Report on the Extended Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volantino SAD Anziani.Pub

CHI SIAMO Fondazione Aquilone Onlus rappresenta Fondazione Aquilone ha maturato una l’ideale continuazione e sviluppo consolidata esperienza nella gestione di servizi dell’esperienza dell’associazione di V.S.P. per persone anziane in convenzione o www.fondazioneaquilone.org Bruzzano Onlus (Volontari Sostegno collaborazione con il Comune di Milano: Persona). In oltre 25 anni di attività, grazie Servizio Custodi Sociali nei quartieri di anche all’intensificarsi dei rapporti con le Bruzzano, Comasina, Bovisasca e Riguarda. istituzioni locali (Comune, Provincia, Estate amica - pronto intervento estivo, nei Regione, ASL, Scuole), è stato possibile dare quartieri di Affori, Bruzzano e Comasina. alcuni contributi significativi alla Interventi di assistenza domiciliare privata o SERVIZIO realizzazione di comunità locali attente alla tramite "buono sociale" del Comune qualità di vita di alcuni quartieri (Bruzzano, Comasina, Bovisasca, Città studi). La Tenda - un servizio di prossimità e socialità "per e con" gli anziani in Città Studi ASSISTENZA I punti di forza e di qualità dei servizi e dei progetti di Fondazione Aquilone, che hanno Inoltre gestisce servizi e progetti rivolti a saputo inserirsi nel contesto dei diversi Piani famiglie, bambini, adolescenti, giovani, disabili. DOMICILIARE di zona della Città, sono: prossimità e Ulteriori informazioni su Internet all’indirizzo solidarietà ben radicate in alcuni quartieri www.fondazioneaquilone.org della zona 9; prendersi cura di chi vive per persone anziane momenti di fragilità; passione di educare condivisa con le persone e le famiglie DOVE SIAMO percepite partner nei processi educativi e sociali e non semplice utenti di servizi; animazione di comunità e lavoro di rete con Servizio accreditato con le istituzioni e le diverse risorse del Fondazione Aquilone Onlus SERVIZIO ASSISTENZA DOMICILIARE territorio; flessibilità e personalizzazione degli interventi; sinergia tra operatori e piazza Bruzzano 8 Milano Il sistema dell’accreditamento, volontari . -

Comune.Milano.It/Municipio9

comune.milano.it/municipio9 DENOMINAZIONE INDIRIZZO (Via, NUMER Note Quartiere SERVIZIO SVOLTO Orari garantiti Telefono 1 Telefono 2 Mail SOCIALE P.zza) O CIVICO (Facoltativo) servizio in convenzione con diapason assistenza domiciliare anziani e 7-18 da lunedì a il comune di cooperativa sociale municipio 9 disabili sabato 3333992104 [email protected] milano diapason confezionamento e distribuzione 9-13 da lunedì a cooperativa sociale municipio 9 via santa monica 4 alimenti venerdi 3333992104 [email protected] raccolta bisogni dai cittadini allo servizio in 020202 e servizi di convenzione con diapason accompagnamento, consegna pasti 9-16 da lunedì a il comune di cooperativa sociale municipio 9 vpiazza bruzzano e medicinali venerdi 20202 milano Servizio Spesa e farmaci: dalle 9 alle 16 - supporto servizio svolto Spesa a domicilio, consegna ricette psicologico attivo operatrici WeMi Elisa con operatori con Cooperativa Cascina e farmaci con Milano Aiuto. nei giorni : martedì Mussari e Celeste responsabile richiesta Biblioteca/ WeMi Niguarda Affori Supporto psicologico telefonico con mecoledì venerdì Bressi T. servizio: Monica Villa [email protected]; contributo Ornato Dergano Via Luigi Ornato 7 psicologo dedicato. dalle 9 alle 16. 3401113392 T. 342.3302952 [email protected] nell'ordine di €5 via Casoria (sede dal lunedì al Cooperativa Cascina su tutto in legale servizio di assistenza domiciliare venerdì dalle 9 alle Sonia Zaffaroni T. Biblioteca Municipio 9 cooperativa) 50 Anziani. 17 340.6119986 [email protected] -

Ai Margini Dello Sviluppo Urbano. Uno Studio Su Quarto Oggiaro Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale

Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano. Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale To cite this version: Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale. Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano. Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro: On the Fringes of Urban Development. A Study on Quarto Oggiaro. Bruno Mondadori Editore, pp.192, 2009. hal-01495479 HAL Id: hal-01495479 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01495479 Submitted on 25 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 1 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 2 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 1 Ricerca 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 2 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 3 Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro a cura di Rossana Torri e Tommaso Vitale Bruno Mondadori 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 4 Il volume è finanziato da Acli Lombardia. Tutti i diritti riservati © 2009 Pearson Italia, Milano-Torino Prima pubblicazione: dicembre 2009 Per i passi antologici, per le citazioni, per le riproduzioni grafiche, cartografiche e fotografiche appartenenti alla proprietà di terzi, inseriti in quest’opera, l’editore è a disposizione degli aventi diritto non potuti reperire nonché per eventuali non volute omissioni e/o errori di attribuzione nei riferimenti. -

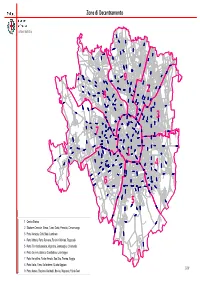

Impagin 9 Zone

Zone di Decentramento Settore Statistica V i a C o m a s i n a V ia V l i e a R u G b . ic o P n a e s t a i t s e T . F e l a i V ani V gn i odi a ta M . Lit L A . Via V ia O l r e n E a . t F o e r V m i a i A s t e s a a n z i n orett i Am o Via C. M e l a i V V V i i a V a i B a M G o . v . L i B s . e a a G s s r s c d a o e s a r n s B i a . F ia V i t s e T V . V F i a a v i ado a l e P l ia e V P a i e E l . V l e F g e r r i n m o i V ia R o M s am s b i r et ti Piazza dell'Ospedale Maggiore a a v z o n n a o lm M a P e l ia a i V V a v Via V o G i d all a a ara ni P te B ia a o nd i a V v . C i G s ia V a V ia s A c a p a e l p i e C n n a in i i V V ia G al V V lar i i at ia hini a e V mbrusc Piazza h V i Via La C c V a r i a C Bausan . -

Nuclei Di Identita' Locale (NIL)

Schede dei Nuclei di Identità Locale 3 Nuclei di Identita’ Locale (NIL) Guida alla lettura delle schede Le schede NIL rappresentano un vero e proprio atlante territoriale, strumento di verifica e consultazione per la programma- zione dei servizi, ma soprattutto di conoscenza dei quartieri che compongono le diverse realtà locali, evidenziando caratteri- stiche uniche e differenti per ogni nucleo. Tale fine è perseguito attraverso l’organizzazione dei contenuti e della loro rappre- sentazione grafica, ma soprattutto attraverso l’operatività, restituendo in un sistema informativo, in costante aggiornamento, una struttura dinamica: i dati sono raccolti in un’unica tabella che restituisce, mediante stringhe elaborate in linguaggio html, i contenuti delle schede relazionati agli altri documenti del Piano. Si configurano dunque come strumento aperto e flessibile, i cui contenuti sono facilmente relazionabili tra loro per rispondere, con eventuali ulteriori approfondimenti tematici, a diverse finalità di analisi per meglio orientare lo sviluppo locale. In particolare, le schede NIL, come strumento analitico-progettuale, restituiscono in modo sintetico le componenti socio- demografiche e territoriali. Composte da sei sezioni tematiche, esprimono i fenomeni territoriali rappresentativi della dinamicità locale presente. Le schede NIL raccolgono dati provenienti da fonti eterogenee anagrafiche e censuarie, relazionate mediante elaborazioni con i dati di tipo geografico territoriale. La sezione inziale rappresenta in modo sintetico la struttura della popolazione residente attraverso l’articolazione di indicatori descrittivi della realtà locale, allo stato di fatto e previsionale, ove possibile, al fine di prospettare l’evoluzione demografica attesa. I dati demografici sono, inoltre, confrontati con i tessuti urbani coinvolti al fine di evidenziarne l’impatto territoriale. -

Relazione a Un Portico Molto Sviluppato in Lunghezza O All'insieme Dei Portici Costituenti Un Quadriportico, Un Chiostro O Un'altra Struttura Porticata

Politecnico di Milano Scuola di Architettura Civile Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Architettura Anno Accademico 2014/2015 Quella città è un perpetuo peristilio Un progetto per la rinascita della Bovisa Tesi di laurea di: Yin Wu (803950) Zhonghuan Wang (813548) Relatore: Prof. Giancarlo Consonni INDICE 1. Introduzione: 1.1. Il porticato nello spazio urbano 1.2. Il porticato nell’architettura orientale(Qi lou) 1.3. «Quella città è un perpetuo peristilio» 2. Analisi ed interpretazione del contesto 2.1 Lo sviluppo della metropoli milanese 2.1.1 I prodromi della nascita della metropoli: industria rurale e demografia 2.1.2 L'industrializzazione metropolitana 2.2 La formazione di Bovisa: la morfologia urbana nell’evoluzione storica 2.3 La topografia sociale, le attività umane e le relazioni urbane 2.3.1 I quartiere di Bovisa: analisi delle possibilità relazionali. 2.3.2 Topografia sociale e criticità nella composizione della popolazione 2.3.3 Le questioni affrontate nel progetto 3.La soluzione progettuale 3.1 La matrice del progetto 3.2 Le attività umane e le relazioni 3.3 L’architettura dei luoghi 4.Bibliografia INDICE DELLE TAVOLE TAV.1 Bovisa nella metropoli milanese TAV.2 Bovisa urbs TAV.3 Bovisa civitas TAV.4 Lo spazio delle relazioni e le infrastrutture al servizio della mobilità TAV.5 Planivolumetrico (scala 1:2000) TAV.6 Schemi di progetto TAV.7 Piante dei piani terra (scala 1:1000) TAV.8 Piante dei piani tipo (scala 1:1000) TAV.9 L’organismo universitario 1 TAV.10 L’organismo universitario 2 TAV.11 L’organismo scolastico 1 TAV.12 L’organismo -

International Student Guide

INTERNATIONAL STUDENT GUIDE Milan Seats Academic Year 2011/2012 CONTENTS General information about IED p. 3 Useful contacts p. 3 Holidays p. 3 School breaks p. 3 General schedule – Academic Year 2010/2011 p. 3 How to reach us p. 4 Airports p. 4 Railways p. 6 Practical information for EU‐students p. 7 “Iscrizione anagrafica”: regsitration at “Comune di Milano” p. 7 “Iscrizione anagrafica”: registration in a Municipality other than the city of Milan p. 7 Practical information for foreign (Non‐Eu) students p. 9 Visa for study p. 9 Declaration of presence p. 10 Residence Permit for non‐EU citizens p. 11 First time application (Residence Permit) p. 11 Important information for students waiting for their Residence Permit p. 14 Renewal of the Residence Permit p. 15 List of Post offices in Milan p. 16 List of Police stations in Milan p. 17 Immigration Office in Milan p. 18 Living in Milan . p. 21 Living expenses p. 21 Tax code p. 21 Health care p. 22 Open a bank account p. 26 Accommodation p. 27 Tickets and passes for public transport p. 30 Italian for foreigners p. 33 Utilities p. 33 Telephones p. 33 Tipping p. 33 Discounts p. 34 Entertainment p. 34 Foreign Embassies and Consulates in Milan p. 36 Bookmarks p. 37 Emergency: numbers and addresses p. 38 Other useful numbers p. 39 International Week p. 39 15 things to do in Milan at least once in your life ! p. 39 IED Offices p. 40 Documents attached (at the end of the guide) Facsimile 1 “Mod. -

Milano Porta Garibaldi:Un Nuovo Progetto Per La Città

POLITECNICO DI MILANO Facoltà di Architettura Civile Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Architettura MILANO PORTA GARIBALDI: UN NUOVO PROGETTO PER LA CITTA’ Relatore: Prof. Rosaldo BONICALZI Tesi di Laurea di: Alessandro DAVERIO Matr. 736160 Giuseppe SBRINI Matr. 725264 Anno Accademico 2010 / 2011 Politecnico di Milano- Facoltà di Architettura Civile Milano Porta Garibaldi:un nuovo progetto per la città Indice della relazione - 1. Introduzione …………………………………………………………………………………….. pag. 6 1.1 Il ruolo dell’architetto …………………………………………………………………………. pag. 6 - 2. Milano e gli Scali Ferroviari …………………………………………………………………… pag. 10 2.1 Lo sviluppo della rete ferroviaria a Milano ………………………………………………… pag. 10 2.2 Gli scali ferroviari ……………………………………………………………………………. pag. 14 2.2.1 Scalo Lambrate ………………………………………………………………………….. pag. 14 2.2.2 Scalo Rogoredo …………………………………………………………………………. pag. 15 2.2.3 Scalo Porta Genova …………………………………………………………………….. pag. 17 2.2.4 Scalo Porta Romana ……………………………………………………………………. pag. 18 2.2.5 Scalo Greco- Pirelli ……………………………………………………………………... pag. 19 2.2.6 Scalo Sempione e Scalo Garibaldi ……………………………………………………. pag. 20 2.2.7 Scalo Farini ……………………………………………………………………………… pag. 22 - 3. Bovisa-Garibaldi-Farini ………………………………………………………………………. pag. 24 3.1 Origini delle aree: scalo Farini, Garibaldi-Repubblica, Bovisa …………………………. pag. 24 3.2 Lo scalo Farini ……………………………………………………………………………….. pag. 25 3.3 Lo scalo Bovisa ……………………………………………………………………………... pag. 25 3.4 Lo scalo Garibaldi …………………………………………………………………………… pag. 27 - 4. Il progetto Garibaldi ………………………………………………………………………….. -

Elenco Schede NIL Per I Municipi Elenco Schede

4 Piano dei Servizi Elenco schede NIL Elenco schede NIL per i municipi 01. Duomo 54. Muggiano Municipio 1 Municipio 5 Municipio 8 02. Brera 55. Baggio - Q.re degli Olmi - Q.re Valsesia 1. Duomo 5. P.ta Vigentina - P.ta Lodovica 59. Tre Torri 03. Giardini P.ta Venezia 56. Forze Armate 2. Brera 6. P.ta Ticinese - Conca del Naviglio 64. Trenno 04. Guastalla 57. San Siro 3. Giardini Porta Venezia 36. Scalo Romana 65. Q.re Gallaratese - Q.re San Leonardo 05. P.ta Vigentina - P.ta Lodovica 58. De Angeli-Monte Rosa 4. Guastalla 34. Chiaravalle - Lampugnano 06. P.ta Ticinese - Conca del Naviglio 59. Tre Torri 7. Magenta- S. Vittore 37. Morivione 66. QT8 07. Magenta- S.Vittore 60. Stadio - Ippodromi 8. Parco Sempione 38. Vigentino - Q.re Fatima 67. Portello 08. Parco Sempione 61. Quarto Cagnino (5. Vigentina) 39. Quintosole 68. Pagano 09. P.ta Garibaldi - P.ta Nuova 62. Quinto Romano (6. Ticinese) 40. Ronchetto delle Rane 69. Sarpi 10. Stazione Centrale - Ponte Seveso 63. Figino (68. Pagano) 41. Gratosoglio - Q.re Missaglia 70. Ghisolfa 11. Isola 64. Trenno (69. Sarpi) - Q.re Terrazze 71. Villapizzone - Cagnola - Boldinasco 12. Maciachini-Maggiolina 65. Q.re Gallaratese - Q.re San Leonardo - Lampugnano 42. Stadera - Chiesa Rossa - Q.re Torretta 72. Maggiore - Musocco - Certosa 13. Greco - Segnano 66. QT8 Municipio 2 - Conca Fallata 73. Cascina Merlata 14. Niguarda - Ca’ Granda - Prato Centenaro - Q.re Fulvio Testi 67. Portello 10. Stazione Centrale - Ponte Seveso 43. Tibaldi 74. Roserio 15. Bicocca 68. Pagano 16. Gorla - Precotto 85. -

Daniel Baldwin Hess · Tiit Tammaru Maarten Van Ham Editors Housing Estates in Europe Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges the Urban Book Series

The Urban Book Series Daniel Baldwin Hess · Tiit Tammaru Maarten van Ham Editors Housing Estates in Europe Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges The Urban Book Series Series Advisory Editors Fatemeh Farnaz Arefian, University College London, London, UK Michael Batty, University College London, London, UK Simin Davoudi, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK Geoffrey DeVerteuil, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK Karl Kropf, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK Marco Maretto, University of Parma, Parma, Italy Vítor Oliveira, Porto University, Porto, Portugal Christopher Silver, University of Florida, Gainesville, USA Giuseppe Strappa, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy Igor Vojnovic, Michigan State University, East Lansing, USA Jeremy Whitehand, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK Aims and Scope The Urban Book Series is a resource for urban studies and geography research worldwide. It provides a unique and innovative resource for the latest developments in the field, nurturing a comprehensive and encompassing publication venue for urban studies, urban geography, planning and regional development. The series publishes peer-reviewed volumes related to urbanization, sustainabil- ity, urban environments, sustainable urbanism, governance, globalization, urban and sustainable development, spatial and area studies, urban management, urban infrastructure, urban dynamics, green cities and urban landscapes. It also invites research which documents urbanization processes and urban dynamics on a national, regional and local level, welcoming -

Programma Web Rev10

PROGRAMMA 28 SETTEMBRE Elle Dècor FabFood the new spaces 5 Vie D’N’A – Design and Art for a and rituals Better World Via Romagnosi, 3 Distretto 5Vie Info su www.elledecor.com Area compresa tra Via Cesare Correnti, Piazza Mentana, Via Santa INTERNI Designer’s Week (Milano) Marta e Via San Maurillo Meeting Point c/o Istituto Marangoni Info su : www.5vie.it/ Via Cerva, 24 Gallerie d’Italia - Piazza Scala, 6 Info su: www.internimagazine.it/ Green Design District – Sustainable Design for Future Cranium Vanitas Digital Via Marconi – Passaggio pedonale Info su www.greendesigndistrict.eu Museo del 900 Info su viareggio.ilcarnevale.com/ Time and Style Edition La Penna e la Spada Via Santa Cecilia, 7 Via A. Bazzini, 15 Info su www.depadova.com Info su: associazioneculturalesator.it/ FuoriSalone Design Edition Le Vie del Compasso D’oro 2020 Varie location Luoghi diversi a Milano e dintorni in presenza e in streaming Info su www.adi-design.org Info su www.fuorisalone.it Installazione in Piazza XXV Aprile Il Design Aiuta a Guarire Inspire Design Via Ceresio, 7 Via Durini e adiacenze Info su www.adi-design.org Info su: www.milanodurinidesign.it Art&Design Casa Cappellini AC Space in Via Adige, 11 Via Santa Cecilia, 4 Info su: Info su www.cappellini.com www.andreacastrignano.it/blog/ ArteDesign by Decor Lab New Buildings Via Tortona, 31 Via Solferino, 36 Info su: www.decorlab.it Info su www.matrix4design.com The Cassina Perspective 2020 Design For Circular Solutions Via Durini, 16 Digital Info su: www.cassina.com Info su www.classecohub.org Materially -

"Affori Centre: a Style of Work, a Way of Life

Incaricati della commercializzazione Un’iniziativa di - An initiative of: Exclusive marketing agents Affori Centre. A style of work, Bnp Paribas Cushman & Wakefield Real Estate Advisory Italy S.p.A. a way of life. Via Carlo Bo, 11 - 20143 Milano Via Turati 16/18 - 20121 Milano t. +39 02 32 11 53 t. +39 02 63 799 1 www.afforicentre.it www.realestate.bnpparibas.it www.cushmanwakefield.com Graphic Design: Fabio Zoratti Copy: Luca Nicola Photos: Beppe Raso Affori Centre Via Cialdini 31 Milano Benvenuto / Welcome Un edificio innovativo An innovative building Oltre a un ambiente moderno, stimolante e con- As well as being a modern ambience, stimulating Ubicazione e collegamenti Location and connections fortevole, Affori Centre è concepito per assicurare and comfortable, Affori Centre is designed to gua- la migliore qualità della vita a chi lo abita. È il valore rantee the best quality of life to those who work aggiunto straordinario di 5-Star ServicesTM, il pro- there. It is the extraordinary added value of 5-Star gramma che prevede servizi totalmente persona- ServicesTM, the programme that foresees totally lizzabili a seconda delle specifiche richieste dell’a- customizable services, according to the specific zienda. Reception e assistenza, aree ricreative, requirements of the company. Reception and area ristorazione, parcheggio biciclette, consierge assistance, recreation areas, refreshment area, privato: sono solo alcuni esempi di servizi a “5 stel- bicycle parking, private consierge: these are just le” che consentono ai dipendenti di concentrarsi some examples of the “5 star” services that allow Comasina totalmente sulla propria attività, migliorandone employees to concentrate totally on their specific A8 A9 A4 Tangenziale Nord M sensibilmente la produttività.