Local Politics and Administrative Capacity for Disaster Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutritional Status and Social Influences in Dalit and Brahmin Women and Children in Lamjung Using Mixed Methods

Nutritional status and social influences in Dalit and Brahmin women and children in Lamjung using mixed methods A. Objective and Specific Aims Objective: - To measure nutritional status, of women (18-44 years) and children under five (6-59 months), of Dalit and Brahmins by taking anthropometric measures in Lamjung district, Western Nepal - To conduct structured surveys and qualitative assessments of how underlying social and behavioral factors, e.g. availability, access and utilization of food, and childcare, influence nutritional status of Dalit and Brahmin women and their children Specific Aims: - To obtain the anthropometric measurements of height, weight and upper arm circumference to determine indicators of nutritional status including underweight, stunting and wasting among children under five; and to determine body mass index (BMI) among their mothers and stepmothers (if living in a same household) - To administer structured surveys to obtain household and socio-demographic information such as number of offspring and co-wives, caste status (Dalits or Brahmins), age of women and children, socio-economic status (SES) and food insecurity information - To conduct in-depth interviews of a subsample of Dalit and Brahmin women to understand how socio-cultural aspects in their lives affect food insecurity B. Background and significance It can be hypothesized that in Nepal, the social status of Dalit women– a collection of the untouchable castes – could contribute to having a lower nutritional status of themselves and their children, compared to maternal and child malnutrition among Brahmin castes (the highest ranked caste) residing in the same villages. This association between social status and malnutrition has been consistently found in developing nations (Gurung, 2010). -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

ESMF – Appendix

Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) - Appendix 30 March 2020 Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Appendix Appendix 1: ESMS Screening Report - Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Appendix 2: Rapid social baseline analysis – sample template outline Appendix 3: ESMS Screening questionnaire – template for screening of sub-projects Appendix 4: Procedures for accidental discovery of cultural resources (Chance find) Appendix 5: Stakeholder Consultation and Engagement Plan Appendix 6: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 7: Social Impact Assessment (SIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 8: Developing and Monitoring an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) - Guidance Note Appendix 9: Pest Management Planning and Outline Pest Management Plan - Guidance Note Appendix 10: References Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) 2 Appendix 1 ESMS Questionnaire & Screening Report – completed for GCF Funding Proposal Project Data The fields below are completed by the project proponent Project Title: Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Project proponent: IUCN Executing agency: IUCN in partnership with the Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management (Nepal) and -

Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung

Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung: A Case of Hariyo Ban Project Dil B. Khatri Tikeshwari Joshi Bikash Adhikari Adam Pain CCRI case study 3 Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung: A Case of Hariyo Ban Project Dil B. Khatri, ForestAction Nepal Tikeshwari Joshi, Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Bikash Adhikari, ForestAction Nepal Adam Pain, Danish Institute for International Studies Climate Change and Rural Institutions Research Project In collaboration with: Copyright © 2015 ForestAction Nepal Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Published by ForestAction Nepal PO Box 12207, Kathmandu, Nepal Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Baneshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal Photos: Bikash Adhikari Design and Layout: Sanjeeb Bir Bajracharya Suggested Citation: Khatri, D.B., Joshi, T., Adhikari, B. and Pain, A. 2015. Climate change project implementation in Lamjung: A case of Hariyo Ban Project. Case Study Report 3. Kathmandu: ForestAction Nepal and Southasia Institute of Advance Studies. The views expressed in this discussion paper are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of ForestAction Nepal and SIAS. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Socio-economic and disaster context of Lamjung district ....................................................... 2 3. Hariyo Ban project: problem framing and project design ...................................................... -

Vol 2014-01 Enlift Project Site Selection Report

Volume 2014-01 ISSN 2208-0392 RESEARCH PAPER SERIES on Agroforestry and Community Forestry in Nepal The Research Paper Series on Agroforestry and Community Forestry in Nepal is published bi-monthly by “Enhancing livelihoods and food security from agroforestry and community forestry in Nepal”, or the EnLiFT Project (http://enliftnepal.org/). EnLiFT Project is funded by the Australian Centre of International Agricultural Research (ACIAR Project FST/2011/076). EnLiFT was established in 2013 and is a collaboration between: University of Adelaide, University of New South Wales, World Agroforestry Centre, Department of Forests (Government of Nepal), International Union for Conservation of Nature, ForestAction Nepal, Nepal Agroforestry Foundation, SEARCH-Nepal, Institute of Forestry, and Federation of Community Forest Users of Nepal. This is a peer-reviewed publication. The publication is based on the research project funded by Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). Manuscripts are reviewed typically by two or three reviewers. Manuscripts are sometimes subject to an additional review process from a national advisory group of the project. The editors make a decision based on the reviewers' advice, which often involves the invitation to authors to revise the manuscript to address specific concern before final publication. For further information, contact EnLiFT: In Nepal In Australia In Australia ForestAction Nepal University of Adelaide The University of New South Wales Dr Naya Sharma Paudel Dr Ian Nuberg Dr Krishna K. Shrestha Phone: +997 985 101 5388 Phone: +61 421 144 671 Phone: +61 2 9385 1413 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2208-0392 Disclaimer and Copyright The EnLiFT Project (ACIAR FST/2011/076) holds the copyright to its publications but encourages duplication, without alteration, of these materials for non-commercial purposes. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

Strengthening the Role of Civil Society and Women in Democracy And

HARIYO BAN PROGRAM Monitoring and Evaluation Plan 25 November 2011 – 25 August 2016 (Cooperative Agreement No: AID-367-A-11-00003) Submitted to: UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NEPAL MISSION Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by: WWF in partnership with CARE, FECOFUN and NTNC P.O. Box 7660, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal First approved on April 18, 2013 Updated and approved on January 5, 2015 Updated and approved on July 31, 2015 Updated and approved on August 31, 2015 Updated and approved on January 19, 2016 January 19, 2016 Ms. Judy Oglethorpe Chief of Party, Hariyo Ban Program WWF Nepal Baluwatar, Kathmandu Subject: Approval for revised M&E Plan for the Hariyo Ban Program Reference: Cooperative Agreement # 367-A-11-00003 Dear Judy, This letter is in response to the updated Monitoring and Evaluation Plan (M&E Plan) for the Hariyo Program that you submitted to me on January 14, 2016. I would like to thank WWF and all consortium partners (CARE, NTNC, and FECOFUN) for submitting the updated M&E Plan. The revised M&E Plan is consistent with the approved Annual Work Plan and the Program Description of the Cooperative Agreement (CA). This updated M&E has added/revised/updated targets to systematically align additional earthquake recovery funding added into the award through 8th modification of Hariyo Ban award to WWF to address very unexpected and burning issues, primarily in four Hariyo Ban program districts (Gorkha, Dhading, Rasuwa and Nuwakot) and partly in other districts, due to recent earthquake and associated climatic/environmental challenges. This updated M&E Plan, including its added/revised/updated indicators and targets, will have very good programmatic meaning for the program’s overall performance monitoring process in the future. -

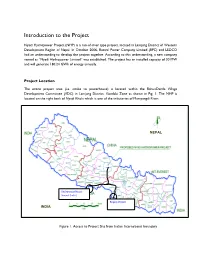

Introduction to the Project

Introduction to the Project Nyadi Hydropower Project (NHP) is a run-of-river type project, located in Lamjung District of Western Development Region of Nepal. In October 2006, Butwal Power Company Limited (BPC) and LEDCO had an understanding to develop the project together. According to this understanding, a new company named as “Nyadi Hydropower Limited” was established. The project has an installed capacity of 30 MW and will generate 180.24 GWh of energy annually. Project Location The entire project area (i.e. intake to powerhouse) is located within the BahunDanda Village Development Committee (VDC) in Lamjung District, Gandaki Zone as shown in Fig. 1. The NHP is located on the right bank of Nyadi Khola which is one of the tributaries of Marsyangdi River. NEPAL Bhairahawa (Nepal) Sunauli (India) Birganj (Nepal) INDIA Raxaul (India) Figure 1. Access to Project Site from Indian International boundary Fig. 2. Project location in Lamjung Access to Project site: The nearest road head to project site from district headquarter of Lamjung; Besisahar is located at Thakenbesi 22 km gravel road of Besisahar-Chame road. Road upto district headquarter Besisahar is blacktop. Besisahar is 185 km west from the Kathmandu and reach by the prithivi highway up to Dumre and Besisahar is 45 km from Dumre. Nearest Road head from Project Site be reached in following ways from the different parts of the Country. Technical Features of the Project Nyadi Hydropower Project is a run-of-the-river type project. The proposed system of the power plant will be run for its full capacity of 30 MW for about 5 months of the year. -

List of Persons Received Mason Training

Poverty Alleviation Fund Poverty Alleviation Fund Earthquake Response Program Seven Days Mason Training List of Participants District: Lamjhung Sn Participant Name Address Citizen No Age Gender Contact No. 1 Deu Bahadur Gurung Taghring-1 8265 54 Male 06.09.72.006 2 Ram Kumar Rai Taghring-1 70 28 Male 3 Yo Jung Gurung Taghring-3 65 48 Male 4 Meher Man Sarki Taghring-4 6341 54 Male 5 Ramesh Thapa Taghring-5 451004 28 Male 6 Bir Bahadur Gurung Taghring-6 108394 56 Male 7 Til Bahadur Gurung Taghring-7 3000(28) 30 Male 8 Kum Ras Gurung Taghring-8 269 48 Male 9 Sher Bahadur Gurung Taghring-8 19 Male Padam Bahadur Gotame (Pade 10 Sarki) Khudi-1 2515 50 Male 11 Bikram Bhandari Khudi-1 30268 40 Male 12 Janak Bahadur Bhandari Khudi-1 2618 41 Male 13 Krishna Bahadur Bhandari Khudi-1 55 Male 14 Singa Bahadur Gurung Khudi-2 7760 51 Male 15 Ash Bahadur Gurung Khudi-2 2771 56 Male 16 Padam Bahadur Tamang Khudi-4 26559 38 Male 17 Pash Bahadur Tamang Khudi-5 2828 51 Male 18 Ganesh B.K. Khudi-6 453005\113 39 Male Ghanpokhara- 45.01.72.034 19 Budh Prashad B.K. 1 04 19 Male Ghanpokhara- 20 Dudh Raj Kami 1 46837 32 Male Ghanpokhara- 21 Buddhi Bahadur B.K. 5 55680 27 Male Poverty Alleviation Fund Ghanpokhara- 22 Pode Kami 6 22902 43 Male Ghanpokhara- 23 Kalsai Gurung 7 14522 48 Male Ghanpokhara- 451007\1943 24 Yam Bahadur Gurung 8 4 26 Male Kholaswother- 25 Junga Bahadur Gurung 3 7074 60 Male Kholaswother- 26 Kum Bahadur Gurung 3 45227 30 Male Kholaswother- 27 Dhan Subba Gurung 3 2031 22 Male Kholaswother- 28 Ho Bahadur Gurung 3 40268 35 Male 29 Ganga Lal -

Gandaki Province

2020 PROVINCIAL PROFILES GANDAKI PROVINCE Surveillance, Point of Entry Risk Communication and and Rapid Response Community Engagement Operations Support Laboratory Capacity and Logistics Infection Prevention and Control & Partner Clinical Management Coordination Government of Nepal Ministry of Health and Population Contents Surveillance, Point of Entry 3 and Rapid Response Laboratory Capacity 11 Infection Prevention and 19 Control & Clinical Management Risk Communication and Community Engagement 25 Operations Support 29 and Logistics Partner Coordination 35 PROVINCIAL PROFILES: BAGMATI PROVINCE 3 1 SURVEILLANCE, POINT OF ENTRY AND RAPID RESPONSE 4 PROVINCIAL PROFILES: GANDAKI PROVINCE SURVEILLANCE, POINT OF ENTRY AND RAPID RESPONSE COVID-19: How things stand in Nepal’s provinces and the epidemiological significance 1 of the coronavirus disease 1.1 BACKGROUND incidence/prevalence of the cases, both as aggregate reported numbers The provincial epidemiological profile and population denominations. In is meant to provide a snapshot of the addition, some insights over evolving COVID-19 situation in Nepal. The major patterns—such as changes in age at parameters in this profile narrative are risk and proportion of females in total depicted in accompanying graphics, cases—were also captured, as were which consist of panels of posters the trends of Test Positivity Rates and that highlight the case burden, trend, distribution of symptom production, as geographic distribution and person- well as cases with comorbidity. related risk factors. 1.4 MAJOR Information 1.2 METHODOLOGY OBSERVATIONS AND was The major data sets for the COVID-19 TRENDS supplemented situation updates have been Nepal had very few cases of by active CICT obtained from laboratories that laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 till teams and conduct PCR tests. -

SASEC) Power System Expansion Project (SPEP

Environmental Impact Assessment February 2014 NEP: South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) Power System Expansion Project (SPEP) Prepared by Nepal Electricity Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Asian Development Bank Nepal: South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) Power System Expansion Project (SPEP) On-grid Components ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Draft – February 2014 i ADB TA 8272-NEP working draft – February 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Policy, Legal, and Administrative Framework 4 3 Description of the Project 19 4 Description of the Environment 28 Anticipated Environmental Impacts and Mitigation 5 96 Measures Information Disclosure, Consultation, and 6 112 Participation 7 Environmental Management Program 115 8 Conclusions and Recommendations 12 8 Appendices 1 Important Flora and Fauna 13 7 2 Habitat Maps 15 9 3 Summary of Offsetting Activities 16 9 Routing Maps in Annapurna Conservation Area