On the Morpho-Syntax of Possessive Constructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

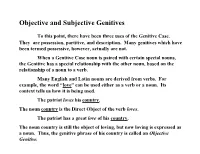

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Finnish Partitive Case As a Determiner Suffix

Finnish partitive case as a determiner suffix Problem: Finnish partitive case shows up on subject and object nouns, alternating with nominative and accusative respectively, where the interpretation involves indefiniteness or negation (Karlsson 1999). On these grounds some researchers have proposed that partitive is a structural case in Finnish (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001). A problematic consequence of this is that Finnish is assumed to have a structural case not found in other languages, losing the universal inventory of structural cases. I will propose an alternative, namely that partitive be analysed instead as a member of the Finnish determiner class. Data: There are three contexts in which the Finnish subject is in the partitive (alternating with the nominative in complementary contexts): (i) indefinite divisible non-count nouns (1), (ii) indefinite plural count nouns (2), (iii) where the existence of the argument is completely negated (3). The data are drawn from Karlsson (1999:82-5). (1) Divisible non-count nouns a. Partitive mass noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative mass noun = def Purki-ssa on leipä-ä. Leipä on purki-ssa. tin-INESS is bread-PART Bread is tin-INESS ‘There is some bread in the tin.’ ‘The bread is in the tin.’ (2) Plural count nouns a. Partitive count noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative count noun = def Kadu-lla on auto-j-a. Auto-t ovat kadulla. Street-ADESS is.3SG car-PL-PART Car-PL are.3PL street-ADESS ‘There are cars in the street.’ ‘The cars are in the street.’ (3) Negation a. Partitive, negation of existence b. c.f. -

Department of English and American Studies Possessive Pronouns in English and Czech Works of Fiction, Their Use with Parts of Hu

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Kristýna Onderková Possessive Pronouns in English and Czech Works of Fiction, Their Use with Parts of Human Body and Translation Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Ing. Mgr. Jiří Rambousek 2009 0 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………… 1 I would like to express thanks to my supervisor, Ing. Mgr. Jiří Rambousek, for his valuable advice. 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................... 5 2 Theory.............................................................................................................................. 7 2.1 English possessive pronouns.......................................................................... 7 2.1.1 Grammatical properties................................................................... 7 2.1.2 Use...................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Czech possessive pronouns............................................................................. 9 2.2.1 Grammatical properties................................................................... 10 2.2.2 Use...................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Translating possessive pronouns................................................................... -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayerau Osijeku Filozofskifakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Pedagogije Anja Kolobarić A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations Završni rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc Gabrijela Buljan Osijek, 2014. Summary This research paper explores partitive expressions not only as devices that impose countable readings in uncountable nouns, but also as a means of directing the interpretive focus on different aspects of the uncountable entities denoted by nouns. This exploration was made possible through a close examination of specific grammar books, but also through a small-scale corpus study we have conducted. We first explain the theory behind uncountable nouns and partitive expressions, and then present the results of our corpus study, demonstrating thereby the creative nature of the English language. We also propose some cautious generalizations concerning the distribution of partitive expressions within the analyzed semantic domains. Key words: noncount noun, concrete noun, partitive expression, corpus data, data analysis 2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 4 2. Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 Distinction between Count and Noncount -

The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish

Absolutely a Matter of Degree: The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish Paul Kiparsky CLS, April 2005 1. Functional categories (1) What are the functional categories of a language? A proposal. a. Syntax: functional categories are projected by functional heads. b. Morphology: functional categories are assigned by affixes or inherently marked on lexical items. c. Null elements may mark default values in paradigmatic system of functional categories. d. Otherwise functional categories are not specified. (2) a. Diachronic evidence: syntactic projections of functional categories emerge hand in hand with lexical heads (e.g. Kiparsky 1996, 1997 on English, Condoravdi and Kiparsky 2002, 2004 on Greek.) b. Empirical arguments from morphology (e.g. Kiparsky 2004). (3) Minimalist analysis of Accusative vs. Partitive case in Finnish (Borer 1998, 2005, Megerdoo- mian 2000, van Hout 2000, Ritter and Rosen 2000, Csirmaz 2002, Kratzer 2002, Svenonius 2002, Thomas 2003). a. Accusative is checked in AspP, a functional projection which induces telicity. b. Partitive is checked in a lower projection. • (1) rules out AspP for Finnish. (4) Position defended here (Kiparsky 1998): a. Accusative case is assigned to complements of BOUNDED (non-gradable) verbal pred- icates. b. Otherwise complements are assigned Partitive case. (5) Partitive case in Finnish: • a structural case (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001), • the default case of complements (Vainikka 1993, Anttila & Fong 2001), • syntactically alternates with Nominative, Genitive, and Accusative case. 1 • Following traditional grammar, we’ll treat Accusative as an abstract case that includes in addition to Accusative itself, the Accusative-like uses of Nominative and Genitive (for a different proposal, see Kiparsky 2001). -

New Latin Grammar

NEW LATIN GRAMMAR BY CHARLES E. BENNETT Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin in Cornell University Quicquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta Percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles: Omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat. —HORACE, Ars Poetica. COPYRIGHT, 1895; 1908; 1918 BY CHARLES E. BENNETT PREFACE. The present work is a revision of that published in 1908. No radical alterations have been introduced, although a number of minor changes will be noted. I have added an Introduction on the origin and development of the Latin language, which it is hoped will prove interesting and instructive to the more ambitious pupil. At the end of the book will be found an Index to the Sources of the Illustrative Examples cited in the Syntax. C.E.B. ITHACA, NEW YORK, May 4, 1918 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The present book is a revision of my Latin Grammar originally published in 1895. Wherever greater accuracy or precision of statement seemed possible, I have endeavored to secure this. The rules for syllable division have been changed and made to conform to the prevailing practice of the Romans themselves. In the Perfect Subjunctive Active, the endings -īs, -īmus, -ītis are now marked long. The theory of vowel length before the suffixes -gnus, -gna, -gnum, and also before j, has been discarded. In the Syntax I have recognized a special category of Ablative of Association, and have abandoned the original doctrine as to the force of tenses in the Prohibitive. Apart from the foregoing, only minor and unessential modifications have been introduced. In its main lines the work remains unchanged. -

A Morphological Comparative Study Between Albanian and English Language

European Scientific Journal A morphological comparative study between Albanian and English language Aida Kurani Anita Muho University “Aleksander Moisiu”, Durres, Albania Abstract: The aim of this study is to point out similarities and differences of English and Albanian language in the morphological level, trying to compare different parts of speech of both languages. Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs or adjectives and names etc, i.e. the Albanian language differs in terms of gender and plural adjectives, while English has not such a feature. Therefore formal distinctions between parts of speech should be done within the framework of a given language and should not be applied in other languages .In this study we have analyzed nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjective structures, the use of articles, pronouns etc. in Albanian and English. In the light of modern linguistics, comparative method plays an important role in the acquisition of languages comparing the first language with the target language. Comparative method is also considered as a key factor in the scientific research of modern linguistics, so it can be used successfully in teaching. Keywords; Albanian, English, differences, morphology, similarities, teaching. 28 European Scientific Journal Introduction In Albanian language, the comparative studies in linguistics are very rare. Considering the fact that language is closely related to culture, a linguistic comparative study is also a cultural comparison. Although all languages mainly play a similar role, there are similarities and differences between them. Knowing the differences between the two languages also helps in identifying students' linguistic errors in the process of teaching the grammar. -

On Uses of the Finnish Partitive Subject in Transitive Clauses Tuomas Huumo University of Turku, University of Tartu

Chapter 15 The partitive A: On uses of the Finnish partitive subject in transitive clauses Tuomas Huumo University of Turku, University of Tartu Finnish existential clauses are known for the case marking of their S arguments, which alternates between the nominative and the partitive. Existential S arguments introduce a discourse-new referent, and, if headed by a mass noun or a plural form, are marked with the partitive case that indicates non-exhaustive quantification (as in ‘There is some coffee inthe cup’). In the literature it has often been observed that the partitive is occasionally used even in transitive clauses to mark the A argument. In this work I analyze a hand-picked set of examples to explore this partitive A. I argue that the partitive A phrase often has an animate referent; that it is most felicitous in low-transitivity expressions where the O argument is likewise in the partitive (to indicate non-culminating aspect); that a partitive A phrase typically follows the verb, is in the plural and is typically modified by a quantifier (‘many’, ‘a lot of’). I then argue that the pervasiveness of quantifying expressions in partitive A phrases reflects a structural analogy with (pseudo)partitive constructions where a nominative head is followed by a partitive modifier (e.g. ‘a group of students’). Such analogies may be relevant in permitting the A function to be fulfilled by many kinds of quantifier + partitiveNPs. 1 Introduction The Finnish argument marking system is known for its extensive case alternation that concerns the marking of S (single arguments of intransitive predications) and O (object) arguments, as well as predicate adjectives. -

Errors in Applying Rules for English Possessive Case.The Case of 3

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Mentouri University Constantine Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of Languages Errors in Applying Rules for English Possessive Case.The Case of 3rd Year Students, Constantine. Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master Degree in Applied Language Studies Submitted By Supervisor Lemtaiche Sabrina Dr. Belouahem Riad Academic Year: 2009/2010 Dedication “Yesterday is a history, tomorrow is a mystery, today is a gift that is why we call it the present.” To : My beloved family; my father and my mother. My brother and my sisters. To: My best friends. i Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my greatest gratitude to Allah the almighty for the completion of my study. In this opportunity, I would like to express my gratitude to the people who helped me finishing my final project. My greatest gratitude goes to: Dr. Belouhem Riad, my supervisor, for his patience in providing continuous and careful guidance as well as encouragement, indispensible suggestion and advice. Dr. Ahmed Sid haoues who has permitted me to conduct the test in his class. My beloved family and my best friends who always give their love, care, and support me to finish my project. Finally, I realize that the study is still far from perfect; I have great expectation that this final project would be useful for further study. ii Abstract This project aims mainly at determining the main errors and finding out the causes or sources of the errors in using English possessive case markers by 3rd year university learners at the English Department, Mentouri University, Constantine.