Partitive Accomplishments Across Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is a Sample Copy, Not to Be Reproduced Or Sold

Startup Business Chinese: An Introductory Course for Professionals Textbook By Jane C. M. Kuo Cheng & Tsui Company, 2006 8.5 x 11, 390 pp. Paperback ISBN: 0887274749 Price: TBA THIS IS A SAMPLE COPY, NOT TO BE REPRODUCED OR SOLD This sample includes: Table of Contents; Preface; Introduction; Chapters 2 and 7 Please see Table of Contents for a listing of this book’s complete content. Please note that these pages are, as given, still in draft form, and are not meant to exactly reflect the final product. PUBLICATION DATE: September 2006 Workbook and audio CDs will also be available for this series. Samples of the Workbook will be available in August 2006. To purchase a copy of this book, please visit www.cheng-tsui.com. To request an exam copy of this book, please write [email protected]. Contents Tables and Figures xi Preface xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction to the Chinese Language xvi Introduction to Numbers in Chinese xl Useful Expressions xlii List of Abbreviations xliv Unit 1 问好 Wènhǎo Greetings 1 Unit 1.1 Exchanging Names 2 Unit 1.2 Exchanging Greetings 11 Unit 2 介绍 Jièshào Introductions 23 Unit 2.1 Meeting the Company Manager 24 Unit 2.2 Getting to Know the Company Staff 34 Unit 3 家庭 Jiātíng Family 49 Unit 3.1 Marital Status and Family 50 Unit 3.2 Family Members and Relatives 64 Unit 4 公司 Gōngsī The Company 71 Unit 4.1 Company Type 72 Unit 4.2 Company Size 79 Unit 5 询问 Xúnwèn Inquiries 89 Unit 5.1 Inquiring about Someone’s Whereabouts 90 Unit 5.2 Inquiring after Someone’s Profession 101 Startup Business Chinese vii Unit -

(Marco) Nie Ing, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA

Address: Department of Civil and Environmental Engineer- Yu (Marco) Nie ing, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA. Curriculum Vitae Phone: +1 847-467-0502 Email: [email protected] October 2018 WWW: http://www.mccormick.northwestern.edu/research- faculty/directory/profiles/nie-yu.html Appointments 2017 - present Professor Civil and Environmental Engineering, Northwestern University, affiliated with Northwestern University Transportation Center 2012 - 2017 Associate Professor Civil and Environmental Engineering, Northwestern University, affiliated with Northwestern University Transportation Center 2015 - present Adjunct Professor School of Transportation and Logistics, Southwestern Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China 2006 - 2012 Assistant Professor Civil and Environmental Engineering, Northwestern University, affiliated with Northwestern University Transportation Center Education and Qualifications 1999 B.Sc.(Hons) Tsinghua University Civil Engineering 2001 M.Eng. National University of Singapore Civil and Environmental Engineering 2006 Ph.D. University of California, Davis Civil and Environmental Engineering Honors and Awards 2018 Stella Dafermos Best Paper Award TRB Transportation Network Mod- eling Committee 2006 -2009 Louis Berger Junior Chair Northwestern University 2007-2008 Searle Junior Faculty Fellow Northwestern University 2003-2004 John Muir Fellowship University of California, Davis 1999 Outstanding Student Award Tsinghua University 1998 United Technology RongHong Scholarship Tsinghua University Publications By October 2018, I have authored or co-authored 78 articles in peer-reviewed journals, including 28 in Transportation Research Part B, 3 in Transportation Science. My H-Index is 23 according to Scopus 1 and 30 according to Google Scholar. Refereed articles 1. Chen, P. and Y. M. Nie (2018). Optimal Design of Demand Adaptive Paired-Line Hybrid Transit: Case of Radial Route Structure. Transportation Research Part E 110, 71–89. -

Effect of Trace Rare Earth Element Er on Al-Zn-Mg Alloy

Effect of trace rare earth element Er on Al-Zn-Mg alloy XU Guo-fu(徐国富)1, MOU Shen-zhou(牟申周)1, YANG Jun-jun(杨军军)2, JIN Tou-nan(金头男)3, NIE Zuo-ren(聂祚仁)3, YIN Zhi-min(尹志民)1 1. School of Materials Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China; 2. Ltd AT&M, Central Iron & Steel Research Institute, Beijing 100039, China; 3. School of Materials Science and Engineering, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing 100022, China Received 24 January 2006; accepted 26 April 2006 Abstract: Al-6Zn-2Mg and Al-6Zn-2Mg-0.4Er alloys were prepared by cast metallurgy. The effects of trace Er on the mechanical properties, recrystallization behavior and age-hardening characteristic of Al-Zn-Mg alloy were studied. The effect of Er on microstructures was also studied by OM, XRD, SEM, EDS and TEM. The results show that the addition of Er on Al-6Zn-2Mg alloy is capable of refining grains obviously. The addition of Er can improve the strength considerably by strengthening mechanisms of precipitation and grain refinement. With the addition of Er into Al-6Zn-2Mg alloy, the aging process is quickened and the age-hardening effect is heightened. Er additive can retard the recrystallizing behavior of Al-6Zn-2Mg alloy and cause the increase of recrystallization temperature due to the pinning effect of fine dispersed Al3Er precipitates on dislocations and subgrain boundaries. Key words: erbium(Er); Al-Zn-Mg alloy; Al3Er; precipitation strengthening; fine grain strengthening; mechanical properties; recrystallization 1 Introduction 2 Experimental Remarkable effects of rear-earth elements on The alloys are prepared by cast metallurgy with aluminium alloys, such as eliminating impurities, high purity aluminium (99.99%), industrially pure zinc purifying melt, refining as-cast structure, retarding (99.9%), industrially pure magnesium (99.9%), and recrystallization and refining precipitated phases, have master alloy Al-6.2Er. -

Jingjiao Under the Lenses of Chinese Political Theology

religions Article Jingjiao under the Lenses of Chinese Political Theology Chin Ken-pa Department of Philosophy, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City 24205, Taiwan; [email protected] Received: 28 May 2019; Accepted: 16 September 2019; Published: 26 September 2019 Abstract: Conflict between religion and state politics is a persistent phenomenon in human history. Hence it is not surprising that the propagation of Christianity often faces the challenge of “political theology”. When the Church of the East monk Aluoben reached China in 635 during the reign of Emperor Tang Taizong, he received the favorable invitation of the emperor to translate Christian sacred texts for the collections of Tang Imperial Library. This marks the beginning of Jingjiao (oY) mission in China. In historiographical sense, China has always been a political domineering society where the role of religion is subservient and secondary. A school of scholarship in Jingjiao studies holds that the fall of Jingjiao in China is the obvious result of its over-involvement in local politics. The flaw of such an assumption is the overlooking of the fact that in the Tang context, it is impossible for any religious establishments to avoid getting in touch with the Tang government. In the light of this notion, this article attempts to approach this issue from the perspective of “political theology” and argues that instead of over-involvement, it is rather the clashing of “ideologies” between the Jingjiao establishment and the ever-changing Tang court’s policies towards foreigners and religious bodies that caused the downfall of Jingjiao Christianity in China. This article will posit its argument based on the analysis of the Chinese Jingjiao canonical texts, especially the Xian Stele, and takes this as a point of departure to observe the political dynamics between Jingjiao and Tang court. -

Gateless Gate Has Become Common in English, Some Have Criticized This Translation As Unfaithful to the Original

Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Original Collection in Chinese by Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Page ii Frontspiece “Wú Mén Guān” Facsimile of the Original Cover Page iii Page iv Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Sixth Edition Before Thought Publications Huntington Beach, CA 2010 Page v BEFORE THOUGHT PUBLICATIONS HUNTINGTON BEACH, CA 92648 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2010 ENGLISH VERSION BY PAUL LYNCH, JDPSN NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC, OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT THE PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY LULU INCORPORATION, MORRISVILLE, NC, USA COVER PRINTED ON LAMINATED 100# ULTRA GLOSS COVER STOCK, DIGITAL COLOR SILK - C2S, 90 BRIGHT BOOK CONTENT PRINTED ON 24/60# CREAM TEXT, 90 GSM PAPER, USING 12 PT. GARAMOND FONT Page vi Dedication What are we in this cosmos? This ineffable question has haunted us since Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree. I would like to gracefully thank the author, Chán Master Wúmén, for his grace and kindness by leaving us these wonderful teachings. I would also like to thank Chán Master Dàhuì for his ineptness in destroying all copies of this book; thankfully, Master Dàhuì missed a few so that now we can explore the teachings of his teacher. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

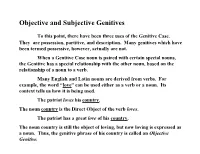

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Pragmatic Analysis of English Fuzzy Language in International Business Negotiation Ling-Ling ZUO and Ying HE Ningbo Dahongying University, Ningbo, China

2016 International Conference on Education, Training and Management Innovation (ETMI 2016) ISBN: 978-1-60595-395-3 Pragmatic Analysis of English Fuzzy Language in International Business Negotiation Ling-ling ZUO and Ying HE Ningbo Dahongying University, Ningbo, China Keywords: International business negotiation, Fuzzy language, Pragmatic analysis. Abstract. This thesis aims to lead negotiators to pay more attention to use fuzzy language and put forward three strategies for negotiators to use fuzzy language in business negotiation following the cooperative principle and politeness principle. The thesis proves its importance in business negotiation by theoretical analysis and showing a series of examples. The author provides some strategies for negotiators and guides them to negotiate in international business negotiation well such as ambiguity, euphemism and so on. Sometimes, negotiators have to violate the maxims to gain a better result. The appropriate appliance of fuzzy language can relive the tension in business negotiation, being accurate and flexible, and improving the efficiency. The innovation of this paper is from the practical application of fuzzy language to better negotiation. Introduction Nowadays, with the development of economy, the communication between countries becomes closer and closer. The foreign trades are becoming more and more frequent. In order to integrate into the globalization quickly, people must pay attention to international business negotiation in the foreign trade. Business negotiation is a basic form of communication, which plays an important role in the foreign trade. Business negotiation requires negotiators not only know the rules, laws and foreign trade business very well, but also have negotiation skills. However, in real business negotiations, accurate and clear information may put one party in a worse situation. -

The Anonymity Heuristic: How Surnames Stop Identifying People When They Become Trademarks

Volume 124 Issue 2 Winter 2019 The Anonymity Heuristic: How Surnames Stop Identifying People When They Become Trademarks Russell W. Jacobs Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlr Part of the Behavioral Economics Commons, Civil Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Economic Theory Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, Legislation Commons, Other Law Commons, Phonetics and Phonology Commons, Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, Psycholinguistics and Neurolinguistics Commons, and the Semantics and Pragmatics Commons Recommended Citation Russell W. Jacobs, The Anonymity Heuristic: How Surnames Stop Identifying People When They Become Trademarks, 124 DICK. L. REV. 319 (2020). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlr/vol124/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\D\DIK\124-2\DIK202.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-JAN-20 14:56 The Anonymity Heuristic: How Surnames Stop Identifying People When They Become Trademarks Russell Jacobs ABSTRACT This Article explores the following question central to trade- mark law: if a homograph has both a surname and a trademark interpretation will consumers consider those interpretations as intrinsically overlapping or the surname and trademark as com- pletely separate and unrelated words? While trademark jurispru- dence typically has approached this question from a legal perspective or with assumptions about consumer behavior, this Article builds on the Law and Behavioral Science approach to legal scholarship by drawing from the fields of psychology, lin- guistics, economics, anthropology, sociology, and marketing. -

Additional Reviewers

Additional Reviewers Rehab AbdelKader Wei Huang Jaidev Patwardhan Aneesh Aggarwal Yehea Ismail Marinus Pennings Raid Ayoub Hans Jacobson Antoniu Pop Saisanthosh Balakrishnan Renatas Jakushokas Mikhail Popovich Rajeev Balasubramonian Geert Janssen Prateek Pujara Deniz Balkan Kamil Kedziersky Fahim Rahim Chinnakrishnan Ballapuram Georgios Keramidas Wenjing Rao Ansuman Banerjee E.J. Kim Vimal Reddy Bradford Beckmann Youngmin Kim Samuel Rodriguez Gordon Bell Jingfei Kong Bogdan Romanescu Luca Benini Gurhan Kucuk Eric Rotenberg Sergey Berezin Prasad Kulkarni Barry Rountree Reinaldo Bergamaschi Christopher L. LaFrieda Silvius Rus Jannick Bergeron Johnny LeBlanc Babak Salamat Santosh Biswas Han-Lin Lee Peter Sassone Steven Burns Leonard Lee Jun Sawada Carlos A. Cabrera Wan-Ping Lee Martin Schulz Zhongbo Cao Bing Li Li Shang Guangyu Chen Tong Li Shervin Sharifi MingJing Chen Chun-Shan Lin Joseph Sharkey Tai-Chen Chen Yan Lin Montek Singh Tung-Chieh Chen Hung-Yi Liu Abhishek Somani Yi-Zong Chen Dan Lo Srikanth Srinivasan Allen C. Cheng Jiang Long Witawas Srisa-an Lei Cheng David Lowenthal Ankur Srivastava Eli Chiprout Shih-Lien Lu Christian Stangier John Chu Anita Lungu Nathan Thomas Martin Dimitrov Tony Ma Carlos Tokunaga Praveen Dua Yi Ma Nuengwong Tuaycharoen Lieven Eeckhout Francisco J. Martinez Ankush Varma Natalie Enright-Jerger Sally A. McKee Pavlos Vranas Joshua B. Fryman Albert Meixner Sarma Vrudhula Zhaohui Fu Gokhan Memik Markus Wedler Amit Gandhi Ke Meng Eric Weglarz Hongliang Gao Fayez Mohamood Paul West Michael Geiger Kartik Mohanram Polychronis Xekalakis Steven German In-Ho Moon Hua Xiang Mrinmoy Ghosh Kevin Moore Chengmo Yang Jim Grundy Miquel Moretó Matt Yourst Onur Guzey Sangeetha Nair Hui Zeng Kevin S. -

Finnish Partitive Case As a Determiner Suffix

Finnish partitive case as a determiner suffix Problem: Finnish partitive case shows up on subject and object nouns, alternating with nominative and accusative respectively, where the interpretation involves indefiniteness or negation (Karlsson 1999). On these grounds some researchers have proposed that partitive is a structural case in Finnish (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001). A problematic consequence of this is that Finnish is assumed to have a structural case not found in other languages, losing the universal inventory of structural cases. I will propose an alternative, namely that partitive be analysed instead as a member of the Finnish determiner class. Data: There are three contexts in which the Finnish subject is in the partitive (alternating with the nominative in complementary contexts): (i) indefinite divisible non-count nouns (1), (ii) indefinite plural count nouns (2), (iii) where the existence of the argument is completely negated (3). The data are drawn from Karlsson (1999:82-5). (1) Divisible non-count nouns a. Partitive mass noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative mass noun = def Purki-ssa on leipä-ä. Leipä on purki-ssa. tin-INESS is bread-PART Bread is tin-INESS ‘There is some bread in the tin.’ ‘The bread is in the tin.’ (2) Plural count nouns a. Partitive count noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative count noun = def Kadu-lla on auto-j-a. Auto-t ovat kadulla. Street-ADESS is.3SG car-PL-PART Car-PL are.3PL street-ADESS ‘There are cars in the street.’ ‘The cars are in the street.’ (3) Negation a. Partitive, negation of existence b. c.f. -

Video Recovery Via Learning Variation and Consistency of Images

Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-17) Video Recovery via Learning Variation and Consistency of Images Zhouyuan Huo,1 Shangqian Gao,2 Weidong Cai,3 Heng Huang1∗ 1Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Texas at Arlington, USA 2College of Engineering, Northeastern University, USA 3School of Information Technologies, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract 2010). However, trace norm is not the best approximation for rank minimization regularization. If a non-zero singular Matrix completion algorithms have been popularly used to recover images with missing entries, and they are proved value of a matrix varies, the trace norm value will change si- to be very effective. Recent works utilized tensor comple- multaneously, but the rank of the matrix keeps constant. So, tion models in video recovery assuming that all video frames there is a big gap between trace norm and rank minimiza- are homogeneous and correlated. However, real videos are tion, and a better model to approximate rank minimization made up of different episodes or scenes, i.e. heterogeneous. regularization is desired for learning a low-rank structure. Therefore, a video recovery model which utilizes both video In a recent work (Liu et al. 2009), Liu applied low-rank spatiotemporal consistency and variation is necessary. To model to solve image recovery problem. He assumed that solve this problem, we propose a new video recovery method video is in low-rank structure, however, videos are not ho- Sectional Trace Norm with Variation and Consistency Con- mogeneous, and they may contain sequences of images from straints (STN-VCC).