Nutritional Status and Social Influences in Dalit and Brahmin Women and Children in Lamjung Using Mixed Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESMF – Appendix

Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) - Appendix 30 March 2020 Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Appendix Appendix 1: ESMS Screening Report - Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Appendix 2: Rapid social baseline analysis – sample template outline Appendix 3: ESMS Screening questionnaire – template for screening of sub-projects Appendix 4: Procedures for accidental discovery of cultural resources (Chance find) Appendix 5: Stakeholder Consultation and Engagement Plan Appendix 6: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 7: Social Impact Assessment (SIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 8: Developing and Monitoring an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) - Guidance Note Appendix 9: Pest Management Planning and Outline Pest Management Plan - Guidance Note Appendix 10: References Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) 2 Appendix 1 ESMS Questionnaire & Screening Report – completed for GCF Funding Proposal Project Data The fields below are completed by the project proponent Project Title: Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Project proponent: IUCN Executing agency: IUCN in partnership with the Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management (Nepal) and -

Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung

Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung: A Case of Hariyo Ban Project Dil B. Khatri Tikeshwari Joshi Bikash Adhikari Adam Pain CCRI case study 3 Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung: A Case of Hariyo Ban Project Dil B. Khatri, ForestAction Nepal Tikeshwari Joshi, Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Bikash Adhikari, ForestAction Nepal Adam Pain, Danish Institute for International Studies Climate Change and Rural Institutions Research Project In collaboration with: Copyright © 2015 ForestAction Nepal Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Published by ForestAction Nepal PO Box 12207, Kathmandu, Nepal Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Baneshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal Photos: Bikash Adhikari Design and Layout: Sanjeeb Bir Bajracharya Suggested Citation: Khatri, D.B., Joshi, T., Adhikari, B. and Pain, A. 2015. Climate change project implementation in Lamjung: A case of Hariyo Ban Project. Case Study Report 3. Kathmandu: ForestAction Nepal and Southasia Institute of Advance Studies. The views expressed in this discussion paper are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of ForestAction Nepal and SIAS. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Socio-economic and disaster context of Lamjung district ....................................................... 2 3. Hariyo Ban project: problem framing and project design ...................................................... -

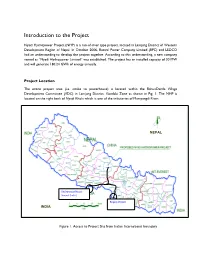

Introduction to the Project

Introduction to the Project Nyadi Hydropower Project (NHP) is a run-of-river type project, located in Lamjung District of Western Development Region of Nepal. In October 2006, Butwal Power Company Limited (BPC) and LEDCO had an understanding to develop the project together. According to this understanding, a new company named as “Nyadi Hydropower Limited” was established. The project has an installed capacity of 30 MW and will generate 180.24 GWh of energy annually. Project Location The entire project area (i.e. intake to powerhouse) is located within the BahunDanda Village Development Committee (VDC) in Lamjung District, Gandaki Zone as shown in Fig. 1. The NHP is located on the right bank of Nyadi Khola which is one of the tributaries of Marsyangdi River. NEPAL Bhairahawa (Nepal) Sunauli (India) Birganj (Nepal) INDIA Raxaul (India) Figure 1. Access to Project Site from Indian International boundary Fig. 2. Project location in Lamjung Access to Project site: The nearest road head to project site from district headquarter of Lamjung; Besisahar is located at Thakenbesi 22 km gravel road of Besisahar-Chame road. Road upto district headquarter Besisahar is blacktop. Besisahar is 185 km west from the Kathmandu and reach by the prithivi highway up to Dumre and Besisahar is 45 km from Dumre. Nearest Road head from Project Site be reached in following ways from the different parts of the Country. Technical Features of the Project Nyadi Hydropower Project is a run-of-the-river type project. The proposed system of the power plant will be run for its full capacity of 30 MW for about 5 months of the year. -

SOCOD NEPAL Profile

Organizational Profile ;dfh pTyfg ;fd'bflos ;:yf g]kfn 1.Name of Organization: SOCIETY FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT NEPAL (SOCOD-NEPAL) Main Office: Address: Besishahar 1 Jhingakhola, Lamjung Email: [email protected] Contact person for quaries Name: Pashupati Nath Neupane Position Chairman, E-mail: [email protected] Mobile: 9846437635 2. Registration Regd. No123/053/2053-07 District Administration Office, Lamjung, Nepal. Affiliation: No: 5874/054/02/02 Social Welfare Council, Kathmandu, Nepal. NGO Federation, Lamjung Chapter. District Development Committee NGO Coordination Committee, Lamjung Disaster Preparedness Network (DPNET) Nepal 2064 Last General Assembly Date: 2068/12/13 Last Election date: 2068/12/13 Last Audit Report Date: 2068/06/25 Last Renewal Date: 2068/06/30(for three years) Permanent Account Number: 302345265 3. Organizational Background SOCOD is a non profit making community development organization. It was established as an NGO to work towards social development activities in 1996. The headquarters of SOCOD is located in Besisahar Lamjung. It is registered as a non government organization (NGO) under the Society registration Act 1997 in district Administration Office Lamjung (.Regd N0--123/053/2053-07.) It is affiliated with Social Welfare Council, (Affiliation: No:--5874/054/02/02 ) Nepal And also member of DPNet Nepal. SOCOD is dedicated to the empowerment of poor rural people and to ensure their participation in the development process. It is actively working in various fields of community development mainly raising awareness among the rural poor people on the field of Health Environment, Education Art and Culture. It is also paying attention to well being of children. -

Kwhlosothar Rural Municipality

Kwhlosothar Rural Municipality Madhya Nepal Municipality. Rural municipalities. Dordi Rural Municipality. Dudhpokhari Rural Municipality. Kwhlosothar Rural Municipality. Marsyandi Rural Municipality. Former VDCs. Archalbot. Rural Municipality on WN Network delivers the latest Videos and Editable pages for News & Events, including Entertainment, Music, Sports, Science and more, Sign up and share your playlists. History. The Municipal Ordinance of 1883 was enacted by the North-West Territories to provide services to a rural area and provide some means of municipal governing. Saskatchewan and Alberta became provinces in 1905. Kwhlosothar Rural Municipality is one of the local level of Lamjung District out of 8 local levels. It has 9 wards and according to [2011 Nepal census]], 10,032 people live there. It has 175.37 square kilometres (67.71 sq mi) area. Its center is in the office of previous Maling V.D.C. Besisahar Municipality; Marsyandi Rural Municipality are in the east, Kaski District is in the west, Kaski District and Marsyandi Rural Municipality are in the north and Madhya Nepal Municipality and Besisahar Sundarbazar Municipality is in the east, Kaski district is in the west, Kwhlosothar Rural Municipality and Besisahar Municipality are in the north and Tanahun District is in the south of Madhya Nepal Municipality. Previous Madhya Nepal Municipality (all wards), previous Karaputar Municipality (all wards) and previous Neta V.D.C. (all wards) are included in this newly made municipality. References[edit]. v. Nepal, however, will not be alone in having rural municipalities, since Canada uses the term â˜rural municipalityâ™ in Manitoba and Saskatchewan provinces. A version of this article appears in print on March 15, 2017 of The Himalayan Times. -

Hariyo Ban Program

HARIYO BAN PROGRAM Semiannual Performance Report July 2019 – December 2019 (Cooperative Agreement No: AID-367-A-16-00008) Submitted to: THE UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NEPAL MISSION Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by: WWF in partnership with CARE, FECOFUN and NTNC P.O. Box 7660, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted on: 01 February 2020 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................viii 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Goal and Objectives ........................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Overview of Beneficiaries and Stakeholders ..................................................................... 1 1.3. Working Areas ................................................................................................................... 2 2. SEMI-ANNUAL PERFORMANCE .......................................................................................... 4 2.1. Biodiversity Conservation .................................................................................................. 4 2.2. Climate Change Adaptation ............................................................................................. 20 2.3. Gender Equality and Social Inclusion ............................................................................. 29 2.4. Governance -

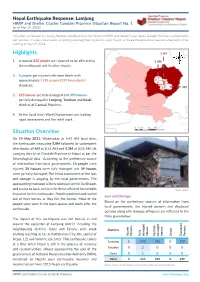

Lamjung HRRP and Shelter Cluster Gandaki Province Situation Report No

Gandaki Province Nepal Earthquake Response: Lamjung HRRP and Shelter Cluster Gandaki Province Situation Report No. 1 (as of May 19, 2021) This report is produced by Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform (HRRP) and Shelter Cluster Nepal, Gandaki Province in collaboration with partners. It covers the situation of Lamjung and neighbouring districts after the jolt of the earthquake and subsequent aftershocks in the morning of May 19, 2021. Highlights 5.8M 1. A total of 635 people are reported to be affected by 5.3M the earthquake and its after-shocks. 2. 5 people got injured with none death with approximately 1195 people (239 households) displaced. 4M 3. 245 houses are fully damaged and 395 houses partially damaged in Lamjung, Tanahun and Kaski districts of Gandaki Province. 4. At the Local level, Ward Chairpersons are leading rapid assessment and the relief work. Situation Overview On 19 May 2021, Wednesday at 5:42 AM local time, the earthquake measuring 5.8M followed by subsequent aftershocks of 4M at 8:16 AM and 5.3M at 8:26 AM, hit Lamjung district of Gandaki Province in Nepal as per the Seismological data. According to the preliminary source of information from local governments, 15 people were injured; 35 houses were fully damaged and 49 houses were partially damaged. The initial assessment of the loss and damage is ongoing by the local governments. The approaching monsoon is likely to impact on the livelihoods and access to basic services for these affected households Photo: HRRP impacted by this earthquake. People panicked and rushed Loss and Damage out of their homes as they felt the tremor. -

A Case Study of Karaputar Municipality, Lamjung a Thesis

SITUATION OF DOMESTIC CHILD LABOURER: A Case Study of Karaputar Municipality, Lamjung A Thesis Submitted to The Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University, In partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of the Master of Arts (M.A) in Rural Development By KOPILA BHUSAL Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu T.U. Reg No. : 9-2-375-46-2005 Roll No. : 282118 July, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled "Situation of Domestic Child Labourer: A Case Study of Karaputar Municipality, Lamjung” Submitted to the Central Department of Rural Development, Tribhuvan University, is entirely my original work prepared under the guidance and supervision of my supervisor. I have made due acknowledgements to all ideas and information borrowed from different sources in the course of preparing this thesis. The results of this thesis have not been presented or submitted anywhere else for the award of any degree or for any other purpose. I assure that no part of the content of this thesis has been published in any from before. Kopila Bhusal TU Reg. No: 9-2-375-46-2005 Date : 24/7/2016 09/04/2073 2 RECOMMENDATION LETTER This thesis entitled "SITUATION OF DOMESTIC CHILD LABOURER: A CASE STUDY OF KARAPUTAR MUNICIPALITY, LAMJUNG” has been prepared by Mrs. Kopila Bhusal under my guidance and supervision. I found her work Satisfactory. I would like to forward this dissertation for final approval. …………………….. Prajwal Man Pradhan Supervisor Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuwan University Kirtipur, Kathmandu Date : 24/7/2016 09/04/2073 3 APPROVAL LETTER This is to certify that this thesis entitled "Situation of Domestic Child Labourer: A case Study of Karaputar Municipality, Lamjung", submitted by Mrs. -

Municipal Profile of Rainas Municipality, Lamjung, Nepal

TRIBHUWAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING M.SC. URBAN PLANNING MUNICIPALITY PROFILE OF RAINAS, LAMJUNG Submitted by: M.Sc. Urban Planning/ 072 batch Submitted to: Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development (MoFALD) Acknowledgement We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Mr. Chakrapani Sharma, Deputy Secretary, Mr.Purna Chandra Bhattarai, Joint Secretary and Mr. Chranjibi Timalsina of Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development (MoFALD) for financial support, Rainas Municipality, Nepal Engineers’ Association (NEA) and University of New South Wales (UNSW), Australia for their encouragement. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our course coordinator of Planning Studio - I, Prof. Dr. Sudha Shrestha and also our tutor Ar. Nisha Shrestha for their generosity and encouragement in completing this studio work. Their valuable guidance, suggestions and enthusiastic support to complete this municipal profile is highly appreciable. We highly appreciate timely guidance provided by Mr. Sanjaya Uperty, Mr. Nagendra Bahadur Amatya and Mr. Ashim Ratna Bajracharya of IOE, Pulchowk for their valuable guidance and suggestions to prepare this municipality profile. Also special thanks to Mr. Prem Chaudary for his help throughout the field visit. The study team is highly obliged to Er. Dinesh Panthy and Mr. Dharmendra Gurung for their valuable help and support. We would also like to thank Mr. Nur Raj Kadariya, Executive Officer, of Rainas Municipality. Our special thanks to social mobilizers Mr. Bikash Gurung, Ms. Kala Lamichane and Ms Pabitra Chiluwal. We are also grateful to all the residents of Rainas Municipality for helping us by providing necessary information in preparing this municipality profile. -

CHITWAN-ANNAPURNA LANDSCAPE: a RAPID ASSESSMENT Published in August 2013 by WWF Nepal

Hariyo Ban Program CHITWAN-ANNAPURNA LANDSCAPE: A RAPID ASSESSMENT Published in August 2013 by WWF Nepal Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. Citation: WWF Nepal 2013. Chitwan Annapurna Landscape (CHAL): A Rapid Assessment, Nepal, August 2013 Cover photo: © Neyret & Benastar / WWF-Canon Gerald S. Cubitt / WWF-Canon Simon de TREY-WHITE / WWF-UK James W. Thorsell / WWF-Canon Michel Gunther / WWF-Canon WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program / Pallavi Dhakal Disclaimer This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Kathmandu Forestry College (KAFCOL) and do not necessarily reflect the views of WWF, USAID or the United States Government. © WWF Nepal. All rights reserved. WWF Nepal, PO Box: 7660 Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal T: +977 1 4434820, F: +977 1 4438458 [email protected] www.wwfnepal.org/hariyobanprogram Hariyo Ban Program CHITWAN-ANNAPURNA LANDSCAPE: A RAPID ASSESSMENT Foreword With its diverse topographical, geographical and climatic variation, Nepal is rich in biodiversity and ecosystem services. It boasts a large diversity of flora and fauna at genetic, species and ecosystem levels. Nepal has several critical sites and wetlands including the fragile Churia ecosystem. These critical sites and biodiversity are subjected to various anthropogenic and climatic threats. Several bilateral partners and donors are working in partnership with the Government of Nepal to conserve Nepal’s rich natural heritage. USAID funded Hariyo Ban Program, implemented by a consortium of four partners with WWF Nepal leading alongside CARE Nepal, FECOFUN and NTNC, is working towards reducing the adverse impacts of climate change, threats to biodiversity and improving livelihoods of the people in Nepal. -

FPIC Protocol

FREE, PRIOR, AND INFORMED BY COMMUNITIES AFFECTED BY THE CONSENT EIB FUNDED 220 KV MARSYANGDI PROTOCOL CORRIDOR IN NEPAL FPIC & RIGHTS FORUM OCTOBER 8, 2020 First published in 2020 by FPIC & Rights Forum Lamjung District, Nepal Lawyers’ Association for Human Rights of Nepalese Indigenous Peoples (LAHURNIP) Anamnagar, Kathmandu PO Box No.: 11179 Contact: +977 01 4268510 Email: [email protected] We would like to extend our gratitude to all the participants, Report design by Rose Flanigan both Indigenous Peoples and people belonging to other roseflanigan.com caste and ethnic groups, who attended preliminary community level consultation meetings organized at Taal First Edition: 2020 in Manang, and at Ghermu, Archalbot, and Dhamil Kuwa FPIC & Rights Forum in Lamjung from 25 to 27 April 2019, and community level Lamjung District, Nepal consultation meetings at Dharapani in Manang, and at Ghermu, Khudi, Khasur, Archalbot, Banjhakhet and Dhamil Copyright © Lawyers’ Association for Human Rights of Kuwa in Lamjung from 24 May 2019 to 2 June 2019. Also, Nepalese Indigenous Peoples (LAHURNIP) our thanks to Khemjung Gurung (Chairperson, FPIC & Rights Forum), Chandra Mishra (Secretary, FPIC & Rights Forum), This book may be reproduced in whole or in part in any Dudha Kashi Gurung (Chairperson, Nepal Federation of form for educational, training or nonprofit purposes with due Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN-Lamjung)), and Journalist acknowledgment of the source. No use of this publication Aas Bahadur Gurung, for actively participating in the may -

Who Benefits? Gender Equity and Social Inclusion Among Community Forest User Groups in Nepal: Who Benefits?

WHO BENEFITS? GENDER EQUITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION AMONG COMMUNITY FOREST USER GROUPS IN NEPAL: WHO BENEFITS? A Capstone Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Professional Studies in Agriculture and Life Sciences Field of Global Development by Leala Rosen August 2020 © 2020 Leala Rosen ABSTRACT Community forestry programs in Nepal have been incredibly successful in terms of carbon sequestration, reforestation, and localized environmental conservation practices. Nepal’s community forest initiatives are managed by national policies and a decentralized method of community-based natural resource management, community forest monitoring, and local leadership. The decentralized governance model of Nepal’s community forestry initiatives has been replicated in several other developing countries, and there are numerous environmental benefits. However, the role of gender equity and social inclusion among these groups is unclear. Although substantial efforts in terms of gender mainstreaming and social inclusion initiatives have been undertaken and women participate in and lead community forest user groups (CFUGs), barriers to group entry limit social inclusion. This paper analyzes the socioeconomic and environmental benefits of participation in community forest user groups in Nepal, with a critical lens of gender equity and social inclusion. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Leala Rosen is from Dallas, Texas, and holds a Bachelor’s of Arts in Sociology/Anthropology with a concentration in Environmental Studies from Hendrix College. Her deep love of nature, conservation, and sustainable food systems comes from her time as an undergraduate, where she fell in love with camping, hiking, traveling, and community gardening.