On the Status of the Partitive Determiner in Italian∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

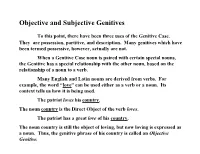

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Finnish Partitive Case As a Determiner Suffix

Finnish partitive case as a determiner suffix Problem: Finnish partitive case shows up on subject and object nouns, alternating with nominative and accusative respectively, where the interpretation involves indefiniteness or negation (Karlsson 1999). On these grounds some researchers have proposed that partitive is a structural case in Finnish (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001). A problematic consequence of this is that Finnish is assumed to have a structural case not found in other languages, losing the universal inventory of structural cases. I will propose an alternative, namely that partitive be analysed instead as a member of the Finnish determiner class. Data: There are three contexts in which the Finnish subject is in the partitive (alternating with the nominative in complementary contexts): (i) indefinite divisible non-count nouns (1), (ii) indefinite plural count nouns (2), (iii) where the existence of the argument is completely negated (3). The data are drawn from Karlsson (1999:82-5). (1) Divisible non-count nouns a. Partitive mass noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative mass noun = def Purki-ssa on leipä-ä. Leipä on purki-ssa. tin-INESS is bread-PART Bread is tin-INESS ‘There is some bread in the tin.’ ‘The bread is in the tin.’ (2) Plural count nouns a. Partitive count noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative count noun = def Kadu-lla on auto-j-a. Auto-t ovat kadulla. Street-ADESS is.3SG car-PL-PART Car-PL are.3PL street-ADESS ‘There are cars in the street.’ ‘The cars are in the street.’ (3) Negation a. Partitive, negation of existence b. c.f. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayerau Osijeku Filozofskifakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Pedagogije Anja Kolobarić A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations Završni rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc Gabrijela Buljan Osijek, 2014. Summary This research paper explores partitive expressions not only as devices that impose countable readings in uncountable nouns, but also as a means of directing the interpretive focus on different aspects of the uncountable entities denoted by nouns. This exploration was made possible through a close examination of specific grammar books, but also through a small-scale corpus study we have conducted. We first explain the theory behind uncountable nouns and partitive expressions, and then present the results of our corpus study, demonstrating thereby the creative nature of the English language. We also propose some cautious generalizations concerning the distribution of partitive expressions within the analyzed semantic domains. Key words: noncount noun, concrete noun, partitive expression, corpus data, data analysis 2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 4 2. Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 Distinction between Count and Noncount -

The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish

Absolutely a Matter of Degree: The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish Paul Kiparsky CLS, April 2005 1. Functional categories (1) What are the functional categories of a language? A proposal. a. Syntax: functional categories are projected by functional heads. b. Morphology: functional categories are assigned by affixes or inherently marked on lexical items. c. Null elements may mark default values in paradigmatic system of functional categories. d. Otherwise functional categories are not specified. (2) a. Diachronic evidence: syntactic projections of functional categories emerge hand in hand with lexical heads (e.g. Kiparsky 1996, 1997 on English, Condoravdi and Kiparsky 2002, 2004 on Greek.) b. Empirical arguments from morphology (e.g. Kiparsky 2004). (3) Minimalist analysis of Accusative vs. Partitive case in Finnish (Borer 1998, 2005, Megerdoo- mian 2000, van Hout 2000, Ritter and Rosen 2000, Csirmaz 2002, Kratzer 2002, Svenonius 2002, Thomas 2003). a. Accusative is checked in AspP, a functional projection which induces telicity. b. Partitive is checked in a lower projection. • (1) rules out AspP for Finnish. (4) Position defended here (Kiparsky 1998): a. Accusative case is assigned to complements of BOUNDED (non-gradable) verbal pred- icates. b. Otherwise complements are assigned Partitive case. (5) Partitive case in Finnish: • a structural case (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001), • the default case of complements (Vainikka 1993, Anttila & Fong 2001), • syntactically alternates with Nominative, Genitive, and Accusative case. 1 • Following traditional grammar, we’ll treat Accusative as an abstract case that includes in addition to Accusative itself, the Accusative-like uses of Nominative and Genitive (for a different proposal, see Kiparsky 2001). -

New Latin Grammar

NEW LATIN GRAMMAR BY CHARLES E. BENNETT Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin in Cornell University Quicquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta Percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles: Omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat. —HORACE, Ars Poetica. COPYRIGHT, 1895; 1908; 1918 BY CHARLES E. BENNETT PREFACE. The present work is a revision of that published in 1908. No radical alterations have been introduced, although a number of minor changes will be noted. I have added an Introduction on the origin and development of the Latin language, which it is hoped will prove interesting and instructive to the more ambitious pupil. At the end of the book will be found an Index to the Sources of the Illustrative Examples cited in the Syntax. C.E.B. ITHACA, NEW YORK, May 4, 1918 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The present book is a revision of my Latin Grammar originally published in 1895. Wherever greater accuracy or precision of statement seemed possible, I have endeavored to secure this. The rules for syllable division have been changed and made to conform to the prevailing practice of the Romans themselves. In the Perfect Subjunctive Active, the endings -īs, -īmus, -ītis are now marked long. The theory of vowel length before the suffixes -gnus, -gna, -gnum, and also before j, has been discarded. In the Syntax I have recognized a special category of Ablative of Association, and have abandoned the original doctrine as to the force of tenses in the Prohibitive. Apart from the foregoing, only minor and unessential modifications have been introduced. In its main lines the work remains unchanged. -

On Uses of the Finnish Partitive Subject in Transitive Clauses Tuomas Huumo University of Turku, University of Tartu

Chapter 15 The partitive A: On uses of the Finnish partitive subject in transitive clauses Tuomas Huumo University of Turku, University of Tartu Finnish existential clauses are known for the case marking of their S arguments, which alternates between the nominative and the partitive. Existential S arguments introduce a discourse-new referent, and, if headed by a mass noun or a plural form, are marked with the partitive case that indicates non-exhaustive quantification (as in ‘There is some coffee inthe cup’). In the literature it has often been observed that the partitive is occasionally used even in transitive clauses to mark the A argument. In this work I analyze a hand-picked set of examples to explore this partitive A. I argue that the partitive A phrase often has an animate referent; that it is most felicitous in low-transitivity expressions where the O argument is likewise in the partitive (to indicate non-culminating aspect); that a partitive A phrase typically follows the verb, is in the plural and is typically modified by a quantifier (‘many’, ‘a lot of’). I then argue that the pervasiveness of quantifying expressions in partitive A phrases reflects a structural analogy with (pseudo)partitive constructions where a nominative head is followed by a partitive modifier (e.g. ‘a group of students’). Such analogies may be relevant in permitting the A function to be fulfilled by many kinds of quantifier + partitiveNPs. 1 Introduction The Finnish argument marking system is known for its extensive case alternation that concerns the marking of S (single arguments of intransitive predications) and O (object) arguments, as well as predicate adjectives. -

A First Book of Old English : Grammar, Reader, Notes, and Vocabulary

•' ""^••'"•^' ' LIBRARY Purchased bv Simdry Ftuad Vr/c 214635 3 A FIRST BOOK IN OLD ENGLISH GRAMMAR, READER, NOTES, AND FOCABULART BY ALBERT S. COOK PROFESSOR OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE IN YALE UNIVERSITY THIRD EDITION GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON ATLANTA • DALLAS • COLUMBUS • SAN FRANCISCO L 3 COPYRIGHT, 1894, 1903, 1921, BY ALBERT S. COOK ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 227.1 gfic gtbengam jgregg GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS • BOSTON U.S.A. TO JAMES MORGAN HART Author of "German Universities" and Scholar in Old English y PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. The present volume is an attempt to be of service to those who are beginning the study of our language, or who desire to acquaint themselves with a few speci- mens of our earliest literature. It has seemed to the author that there were two extremes to be avoided in its compilation — the treatment of Old English as though it consisted of wholly isolated phenomena, and the procedure upon a virtual assumption that the student was already acquainted with the cognate Germanic tongues and with the problems and methods of comparative phi- lology. The former treatment robs the study of its significance and value, which, like that of most other subjects, is found in its relations ; the latter repels and confounds the student at a stage when he is most in need of encouragement and attraction. How well the author has succeeded must be left to the judgment of others — the masters whom he follows at a distance, and the students whose interests he has constantly borne in mind. -

Structural Case in Finnish

Structural Case in Finnish Paul Kiparsky Stanford University 1 Introduction 1.1 Morphological case and abstract case The fundamental fact that any theory of case must address is that morphological form and syntactic function do not stand in a one-to-one correspondence, yet are systematically related.1 Theories of case differ in whether they define case categories at a single structural level of representation, or at two or more levels of representation. For theories of the first type, the mismatches raise a dilemma when morphological form and syntactic function diverge. Which one should the classification be based on? Generally, such single-level approaches determine the case inventory on the basis of morphology using paradigmatic contrast as the basic criterion, and propose rules or constraints that map the resulting cases to grammatical relations. Multi-level case theories deal with the mismatch between morphological form and syntactic function by distinguishing morphological case on the basis of form and abstract case on the basis of function. Approaches that distinguish between abstract case and morphological case in this way typically envisage an interface called “spellout” that determines the relationship between them. In practice, this outlook has served to legitimize a neglect of inflectional morphol- ogy. The neglect is understandable, for syntacticians’ interest in morphological case is naturally less as a system in its own right than as a diagnostic for ab- stract case and grammatical relations. But it is not entirely benign: compare the abundance of explicit proposals about how abstract cases are assigned with the minimal attention paid to how they are morphologically realized. -

Partitive-Accusative Alternations in Balto-Finnic Languages

Proceedings of the 2003 Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society 1 Partitive-Accusative Alternations in Balto-Finnic Languages AET LEES [email protected]. au 1. Introduction The present study looks at the case of direct objects of transitive verbs in the Balto-Finnic languages Estonian and Finnish, comparing the two languages. There are three structural or grammatical cases in Estonian: nominative, genitive and partitive. Finnish, in addition to these three, has a separate accusative case form, but only in the personal pronoun paradigm. All of these cases are used for direct objects, but they all, except the Finnish personal pronoun accusative, also have other uses. 2. Selection of object case Only clauses with active verbs have been considered in the present study. In all negative clauses the direct object is in the partitive case. In affirmative clauses, if the action is completed and the object is total, that is, the entire object is involved in the action, the case used is the accusative. The term ‘accusative’ is used as a blanket term for the non-partitive object case. In Estonian, more commonly than in Finnish, the completion of the event is indicated by an adverbial phrase or an oblique, indicating a change in position or state of the object. The total object is usually definite, or at least specific. If the action is not completed, or if it involves only part of the object, the partitive case is used. A partial object must be divisible, i.e. a mass noun or a plural count noun, but if the aspect is irresultative, the partitive object may be a singular count noun. -

Typology of Partitives Received October 28, 2019; Accepted November 17, 2020; Published Online February 18, 2021

Linguistics 2021; 59(4): 881–947 Ilja A. Seržant* Typology of partitives https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2020-0251 Received October 28, 2019; accepted November 17, 2020; published online February 18, 2021 Abstract: This paper explores the coding patterns of partitives and their functional extensions, based on a convenience sample of 138 languages from 46 families from all macroareas. Partitives are defined as constructions that may express the pro- portional relation of a subset to a superset (the true-partitive relation). First, it is demonstrated that, crosslinguistically, partitive constructions vary as to their syntactic properties and morphological marking. Syntactically, there is a cline from loose – possibly less grammaticalized – structures to partitives with rigid head-dependent relations and, finally, to morphologically integrated one-word partitives. Furthermore, partitives may be encoded NP-internally (mostly via an adposition) or pronominally. Morphologically, partitives primarily involve markers syncretic with separative, locative or possessive meanings. Finally, a number of languages employ no partitive marker at all. Secondly, these different strategies are not evenly distributed in the globe, with, for example, Eurasia being biased for the separative strategy. Thirdly, on the functional side, partitives may have functions in the following domains in addition to the true-partitive relation: plain quantification (pseudo-partitives), hypothetical events, predicate negation and aspectuality. I claim that the ability to encode plain quantification is the prerequisite for the other domains. Finally, it is argued that there is a universal preference towards syncretism of two semantically distinct concepts: the propor- tional, true-partitive relation (some of the books) and plain quantification (some books). -

Partitivity and Reference Boban Arsenijević, LUCL the Paper

Partitivity and reference Boban Arsenijevi, LUCL The paper presents the partitive phrase (PartP) as a part of the general functional sequence in the nominal domain. It is argued that PartP derives grammatical number and effects related to countability, defines units of division and introduces the potentials of indefinite, non-generic and non-mass reference. Identity is established between this functional projection and the projection that derives partitive constructions. Contents of SpecPartP are related with the structural representation of the lexical meaning of nominal expressions, in order to account for observations that there are two levels in the structure of nominal expressions at which countability is determined. 1. Introduction The term ‘partitive construction’ is traditionally used to refer to constructions of the type in (1) (e.g. Ladusaw 1982, De Hoop 1998). These are regularly non-definite (in the sense of Barwise and Cooper 1981) nominal expressions involving a complement with respect to which they establish a part-whole interpretation. This complement is realized as a PP (in English, headed by the preposition of) or as a nominal expression bearing a morphological case with partitive interpretation (partitive, genitive, dative). The precise interpretation of partitive constructions is that the denotation of the matrix NP is a part of the denotation of the nominal expression in the complement. A special property of this construction is that the nominal expression inside the complement has to be definite, and it is known, since Jackendoff 1977 and Selkirk 1977, as the ‘partitive constraint’. (1) a. One of the problems concerns heating. b. Seven of the ten students we met have blond hair.