Graphic design: Ms. Isabel López Production: Gráfica Metropolitana Funding: DEBRA UK © DEBRA International This work is subject to copyright. ISBN-978-956-9108-00-6 Versión On line: ISBN 978-956-9108-01-3 Printed in Chile in October 2011 Editorial: DEBRA Chile Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Coni V., María Elena, María José, Daniela, Annays, Lisette, Victor, Coni S., Esteban, Coni A., Felipe, Nibaldo, María, Cristián, Deyanira and Victoria for sharing their smile to make these Guidelines more friendly. 4 Contents 1 Introduction 07 2 Oral care for patients with Inherited Epidermolysis Bullosa 11 3 Dental treatment 19 4 Anaesthetic management 29 5 Summary of recommendations 33 Development of the guideline 37 6 Appendix 43 7.1 List of abbreviations and glossary 7.2 Oral manifestations of Epidermolysis Bullosa 7 7.3 General information on Epidermolysis Bullosa 7.4 Exercises for mouth, jaw and tongue 8 References 61 5 A message from the patient representative: “Be guided by the professionals. -

Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) — Adult Conditions for Which Ivig Has an Established Therapeutic Role

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) — adult Conditions for which IVIg has an established therapeutic role. Specific Conditions Newly Diagnosed Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Persistent Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Chronic Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Evans syndrome ‐ with significant Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) ‐ adult Indication for IVIg Use Newly diagnosed ITP — initial Ig therapy ITP in pregnancy — initial Ig therapy ITP with life‐threatening haemorrhage or the potential for life‐threatening haemorrhage Newly diagnosed or persistent ITP — subsequent therapy (diagnosis <12 months) Refractory persistent or chronic ITP — splenectomy failed or contraindicated and second‐line agent unsuccessful Subsequent or ongoing treatment for ITP responders during pregnancy and the postpartum period ITP and inadequate platelet count for planned surgery HIV‐associated ITP Level of Evidence Evidence of probable benefit – more research needed (Category 2a) Description and Diagnostic Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is a reduction in platelet count Criteria (thrombocytopenia) resulting from shortened platelet survival due to anti‐platelet antibodies, reduced platelet production due to immune induced reduced megakaryopoeisis and/or immune mediated direct platelet lysis. When counts are very low (less than 30x109/L), bleeding into the skin (purpura) and mucous membranes can occur. Bone marrow platelet production (megakaryopoiesis) is morphologically normal. In some cases, there is additional impairment of platelet function related to antibody binding to glycoproteins on the platelet surface. It is a common finding in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, and while it may be found at any stage of the infection, its prevalence increases as HIV disease advances. Around 80 percent of adults with ITP have the chronic form of disease. -

Systemic Sclerosis/Scleroderma: a Treatable Multisystem Disease

Systemic Sclerosis/Scleroderma: A Treatable Multisystem Disease MONIQUE HINCHCLIFF, MD, and JOHN VARGA, MD Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois Systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) is a chronic connective tissue disease of unknown etiology that causes wide- spread microvascular damage and excessive deposition of collagen in the skin and internal organs. Raynaud phenome- non and scleroderma (hardening of the skin) are hallmarks of the disease. The typical patient is a young or middle-age woman with a history of Raynaud phenomenon who presents with skin induration and internal organ dysfunction. Clinical evaluation and laboratory testing, along with pulmonary function testing, Doppler echocardiography, and high-resolution computed tomography of the chest, establish the diagnosis and detect visceral involvement. Patients with systemic sclerosis can be classified into two distinct clinical subsets with different patterns of skin and internal organ involvement, autoantibody production, and survival. Prognosis is determined by the degree of internal organ involvement. Although no disease-modifying therapy has been proven effective, complications of systemic sclerosis are treatable, and interventions for organ-specific manifestations have improved substantially. Medications (e.g., cal- cium channel blockers and angiotensin-II receptor blockers for Raynaud phenomenon, appropriate treatments for gastroesophageal reflux disease) and lifestyle modifications can help prevent complications, such as digital ulcers and Barrett esophagus. Endothelin-1 receptor blockers and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors improve pulmonary arte- rial hypertension. The risk of renal damage from scleroderma renal crisis can be lessened by early detection, prompt initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy, and avoidance of high-dose corticosteroids. Optimal patient care includes an integrated, multidisciplinary approach to promptly and effectively recognize, evaluate, and manage complications and limit end-organ dysfunction. -

CNS Vasculitis As a Manifestation of Systemic Sclerosis Corey E

CNS Vasculitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Sclerosis Corey E. Goldsmith, MD and Joseph S. Kass, MD Department of Neurology, Ben Taub General Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX Harris County Hospital District Neither author has anything to disclose INTRODUCTION CASE REPORT, cont DISCUSSION Systemic sclerosis (or scleroderma) is a connective tissue Figure 1. CT and MRI Brain Imaging Systemic sclerosis is a connective tissue disease of disease manifested by rapidly progressive fibrosis of the skin, unknown etiology which causes rapidly progressive fibrosis of lungs, and other internal organs usually felt to have rare the skin, lungs, and other internal organs. Currently, cranial secondary central nervous system (CNS) manifestations. We and autonomic neuropathies are widely recognized present a patient with extensive CNS involvement of systemic neurological associations with systemic sclerosis, but central sclerosis consistent with a diffuse CNS vasculitis. Recent nervous system manifestations are much rarer. This case evidence supports a more direct role of the central nervous A B C shows the most extensive involvement of the central nervous system in systemic sclerosis. system in systemic sclerosis of which we are aware with CASE REPORT serologic and imaging evidence of vasculitis. Previous literature has hypothesized that the CNS A 24 year-old right-handed woman with a two year history involvement in systemic sclerosis is due to a secondary of advanced systemic sclerosis treated with prednisone 10mg DE vasculopathy. However, there is argument for a more primary daily presented with a week-long history of progressive CT head without contrast (A) shows multiple calcifications. MRI FLAIR (B) involvement of the central nervous system. -

Case Report Scleroderma Renal Crisis As an Initial Presentation of Systemic Sclerosis: a Case Report and Review of the Literature K.M

Case report Scleroderma renal crisis as an initial presentation of systemic sclerosis: a case report and review of the literature K.M. Logee, S. Lakshminarayanan Division of Rheumatology, University ABSTRACT precipitously. An evaluation for hae- of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, Scleroderma renal crisis (SRC) is a life- molysis revealed an elevated serum lac- Connecticut, USA. threatening complication of systemic tate dehydrogenase which rose to 1155 Kristin M. Logee, DO sclerosis (SSc) that is characterised U/L and an undetectably low hapto- Santhanam Lakshminarayanan, MD by new-onset malignant hypertension globin. Peripheral smear showed schis- Please address correspondence and progressive acute renal failure, of- tocytes with evidence of microangio- and reprint requests to: ten with associated microangiopathic pathic haemolytic anaemia (MAHA). Dr Kristin M. Logee, haemolytic anaemia and thrombocy- Division of Rheumatology, The patient was thought to have throm- University of Connecticut Health Center, topenia. SRC was at one time almost botic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) 263 Farmington Avenue, uniformly fatal, with death often occur- with MAHA and treated with methyl- Farmington, ring within a few weeks. With the de- prednisolone 1g IV daily for 3 days and Connecticut 06030, USA. velopment of angiotensin-converting- plasmapheresis. ADAMTS13 level was E-mail: [email protected] enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), survival ordered. Received on March 21, 2014; accepted in has improved dramatically, but death Over the next several days, despite revised form on November 24, 2014. rates still remain unacceptably high. treatment for TTP, the patient’s condi- Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015; 33 (Suppl. 91): About 20% of SRC cases occur prior to tion continued to worsen. -

Necrobiosis Lipoidica: Ultrastructural and Biochemical Demonstration of a Collagen Defect

Necrobiosis Lipoidica: Ultrastructural and Biochemical Demonstration of a Collagen Defect Aarne Oikarinen, M .D ., Ph. D., Minna Mo rtenhul11 cr, M .D ., M atti Kallioincn, M .D., Ph.D., and Eeva-Riitta Savolainen, M. D., Ph.D. Coll agen Resea rch Unit, Unive rsity of O Ulll , Departmcnts of Dc n1l3tology (AO, MM ), Anatomy (AO), Pathology (MK), and Medi ca l Biochcmistry (AO, E-RS), Uni ve rsity of O ulu , O Ulll , Finl and T en pati ents with necrobiosis lipoidica lesions were stud lagen was unchanged in the affected skin . Fibrobl asts ied. Five pati ents had diabetes mellitus. The age of the es tablished fr o m affected skin synthesized less coll agen than patients vari ed from 15 to 73 yea rs and the durati on o f the ce ll s deri ved fr om hea lth y-looking skin. T he decreased col skin lesions w as fro m 2 to 20 yea rs. Histologica ll y, the lagen synthesis was due to a decreased amount of m essen lesions w ere characterized by degeneration of coll agen and ger RN A fo r type I procoll agen, m easured by hybridization elas tin. In som e lesions el as tin fibers could be seen in areas w ith a specific human cDN A cl one. T he producti on of devoid of normal-looking coll agen. Electron microscopy colla genase by these fib robl as ts was not in creased. O ur revea led loss of cross-striation of coHa gen fibrils and a marked res ults thus indica te that in necro bi osis lipoidica lesions, vari atio n in the diameter o f individual coll agen fibrils. -

Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma with Scleroderma

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma With Scleroderma Glenn G. Russo, MD GOAL To understand the presentation and treatment of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this activity, dermatologists and general practitioners should be able to: 1. Explain the laboratory and histopathology results in NXG. 2. Discuss the theoretical pathogenesis of NXG. 3. Describe the treatment options for NXG. CME Test on page 317. This article has been peer reviewed and Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide approved by Michael Fisher, MD, Professor of continuing medical education for physicians. Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Albert Einstein College of Medicine designates Review date: November 2002. this educational activity for a maximum of 1.0 hour This activity has been planned and implemented in category 1 credit toward the AMA Physician’s in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies Recognition Award. Each physician should claim of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical only those hours of credit that he/she actually spent Education through the joint sponsorship of Albert in the educational activity. Einstein College of Medicine and Quadrant This activity has been planned and produced in HealthCom, Inc. The Albert Einstein College of accordance with ACCME Essentials. Dr. Russo reports no conflict of interest. The author reports off-label use of the following medications: extracorporeal photophoresis, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, nitrogen mustard, adrenocorticotropic hormone, azathioprine, radiation therapy, plasmapheresis, hydroxychloroquine, thalidomide, and etretinate. Dr. Fisher reports no conflict of interest. I report the case of a 68-year-old man who pre- exposure to cold temperatures. This is an interest- sented with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) ing constellation of findings in this rare disorder with concomitant scleroderma, along with the pres- that raises questions concerning its pathogenesis. -

What Is Scleroderma?

What is scleroderma? 1. The word scleroderma comes from the Greek words: “sclero” meaning hard, and “derma” meaning skin. 2. Scleroderma, is a complicated, chronic disease that affects a person’s connective tissues and is characterized by an overproduction of collagen. Scleroderma is categorized as an autoimmune disease. Current thinking suggests that the disease is set into motion through a combination of a genetic predisposition and an environmental trigger. 3. Scleroderma affects about 300,000 people in the United States, about one in every thousand. The number of people affected worldwide is unknown, but the disease has been reported all across the globe. 4. Scleroderma is the umbrella term for a variety of pathways which a patient may be affected. The two basic types of scleroderma are limited and diffuse (aka systemic sclerosis). 5. The exact cause or causes of scleroderma are unknown. Scientists and researchers are working hard to find the cause. 6. Women are 3 to 4 times more likely than men to develop the disease. 7. The disease commonly starts between the ages of 25 and 55, but it can occur at any age. 8. Scleroderma varies in symptoms and severity from patient-to-patient. Some patients have visible signs of the disease such as tight, skinny skin or changes in skin pigmentation. Many others deal with symptoms that are invisible to others yet are life-altering such as problems with the heart, lungs, esophagus, digestive system, blood vessels and kidneys. Some of the typical diseases that are associated with scleroderma include: Raynaud’s Phenomenon, Sjogren’s Syndrome, pulmonary fibrosis, renal crisis/failure, interstitial lung disease, GERD, irritable bowel syndrome and many more.