The First People of Virginia a Social Studies Resource Unit for K-6 Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

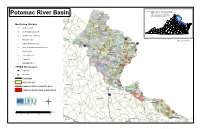

Potomac River Basin Assessment Overview

Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality PL01 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Potomac River Basin Virginia Geographic Information Network PL03 PL04 United States Geological Survey PL05 Winchester PL02 Monitoring Stations PL12 Clarke PL16 Ambient (120) Frederick Loudoun PL15 PL11 PL20 Ambient/Biological (60) PL19 PL14 PL23 PL08 PL21 Ambient/Fish Tissue (4) PL10 PL18 PL17 *# 495 Biological (20) Warren PL07 PL13 PL22 ¨¦§ PL09 PL24 draft; clb 060320 PL06 PL42 Falls ChurchArlington jk Citizen Monitoring (35) PL45 395 PL25 ¨¦§ 66 k ¨¦§ PL43 Other Non-Agency Monitoring (14) PL31 PL30 PL26 Alexandria PL44 PL46 WX Federal (23) PL32 Manassas Park Fairfax PL35 PL34 Manassas PL29 PL27 PL28 Fish Tissue (15) Fauquier PL47 PL33 PL41 ^ Trend (47) Rappahannock PL36 Prince William PL48 PL38 ! PL49 A VDH-BEACH (1) PL40 PL37 PL51 PL50 VPDES Dischargers PL52 PL39 @A PL53 Industrial PL55 PL56 @A Municipal Culpeper PL54 PL57 Interstate PL59 Stafford PL58 Watersheds PL63 Madison PL60 Impaired Rivers and Streams PL62 PL61 Fredericksburg PL64 Impaired Reservoirs or Estuaries King George PL65 Orange 95 ¨¦§ PL66 Spotsylvania PL67 PL74 PL69 Westmoreland PL70 « Albemarle PL68 Caroline PL71 Miles Louisa Essex 0 5 10 20 30 Richmond PL72 PL73 Northumberland Hanover King and Queen Fluvanna Goochland King William Frederick Clarke Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Loudoun Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Rappahannock River Basin -

American Indians of the Chesapeake Bay: an Introduction

AMERICAN INDIANS OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY: AN INTRODUCTION hen Captain John Smith sailed up the Chesapeake Bay in 1608, American Indians had W already lived in the area for thousands of years. The people lived off the land by harvesting the natural resources the Bay had to offer. In the spring, thousands of shad, herring and rockfish were netted as they entered the Chesapeake’s rivers and streams to spawn. Summer months were spent tending gardens that produced corn, beans and squash. In the fall, nuts such as acorns, chestnuts and walnuts were gathered from the forest floor. Oysters and clams provided another source of food and were easily gathered from the water at low tide. Hunting parties were sent overland in search of deer, bear, wild turkey and other land animals. Nearby marshes provided wild rice and tuckahoe (arrow arum), which produced a potato-like root. With so much food available, the American Indians of the Chesapeake region were able to thrive. Indian towns were found close to the water’s edge near freshwater springs or streams. Homes were made out of bent saplings (young, Captain John Smith and his exploring party encounter two Indian men green trees) that were tied into a spearing fish in the shallows on the lower Eastern Shore. The Indians framework and covered with woven later led Smith to the village of Accomack, where he met with the chief. mats, tree bark, or animal skins. Villages often had many homes clustered together, and some were built within a palisade, a tall wall built with sturdy sticks and covered with bark, for defense. -

York River Water Budget

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1-29-2009 York River Water Budget Carl Hershner Virginia Institute of Marine Science Molly Mitchell Virginia Institute of Marine Science Donna Marie Bilkovic Virginia Institute of Marine Science Julie D. Herman Virginia Institute of Marine Science Center for Coastal Resources Management, Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons, Hydrology Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Recommended Citation Hershner, C., Mitchell, M., Bilkovic, D. M., Herman, J. D., & Center for Coastal Resources Management, Virginia Institute of Marine Science. (2009) York River Water Budget. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V56S39 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YORK RIVER WATER BUDGET REPORT By the Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science January 29, 2009 Authors: Carl Hershner Molly Roggero Donna Bilkovic Julie Herman Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................. 3 Methods of determining instream flow requirement ....................................................................... 4 Hydrological methods..................................................................................................................... -

STANDARD VS.2G

Attachment A, Memo No. 014-13 January 18, 2013 STANDARD VS.2g The student will demonstrate knowledge of the physical geography and native peoples, past and present, of Virginia by g) identifying and locating the current state-recognized tribes. Essential Understandings Essential Questions Essential Knowledge Essential Skills American Indian people have lived in What are the names of the current American Indians, who trace their Draw conclusions and make Virginia for thousands of years. state-recognized tribes? family histories back to well before generalizations. (VS.1d) 1607, continue to live in all parts of Today, eleven† American Indian tribes Where are the current state-recognized Virginia today. Interpret ideas and events from in Virginia are recognized by the tribes located in Virginia today? different historical perspectives. Commonwealth of Virginia. The current state-recognized tribes (VS.1g) are located in the following regions: Coastal Plain (Tidewater) region: Analyze and interpret maps to explain – Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Tribe† relationships among landforms, water – Chickahominy Tribe features, climatic characteristics, and – Eastern Chickahominy Tribe historical events. (VS.1i) – Mattaponi Tribe – Nansemond Tribe Pronunciation guide: – Nottoway Tribe† Cheroenhaka (Nottoway): Chair-oh- – Pamunkey Tribe en-HAH-kah (NAH-toh-way)† – Patawomeck Tribe† Chickahominy: CHICK-a-HOM-a-nee – Rappahannock Tribe Mattaponi: ma-ta-po-NYE – Upper Mattaponi Tribe Nansemond: NAN-sa-mund Piedmont region: Nottoway: NAH-toh-way† – Monacan Tribe Pamunkey: pa-MUN-kee Patawomeck: Pət- OW-ə-meck† Rappahannock: RAP-a-HAN-nock Monacan: MON-a-cun (The pronunciation guide for these words will not be assessed on the test.) †Revised January 2013 These technical edits will not affect the Virginia Studies Standards of Learning test at this time. -

Unsuuseuracsbe

W in Centreville Chantilly ARLINGTON c LOUDOUN Fairfax Rd h Jefferson Lake e DISTRICT Bailey’s Arlington s Barcroft te Crossroads r Manassas 8 Natl Battlefield Pk FAIRFAX Annandale 15 Mantua L ittle R US Naval Station Washington Upper Marlboro 66 iver T Lincolnia Morningside Shady Side pke 395 Washington DC Laboratory 29 495 Marlow Heights Haymarket Lee Hwy 66 Alexandria Andrews North Temple Hills AFB Springfield Camp Andrews Greater Upper Deale Gainesville Forest Miles Oxon Hill-GlassmanorSprings AFB Marlboro ANNE ARUNDEL River Sudley Yorkshire FAIRFAX Huntington Heights Crest Hill Rd West Springfield Rose Hill St. Michaels Wilson Rd 17 West Burke Springfield DISTRICT Bull Gate DISTRICT Tracys Creek Lieber Army Run Reserve Ctr Belle Haven 108th Congress of the United States Clifton Burke Lake 8 Rosaryville 10 wy Loch Jug Bay ee H L Linton Hall Lomond S Clinton t Marlton 29 Manassas ( R Groveton O te Fort Friendly x 1 Hybla Vint Hill Rd R 2 Belvoir Franconia Telecom and S d 3 Info Systems Valley t Manassas ) Military Res Mitchell Harrison Rd R Park Command Broad Creek Warrenton te PRINCE (Alexandria Cheltenham- Dumfries Rd 2 Cannonball Gate Rd 1 WILLIAM Newington Station) Naval Foster Ln 5 ( Fort Belvoir Communications Unit-W Vint H d Old Waterloo Rd Rogues Rd ill Rd) DISTRICT DISTRICT Military Res on Harris m ch Fort Hunt Creek 10 Ri y 11 Hw Fort Dunkirk p y Mount Washington Owings wy 211 B Vernon Tilghman Island H n North Beach r Tred Avon River ee 1 George L L e e t 95 Fort Dogue Washington e s Lorton Mem Pkwy H a Nokesville Belvoir Creek E wy Lake Ridge Chesapeake Beach Occoquan Oxford Trappe Gunston RAPPAHANNOCK Cove Dale Accokeek Brandywine Occoquan 15 FAUQUIER City River Minnieville Rd Woodbridge A de Waldorf ) n Rd d y Cedar Run R w t t H le S at ( tR n (C D te o 8 um Spriggs Rd Cow s 2 i 2 fr 34 ) d te i Br Bryans d e TALBOT a tR s R R S d) Bennsville Huntingtown M St. -

Defining the Greater York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Defining the Greater York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape Prepared by: Scott M. Strickland Julia A. King Martha McCartney with contributions from: The Pamunkey Indian Tribe The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe The Mattaponi Indian Tribe Prepared for: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay & Colonial National Historical Park The Chesapeake Conservancy Annapolis, Maryland The Pamunkey Indian Tribe Pamunkey Reservation, King William, Virginia The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe Adamstown, King William, Virginia The Mattaponi Indian Tribe Mattaponi Reservation, King William, Virginia St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland October 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As part of its management of the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, the National Park Service (NPS) commissioned this project in an effort to identify and represent the York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape. The work was undertaken by St. Mary’s College of Maryland in close coordination with NPS. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept represents “the context of the American Indian peoples in the Chesapeake Bay and their interaction with the landscape.” Identifying ICLs is important for raising public awareness about the many tribal communities that have lived in the Chesapeake Bay region for thousands of years and continue to live in their ancestral homeland. ICLs are important for land conservation, public access to, and preservation of the Chesapeake Bay. The three tribes, including the state- and Federally-recognized Pamunkey and Upper Mattaponi tribes and the state-recognized Mattaponi tribe, who are today centered in their ancestral homeland in the Pamunkey and Mattaponi river watersheds, were engaged as part of this project. The Pamunkey and Upper Mattaponi tribes participated in meetings and driving tours. -

Remembering the River: Traditional Fishery Practices, Environmental Change and Sovereignty on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2019 Remembering the River: Traditional Fishery Practices, Environmental Change and Sovereignty on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation Alexis Jenkins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jenkins, Alexis, "Remembering the River: Traditional Fishery Practices, Environmental Change and Sovereignty on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1423. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1423 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Pamunkey Chief and Tribal Council for their support of this project, as well as the Pamunkey community members who shared their knowledge and perspectives with this researcher. I am incredibly honored to have worked under the guidance of Dr. Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, who has been a dedicated and inspiring mentor from the beginning. I also thank Dr. Ashley Atkins Spivey for her assistance as Pamunkey Tribal Liaison and for her review of my thesis as a member of the committee and am further thankful for the comments of committee members Dr. Martin Gallivan and Dr. Andrew Fisher, who provided valuable insight during the process. I would like to express my appreciation to the VIMS scientists who allowed me to volunteer with their lab and to the The Roy R. -

Comprehensive Plan

SPOTSYLVANIA COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Adopted by the Spotsylvania County Board of Supervisors November 14, 2013 Updated: June 14, 2016 August 9, 2016 May 22, 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to the many people who contributed to development of this Comprehensive Plan. The Spotsylvania County Board of Supervisors Ann L. Heidig David Ross Emmitt B. Marshall Gary F. Skinner Timothy J. McLaughlin Paul D. Trampe Benjamin T. Pitts The Spotsylvania County Planning Commission Mary Lee Carter Richard H. Sorrell John F. Gustafson Robert Stuber Cristine Lynch Richard Thompson Scott Mellott The Citizen Advisory Groups Land Use Scott Cook Aviv Goldsmith Daniel Mahon Lynn Smith M.R. Fulks Suzanne Ircink Eric Martin Public Facilities Mike Cotter Garrett Garner Horace McCaskill Chris Folger George Giddens William Nightingale Transportation James Beard M.R. Fulks Mike Shiflett Mark Vigil Rupert Farley Greg Newhouse Dale Swanson Historic & Natural Resources Mike Blake Claude Dunn Larry Plating George Tryfiates John Burge Donna Pienkowski Bonita Tompkins C. Douglas Barnes, County Administrator, and County Staff Spotsylvania County Comprehensive Plan Adopted November 14, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction and Vision Chapter 2 Land Use Future Land Use Map Future Land Use Map – Primary Development Boundary Zoom Chapter 3 Transportation & Thoroughfare Plan Thoroughfare Plan List Thoroughfare Plan Map Chapter 4 Public Facilities Plan General Government Map Public Schools Map Public Safety Map Chapter 5 Historic Resources Chapter 6 Natural Resources Appendix A Land Use – Fort A.P. Hill Approach Fan Map Appendix B Public Facilities – Parks and Recreation Appendix C Historic Resources Appendix D Natural Resources Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION AND VISION INTRODUCTION AND VISION – Adopted 11/14/2013; Updated 6/14/2016 & 5/22/2018 Page 1 INTRODUCTION The Spotsylvania County Comprehensive Plan presents a long range land use vision for the County. -

ELECT-643 Voter Identification Chart

Voter Identification All voters casting a ballot in-person will be asked to show one form of identification. Any voter who does not present acceptable photo identification must vote a provisional ballot. Identification Is it accepted? Valid1 photo ID Yes, if issued by an employer; the U.S. or Virginia government; or a school, college, or university located in Virginia Government-issued photo ID card from a federal, VA, or local Yes political subdivision Valid DMV-issued photo ID card Yes Valid Tribal enrollment or other tribal ID Yes, if issued by one of the 11 tribes recognized by VA** Valid U.S. passport or passport card Yes Valid employee ID card issued by voter’s employer in ordinary Yes course of business (public or private employer) Credit card displaying a photograph No Membership card from private organization displaying a photograph No U.S. Military photo ID Yes Photo IDs Nursing home resident photo ID Yes, if issued by government facility Voter photo ID card issued by the Department of Elections Yes Valid student photo ID issued by a public or private school of higher Yes education located in VA Valid student photo ID issued by a public high school in VA Yes Valid student photo ID issued by a private high school in VA Yes Valid Virginia driver’s license or DMV-issued photo ID Yes Valid out-of-state driver’s license No Virginia voter photo identification requirements: Va. Code § 24.2-643(B) Valid Virginia driver's license Valid United States passport Any other photo identification card issued by a government agency of the Commonwealth, one of its political subdivisions, or the United States Valid student identification card containing a photograph of the voter issued by any institution of higher education located in the Commonwealth of Virginia Any valid employee identification card containing a photograph of the voter and issued by an employer of the voter in the ordinary course of the employer's business * “Valid” means the document is genuine, bears the photograph of the voter, and is not expired for more than 12 months. -

An Amicus Brief

Case 1:17-cv-01574-RCL Document 51 Filed 12/15/17 Page 1 of 5 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA __________________________________________ ) NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC ) PRESERVATION IN THE UNITED STATES ) and ASSOCIATION FOR THE PRESERVATION ) OF VIRGINIA ANTIQUITIES, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil No. 1:17-CV-01574-RCL ) TODD T. SEMONITE, Lieutenant General, U.S. ) Army Corps of Engineers and DR. MARK T. ) ESPER),1 Secretary of the Army, ) ) Defendants, ) ) VIRGINIA ELECTRIC & POWER COMPANY, ) ) Defendant-Intervenor. ) __________________________________________) MATTAPONI INDIAN TRIBE’S MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AN AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS The Mattaponi Indian Tribe (“Tribe” or “Mattaponi”) moves this Court for leave, pursuant to Local Civil Rule 7(o), to file an amicus curiae brief in support of Plaintiffs National Trust for Historic Preservation and Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. In support of this motion, the Tribe states as follows: 1. The Mattaponi Indian Tribe is recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia and was one of the six original tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy. About sixty-five members of the Tribe currently reside on the Mattaponi Reservation near West Point, Virginia, and an additional 1 Pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 25(d), Dr. Mark T. Esper, the Secretary of the United States Army, is automatically substituted for former Acting Secretary of the Army Robert M. Speer. Case 1:17-cv-01574-RCL Document 51 Filed 12/15/17 Page 2 of 5 approximately 4,000 Mattaponi Indian Tribal members and persons eligible for membership live across Virginia and elsewhere. -

Upper Potomac Buoy History

Upper Potomac Buoy History Historians believe that Capt. John Smith and his crew passed by this point in their Discovery Barge twice in June 1608. The first time was on June 22 when they headed upriver as they explored the Potomac and searched in vain for the Northwest Passage through the continent to the Pacific Ocean. Several days before, they had stopped briefly 40 miles downstream on today's Potomac Creek to visit the Patawomeck chief and his people, the farthest-upstream tribe thought to be allies of the paramount chief Powhatan. Scholars reconstructing this part of the expedition believe that the reception the Englishmen received at Patawomeck was chilly, so they crossed the river and followed the Maryland shoreline to the more welcoming Piscataway people at the towns of Nussamek, near today's Mallows Bay, and Pamacocack, just inside the mouth of Mattawoman Creek, where General Smallwood State Park is located now. They also returned to the Virginia side to visit Tauxenent, inside the mouth of today's Occoquan River. The people in the Piscataway communities urged Smith to visit their paramount chief, or tayac, at Moyaons, which is still sacred ground to the Piscataway people today but which also houses the National Colonial Farm (which is open to the public), just below the mouth of Piscataway Creek. The Piscataway tayac welcomed Smith and the crew and feasted them, we believe on the evening of June 21. The next day, well-fed and rested, the English took their Discovery Barge upriver past this point for an overnight visit with the Anacostan people at the town of Nacotchtank, located on the south side of the mouth of the Anacostia River, at the current site of Bolling Air Force Base.