The Case of the Object in Early Estonian and Finnish Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Strategy of Case-Marking

Case marking strategies Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov1 Radboud University Nijmegen DRAFT January 2006 Abstract Two strategies of case marking in natural languages are discussed. These are defined as two violable constraints whose effects are shown to converge in the case of differential object marking but diverge in the case of differential subject marking. The strength of the case bearing arguments will be shown to be of utmost importance for case marking as well as voice alternations. The strength of arguments can be viewed as a function of their discourse prominence. The analysis of the case marking patterns we find cross-linguistically is couched in a bidirectional OT analysis. 1. Assumptions In this section we wish to put forward our three basic assumptions: (1) In ergative-absolutive systems ergative case is assigned to the first argument x of a two-place relation R(x,y). (2) In nominative-accusative systems accusative case is assigned to the second argument y of a two-place relation R(x,y). (3) Morphologically unmarked case can be the absence of case. The first two assumptions deal with the linking between the first (highest) and second (lowest) argument in a transitive sentence and the type of case marking. For reasons of convenience, we will refer to these arguments quite sloppily as the subject and the object respectively, although we are aware of the fact that the labels subject and object may not be appropriate in all contexts, dependent on how they are actually defined. In many languages, ergative and accusative case are assigned only or mainly in transitive sentences, while in intransitive sentences ergative and accusative case are usually not assigned. -

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

Estonian Transitive Verb Classes, Object Case, and Progressive1 Anne Tamm Research Institute for Linguistics, Budapest

Estonian transitive verb classes, object case, and progressive1 Anne Tamm Research Institute for Linguistics, Budapest 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to show the relation between aspect and object case in Estonian and to establish a verb classification that is predictive of object case behavior. Estonian sources disagree on the nature of the grounds for an aspectual verb classification and, therefore, on the exact verbal classes. However, the morphological genitive and nominative case marking as opposed to the morphological partitive case marking of Estonian objects is uniformly seen as an important indicator for an aspectual verb class membership. In addition, object case alternation reflects the aspectual oppositions of perfectivity and imperfectivity that cannot be accounted for by verbal lexical aspect only. This article spells out these aspectual phenomena, relating them to a verb classification. The verb classes are distinguished from each other according to the nature of the situations or events they typically describe. The verb classification is established on the basis of tests that involve only the partitive object case. These tests use the phenomena related to progressive in Estonian. 2. A note on terminology Several accounts of aspectuality view a sentence’s aspectual properties as being determined by more components in a sentence than just the verb alone. More specifically, two temporal factors of situations or aspectuality are distinguished: on the one hand, boundedness, viewpoint, or perfectivity and, on the other hand, situation, event structure or telicity (Smith 1990, Verkuyl 1989, Depraetere 1995). Authors such as Verkuyl (1989) distinguish syntactically two distinct levels of aspectuality. The VP aspectual level, that is, the aspectual phenomena at the level of the verb and its complements, is referred to as telicity, VP- terminativity, or event structure. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

The Accusative Case the Accusative Case Is Applied to the Direct Object of the Verb

The Accusative Case The accusative case is applied to the direct object of the verb. For example “I studied the .Notice several things about this sentence درس ُت الكتا ب book” is rendered in Arabic as is not used in the sentence. Such pronouns are usually not أنا ”,First, the pronoun for “I used, since the verb conjugation tells us who the subject is. These pronouns are used sometimes for emphasis. Second, notice that I left most of the verb unvowelled. The only vowel I used is the vowel that tells you for which person the verb is being conjugated. Sometimes you may see such a vowel included in an authentic Arab text if there is a chance of ambiguity. However, usually the verb, like all words, will be completely unvocalized. Notice that the verb ends in a vowel and that the vowel will elide the hamza on the definite article. ends in a fatha. The fatha is the accusative case الكتا ب ,Fourth, the direct object of the verb marker. I studied a document.” Notice that two fathas are used“ درس ُت وثيقة :Look at this sentence here. The second fatha gives us the nunation. This is just like the other two cases, nominative and genitive where the second dhanuna and second kasra provide the nunation. So, we use one fatha if the word is definite and two fathas if the word is indefinite. But there درست كتابا :is just a little bit more. Look at the following This is “I studied a book.” Here the indefinite direct object ends in two fathas but we have also added an alif. -

Introduction to Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles: ALAOTSIKKO

1 Introduction to Case, animacy and semantic roles Please cite this paper as: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi and Jussi Ylikoski. (2011) Introduction to case, animacy and semantic roles. In: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi & Jussi Ylikoski (Eds.), Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles, 1-26. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Seppo Kittilä Katja Västi Jussi Ylikoski University of Helsinki University of Oulu University of Helsinki University of Helsinki 1. Introduction Case, animacy and semantic roles and different combinations thereof have been the topic of numerous studies in linguistics (see e.g. Næss 2003; Kittilä 2008; de Hoop & de Swart 2008 among numerous others). The current volume adds to this list. The focus of the chapters in this volume lies on the effects that animacy has on the use and interpretation of cases and semantic roles. Each of the three concepts discussed in this volume can also be seen as somewhat problematic and not always easy to define. First, as noted by Butt (2006: 1), we still have not reached a full consensus on what case is and how it differs, for example, from 2 the closely related concept of adpositions. Second, animacy, as the label is used in linguistics, does not fully correspond to a layperson’s concept of animacy, which is probably rather biology-based (see e.g. Yamamoto 1999 for a discussion of the concept of animacy). The label can therefore, if desired, be seen as a misnomer. Lastly, semantic roles can be considered one of the most notorious labels in linguistics, as has been recently discussed by Newmeyer (2010). There is still no full consensus on how the concept of semantic roles is best defined and what would be the correct or necessary number of semantic roles necessary for a full description of languages. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

Prior Linguistic Knowledge Matters : the Use of the Partitive Case In

B 111 OULU 2013 B 111 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O.B. 7500 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA SERIES EDITORS HUMANIORAB Marianne Spoelman ASCIENTIAE RERUM NATURALIUM Marianne Spoelman Senior Assistant Jorma Arhippainen PRIOR LINGUISTIC BHUMANIORA KNOWLEDGE MATTERS University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen CTECHNICA THE USE OF THE PARTITIVE CASE IN FINNISH Docent Hannu Heusala LEARNER LANGUAGE DMEDICA Professor Olli Vuolteenaho ESCIENTIAE RERUM SOCIALIUM University Lecturer Hannu Heikkinen FSCRIPTA ACADEMICA Director Sinikka Eskelinen GOECONOMICA Professor Jari Juga EDITOR IN CHIEF Professor Olli Vuolteenaho PUBLICATIONS EDITOR Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FINNISH LANGUAGE ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Print) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS B Humaniora 111 MARIANNE SPOELMAN PRIOR LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE MATTERS The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Human Sciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in Keckmaninsali (Auditorium HU106), Linnanmaa, on 24 May 2013, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2013 Copyright © 2013 Acta Univ. Oul. B 111, 2013 Supervised by Docent Jarmo H. Jantunen Professor Helena Sulkala Reviewed by Professor Tuomas Huumo Associate Professor Scott Jarvis Opponent Associate Professor Scott Jarvis ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Printed) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2013 Spoelman, Marianne, Prior linguistic knowledge matters: The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Humanities, Finnish Language, P.O. -

Objective and Subjective Genitives

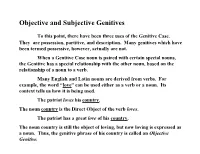

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Nominative and Objective Cases Reteaching

Name Date Lesson 1 Nominative and Objective Cases Reteaching Personal pronouns change form depending on how they function in a sentence. The form of a pronoun is called its case. The cases are nominative, objective, and possessive. Nominative Objective Possessive Singular First Person I me my, mine Second Person you you your, yours Third Person he, she, it him, her, it his, her, hers, its Plural First Person we us our, ours Second Person you you your, yours Third Person they them their, theirs The nominative form of a personal pronoun is used when the pronoun functions as a subject, as part of a compound subject, or as a predicate nominative. A pronoun used as a predicate nominative is called a predicate pronoun. It takes the nominative case. SUBJECT She is my mother’s niece. PART OF COMPOUND SUBJECT She and I are cousins. PREDICATE PRONOUN The cousin I most resemble is she. The objective form of a personal pronoun is used when the pronoun functions as a direct object, indirect object, or object of a preposition. Use it also when the pronoun is part of a compound object, or when it’s used with an infinitive. An infinitive is the base form of a verb preceded by the word to —to visit, to jog, to play. DIRECT OBJECT You can see her in these old family portraits. INDIRECT OBJECT My aunt sent me invitations to her wedding. OBJECT OF PREPOSITION A distant cousin has been searching for us. PART OF COMPOUND OBJECT My aunt reserved rooms for them and us. -

Finnish Partitive Case As a Determiner Suffix

Finnish partitive case as a determiner suffix Problem: Finnish partitive case shows up on subject and object nouns, alternating with nominative and accusative respectively, where the interpretation involves indefiniteness or negation (Karlsson 1999). On these grounds some researchers have proposed that partitive is a structural case in Finnish (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001). A problematic consequence of this is that Finnish is assumed to have a structural case not found in other languages, losing the universal inventory of structural cases. I will propose an alternative, namely that partitive be analysed instead as a member of the Finnish determiner class. Data: There are three contexts in which the Finnish subject is in the partitive (alternating with the nominative in complementary contexts): (i) indefinite divisible non-count nouns (1), (ii) indefinite plural count nouns (2), (iii) where the existence of the argument is completely negated (3). The data are drawn from Karlsson (1999:82-5). (1) Divisible non-count nouns a. Partitive mass noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative mass noun = def Purki-ssa on leipä-ä. Leipä on purki-ssa. tin-INESS is bread-PART Bread is tin-INESS ‘There is some bread in the tin.’ ‘The bread is in the tin.’ (2) Plural count nouns a. Partitive count noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative count noun = def Kadu-lla on auto-j-a. Auto-t ovat kadulla. Street-ADESS is.3SG car-PL-PART Car-PL are.3PL street-ADESS ‘There are cars in the street.’ ‘The cars are in the street.’ (3) Negation a. Partitive, negation of existence b. c.f.