Preservation and Partners: a History of Piscataway Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

To View the 10-Year Solid Waste Management Plan for 2020-2029

“Prince George’s County 2020 – 2029 Solid Waste Management Plan” CR-50-2020 (DR-2) 2020 – 2029 COMPREHENSIVE TEN-YEAR SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN Prince George’s County, Maryland Acknowledgements Marilyn E. Rybak-Naumann, Resource Recovery Division, Associate Director Denice E. Curry, Resource Recovery Division, Recycling Section, Section Manager Darryl L. Flick, Resource Recovery Division, Special Assistant Kevin Roy B. Serrona, Resource Recovery Division, Recycling Section, Planner IV Antoinette Peterson, Resource Recovery Division, Administrative Aide Michael A. Bashore, Stormwater Management Division, Planner III/GIS Analyst With Thanks To all of the agencies and individuals who contributed data “Prince George’s County 2020 – 2029 Solid Waste Management Plan” CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. State Requirements for Preparation of the Plan.…………………………………..1 II. Plan Summary…………………………………………………………………….. 1 A. Solid Waste Generation………………………………………………………. 2 B. Solid Waste Collection……………………………………………………….. 2 C. Solid Waste Disposal…………………………………………………………. 2 D. Recycling……………………………………………………………………... 2 E. Public Information and Cleanup Programs………………………………….... 3 III. Place Holder – Insertion of MDE’s Approval Letter for Adopted Plan……………4 CHAPTER I POLICIES AND ORGANIZATION I. Planning Background……………………………………………………………... I-1 II. Solid Waste Management Terms…………………………………………………. I-1 III. County Goals Statement………………………………………………………….. I-2 IV. County Objectives and Policies Concerning Solid Waste Management………..... I-3 A. General Objectives of the Ten-Year Solid Waste Management Plan………... I-4 B. Guidelines and Policies regarding Solid Waste Facilities……………………. I-4 V. Governmental Responsibilities…………………………………………………… I-5 A. Prince George’s County Government………………………………………… I-5 B. Maryland Department of the Environment…………………………………… I-9 C. Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission…………………. I-9 D. Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC)………………………. I-9 VI. State, Local, and Federal Laws…………………………………………………… I-9 A. -

Bladensburg Prehistoric Background

Environmental Background and Native American Context for Bladensburg and the Anacostia River Carol A. Ebright (April 2011) Environmental Setting Bladensburg lies along the east bank of the Anacostia River at the confluence of the Northeast Branch and Northwest Branch of this stream. Formerly known as the East Branch of the Potomac River, the Anacostia River is the northernmost tidal tributary of the Potomac River. The Anacostia River has incised a pronounced valley into the Glen Burnie Rolling Uplands, within the embayed section of the Western Shore Coastal Plain physiographic province (Reger and Cleaves 2008). Quaternary and Tertiary stream terraces, and adjoining uplands provided well drained living surfaces for humans during prehistoric and historic times. The uplands rise as much as 300 feet above the water. The Anacostia River drainage system flows southwestward, roughly parallel to the Fall Line, entering the Potomac River on the east side of Washington, within the District of Columbia boundaries (Figure 1). Thin Coastal Plain strata meet the Piedmont bedrock at the Fall Line, approximately at Rock Creek in the District of Columbia, but thicken to more than 1,000 feet on the east side of the Anacostia River (Froelich and Hack 1975). Terraces of Quaternary age are well-developed in the Bladensburg vicinity (Glaser 2003), occurring under Kenilworth Avenue and Baltimore Avenue. The main stem of the Anacostia River lies in the Coastal Plain, but its Northwest Branch headwaters penetrate the inter-fingered boundary of the Piedmont province, and provided ready access to the lithic resources of the heavily metamorphosed interior foothills to the west. -

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Anacostia River Watershed Restoration Plan

Restoration Plan for the Anacostia River Watershed in Prince George’s County December 30, 2015 RUSHERN L. BAKER, III COUNTPreparedY EXECUTIV for:E Prince George’s County, Maryland Department of the Environment Stormwater Management Division Prepared by: 10306 Eaton Place, Suite 340 Fairfax, VA 22030 COVER PHOTO CREDITS: 1. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 7. USEPA 2. Tetra Tech, Inc. 8. USEPA 3. Prince George’s County 9. Montgomery Co DEP 4. VA Tech, Center for TMDL and 10. PGC DoE Watershed Studies 11. USEPA 5. Charles County, MD Dept of 12. PGC DoE Planning and Growth Management 13. USEPA 6. Portland Bureau of Environmental Services _Tom Liptan Anacostia River Watershed Restoration Plan Contents Acronym List ............................................................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of Report and Restoration Planning ............................................................................... 3 1.1.1 What is a TMDL? ................................................................................................................ 3 1.1.2 What is a Restoration Plan? ............................................................................................... 4 1.2 Impaired Water Bodies and TMDLs .............................................................................................. 6 1.2.1 Water Quality Standards .................................................................................................... -

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland Founding the Proprietary Colony The founding and establishment of the propriety government of Maryland was the product of competing factors—political, commercial, social, and religious. It was intertwined with the history of one family, the Calverts, who were well established among the Yorkshire gentry and whose Catholic sympathies were widely known. George Calvert had been a favorite of the Stuart king, James I. In 1625, following a noteworthy career in politics, including periods as clerk of the Privy Council, member of Parliament, special emissary abroad of the king, and a principal secretary of state, Calvert openly declared his Catholicism. This declaration closed any future possibility of public office for him. Shortly thereafter, James elevated Calvert to the Irish peerage as the baron of Baltimore. Calvert’s absence from public office afforded him an opportunity to pursue his interests in overseas colonization. Calvert appealed to Charles I, son of James, for a land grant.1 Calvert’s appeal was honored, but he did not live to see a charter issued. In 1632, Charles granted a proprietary charter to Cecil Calvert, George’s son and the second baron of Baltimore, making him Maryland’s first proprietor. Maryland’s charter was the first long-lasting one of its kind to be issued among the thirteen mainland British American colonies. Proprietorships represented a real share in the king’s authority. They extended unusual power. Maryland’s charter, which constituted Calvert and his heirs as “the true and absolute Lords and Proprietaries of the Region,” might have been “the best example of a sweeping grant of power to a proprietor.” Proprietors could award land grants, confer titles, and establish courts, which included the prerogative of hearing appeals. -

Shoreline Situation Report Stafford County, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1975 Shoreline Situation Report Stafford County, Virginia Carl H. Hobbs III Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gary F. Anderson Virginia Institute of Marine Science Dennis W. Owen Virginia Institute of Marine Science Peter Rosen Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Hobbs, C. H., Anderson, G. F., Owen, D. W., & Rosen, P. (1975) Shoreline Situation Report Stafford County, Virginia. Special Report In Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 79. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V5PB01 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shoreline Situation Report ST AFFORD COUNTY, VIRGINIA Special Report In Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 79 Chesapeake Research Consortium Report Number 13 Supported by the National Science Foundation, Research Applied to National Needs Program NSF Grant Nos. GI 34869 and GI 38973 to the Chesapeake Research Consortium, Inc. Published With Funds Provided to the Commonwealth by the Office of Coastal Zone Management National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Grant No. 04-5-158-50001 VIRGINIA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1975 Shoreline Situation Report ST AFFORD COUNTY, VIRGINIA Special Report In Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 79 Chesapeake Research Consortium Report Number 13 Prepared by: Carl H. -

Turning Point

National Parks Conservation Association® Protecting Our National Parks for Future Generations® Turning Point Will we continue to protect against air pollution threats to the Habitats, Health, Heritage, and Horizons of our national parks? Or will we fail to save them for future generations? PHOTOS FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: BIG STOCK PHOTO, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, SCOTT KIRKWOOD, BIG STOCK PHOTO National Park Sites Located in Poor Air Quality Areas as Designated by the EPA (continued on inside back cover) ALABAMA San Francisco Maritime NHP Potomac Heritage NST Fort Washington Park Russell Cave NM Santa Monica Rock Creek Park Greenbelt Park Mountains NRA Theodore Roosevelt Island George Washington ARIZONA Sequoia NP Thomas Jefferson MEM Memorial PKWY Casa Grande Ruins NM Yosemite NP Vietnam Veterans MEM Hampton NHS Chiricahua NM Washington Monument Harpers Ferry NHP Coronado NMEM COLORADO White House Monocacy NB Fort Bowie NHS Rocky Mountains NP National Capital Parks Grand Canyon NP GEORGIA CONNECTICUT Piscataway Park Hohokam Pima NM Chattahoochee River NRA Appalachian NST Thomas Stone NHS Organ Pipe Cactus NM Chickamauga & Weir Farm NHS Saguaro NP Chattanooga NMP MASSACHUSETTS Tonto NM DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Kennesaw Mountain NBP Cape Cod NS Tumacacori NHP Chesapeake & Ohio Martin Luther King, Jr. NHS Adams NHP Canal NHP Ocmulgee NM Appalachian NST CALIFORNIA Carter G. Woodson NHS Boston African- Cabrillo NM INDIANA Constitution Gardens American NHS Channel Islands NP Indiana Dunes NL Franklin Delano Boston Harbor Islands NRA Death Valley NP Lincoln -

Potomac River Basin Assessment Overview

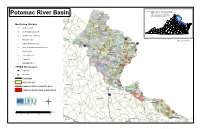

Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality PL01 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Potomac River Basin Virginia Geographic Information Network PL03 PL04 United States Geological Survey PL05 Winchester PL02 Monitoring Stations PL12 Clarke PL16 Ambient (120) Frederick Loudoun PL15 PL11 PL20 Ambient/Biological (60) PL19 PL14 PL23 PL08 PL21 Ambient/Fish Tissue (4) PL10 PL18 PL17 *# 495 Biological (20) Warren PL07 PL13 PL22 ¨¦§ PL09 PL24 draft; clb 060320 PL06 PL42 Falls ChurchArlington jk Citizen Monitoring (35) PL45 395 PL25 ¨¦§ 66 k ¨¦§ PL43 Other Non-Agency Monitoring (14) PL31 PL30 PL26 Alexandria PL44 PL46 WX Federal (23) PL32 Manassas Park Fairfax PL35 PL34 Manassas PL29 PL27 PL28 Fish Tissue (15) Fauquier PL47 PL33 PL41 ^ Trend (47) Rappahannock PL36 Prince William PL48 PL38 ! PL49 A VDH-BEACH (1) PL40 PL37 PL51 PL50 VPDES Dischargers PL52 PL39 @A PL53 Industrial PL55 PL56 @A Municipal Culpeper PL54 PL57 Interstate PL59 Stafford PL58 Watersheds PL63 Madison PL60 Impaired Rivers and Streams PL62 PL61 Fredericksburg PL64 Impaired Reservoirs or Estuaries King George PL65 Orange 95 ¨¦§ PL66 Spotsylvania PL67 PL74 PL69 Westmoreland PL70 « Albemarle PL68 Caroline PL71 Miles Louisa Essex 0 5 10 20 30 Richmond PL72 PL73 Northumberland Hanover King and Queen Fluvanna Goochland King William Frederick Clarke Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Loudoun Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Rappahannock River Basin -

American Indians of the Chesapeake Bay: an Introduction

AMERICAN INDIANS OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY: AN INTRODUCTION hen Captain John Smith sailed up the Chesapeake Bay in 1608, American Indians had W already lived in the area for thousands of years. The people lived off the land by harvesting the natural resources the Bay had to offer. In the spring, thousands of shad, herring and rockfish were netted as they entered the Chesapeake’s rivers and streams to spawn. Summer months were spent tending gardens that produced corn, beans and squash. In the fall, nuts such as acorns, chestnuts and walnuts were gathered from the forest floor. Oysters and clams provided another source of food and were easily gathered from the water at low tide. Hunting parties were sent overland in search of deer, bear, wild turkey and other land animals. Nearby marshes provided wild rice and tuckahoe (arrow arum), which produced a potato-like root. With so much food available, the American Indians of the Chesapeake region were able to thrive. Indian towns were found close to the water’s edge near freshwater springs or streams. Homes were made out of bent saplings (young, Captain John Smith and his exploring party encounter two Indian men green trees) that were tied into a spearing fish in the shallows on the lower Eastern Shore. The Indians framework and covered with woven later led Smith to the village of Accomack, where he met with the chief. mats, tree bark, or animal skins. Villages often had many homes clustered together, and some were built within a palisade, a tall wall built with sturdy sticks and covered with bark, for defense. -

Public Access Points Within 50 Miles of Capitol Hill

Public Access Points within 50 Miles of Capitol Hill Public Access Point Boat Ramp Fishing Swimming Restrooms Hiking/Trekking Location 2900 Virginia Ave NW, Thompson's Boat Center X X X X Washington, DC 20037 3244 K St NW, Washington, DC Georgetown Waterfront Park X X 20007 George Washington Memorial Theodore Roosevelt Island X X X Pkwy N, Arlington, VA 22209 West Basin Dr SW, Washington, West Potomac Park X X DC 20024 Capital Crescent Trail, Washington Canoe Club X Washington, DC 20007 600 Water St SW, Washington, DC Ganglplank Marina X X X X 20024 George Washington Memorial Columbia Island Marina X X X Parkway, Arlington, VA 22202 99 Potomac Ave. SE. Washington, Diamond Teague Park X X DC 20003 335 Water Street Washington, DC The Yards Park X 20003 Martin Luther King Jr Ave SE, Anacostia Boat House X Washington, DC 20003 700-1000 Water St SW, Washington Marina X X X X Washington, DC 20024 Anacostia Park, Section E Anacostia Marina X X X Washington, DC 20003 2001-2099 1st St SW, Washington, Buzzard's Point Marina X X X DC 20003 2038-2068 2nd St SW, James Creek Marina X X X Washington, DC 20593 Anacostia Dr, Washington, DC Anacostia Park X X X 20019 Heritage Island Trail, Washington, Heritage Island X DC 20002 Kingman Island Trail, Washington, Kingman Island X DC 20002 Mt Vernon Trail, Arlington, VA Gravelly Point X X 22202 George Washington Memorial Roaches Run X X X X Pkwy, Arlington, VA 22202 1550 Anacostia Ave NE, Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens/Park X X X Washington, DC 20019 Capital Crescent Trail, Jack's Boat House X X Washington, DC 20007 Daingerfield Island X X X X 1 Marina Dr, Alexandria, VA 22314 67-101 Dale St, Alexandria, VA Four Mile Run Park/Trail X X X 22305 4601 Annapolis Rd. -

Board of County Commissioners of Washington County, Maryland V. Perennial Solar, LLC, No. 66, September Term, 2018, Opinion by Booth, J

Board of County Commissioners of Washington County, Maryland v. Perennial Solar, LLC, No. 66, September Term, 2018, Opinion by Booth, J. MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS – IMPLIED PREEMPTION – CONCURRENT AND CONFLICTING EXERCISE OF POWER BY STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT State law impliedly preempts local zoning regulation of solar energy generating systems (“SEGS”) that require a certificate of public convenience and necessity (“CPCN”). Maryland Code, Public Utilities Article § 7-207 grants the Maryland Public Service Commission broad authority to determine whether and where a SEGS may be operated. Circuit Court for Washington County Case No.: 21-C-15-055848 Argued: May 2, 2019 IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND No. 66 September Term, 2018 BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OF WASHINGTON COUNTY, MARYLAND v. PERENNIAL SOLAR, LLC Barbera, C.J. *Greene McDonald Watts Hotten Getty Booth, JJ. Opinion by Booth, J. Filed: July 15, 2019 *Greene, J., now retired, participated in the hearing and conference of this case while an active member of this Court; after being recalled pursuant to the MD. Constitution, Article IV, Section 3A, he also participated in the decision and adoption of this opinion. “Here comes the sun, and I say, It’s all right.” -The Beatles, “Here Comes the Sun” This case involves the intersection of the State’s efforts to promote solar electric generation as part of its renewable energy policies, and local governments’ interest in ensuring compliance with local planning and zoning prerogatives. In this matter, we are asked to determine whether state law preempts local zoning authority with respect to solar energy generating systems that require a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity (“CPCN”) issued by the Maryland Public Service Commission.