American Indians of the Chesapeake Bay: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

The First People of Virginia a Social Studies Resource Unit for K-6 Students

The First People of Virginia A Social Studies Resource Unit for K-6 Students Image: Arrival of Englishmen in Virginia from Thomas Harriot, A Brief and True Report, 1590 Submitted as Partial Requirement for EDUC 405/ CRIN L05 Elementary Social Studies Curriculum and Instruction Professor Gail McEachron Prepared By: Lauren Medina: http://lemedina.wmwikis.net/ Meagan Taylor: http://mltaylor01.wmwikis.net Julia Vans: http://jcvans.wmwikis.net Historical narrative: All group members Lesson One- Map/Globe skills: All group members Lesson Two- Critical Thinking and The Arts: Julia Vans Lesson Three-Civic Engagement: Meagan Taylor Lesson Four-Global Inquiry: Lauren Medina Artifact One: Lauren Medina Artifact Two: Meagan Taylor Artifact Three: Julia Vans Artifact Four: Meagan Taylor Assessments: All group members 2 The First People of Virginia Introduction The history of Native Americans prior to European contact is often ignored in K-6 curriculums, and the narratives transmitted in schools regarding early Native Americans interactions with Europeans are often biased towards a Euro-centric perspective. It is important, however, for students to understand that American History did not begin with European exploration. Rather, European settlement in North America must be contextualized within the framework of the pre-existing Native American civilizations they encountered upon their arrival. Studying Native Americans and their interactions with Europeans and each other prior to 1619 aligns well with National Standards for History as well as Virginia Standards of Learning (SOLs), which dictate that students should gain an understanding of diverse historical origins of the people of Virginia. There are standards in every elementary grade level that are applicable to this topic of study including Virginia SOLs K.1, K.4, 1.7, 1.12, 2.4, 3.3, VS.2d, VS.2e, VS.2f and WHII.4 (see Appendix A). -

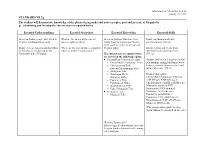

STANDARD VS.2G

Attachment A, Memo No. 014-13 January 18, 2013 STANDARD VS.2g The student will demonstrate knowledge of the physical geography and native peoples, past and present, of Virginia by g) identifying and locating the current state-recognized tribes. Essential Understandings Essential Questions Essential Knowledge Essential Skills American Indian people have lived in What are the names of the current American Indians, who trace their Draw conclusions and make Virginia for thousands of years. state-recognized tribes? family histories back to well before generalizations. (VS.1d) 1607, continue to live in all parts of Today, eleven† American Indian tribes Where are the current state-recognized Virginia today. Interpret ideas and events from in Virginia are recognized by the tribes located in Virginia today? different historical perspectives. Commonwealth of Virginia. The current state-recognized tribes (VS.1g) are located in the following regions: Coastal Plain (Tidewater) region: Analyze and interpret maps to explain – Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Tribe† relationships among landforms, water – Chickahominy Tribe features, climatic characteristics, and – Eastern Chickahominy Tribe historical events. (VS.1i) – Mattaponi Tribe – Nansemond Tribe Pronunciation guide: – Nottoway Tribe† Cheroenhaka (Nottoway): Chair-oh- – Pamunkey Tribe en-HAH-kah (NAH-toh-way)† – Patawomeck Tribe† Chickahominy: CHICK-a-HOM-a-nee – Rappahannock Tribe Mattaponi: ma-ta-po-NYE – Upper Mattaponi Tribe Nansemond: NAN-sa-mund Piedmont region: Nottoway: NAH-toh-way† – Monacan Tribe Pamunkey: pa-MUN-kee Patawomeck: Pət- OW-ə-meck† Rappahannock: RAP-a-HAN-nock Monacan: MON-a-cun (The pronunciation guide for these words will not be assessed on the test.) †Revised January 2013 These technical edits will not affect the Virginia Studies Standards of Learning test at this time. -

Defining the Nanticoke Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Indigenous Cultural Landscapes Study for the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail: Nanticoke River Watershed December 2013 Kristin M. Sullivan, M.A.A. - Co-Principal Investigator Erve Chambers, Ph.D. - Principal Investigator Ennis Barbery, M.A.A. - Research Assistant Prepared under cooperative agreement with The University of Maryland College Park, MD and The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, MD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Nanticoke River watershed indigenous cultural landscape study area is home to well over 100 sites, landscapes, and waterways meaningful to the history and present-day lives of the Nanticoke people. This report provides background and evidence for the inclusion of many of these locations within a high-probability indigenous cultural landscape boundary—a focus area provided to the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay and the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Advisory Council for the purposes of future conservation and interpretation as an indigenous cultural landscape, and to satisfy the Identification and Mapping portion of the Chesapeake Watershed Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Cooperative Agreement between the National Park Service and the University of Maryland, College Park. Herein we define indigenous cultural landscapes as areas that reflect “the contexts of the American Indian peoples in the Nanticoke River area and their interaction with the landscape.” The identification of indigenous cultural landscapes “ includes both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife therein associated with historic lifestyle and settlement patterns and exhibiting the cultural or esthetic values of American Indian peoples,” which fall under the purview of the National Park Service and its partner organizations for the purposes of conservation and development of recreation and interpretation (National Park Service 2010:4.22). -

Governor's Commission on Indian Affairs Annual Report

Governor’s Commission on Indian Affairs Annual Report 2011 Mission Statement The Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs works to serve as a statewide clearinghouse for information; to identify unmet social and economic needs in the native community; to support government education programs for American Indian youth; to provide support in the process of obtaining Recognition of State and Federal Indian Status; and to promote the awareness and understanding of historical and contemporary American Indian contributions in Maryland. 2 Table of Contents Message from the Governor …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Message from the Executive Director, Governor’s Office of Community Initiatives…………….5 Message from the Chair, Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs………………………………………6 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Commissioners……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Commission Meeting Schedule…………………………………………………………………………………………..9 State and Federal Agency Partner Meetings and Events …………………………………………………….10 State Recognition…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....11 2011 initiatives…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 Outreach………………………………………………………………………………………………................................14 Commissioners in Action…………………………………………………………………………………………………….15 Resident Population………………………………………………………………………………………………………….17 Maryland Indigenous Tribes………………………………………………………………………………………………19 3 STATE OF MARYLAND OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR MARTIN O’MALLEY GOVERNOR STATE HOUSE 100 STATE Circle ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND -

ELECT-643 Voter Identification Chart

Voter Identification All voters casting a ballot in-person will be asked to show one form of identification. Any voter who does not present acceptable photo identification must vote a provisional ballot. Identification Is it accepted? Valid1 photo ID Yes, if issued by an employer; the U.S. or Virginia government; or a school, college, or university located in Virginia Government-issued photo ID card from a federal, VA, or local Yes political subdivision Valid DMV-issued photo ID card Yes Valid Tribal enrollment or other tribal ID Yes, if issued by one of the 11 tribes recognized by VA** Valid U.S. passport or passport card Yes Valid employee ID card issued by voter’s employer in ordinary Yes course of business (public or private employer) Credit card displaying a photograph No Membership card from private organization displaying a photograph No U.S. Military photo ID Yes Photo IDs Nursing home resident photo ID Yes, if issued by government facility Voter photo ID card issued by the Department of Elections Yes Valid student photo ID issued by a public or private school of higher Yes education located in VA Valid student photo ID issued by a public high school in VA Yes Valid student photo ID issued by a private high school in VA Yes Valid Virginia driver’s license or DMV-issued photo ID Yes Valid out-of-state driver’s license No Virginia voter photo identification requirements: Va. Code § 24.2-643(B) Valid Virginia driver's license Valid United States passport Any other photo identification card issued by a government agency of the Commonwealth, one of its political subdivisions, or the United States Valid student identification card containing a photograph of the voter issued by any institution of higher education located in the Commonwealth of Virginia Any valid employee identification card containing a photograph of the voter and issued by an employer of the voter in the ordinary course of the employer's business * “Valid” means the document is genuine, bears the photograph of the voter, and is not expired for more than 12 months. -

Preservation and Partners: a History of Piscataway Park

Preservation and Partners: A History of Piscataway Park Janet A. McDonnell, PhD December 2020 Resource Stewardship and Science, National Capital Area, National Park Service and Organization of American Historians EXECUTIVE SUMMARY During the early republic period of American history, President George Washington was the most renowned resident of the Potomac River valley. His sprawling Mount Vernon estate sat on a hill directly across the Potomac River from the 17th century Marshall Hall estate in Maryland. There is ample evidence that Washington and his guests enjoyed and very much appreciated the stunning view. Many years later preserving this view would become the major impetus for establishing what we know today as Piscataway Park (PISC), a few miles south of Washington, DC. These lands along the Maryland shore of Potomac River were actively cultivated during George Washington’s time, and the existing park setting, which includes agricultural lands and open spaces interspersed with forests and wetlands, closely approximates that historic scene. The National Park Service’s (NPS) primary goal and responsibility in managing the park has been, and continues to be, preserving this historic scene of open fields and wooded areas and ensuring that it does not authorize any landscape alterations except those that would restore previously undisturbed sites, reduce visual intrusions, or maintain open fields. The NPS continues to take into account the slope and orientation of the terrain and the tree cover when considering the location of any new facilities. Piscataway Park and its associated lands are for the most part held under scenic easements and constitute a National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) historic district made up of nearly 5,000 acres of meadow, woodland, and wetland, along six miles of the Potomac River shoreline from the head of Piscataway Creek to the historic Marshall Hall in Maryland’s Prince George’s and Charles counties. -

American Tri-Racials

DISSERTATIONEN DER LMU 43 RENATE BARTL American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America We People: Multi-Ethnic Indigenous Nations and Multi- Ethnic Groups Claiming Indian Ancestry in the Eastern United States Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Renate Bartl aus Mainburg 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Berndt Ostendorf Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Eveline Dürr Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 26.02.2018 Renate Bartl American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America Dissertationen der LMU München Band 43 American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America by Renate Bartl Herausgegeben von der Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1 80539 München Mit Open Publishing LMU unterstützt die Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München alle Wissenschaft ler innen und Wissenschaftler der LMU dabei, ihre Forschungsergebnisse parallel gedruckt und digital zu veröfentlichen. Text © Renate Bartl 2020 Erstveröfentlichung 2021 Zugleich Dissertation der LMU München 2017 Bibliografsche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografe; detaillierte bibliografsche Daten sind im Internet abrufbar über http://dnb.dnb.de Herstellung über: readbox unipress in der readbox publishing GmbH Rheinische Str. 171 44147 Dortmund http://unipress.readbox.net Open-Access-Version dieser Publikation verfügbar unter: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-268747 978-3-95925-170-9 (Druckausgabe) 978-3-95925-171-6 (elektronische Version) Contents List of Maps ........................................................................................................ -

The Pocomoke Nation

Page 1 of 2 THE POCOMOKE NATION Website: www.pocomokeindiannation.org email: [email protected] BACKGROUND The Pocomoke is one of several indigenous nations who called present-day Delmarva their home. Its people were culturally aligned with the Algonquian language family and regionally identified as a Northeastern Woodland group. It is likely the Pocomoke had prehistoric roots to the Shawnee, an Algonquin group who traditionally considered the Lenape as “their grandfathers.” Giovanni da Verrazano in 1524 observed the native people on the Assateague peninsula. In 1649 Norwood’s ship became stranded off the coast and he and a party of men rowed ashore and requested assistance from the natives to reach the western shore and the English settlement at Jamestown. In 1608 Captain John Smith explored the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay and visited a palisaded town and King’s house on the Wighco Flu, now known as the Pocomoke River. According to Capt. Smith these People and its northern neighbor, the Nanticoke, spoke a different dialect than the Accomac and Accohannock groups who he noted were politically and culturally associated with the Powhatan Empire across the Chesapeake Bay. Verrazano’s observations, Norwood’s detailed account and Smith’s journals present an early view of Pocomoke hospitality to strangers and a window in its culture prior to English colonization. SUBTRIBES & TOWNS Early records identify the sub-tribes of the Pocomoke Paramountcy as Annemessee, Acquintica, Gingoteague, Manoakin, Monie, Morumsco, Nusswattux, Pocomoke and Quandanquan, and its towns and villages as Askiminokansen, Arrococo, Monie, Manoakin, Parahockin, and Wighcocomoco. TERRITORY The Pocomoke paramount chiefdom and territory ran from the Chesapeake Bay to the confluence of the Nanticoke and Wicomico rivers, then northeasterly to the Ocean, encompassing forests, swamps, coastal bays and seaside islands. -

Upper Potomac Buoy History

Upper Potomac Buoy History Historians believe that Capt. John Smith and his crew passed by this point in their Discovery Barge twice in June 1608. The first time was on June 22 when they headed upriver as they explored the Potomac and searched in vain for the Northwest Passage through the continent to the Pacific Ocean. Several days before, they had stopped briefly 40 miles downstream on today's Potomac Creek to visit the Patawomeck chief and his people, the farthest-upstream tribe thought to be allies of the paramount chief Powhatan. Scholars reconstructing this part of the expedition believe that the reception the Englishmen received at Patawomeck was chilly, so they crossed the river and followed the Maryland shoreline to the more welcoming Piscataway people at the towns of Nussamek, near today's Mallows Bay, and Pamacocack, just inside the mouth of Mattawoman Creek, where General Smallwood State Park is located now. They also returned to the Virginia side to visit Tauxenent, inside the mouth of today's Occoquan River. The people in the Piscataway communities urged Smith to visit their paramount chief, or tayac, at Moyaons, which is still sacred ground to the Piscataway people today but which also houses the National Colonial Farm (which is open to the public), just below the mouth of Piscataway Creek. The Piscataway tayac welcomed Smith and the crew and feasted them, we believe on the evening of June 21. The next day, well-fed and rested, the English took their Discovery Barge upriver past this point for an overnight visit with the Anacostan people at the town of Nacotchtank, located on the south side of the mouth of the Anacostia River, at the current site of Bolling Air Force Base. -

Voter Identification Card

Voter Identification All voters will be asked to show one form of identification. Any voter who does not have identification required by state or federal law must vote a provisional ballot. Identification Is it accepted? Valid* photo ID Yes, if issued by government, employer, or institute of higher education in VA. Government-issued ID card from federal, VA, or local subdivision Yes (including political subdivisions) DMV-Issued Photo ID Card Yes Tribal enrollment or other tribal ID Yes, if issued by one of 11 tribes recognized by VA.** US Passport or Passport Card Yes Valid* employee ID card issued by voter’s employer in ordinary Yes course of business (public or private employer) Photo IDs Photo Credit card displaying photograph No Membership card from private organization No Military ID Yes Nursing home resident ID Yes, if issued by government facility. Voter Photo Identification Card issued by the Department of Yes Elections Identification Is it accepted? Valid* student ID issued by a public or private school of higher Yes education located in VA displaying photo Valid* student ID issued by a public or private school of higher No education outside of VA displaying photo Student ID issued by a public high school in VA displaying a photo Yes Student IDs Student ID issued by a private high school in VA displaying a photo No Valid* Virginia Driver’s License or DMV-issued Photo ID Yes Virginia Driver’s License that is expired Yes operating state - Valid* out-of-state driver’s license No Driver’s or License non identification Virginia requirements: Va. -

Teacher's Guide – First Inquiry

dawnland TEACHER’S GUIDE – FIRST INQUIRY BY DR. MISHY LESSER A DOCUMENTARY ABOUT CULTURAL SURVIVAL AND STOLEN CHILDREN BY ADAM MAZO AND BEN PENDER-CUDLIP COPYRIGHT © 2019 MISHY LESSER AND UPSTANDER FILMS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS DAWNLAND TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................................3 B. PREPARING TO TEACH DAWNLAND .................................................................................................................17 C. THE COMPELLING QUESTION TO SUPPORT INQUIRY .........................................................................................22 D. FIRST INQUIRY: FROM TURTLE ISLAND TO THE AMERICAS ...................................................................................24 The First Inquiry spans millennia, beginning tens of thousands of years ago and ending in the eighteenth century with scalp proclamations that targeted Native people for elimination. Many important moments, events, documents, sources, and voices were left out of the lessons you are about to read because they can be accessed elsewhere. We encourage teachers to consult and use the excellent resources developed by Tribal educators, such as: • Since Time Immemorial: Tribal Sovereignty in Washington State • Indian Education for All (Montana) • Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators Lesson 1: The peopling of Turtle Island ...............................................................................................................