Partitive Case and Aspect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Strategy of Case-Marking

Case marking strategies Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov1 Radboud University Nijmegen DRAFT January 2006 Abstract Two strategies of case marking in natural languages are discussed. These are defined as two violable constraints whose effects are shown to converge in the case of differential object marking but diverge in the case of differential subject marking. The strength of the case bearing arguments will be shown to be of utmost importance for case marking as well as voice alternations. The strength of arguments can be viewed as a function of their discourse prominence. The analysis of the case marking patterns we find cross-linguistically is couched in a bidirectional OT analysis. 1. Assumptions In this section we wish to put forward our three basic assumptions: (1) In ergative-absolutive systems ergative case is assigned to the first argument x of a two-place relation R(x,y). (2) In nominative-accusative systems accusative case is assigned to the second argument y of a two-place relation R(x,y). (3) Morphologically unmarked case can be the absence of case. The first two assumptions deal with the linking between the first (highest) and second (lowest) argument in a transitive sentence and the type of case marking. For reasons of convenience, we will refer to these arguments quite sloppily as the subject and the object respectively, although we are aware of the fact that the labels subject and object may not be appropriate in all contexts, dependent on how they are actually defined. In many languages, ergative and accusative case are assigned only or mainly in transitive sentences, while in intransitive sentences ergative and accusative case are usually not assigned. -

Sinitic Languages of Northwest China: Where Did Their Case Marking Come From?* Dan Xu

Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?* Dan Xu To cite this version: Dan Xu. Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?*. Cao, Djamouri and Peyraube. Languages in contact in Northwestern China, 2015. hal-01386250 HAL Id: hal-01386250 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01386250 Submitted on 31 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?* XU DAN 1. Introduction In the early 1950s, Weinreich (1953) published a monograph on language contact. Although this subject drew the attention of a few scholars, at the time it remained marginal. Over two decades, several scholars including Moravcsik (1978), Thomason and Kaufman (1988), Aikhenvald (2002), Johanson (2002), Heine and Kuteva (2005) and others began to pay more attention to language contact. As Thomason and Kaufman (1988: 23) pointed out, language is a system, or even a system of systems. Perhaps this is why previous studies (Sapir, 1921: 203; Meillet 1921: 87) indicated that grammatical categories are not easily borrowed, since grammar is a system. -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

Estonian Transitive Verb Classes, Object Case, and Progressive1 Anne Tamm Research Institute for Linguistics, Budapest

Estonian transitive verb classes, object case, and progressive1 Anne Tamm Research Institute for Linguistics, Budapest 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to show the relation between aspect and object case in Estonian and to establish a verb classification that is predictive of object case behavior. Estonian sources disagree on the nature of the grounds for an aspectual verb classification and, therefore, on the exact verbal classes. However, the morphological genitive and nominative case marking as opposed to the morphological partitive case marking of Estonian objects is uniformly seen as an important indicator for an aspectual verb class membership. In addition, object case alternation reflects the aspectual oppositions of perfectivity and imperfectivity that cannot be accounted for by verbal lexical aspect only. This article spells out these aspectual phenomena, relating them to a verb classification. The verb classes are distinguished from each other according to the nature of the situations or events they typically describe. The verb classification is established on the basis of tests that involve only the partitive object case. These tests use the phenomena related to progressive in Estonian. 2. A note on terminology Several accounts of aspectuality view a sentence’s aspectual properties as being determined by more components in a sentence than just the verb alone. More specifically, two temporal factors of situations or aspectuality are distinguished: on the one hand, boundedness, viewpoint, or perfectivity and, on the other hand, situation, event structure or telicity (Smith 1990, Verkuyl 1989, Depraetere 1995). Authors such as Verkuyl (1989) distinguish syntactically two distinct levels of aspectuality. The VP aspectual level, that is, the aspectual phenomena at the level of the verb and its complements, is referred to as telicity, VP- terminativity, or event structure. -

The Case of Restricted Locatives Ora Matushansky

The case of restricted locatives Ora Matushansky To cite this version: Ora Matushansky. The case of restricted locatives. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung , 2019, 23 (2), 10.18148/sub/2019.v23i2.604. halshs-02431372 HAL Id: halshs-02431372 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02431372 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The case of restricted locatives1 Ora MATUSHANSKY — SFL (CNRS/Université Paris-8)/UiL OTS/Utrecht University Abstract. This paper examines the cross-linguistic phenomenon of locative case restricted to a closed class of items (L-nouns). Starting with Latin, I suggest that the restriction is semantic in nature: L-nouns denote in the spatial domain and hence can be used as locatives without further material. I show how the independently motivated hypothesis that directional PPs consist of two layers, Path and Place, explains the directional uses of L-nouns and the cases that are assigned then, and locate the source of the locative case itself in p0, for which I then provide a clear semantic contribution: a type-shift from the domain of loci to the object domain. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

How Do Young Children Acquire Case Marking?

INVESTIGATING FINNISH-SPEAKING CHILDREN’S NOUN MORPHOLOGY: HOW DO YOUNG CHILDREN ACQUIRE CASE MARKING? Thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences 2015 HENNA PAULIINA LEMETYINEN SCHOOL OF PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCES 2 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. 8 DECLARATION .......................................................................................................................... 9 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT .......................................................................................................... 9 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: General introduction to language acquisition research ...................................... 11 1.1. Generativist approaches to child language............................................................ 11 1.2. Usage-based approaches to child language........................................................... 14 1.3. The acquisition of morphology ............................................................................. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

PARASITIC MIRATIVITY of ENGLISH USE in COLIN TREVORROWS MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Th

PARASITIC MIRATIVITY OF ENGLISH USE IN COLIN TREVORROWS MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By MUJI RETNO Reg. No. 40300111080 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2016 PARASITIC MIRATIVITY OF ENGLISH USE IN COLIN TREVORROW’S MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By MUJI RETNO Reg. No. 40300111080 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2016 i MOTTO “EDUCATION IS WHAT REMAINS AFTER ONE HAS FORGOTTEN WHAT ONE HAS LEARNED IN SCHOOL.” (Albert Eistein) “EDUCATION IS A PROGRESSIVE DISCOVERY OF OUR OWN IGNORENCE.” (Charlie Chaplin) “EVERY THE LAST STEP INEVITABLY HAS THE FIRST STEP” (Muji Retno) ii ACKNOWLEDGE All praises to Allah who has blessed, guided and given the health to the researcherduring writing this thesis. Then, the researcherr would like to send invocation and peace to Prophet Muhammad SAW peace be upon him, who has guided the people from the bad condition to the better life. The researcher realizes that in writing and finishing this thesis, there are many people that have provided their suggestion, advice, help and motivation. Therefore, the researcher would like to express thanks and highest appreciation to all of them. For the first, the researcher gives special gratitude to her parents, Masir Hadis and Jumariah Yaha who have given their loves, cares, supports and prayers in every single time. -

Prior Linguistic Knowledge Matters : the Use of the Partitive Case In

B 111 OULU 2013 B 111 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O.B. 7500 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA SERIES EDITORS HUMANIORAB Marianne Spoelman ASCIENTIAE RERUM NATURALIUM Marianne Spoelman Senior Assistant Jorma Arhippainen PRIOR LINGUISTIC BHUMANIORA KNOWLEDGE MATTERS University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen CTECHNICA THE USE OF THE PARTITIVE CASE IN FINNISH Docent Hannu Heusala LEARNER LANGUAGE DMEDICA Professor Olli Vuolteenaho ESCIENTIAE RERUM SOCIALIUM University Lecturer Hannu Heikkinen FSCRIPTA ACADEMICA Director Sinikka Eskelinen GOECONOMICA Professor Jari Juga EDITOR IN CHIEF Professor Olli Vuolteenaho PUBLICATIONS EDITOR Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FINNISH LANGUAGE ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Print) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS B Humaniora 111 MARIANNE SPOELMAN PRIOR LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE MATTERS The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Human Sciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in Keckmaninsali (Auditorium HU106), Linnanmaa, on 24 May 2013, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2013 Copyright © 2013 Acta Univ. Oul. B 111, 2013 Supervised by Docent Jarmo H. Jantunen Professor Helena Sulkala Reviewed by Professor Tuomas Huumo Associate Professor Scott Jarvis Opponent Associate Professor Scott Jarvis ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Printed) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2013 Spoelman, Marianne, Prior linguistic knowledge matters: The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Humanities, Finnish Language, P.O. -

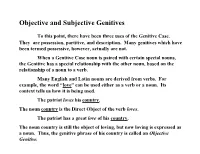

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium.