In and out of Catchment Areas Between Avoidance and Multiculturalism: Exploring the Transition to Lower Secondary School in Milan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volantino SAD Anziani.Pub

CHI SIAMO Fondazione Aquilone Onlus rappresenta Fondazione Aquilone ha maturato una l’ideale continuazione e sviluppo consolidata esperienza nella gestione di servizi dell’esperienza dell’associazione di V.S.P. per persone anziane in convenzione o www.fondazioneaquilone.org Bruzzano Onlus (Volontari Sostegno collaborazione con il Comune di Milano: Persona). In oltre 25 anni di attività, grazie Servizio Custodi Sociali nei quartieri di anche all’intensificarsi dei rapporti con le Bruzzano, Comasina, Bovisasca e Riguarda. istituzioni locali (Comune, Provincia, Estate amica - pronto intervento estivo, nei Regione, ASL, Scuole), è stato possibile dare quartieri di Affori, Bruzzano e Comasina. alcuni contributi significativi alla Interventi di assistenza domiciliare privata o SERVIZIO realizzazione di comunità locali attente alla tramite "buono sociale" del Comune qualità di vita di alcuni quartieri (Bruzzano, Comasina, Bovisasca, Città studi). La Tenda - un servizio di prossimità e socialità "per e con" gli anziani in Città Studi ASSISTENZA I punti di forza e di qualità dei servizi e dei progetti di Fondazione Aquilone, che hanno Inoltre gestisce servizi e progetti rivolti a saputo inserirsi nel contesto dei diversi Piani famiglie, bambini, adolescenti, giovani, disabili. DOMICILIARE di zona della Città, sono: prossimità e Ulteriori informazioni su Internet all’indirizzo solidarietà ben radicate in alcuni quartieri www.fondazioneaquilone.org della zona 9; prendersi cura di chi vive per persone anziane momenti di fragilità; passione di educare condivisa con le persone e le famiglie DOVE SIAMO percepite partner nei processi educativi e sociali e non semplice utenti di servizi; animazione di comunità e lavoro di rete con Servizio accreditato con le istituzioni e le diverse risorse del Fondazione Aquilone Onlus SERVIZIO ASSISTENZA DOMICILIARE territorio; flessibilità e personalizzazione degli interventi; sinergia tra operatori e piazza Bruzzano 8 Milano Il sistema dell’accreditamento, volontari . -

HOTEL D'este**** Viale Bligny, 23 Milano

HOTEL D’ESTE**** Viale Bligny, 23 Milano http://www.hoteldestemilano.it Tel:+39 02 58321001 Fax: +39 0258321136 E-mail [email protected] Hotel D'Este is located in the heart of Milan and near all major attractions of the city. 79 Rooms totally remodeled in 2001, offers superior class service in very quite atmosphere, tastefully hotel ideal for the business traveller. All the guest rooms are comfortable and nicely equipped to give a feeling of being at home while away from home. Hotel amenities: AM/FM Alarm Clock, Bar/Lounge, Business Center, Concierge, 24 Hour Front Desk, Mini Bar, Modem Lines in Room, Meeting/Banquet Facilities, No Smoking Rooms/Facilities, RV or Truck Parking, Restaurant, Room Service Safe Deposit Box, Television with Cable, Laundry/Valet Services. HOTEL GRAND VISCONTI PALACE**** Viale Isonzo 14 Milan http://www.grandviscontipalace.com/ Tel: +39 02 540 341 Fax: +39 02 540 69 523 E-mail [email protected] The Grand Visconti is a fashionable palace in the heart of Italy’s fashion capital. The hotel has 162 rooms of the Classic, Quality and Exclusive type, and 10 Suites ranging from the Junior Suites to the Tower Suite. While the bedrooms are classical, many of the suites have been given touches of a slight minimalist design, for tastes which are sophisticated but not traditional. The hotel has 4 Junior Suites, 3 Executive Suites, 2 Grand Suites and the exclusive Tower Suite. Guests can enjoy an array of amenities including health spa and sauna, indoor swimming pool and express check-in/out. HOTEL LIBERTY**** Viale Bligny 56 Milano http://www.liberty.hotelsinmilan.it Tel: + 39 02 58318562 Fax +39 02 58319061 E-mail [email protected] A newly built deluxe hotel at 10 minutes from city center. -

Comune.Milano.It/Municipio9

comune.milano.it/municipio9 DENOMINAZIONE INDIRIZZO (Via, NUMER Note Quartiere SERVIZIO SVOLTO Orari garantiti Telefono 1 Telefono 2 Mail SOCIALE P.zza) O CIVICO (Facoltativo) servizio in convenzione con diapason assistenza domiciliare anziani e 7-18 da lunedì a il comune di cooperativa sociale municipio 9 disabili sabato 3333992104 [email protected] milano diapason confezionamento e distribuzione 9-13 da lunedì a cooperativa sociale municipio 9 via santa monica 4 alimenti venerdi 3333992104 [email protected] raccolta bisogni dai cittadini allo servizio in 020202 e servizi di convenzione con diapason accompagnamento, consegna pasti 9-16 da lunedì a il comune di cooperativa sociale municipio 9 vpiazza bruzzano e medicinali venerdi 20202 milano Servizio Spesa e farmaci: dalle 9 alle 16 - supporto servizio svolto Spesa a domicilio, consegna ricette psicologico attivo operatrici WeMi Elisa con operatori con Cooperativa Cascina e farmaci con Milano Aiuto. nei giorni : martedì Mussari e Celeste responsabile richiesta Biblioteca/ WeMi Niguarda Affori Supporto psicologico telefonico con mecoledì venerdì Bressi T. servizio: Monica Villa [email protected]; contributo Ornato Dergano Via Luigi Ornato 7 psicologo dedicato. dalle 9 alle 16. 3401113392 T. 342.3302952 [email protected] nell'ordine di €5 via Casoria (sede dal lunedì al Cooperativa Cascina su tutto in legale servizio di assistenza domiciliare venerdì dalle 9 alle Sonia Zaffaroni T. Biblioteca Municipio 9 cooperativa) 50 Anziani. 17 340.6119986 [email protected] -

Fashion (RH) (1837)

TesioPower jadehorse Fashion (RH) (1837) Marske ECLIPSE Spilletta 12 MERCURY TARTAR Tartar Mare Sister To Mogul Mare Gohanna (1790) TARTAR HEROD Cypron 26 Herod Mare MATCHEM Golumpus (1802) Teresa Brown Regulus HEROD TARTAR WOODPECKER Cypron 26 Miss Ramsden CADE Catherine (1795) Lonsdale Mare TRENTHAM Gower's Sweepstakes Camilla Miss South 5 Catton (1809) HIGHFLYER HEROD 26 Delpini Rachel 13 Countess Timothy (1794) Cora Lucy Gray (1804) Crofts Partner TARTAR Meliora HEROD Blaze Cypron Salome Phoenomenon (1780) Marske ECLIPSE Spilletta 12 Frenzy Engineer Engineer Mare Blank Mare Trustee (1829) Marske ECLIPSE Spilletta 12 Pot 8 O'S Sportsman Sportsmistress Golden Locks Waxy (1790) TARTAR HEROD Cypron 26 Maria SNAP 1 Lisette Miss Windsor Whisker (1812) MATCHEM Conductor Snap Mare 12 Trumpator Squirrel BRUNETTE Dove Penelope (1798) HEROD 26 HIGHFLYER Rachel 13 Prunella SNAP 1 Promise Julia Emma (1824) ECLIPSE Marske MERCURY Spilletta 12 Tartar Mare TARTAR Hermes (1790) Sister To Mogul Mare WOODPECKER HEROD 26 Rosina Miss Ramsden 1 Gibside Fairy (1811) Petworth Imperator Pipator Squirrel BRUNETTE Dove Vicissitude (1800) HIGHFLYER 13 Sir Peter Papillon 3 Beatrice MATCHEM Pyrrha Duchess 7 TARTAR Fashion (RH) (1837) HEROD Cypron 26 Florziel Cygnet Cygnet Mare Young Cartouch Mare Diomed (1777) Crab Spectator PARTNER MARE Sister To Juno BLANK Horatia Sister One To Steady SIR ARCHY (1805) HEROD 26 HIGHFLYER Rachel 13 Rockingham MATCHEM Purity Pratts Old Mare Castianira (1796) Gower's Sweepstakes TRENTHAM Miss South 5 Tabitha Bosphorus Bosphorus Mare -

Annual Report 2017 Fondazione Alta Mane Italia - Annual Report 2017 3

Annual report web version 2017 2 fondazione alta mane italia - annual report 2017 fondazione alta mane italia - annual report 2017 3 Table of Contents Letter from the President 2 01 Identity of Alta Mane Italia The Foundation 04 Why Art? 05 Mission 06 Strategy – The 5 areas of intervention 08 The use of Art in the 5 areas 10 The Stakeholders 12 02 Organisational and Operating Model Governance & Staff 14 Management model 15 Project selection process 16 Selection criteria 17 Operational modalities 18 03 Activities and Projects 2017 Annual activities - Projects 20 2017 in summary 21 Workshop locations – Abroad 22 Workshop locations – Italy 23 Focus 2017 Festival x Igual Bariloche, Argentina 24 Projects: Category index 27 Testimonials 70 04 Economic and financial results 2017 Excerpt from Balance Sheet 2017 71 Legal Information 72 N.B. la versione web del Rapporto differisce da quella cartacea ESCLUSIVAMENTE per la numerazione delle pagine. 4 fondazione alta mane italia - annual report 2017 Letter from the President During the course of 2017, drawing up the Foundation’s Three-year Strategic Plan 2018-2020 (TSP) provided the opportunity to analyse for the first time the results obtained in the previous five years of AMI activity, both in quantitative and qualitative terms, as well as to initiate a profound reflection into the merits of the medium to long-term strategic objectives to be sought, with the primary aim of offering young people the benefits of best practices in this sector to enable them to participate in an advantageous change in their social context with the necessary monitoring and possible measuring of results in line with the important changes taking place in the Third Sector. -

Ai Margini Dello Sviluppo Urbano. Uno Studio Su Quarto Oggiaro Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale

Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano. Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale To cite this version: Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale. Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano. Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro: On the Fringes of Urban Development. A Study on Quarto Oggiaro. Bruno Mondadori Editore, pp.192, 2009. hal-01495479 HAL Id: hal-01495479 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01495479 Submitted on 25 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 1 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 2 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 1 Ricerca 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 2 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 3 Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro a cura di Rossana Torri e Tommaso Vitale Bruno Mondadori 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 4 Il volume è finanziato da Acli Lombardia. Tutti i diritti riservati © 2009 Pearson Italia, Milano-Torino Prima pubblicazione: dicembre 2009 Per i passi antologici, per le citazioni, per le riproduzioni grafiche, cartografiche e fotografiche appartenenti alla proprietà di terzi, inseriti in quest’opera, l’editore è a disposizione degli aventi diritto non potuti reperire nonché per eventuali non volute omissioni e/o errori di attribuzione nei riferimenti. -

Il Futuro Della Valle Dei Monaci Allegato

Osservatorio per lo studio e la valorizzazione dei territori attraversati dai percorsi lenti Il futuro della Valle dei Monaci Proposte per l’Amministrazione Comunale di Milano e la Città Metropolitana milanese da parte delle Associazioni della Rete Valle dei Monaci Allegato “A” Relazione estesa Milano, luglio 2018 1 Il futuro della Valle dei Monaci: Proposte per l’Amministrazione comunale di Milano e la Città metropolitana milanese da parte delle Associazioni della Rete Valle dei Monaci. Premessa Questo documento vuole fornire alle Amministrazioni competenti e a tutti gli attori del territorio della Valle dei Monaci un supporto di analisi e di proposte per un possibile “Piano d’Area” orientato agli obiettivi di integrazione urbana, territoriale, sociale ed economica. Tali obiettivi sono già perseguiti nell’azione quotidiana degli attuali soggetti costituenti la Rete Valle dei Monaci, i quali ritengono che la loro quotidiana azione necessiti, a questo punto, anche di un impegno pubblico più deciso per questo territorio che, dopo lunghi decenni di indeterminazione e di degrado, ha cominciato a muoversi verso nuove e promettenti direzioni di sviluppo. Prima di dettagliare i temi ritenuti importanti per il Piano d’Area è però necessario trattare due punti prioritari: 1) spiegare che cos’è la Valle dei Monaci; 2) riportare, spiegandoli brevemente, i progetti pubblici e privati che già interessano il territorio del sud-Milano; ovverosia quelli che già intervengono direttamente sul destino della Valle dei Monaci e quelli di contesto urbano più ampio che sono destinati a influire sulle dinamiche locali. Il presente documento non ha pretese di essere esaustivo e può essere integrato in qualsiasi momento, sia da parte dei proponenti che da parte delle Amministrazioni, se queste lo riterranno una base utile per il loro lavoro. -

Novembre 2012

Numero a 20 pagine &% % ! "# ! "#'"#!$"'' GIORNALE DELL’ASSOCIAZIONE MILANOSUD ·ANNO XVI NUMERO 11 NOVEMBRE 2012· VISITATECI SU WWW.MILANOSUD.IT · INCONTRIAMOCI SU WWW.FACEBOOK.COM GRUPPO MILANOSUD I fallimenti delle società di Ligresti e il destino del Cerba bloccano lo sviluppo della zona ALL’INTERNO Elezioni: Il futuro tra le carte bollate Amianto in via Russoli Il balletto L’assessore De Cesaris: «La partita urbanistica si gioca in tribunale» 4 Bufera sull’Aler: delle date nsomma: «Ligresti e le società del suo gruppo erano un problema intervista a Carmela Rozza per il Comune quando erano in salute e lo sono anche adesso che 5 resto si voterà per il rinnovo del gover- Iin parte sono fallite». Con queste parole, che ben riassumono lo Ancora fumi nocivi Pno della Lombardia. E anche di quello spirito dell’intera serata, l’assessore all’Urbanista Lucia De Cesaris dalla via Selvanesco del Lazio. E anche per il rinnovo del Parla- ha concluso l’incontro pubblico che si è tenuto il 23 ottobre scorso, 7 mento. Nel frattempo si è votato per il con- presso il Consiglio di Zona 5, per illustrare la situazione proprietaria siglio regionale siciliano. In questa se- dei numerosi immobili che il gruppo di Ligresti possiede nella parte Speciale Primarie quenza ravvicinata di turni elettorali, sud della città. del centrosinistra quello siciliano è l’unica certezza, proprio Un incontro che ha visto la partecipazione di tanti cittadini e 8 perché è già avvenuto. consiglieri: tutti desiderosi di conoscere come si svilupperà la Per le altre consultazioni - Lombardia, La- nostra zona. Per questo l’assessore non si è limitata al tema del- Utilizzi sociali zio, Parlamento - tutte e tre imminenti e la serata, ma ha affrontato anche altri nodi cruciali, che da tem- dei beni confiscati alla mafia tutte e tre forzate da scadenze di legge, re- po attendono di essere sciolti. -

Porta Romana Railway Yard: Updated Masterplan and Winter Olympic Village 2026 Unveiled

PORTA ROMANA RAILWAY YARD: UPDATED MASTERPLAN AND WINTER OLYMPIC VILLAGE 2026 UNVEILED SKIDMORE, OWINGS & MERRILL REVEALED AS ARCHITECTS FOR THE OLYMPIC VILLAGE • The Parco Romana masterplan, approved by the Supervisory Board of the Railway Stations Program Agreement, reflects suggestions received during the public consultation • The Masterplan and the Olympic Village are aligned with the parameters of the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan • The Village for Athletes, which will be delivered in July 2025, will have an open architecture that will allow permeability and integration with the surrounding area • The Village, with zero environmental impact, will be a blueprint for ESG- focused developments and, thanks to public/private collaboration, is designed to take into consideration usage requirements both during and after the competition • Timeline of the project is on track Milan, 15 July 2021 - The "Porta Romana" real estate investment fund - promoted and managed by COIMA SGR and subscribed by Covivio, Prada Holding and the COIMA ESG City Impact fund - in agreement with the FS Italiane Group and as auctioneer of the international competition for the preparation of the preliminary masterplan for the regeneration of the Porta Romana railway yard, prepared according to the guidelines of the Municipality of Milan, presents the updated Masterplan of the Railway Yard and the project for the Olympic Village, assigned to Skidmore, Owings & Merrill - SOM. The projects were unveiled today at a press conference attended by the President -

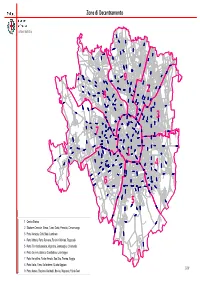

Impagin 9 Zone

Zone di Decentramento Settore Statistica V i a C o m a s i n a V ia V l i e a R u G b . ic o P n a e s t a i t s e T . F e l a i V ani V gn i odi a ta M . Lit L A . Via V ia O l r e n E a . t F o e r V m i a i A s t e s a a n z i n orett i Am o Via C. M e l a i V V V i i a V a i B a M G o . v . L i B s . e a a G s s r s c d a o e s a r n s B i a . F ia V i t s e T V . V F i a a v i ado a l e P l ia e V P a i e E l . V l e F g e r r i n m o i V ia R o M s am s b i r et ti Piazza dell'Ospedale Maggiore a a v z o n n a o lm M a P e l ia a i V V a v Via V o G i d all a a ara ni P te B ia a o nd i a V v . C i G s ia V a V ia s A c a p a e l p i e C n n a in i i V V ia G al V V lar i i at ia hini a e V mbrusc Piazza h V i Via La C c V a r i a C Bausan . -

Le Grandi Chiese

guida cittàdella Comune di Milano Realizzazione editoriale a cura di Settore Politiche del Turismo Iniziative Speciali e Marketing Territoriale di De Agostini Libri S.p.A. Via Dogana, 2 20121 Milano Direttore Andrea Pasquino Direttore Massimiliano Taveggia Product Manager Licia Triberti, Davide Gallotti Servizio sviluppo e monitoraggio del turismo Progetto editoriale Sergio Daneluzzi Federica Savino Servizio portale di promozione Redazione e ricerca iconografica del territorio Marco Torriani Patrizia Bertocchi con Alessandra Allemandi Supervisione dei contenuti Progetto grafico e impaginazione Mauro Raimondi Sandra Luzzani con Vando Pagliardini Testi a cura di Monica Berno Servizi Tecnici Prepress Andrea Campo Coordinamento tecnico Guido Leonardi Scarica l’App “Milano. Guida della Città” per: All’interno della Guida, attiva i QR code sul tuo smartphone: presenti in ogni itinerario, ti consentiranno di accedere ai contenuti speciali della Guida. Crediti fotografici DeAgostini Picture Library, Archivio Alinari, Alessandro Casiello, Marco Clarizia, Contrasto, Corbis, Gianni Congiu, Marka, Mauro Ranzani, Andrea Scuratti, Vando Pagliardini, Michela Veicsteinas Aggiornamento dicembre 2015 sommario Introduzione 2 Mappa della città/Centro della città 4 Milano e la sua Storia 8 1 A spasso per il Centro 10 2 Antica Roma e Medioevo 12 3 Il Rinascimento e il Barocco 14 4 Il Neoclassico e l’Ottocento 16 5 Le Grandi Chiese di Milano 18 6 I Palazzi di Milano 22 7 I Musei di Milano 26 8 Arte Contemporanea a Milano 30 9 La Milano delle Scienze 36 10 Parchi e Navigli 38 11 Shopping a Milano 42 12 Spettacoli, Sport e Divertimento 44 13 Oltre Milano 46 Informazioni Utili 48 Benvenuti Una grande città ha bisogno di uno sguardo d’insieme: ecco una guida maneggevole e completa, una porta di accesso ai tesori di bellezza di Milano e del suo territorio. -

Nuclei Di Identita' Locale (NIL)

Schede dei Nuclei di Identità Locale 3 Nuclei di Identita’ Locale (NIL) Guida alla lettura delle schede Le schede NIL rappresentano un vero e proprio atlante territoriale, strumento di verifica e consultazione per la programma- zione dei servizi, ma soprattutto di conoscenza dei quartieri che compongono le diverse realtà locali, evidenziando caratteri- stiche uniche e differenti per ogni nucleo. Tale fine è perseguito attraverso l’organizzazione dei contenuti e della loro rappre- sentazione grafica, ma soprattutto attraverso l’operatività, restituendo in un sistema informativo, in costante aggiornamento, una struttura dinamica: i dati sono raccolti in un’unica tabella che restituisce, mediante stringhe elaborate in linguaggio html, i contenuti delle schede relazionati agli altri documenti del Piano. Si configurano dunque come strumento aperto e flessibile, i cui contenuti sono facilmente relazionabili tra loro per rispondere, con eventuali ulteriori approfondimenti tematici, a diverse finalità di analisi per meglio orientare lo sviluppo locale. In particolare, le schede NIL, come strumento analitico-progettuale, restituiscono in modo sintetico le componenti socio- demografiche e territoriali. Composte da sei sezioni tematiche, esprimono i fenomeni territoriali rappresentativi della dinamicità locale presente. Le schede NIL raccolgono dati provenienti da fonti eterogenee anagrafiche e censuarie, relazionate mediante elaborazioni con i dati di tipo geografico territoriale. La sezione inziale rappresenta in modo sintetico la struttura della popolazione residente attraverso l’articolazione di indicatori descrittivi della realtà locale, allo stato di fatto e previsionale, ove possibile, al fine di prospettare l’evoluzione demografica attesa. I dati demografici sono, inoltre, confrontati con i tessuti urbani coinvolti al fine di evidenziarne l’impatto territoriale.