Remembering the River: Traditional Fishery Practices, Environmental Change and Sovereignty on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piedmont District Clubs by Counties

Piedmont District of Virginia Federation of Garden Clubs Below is a list of member Garden Clubs by county or city. Location is listed by mailing address of club president. This is not necessarily representative of all club members nor necessarily where the club holds its meeting. However, this is a good approximation. Check clubs listed in neighboring counties and cities as well. If you are interested in contacting a club please send us an email from the ‘Contact’ page and someone will be in contact with you. Thank you! Clubs by Counties Amelia -Clay Spring GC Middlesex -Amelia County GC -Hanover Herb Guild -John Mitchell GC Arlington -Hanover Towne GC -Rock Spring GC -Newfound River GC New Kent Brunswick -Old Ivy GC -Hanover Towne GC Caroline -Pamunkey River GC Charles City -West Hanover GC Northumberland -Chesapeake Bay GC Chesterfield Henrico -Kilmarnock -Bon Air GC -Crown Grant GC -Rappahannock GC -Chester GC -Ginter Park GC -Crestwood Farms GC -Green Acres GC Nottoway -Glebe Point GC -Highland Springs GC -Crewe -Greenfield GC -Hillard Park GC -Midlothian GC -Northam GC Powhatan -Oxford GC - Richmond Designers’ -Powhatan - Richmond Designers’ Guild* Guild* -River Road GC Prince William -Salisbury GC -Roslyn Hills GC -Manassas GC -Stonehenge GC -Sleepy Hollow GC -Woodland Pond GC -Thomas Jefferson GC Prince George -Windsordale GC Richmond County Cumberland -Wyndham GC Southampton -Cartersville GC Spotsylvania Dinwiddie James City -Chancellor GC Essex King and Queen -Sunlight GC Fairfax King George Fluvanna King William Stafford -Fluvanna GC Lancaster Surry Goochland Louisa -Surry GC Greensville -Lake Anna GC Sussex -Sunlight GC Westmoreland Hanover Lunenburg -Westmoreland GC -Canterbury GC Page 1 of 2 *Members of Richmond Designers’ Guild are members of other garden clubs and are from all areas. -

Proposed Finding

This page is intentionally left blank. Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) Proposed Finding Proposed Finding The Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 Regulatory Procedures .............................................................................................1 Administrative History.............................................................................................2 The Historical Indian Tribe ......................................................................................4 CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR 83.7) ..............................................9 Criterion 83.7(a) .....................................................................................................11 Criterion 83.7(b) ....................................................................................................21 Criterion 83.7(c) .....................................................................................................57 Criterion 83.7(d) ...................................................................................................81 Criterion 83.7(e) ....................................................................................................87 Criterion 83.7(f) ...................................................................................................107 -

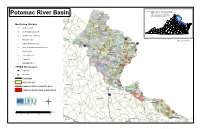

Potomac River Basin Assessment Overview

Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality PL01 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Potomac River Basin Virginia Geographic Information Network PL03 PL04 United States Geological Survey PL05 Winchester PL02 Monitoring Stations PL12 Clarke PL16 Ambient (120) Frederick Loudoun PL15 PL11 PL20 Ambient/Biological (60) PL19 PL14 PL23 PL08 PL21 Ambient/Fish Tissue (4) PL10 PL18 PL17 *# 495 Biological (20) Warren PL07 PL13 PL22 ¨¦§ PL09 PL24 draft; clb 060320 PL06 PL42 Falls ChurchArlington jk Citizen Monitoring (35) PL45 395 PL25 ¨¦§ 66 k ¨¦§ PL43 Other Non-Agency Monitoring (14) PL31 PL30 PL26 Alexandria PL44 PL46 WX Federal (23) PL32 Manassas Park Fairfax PL35 PL34 Manassas PL29 PL27 PL28 Fish Tissue (15) Fauquier PL47 PL33 PL41 ^ Trend (47) Rappahannock PL36 Prince William PL48 PL38 ! PL49 A VDH-BEACH (1) PL40 PL37 PL51 PL50 VPDES Dischargers PL52 PL39 @A PL53 Industrial PL55 PL56 @A Municipal Culpeper PL54 PL57 Interstate PL59 Stafford PL58 Watersheds PL63 Madison PL60 Impaired Rivers and Streams PL62 PL61 Fredericksburg PL64 Impaired Reservoirs or Estuaries King George PL65 Orange 95 ¨¦§ PL66 Spotsylvania PL67 PL74 PL69 Westmoreland PL70 « Albemarle PL68 Caroline PL71 Miles Louisa Essex 0 5 10 20 30 Richmond PL72 PL73 Northumberland Hanover King and Queen Fluvanna Goochland King William Frederick Clarke Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Loudoun Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Rappahannock River Basin -

EPA Interim Evaluation of Virginia's 2016-2017 Milestones

Interim Evaluation of Virginia’s 2016-2017 Milestones Progress June 30, 2017 EPA INTERIM EVALUATION OF VIRGINIA’s 2016-2017 MILESTONES As part of its role in the accountability framework, described in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (Bay TMDL) for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing this interim evaluation of Virginia’s progress toward meeting its statewide and sector-specific two-year milestones for the 2016-2017 milestone period. In 2018, EPA will evaluate whether each Bay jurisdiction achieved the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) partnership goal of practices in place by 2017 that would achieve 60 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions necessary to achieve applicable water quality standards in the Bay compared to 2009. Load Reduction Review When evaluating 2016-2017 milestone implementation, EPA is comparing progress to expected pollutant reduction targets to assess whether statewide and sector load reductions are on track to have practices in place by 2017 that will achieve 60 percent of necessary reductions compared to 2009. This is important to understand sector progress as jurisdictions develop the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIP). Loads in this evaluation are simulated using version 5.3.2 of the CBP partnership Watershed Model and wastewater discharge data reported by the Bay jurisdictions. According to the data provided by Virginia for the 2016 progress run, Virginia is on track to achieve its statewide 2017 targets for nitrogen and phosphorus but is off track to meet its statewide targets for sediment. The data also show that, at the sector scale, Virginia is off track to meet its 2017 targets for nitrogen reductions in the Agriculture, Urban/Suburban Stormwater and Septic sectors and is also off track for phosphorus in the Urban/Suburban Stormwater sector, and off track for sediment in the Agriculture and Urban/Suburban Stormwater sectors. -

NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC Placet MULTIPLE PROPERTY

NFS Form 10-900-b 4-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACEt SHGISfER, HISTORY MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION F RM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing The Civil War in Virginia, 1861-1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Civil War in Virginia, 1861-1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources C. Form Prepared by name/title John S. Salmon organization _Virginia Department of Historic Resources street & number 2801 Kensington Avenue telephone 804-367-2323 ext. 117 city or town Richmond_____________ state VA zip code 23221 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. (__ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature and title of certifying official Date of tate or FeaeraHgency and ureau I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Blue Catfish in Virginia Historical Perspective & Importance To

Blue Catfish in Virginia Historical Perspective & Importance to Recreational Fishing David K. Whitehurst [email protected] Blue Catfish Introductions to James River & Rappahannock River 1973 - 1977 N James River Tidal James River Watershed Rappahannock River Tidal Rappahannock Watershed USGS Hydrologic Boundaries Blue Catfish Introduced to Mattaponi River in 1985 Blue CatfishFollowed ( Ictalurus by Colonization furcatus ) Introductions of the Pamunkey York River River System Mattaponi River 1985 Pamunkey River ???? N James River Tidal James River Watershed Rappahannock River Tidal Rappahannock Watershed York River Tidal York Watershed USGS Hydrologic Boundaries Blue Catfish Established in Potomac River – Date ? Blue Catfish ( Ictalurus furcatus ) Introductions EstablishedConfirmed in in Potomac Piankatank River (SinceRiver ????)– 2002 Recently Discovered in Piankatank River N Piankatank / Dragon Swamp Tidal Potomac - Virginia James River Tidal James River Watershed Rappahannock River Tidal Rappahannock Watershed York River Tidal York Watershed USGS Hydrologic Boundaries Blue Catfish Now Occur in all Major Virginia Blue Catfish ( Ictalurus furcatus ) Tributaries of Chesapeake Bay All of Virginia’s Major Tidal River Systems of Chesapeake Bay Drainage 2003 N Piankatank / Dragon Swamp Tidal Potomac - Virginia Tidal James River Watershed Tidal Rappahannock Watershed Tidal York Watershed USGS Hydrologic Boundaries Stocking in Virginia – Provide recreational and food value to anglers – Traditional Fisheries Management => Stocking – Other species introduced to Virginia tidal rivers: – Channel Catfish, – Largemouth Bass, – Smallmouth Bass, – Common carp, …. Blue catfish aside, as of mid-1990’s freshwater fish community in Virginia tidal waters dominated by introduced species. Blue Catfish Introductions Widespread Important Recreational Fisheries • Key factors determining this “success” – Strong recruitment and good survival leading to very high abundance – Trophy fishery dependant on rapid growth and good survival > 90 lb. -

York River Water Budget

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1-29-2009 York River Water Budget Carl Hershner Virginia Institute of Marine Science Molly Mitchell Virginia Institute of Marine Science Donna Marie Bilkovic Virginia Institute of Marine Science Julie D. Herman Virginia Institute of Marine Science Center for Coastal Resources Management, Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons, Hydrology Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Recommended Citation Hershner, C., Mitchell, M., Bilkovic, D. M., Herman, J. D., & Center for Coastal Resources Management, Virginia Institute of Marine Science. (2009) York River Water Budget. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V56S39 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YORK RIVER WATER BUDGET REPORT By the Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science January 29, 2009 Authors: Carl Hershner Molly Roggero Donna Bilkovic Julie Herman Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................. 3 Methods of determining instream flow requirement ....................................................................... 4 Hydrological methods..................................................................................................................... -

The First People of Virginia a Social Studies Resource Unit for K-6 Students

The First People of Virginia A Social Studies Resource Unit for K-6 Students Image: Arrival of Englishmen in Virginia from Thomas Harriot, A Brief and True Report, 1590 Submitted as Partial Requirement for EDUC 405/ CRIN L05 Elementary Social Studies Curriculum and Instruction Professor Gail McEachron Prepared By: Lauren Medina: http://lemedina.wmwikis.net/ Meagan Taylor: http://mltaylor01.wmwikis.net Julia Vans: http://jcvans.wmwikis.net Historical narrative: All group members Lesson One- Map/Globe skills: All group members Lesson Two- Critical Thinking and The Arts: Julia Vans Lesson Three-Civic Engagement: Meagan Taylor Lesson Four-Global Inquiry: Lauren Medina Artifact One: Lauren Medina Artifact Two: Meagan Taylor Artifact Three: Julia Vans Artifact Four: Meagan Taylor Assessments: All group members 2 The First People of Virginia Introduction The history of Native Americans prior to European contact is often ignored in K-6 curriculums, and the narratives transmitted in schools regarding early Native Americans interactions with Europeans are often biased towards a Euro-centric perspective. It is important, however, for students to understand that American History did not begin with European exploration. Rather, European settlement in North America must be contextualized within the framework of the pre-existing Native American civilizations they encountered upon their arrival. Studying Native Americans and their interactions with Europeans and each other prior to 1619 aligns well with National Standards for History as well as Virginia Standards of Learning (SOLs), which dictate that students should gain an understanding of diverse historical origins of the people of Virginia. There are standards in every elementary grade level that are applicable to this topic of study including Virginia SOLs K.1, K.4, 1.7, 1.12, 2.4, 3.3, VS.2d, VS.2e, VS.2f and WHII.4 (see Appendix A). -

Sewage and Wastewater Plants in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed 21 Sewage Plants Violated Permit Limits in 2016; PA and VA Used Trading to Allow Pollution

Sewage and Wastewater Plants in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed 21 Sewage Plants Violated Permit Limits in 2016; PA and VA Used Trading to Allow Pollution NOVEMBER 29, 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was researched and written by Courtney Bernhardt and Tom Pelton of the Environmental Integrity Project. THE ENVIRONMENTAL INTEGRITY PROJECT The Environmental Integrity Project (http://www.environmentalintegrity.org) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization established in March of 2002 by former EPA enforcement attorneys to advocate for effective enforcement of environmental laws. EIP has three goals: 1) to provide objective analyses of how the failure to enforce or implement environmental laws increases pollution and affects public health; 2) to hold federal and state agencies, as well as individual corporations, accountable for failing to enforce or comply with environmental laws; and 3) to help local communities obtain the protection of environmental laws. For questions about this report, please contact EIP Director of Communications Tom Pelton at (202) 888-2703 or [email protected]. PHOTO CREDITS Cover photo of Patapsco Wastewater Treatment Plant from University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. Photo of Back River WWTP by Tom Pelton. Photo of Monocacy River by Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Photo of Massanutten Wastewater Treatment Plant by Alan Lehman. Sewage and Wastewater Plants in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Executive Summary Across the Chesapeake Bay watershed, 21 sewage treatment plants violated their permit limits last year by releasing excessive amounts of nitrogen or phosphorus pollution that fuel algal blooms and low-oxygen “dead zones” in waterways, according to an Environmental Integrity Project examination of federal and state records.1 The plants in violation included 12 municipal sewage facilities in Maryland that treat more than half of the state’s wastewater, with the most pollution coming from the state’s largest two facilities: Baltimore’s Back River and Patapsco wastewater treatment plants. -

Unsuuseuracsbe

W in Centreville Chantilly ARLINGTON c LOUDOUN Fairfax Rd h Jefferson Lake e DISTRICT Bailey’s Arlington s Barcroft te Crossroads r Manassas 8 Natl Battlefield Pk FAIRFAX Annandale 15 Mantua L ittle R US Naval Station Washington Upper Marlboro 66 iver T Lincolnia Morningside Shady Side pke 395 Washington DC Laboratory 29 495 Marlow Heights Haymarket Lee Hwy 66 Alexandria Andrews North Temple Hills AFB Springfield Camp Andrews Greater Upper Deale Gainesville Forest Miles Oxon Hill-GlassmanorSprings AFB Marlboro ANNE ARUNDEL River Sudley Yorkshire FAIRFAX Huntington Heights Crest Hill Rd West Springfield Rose Hill St. Michaels Wilson Rd 17 West Burke Springfield DISTRICT Bull Gate DISTRICT Tracys Creek Lieber Army Run Reserve Ctr Belle Haven 108th Congress of the United States Clifton Burke Lake 8 Rosaryville 10 wy Loch Jug Bay ee H L Linton Hall Lomond S Clinton t Marlton 29 Manassas ( R Groveton O te Fort Friendly x 1 Hybla Vint Hill Rd R 2 Belvoir Franconia Telecom and S d 3 Info Systems Valley t Manassas ) Military Res Mitchell Harrison Rd R Park Command Broad Creek Warrenton te PRINCE (Alexandria Cheltenham- Dumfries Rd 2 Cannonball Gate Rd 1 WILLIAM Newington Station) Naval Foster Ln 5 ( Fort Belvoir Communications Unit-W Vint H d Old Waterloo Rd Rogues Rd ill Rd) DISTRICT DISTRICT Military Res on Harris m ch Fort Hunt Creek 10 Ri y 11 Hw Fort Dunkirk p y Mount Washington Owings wy 211 B Vernon Tilghman Island H n North Beach r Tred Avon River ee 1 George L L e e t 95 Fort Dogue Washington e s Lorton Mem Pkwy H a Nokesville Belvoir Creek E wy Lake Ridge Chesapeake Beach Occoquan Oxford Trappe Gunston RAPPAHANNOCK Cove Dale Accokeek Brandywine Occoquan 15 FAUQUIER City River Minnieville Rd Woodbridge A de Waldorf ) n Rd d y Cedar Run R w t t H le S at ( tR n (C D te o 8 um Spriggs Rd Cow s 2 i 2 fr 34 ) d te i Br Bryans d e TALBOT a tR s R R S d) Bennsville Huntingtown M St. -

Reports Which Would Describe the Condi- Routes 30 and 360 in the Upper Portion of the County

King William County Shoreline Situation Report Supported by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Comprehensive Coastal Inventory Program, and the Virginia Coastal Resources Management Program at the Depart- ment of Environmental Quality through Grant # NA770Z0204 of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Manage- ment, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. Prepared By (in alphabetical order): Marcia Berman Harry Berquist Sharon Dewing Julie Glover Carl Hershner Tamia Rudnicky Dan Schatt Kevin Skunda Project Supervisors: Marcia Berman - Director, Comprehensive Coastal Inventory Program Carl Hershner - Director, Center for Coastal Resources Management Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering No. 367 of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science January, 2001 Cover Design by Harold Burrell, photo by Dwight Dyke. CHAPTER I - Introduction 1.1 Background systems within the county, and the drainage areas of both extend well beyond 1.4 Report Organization the county limits. A number of small creeks and tributaries feed the larger rivers. This report is divided into several sections. Chapter 2 describes meth- In the 1970s, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) received a King William is rural in character, with more than two-thirds of its land ods used to develop this inventory, along with conditions and attributes consid- grant through the National Science Foundation’s Research Applied to National area covered with forest vegetation. Development is most prevalent along ered in the survey. Chapter 3 identifies potential applications for the data, with Needs Program to develop a series of reports which would describe the condi- routes 30 and 360 in the upper portion of the county. -

Defining the Greater York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Defining the Greater York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape Prepared by: Scott M. Strickland Julia A. King Martha McCartney with contributions from: The Pamunkey Indian Tribe The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe The Mattaponi Indian Tribe Prepared for: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay & Colonial National Historical Park The Chesapeake Conservancy Annapolis, Maryland The Pamunkey Indian Tribe Pamunkey Reservation, King William, Virginia The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe Adamstown, King William, Virginia The Mattaponi Indian Tribe Mattaponi Reservation, King William, Virginia St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland October 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As part of its management of the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, the National Park Service (NPS) commissioned this project in an effort to identify and represent the York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape. The work was undertaken by St. Mary’s College of Maryland in close coordination with NPS. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept represents “the context of the American Indian peoples in the Chesapeake Bay and their interaction with the landscape.” Identifying ICLs is important for raising public awareness about the many tribal communities that have lived in the Chesapeake Bay region for thousands of years and continue to live in their ancestral homeland. ICLs are important for land conservation, public access to, and preservation of the Chesapeake Bay. The three tribes, including the state- and Federally-recognized Pamunkey and Upper Mattaponi tribes and the state-recognized Mattaponi tribe, who are today centered in their ancestral homeland in the Pamunkey and Mattaponi river watersheds, were engaged as part of this project. The Pamunkey and Upper Mattaponi tribes participated in meetings and driving tours.