Italy Case Study Report 2: Milan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volantino SAD Anziani.Pub

CHI SIAMO Fondazione Aquilone Onlus rappresenta Fondazione Aquilone ha maturato una l’ideale continuazione e sviluppo consolidata esperienza nella gestione di servizi dell’esperienza dell’associazione di V.S.P. per persone anziane in convenzione o www.fondazioneaquilone.org Bruzzano Onlus (Volontari Sostegno collaborazione con il Comune di Milano: Persona). In oltre 25 anni di attività, grazie Servizio Custodi Sociali nei quartieri di anche all’intensificarsi dei rapporti con le Bruzzano, Comasina, Bovisasca e Riguarda. istituzioni locali (Comune, Provincia, Estate amica - pronto intervento estivo, nei Regione, ASL, Scuole), è stato possibile dare quartieri di Affori, Bruzzano e Comasina. alcuni contributi significativi alla Interventi di assistenza domiciliare privata o SERVIZIO realizzazione di comunità locali attente alla tramite "buono sociale" del Comune qualità di vita di alcuni quartieri (Bruzzano, Comasina, Bovisasca, Città studi). La Tenda - un servizio di prossimità e socialità "per e con" gli anziani in Città Studi ASSISTENZA I punti di forza e di qualità dei servizi e dei progetti di Fondazione Aquilone, che hanno Inoltre gestisce servizi e progetti rivolti a saputo inserirsi nel contesto dei diversi Piani famiglie, bambini, adolescenti, giovani, disabili. DOMICILIARE di zona della Città, sono: prossimità e Ulteriori informazioni su Internet all’indirizzo solidarietà ben radicate in alcuni quartieri www.fondazioneaquilone.org della zona 9; prendersi cura di chi vive per persone anziane momenti di fragilità; passione di educare condivisa con le persone e le famiglie DOVE SIAMO percepite partner nei processi educativi e sociali e non semplice utenti di servizi; animazione di comunità e lavoro di rete con Servizio accreditato con le istituzioni e le diverse risorse del Fondazione Aquilone Onlus SERVIZIO ASSISTENZA DOMICILIARE territorio; flessibilità e personalizzazione degli interventi; sinergia tra operatori e piazza Bruzzano 8 Milano Il sistema dell’accreditamento, volontari . -

Comune.Milano.It/Municipio9

comune.milano.it/municipio9 DENOMINAZIONE INDIRIZZO (Via, NUMER Note Quartiere SERVIZIO SVOLTO Orari garantiti Telefono 1 Telefono 2 Mail SOCIALE P.zza) O CIVICO (Facoltativo) servizio in convenzione con diapason assistenza domiciliare anziani e 7-18 da lunedì a il comune di cooperativa sociale municipio 9 disabili sabato 3333992104 [email protected] milano diapason confezionamento e distribuzione 9-13 da lunedì a cooperativa sociale municipio 9 via santa monica 4 alimenti venerdi 3333992104 [email protected] raccolta bisogni dai cittadini allo servizio in 020202 e servizi di convenzione con diapason accompagnamento, consegna pasti 9-16 da lunedì a il comune di cooperativa sociale municipio 9 vpiazza bruzzano e medicinali venerdi 20202 milano Servizio Spesa e farmaci: dalle 9 alle 16 - supporto servizio svolto Spesa a domicilio, consegna ricette psicologico attivo operatrici WeMi Elisa con operatori con Cooperativa Cascina e farmaci con Milano Aiuto. nei giorni : martedì Mussari e Celeste responsabile richiesta Biblioteca/ WeMi Niguarda Affori Supporto psicologico telefonico con mecoledì venerdì Bressi T. servizio: Monica Villa [email protected]; contributo Ornato Dergano Via Luigi Ornato 7 psicologo dedicato. dalle 9 alle 16. 3401113392 T. 342.3302952 [email protected] nell'ordine di €5 via Casoria (sede dal lunedì al Cooperativa Cascina su tutto in legale servizio di assistenza domiciliare venerdì dalle 9 alle Sonia Zaffaroni T. Biblioteca Municipio 9 cooperativa) 50 Anziani. 17 340.6119986 [email protected] -

Project Via Visconti Di Modrone

PROJECT VIA VISCONTI DI MODRONE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY IN MILAN 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS Potential of the investment opportunity The Report is divided into 3 parts: • a market analysis involving macroeconomic data and a specific focus on the area; • A comparable and case study analysis; • A business plan with internal assumptions. The property under analysis, sited in Via Visconti di Modrone , in an upper floor of a fashionable eighties building. The investment purpose is to acquire the asset and convert it into residential. The exit strategy foresees a fractioned sale of the residential units, which will be split among a 44 sqm studio, a 41 sqm studio and a 54 sqm apartment. Via Visconti di Modrone is in San Babila, one of the best district of Milan, which is in turn considered by most the economic capital of Italy, where both the employment level and the average income are both above the Italian level. The investment opportunity results interesting, displaying an unlevered IRR of 19.85% and a net equity IRR of 24.08%. The results of a sensitivity analysis in which we varied the sale price/sqm and the average sale time show that the net equity IRR turns negative in case of low-end sale price scenarios (6,800 €/sqm). This is mainly due to the assumption of ca. 1,200 €/sqm of renovation costs. However, high renovation costs allow to obtain top-quality products, therefore diminishing the likelihood of low-range sale prices. 3 INDEX 1. Macroeconomic Outlook page 5 2. Comparables page 11 3. Investment Evaluation page 14 4 1. -

Ai Margini Dello Sviluppo Urbano. Uno Studio Su Quarto Oggiaro Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale

Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano. Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale To cite this version: Rossana Torri, Tommaso Vitale. Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano. Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro: On the Fringes of Urban Development. A Study on Quarto Oggiaro. Bruno Mondadori Editore, pp.192, 2009. hal-01495479 HAL Id: hal-01495479 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01495479 Submitted on 25 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 1 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 2 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 1 Ricerca 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 2 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 3 Ai margini dello sviluppo urbano Uno studio su Quarto Oggiaro a cura di Rossana Torri e Tommaso Vitale Bruno Mondadori 00Quarto Oggiaro romane_PBM 10/11/09 10.36 Pagina 4 Il volume è finanziato da Acli Lombardia. Tutti i diritti riservati © 2009 Pearson Italia, Milano-Torino Prima pubblicazione: dicembre 2009 Per i passi antologici, per le citazioni, per le riproduzioni grafiche, cartografiche e fotografiche appartenenti alla proprietà di terzi, inseriti in quest’opera, l’editore è a disposizione degli aventi diritto non potuti reperire nonché per eventuali non volute omissioni e/o errori di attribuzione nei riferimenti. -

Nota Stampa DAL 5 AL 19 AGOSTO PER LAVORI ALLA RETE FERROVIARIA SOSPESA LA CIRCOLAZIONE FRA MILANO BOVISA E MILANO LANCETTI I Tr

Nota stampa DAL 5 AL 19 AGOSTO PER LAVORI ALLA RETE FERROVIARIA SOSPESA LA CIRCOLAZIONE FRA MILANO BOVISA E MILANO LANCETTI I treni della linea S1 circoleranno fra Lodi e Milano Porta Vittoria La linea S13 avrà destinazione alternativa a Milano Certosa Informazioni sul sito trenord.it e su App Trenord Milano, 3 agosto 2018 – Da domenica 5 a domenica 19 agosto per consentire lo svolgimento di lavori di competenza del gestore dell’infrastruttura FerrovieNord a Milano Bovisa i treni non circoleranno fra le stazioni di Milano Bovisa e Milano Lancetti. Per questo la circolazione delle linee S1 Saronno-Milano Passante-Lodi e S13 Milano Bovisa-Pavia nel periodo citato subirà alcune modifiche. S1 Saronno-Milano Passante-Lodi I treni circoleranno regolarmente tra Milano Porta Vittoria e Lodi; non effettueranno servizio fra Milano Porta Vittoria e Milano Bovisa. I viaggiatori diretti a Saronno potranno utilizzare da Milano Cadorna i treni delle linee regionali per Como Lago, Novara Nord, Laveno, Malpensa Aeroporto e della linea S3 Saronno-Milano Cadorna. Non saranno effettuate le corse di collegamento fra Milano Rogoredo e Milano Bovisa: 23204 (Milano Rogoredo 5.57-Milano Bovisa 6.24); 23239 (Milano Bovisa 10.06-Milano Rogoredo 10.33); 23251 (Milano Bovisa 11.06-Milano Rogoredo 11.33); 23252 (Milano Rogoredo 11.27-Milano Bovisa 11.54); 23264 (Milano Rogoredo 12.27-Milano Bovisa 12.54). La corsa 23201 (Milano Rogoredo 5.35-Lodi 6.07) circolerà regolarmente. S13 Milano Bovisa-Pavia I treni circoleranno regolarmente tra Pavia e Milano Lancetti; da lì, raggiungeranno la destinazione alternativa di Milano Certosa, effettuando fermata a Villapizzone. -

MILANO Tra Ferrovie E Metropolitana! S8 S9 S11 Tram, Autobus, Filobus E Servizi Di Bike E Car Sharing

Far funzionare questo sistema urbano è molto complesso e così il sistema Bicicletta della mobilità è composto non solo da ferrovie e metropolitana, ma anche È il mezzo migliore per spostarsi a Milano, ti conviene comprarne una MILANO tra ferrovie e metropolitana! S8 S9 S11 tram, autobus, filobus e servizi di bike e car sharing. appena possibile. Ti tieni in allenamento, rispetti l’ambiente e entrarai a far parte di una comunità ciclistica intrepida, a cui il traffico folle di M1 SESTO I° MAGGIO (FS) Sul sito dell’ATM potrai cercare il tuo percorso (www.atm-mi.it), oppure Milano non fa paura! Ah ricorda che proprio vicino a Piazza Leonardo si Milano è una città di 1.300.000 abitanti e durante il giorno, grazie ai flussi per ulteriori informazioni chiama il numero verde: 800.80.81.81 attivo tutti trova la leggendaria ciclofficinaruotalibera! Cercala on line e potrai in ingresso della popolazione pendolare, non è difficile immaginare che SESTO RONDÒ i giorni, dalle 7.30 alle 19.30. riparare la tua bici comodamente e incontrare un sacco di studenti in arrivi oltre i 2 milioni. La città per ragioni di gestione è stata suddivisa in gamba come te! parti, le cosiddette “Zone”. La sede di Bovisa del Politecnico di Milano fa (BIGNAMI) (www.ciclofficinaruotalibera.wordpress.com) parte della Zona 9, mentre la sede di Leonardo (Piola) SESTO MARELLI S2 S4 è calata nel contesto della Zona 3. M3 BRUZZANO COMASINA VILLA S. GIOVANNI Greco AFFORI CENTRO M2 PRECOTTO COLOGNO NORD QUARTO OGGIARO AFFORI (FN) DERGANO COLOGNO CENTRO GORLA MACIACHINI BOVISA COLOGNO SUD VIMODRONEC.NA BURRONACERNUSCO VILLA FIORITACASSINA DE' BUSSEROPECCHI VILLA POMPEAGORGONZOLAC.NA ANTONIETTAGESSATE RHO RHO-FIERA MILANO CERTOSA ZARA TURRO C.NA GOBBA VILLAPIZZONE S2 S10 M2 M1 LANCETTI RROVERETOovereto CRESCENZAGO SONDRIO S. -

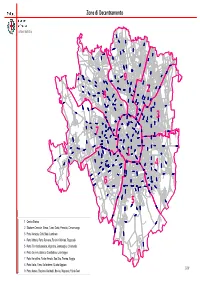

Impagin 9 Zone

Zone di Decentramento Settore Statistica V i a C o m a s i n a V ia V l i e a R u G b . ic o P n a e s t a i t s e T . F e l a i V ani V gn i odi a ta M . Lit L A . Via V ia O l r e n E a . t F o e r V m i a i A s t e s a a n z i n orett i Am o Via C. M e l a i V V V i i a V a i B a M G o . v . L i B s . e a a G s s r s c d a o e s a r n s B i a . F ia V i t s e T V . V F i a a v i ado a l e P l ia e V P a i e E l . V l e F g e r r i n m o i V ia R o M s am s b i r et ti Piazza dell'Ospedale Maggiore a a v z o n n a o lm M a P e l ia a i V V a v Via V o G i d all a a ara ni P te B ia a o nd i a V v . C i G s ia V a V ia s A c a p a e l p i e C n n a in i i V V ia G al V V lar i i at ia hini a e V mbrusc Piazza h V i Via La C c V a r i a C Bausan . -

Nuclei Di Identita' Locale (NIL)

Schede dei Nuclei di Identità Locale 3 Nuclei di Identita’ Locale (NIL) Guida alla lettura delle schede Le schede NIL rappresentano un vero e proprio atlante territoriale, strumento di verifica e consultazione per la programma- zione dei servizi, ma soprattutto di conoscenza dei quartieri che compongono le diverse realtà locali, evidenziando caratteri- stiche uniche e differenti per ogni nucleo. Tale fine è perseguito attraverso l’organizzazione dei contenuti e della loro rappre- sentazione grafica, ma soprattutto attraverso l’operatività, restituendo in un sistema informativo, in costante aggiornamento, una struttura dinamica: i dati sono raccolti in un’unica tabella che restituisce, mediante stringhe elaborate in linguaggio html, i contenuti delle schede relazionati agli altri documenti del Piano. Si configurano dunque come strumento aperto e flessibile, i cui contenuti sono facilmente relazionabili tra loro per rispondere, con eventuali ulteriori approfondimenti tematici, a diverse finalità di analisi per meglio orientare lo sviluppo locale. In particolare, le schede NIL, come strumento analitico-progettuale, restituiscono in modo sintetico le componenti socio- demografiche e territoriali. Composte da sei sezioni tematiche, esprimono i fenomeni territoriali rappresentativi della dinamicità locale presente. Le schede NIL raccolgono dati provenienti da fonti eterogenee anagrafiche e censuarie, relazionate mediante elaborazioni con i dati di tipo geografico territoriale. La sezione inziale rappresenta in modo sintetico la struttura della popolazione residente attraverso l’articolazione di indicatori descrittivi della realtà locale, allo stato di fatto e previsionale, ove possibile, al fine di prospettare l’evoluzione demografica attesa. I dati demografici sono, inoltre, confrontati con i tessuti urbani coinvolti al fine di evidenziarne l’impatto territoriale. -

Translation Rights / Fall 2020

Translation Rights / Fall 2020 Simonetta Agnello Hornby / Sibilla Aleramo / Eleonora Marangoni / Agnese Codignola / Paolo Settis / Franco Baresi / Guido Tonelli / Paolo Sorrentino / Silvia Ferrara / Giovanni Testori / Giuseppina Torregrossa / Boris Pasternak / Tomasi Di Lampedusa / Luce D’Eramo / Alessandro Vanoli / Gad Lerner / Barbara Fiorio / Stefano Benni / Francesco Stoppa / Arianna Cecconi / Marco D’Eramo / Massimo Recalcati / Federica Brunini SIMONETTA AGNELLO HORNBY Fiction © Dario Canova SIMONETTA AGNELLO HORNBY Piano nobile / Piano nobile was born in Palermo but has been living Palermo, summer 1942. On his deathbed, the Baron Enrico Sorci in London since 1972 where she worked sees the recent history of his family pass before his eyes, as in a lucid as a solicitor for the community legal delirium. He sees the devotion of his wife, his daughters (Maria aid firm specialized in domestic violence Teresa, Anna and Lia) and his sons (Cola, Ludovico, Filippo and that she co-founded in 1979. She has Andrea), at the same time he sees the destiny of a city that, at the been lecturing for many years, and was a turn of the century, is full of opportunities and new wealth and of part-time judge at the Special Educational trains passing by loaded with goods. Needs and Disability Tribunal for eight Before dying, the baron orders to wait before announcing his passing. years. Her novels: La zia marchesa (2004), His relatives therefore gather around the large table in the dining Boccamurata (2007), Vento scomposto room for a crowed symposium held amidst silence, twinkles, tensions, (2009), La Monaca (2010), La cucina del squabbles, ancient rivalries and new ambitions. -

Moving in Milan from Bovisa Station to Department of Energy

Moving in Milan from Bovisa station to Department of Energy 1. Go out of the station 2. Turn right and take the ladder 3. Cross the car parking and go towards the B25 building from Milano Malpensa to Bovisa Politecnico 1. Take the Malpensa Express till Bovisa Politecnico 2. The train continues towards Milano Centrale or Milano Cadorna TICKETS NEEDED • 1 TreNord ticket to Malpensa (12€) from Milano Linate to Bovisa Politecnico 1. Take the Air Bus till Milano Centrale. After 6:15 a.m., there is an Air Bus every 30 minutes till 20:15. After 21:00, there is an Air Bus every 30 minutes till 23:00. 3. Follow the direction for Underground green line M2 till Cadorna stop. The underground lines are indicated with a green sign - . 4. At Cadorna, follow the indication to reach the Train Station in the immediate surface out of the underground. 5. Every train which departs from Cadorna, apart for Malpensa Express, stops at Bovisa Train Station (it is the second stop, after “Domodossola”). TICKETS NEEDED • 1 AIR BUS TICKET (5€); you can take the ticket directly on board. • 1 URBANO (1.5€) which allows you to take the train and the underground; from Bergamo Orio al Serio to Bovisa Politecnico 1. Take the Orio Shuttle till Milano Centrale. 2. Follow the direction for Underground green line M2 till Cadorna stop. The underground lines are indicated with a green sign - . 3. At Cadorna, follow the indication to reach the Train Station in the immediate surface out of the underground. 4. Every train which departs from Cadorna, apart for Malpensa Express, stops at Bovisa Train Station (it is the second stop, after “Domodossola”). -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 16, Folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 16, folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 16 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 792 F TO C TATE WA HOC 1233 1 °"'I:::: N ,, I 0 II N ' I . ... ROME 7 480 PA S Ml TE HOUSE l'O, MS • · !? ENFELD E. • lt6~2: AO • E ~4SSIFY 11111~ TA, : ~ IP CFO D, GERALD R~) SJ 1 C I P E 10 NTIA~ VISIT REF& BRU SE 4532 UI INAl.E PAL.ACE U I A PA' ACE, TME FFtCIA~ RESIDENCE OF THE PR!S%D~NT !TA y, T ND 0 1 TH HIGHEST OF THE SEVEN HtL.~S OF ~OME, A CTENT OMA TtM , TH TEMPLES OF QUIRl US AND TME s E E ~oc T 0 ON THIS SITE. I THE CE TER OF THE PR!SENT QU?RINA~ IAZZA OR QUARE A~E ROMAN STATUES OF C~STOR .... -

I Dieci Progetti Della Call for Ideas Del Politecnico Di Milano

A cura di Anna Moro i dieci progetti dellA Call for Ideas del Politecnico di Milano con contributi di Alessandro Balducci, Manuela Grecchi, Gabriele Pasqui, Ilaria Tosoni Progetto grafco Sonia Pravato Impaginazione Elena Acerbi In copertina Gasometri, Bovisa foto di Anna Moro ISBN 978-88-916-2093-4 © Copyright 2017 Maggioli S.p.A. È vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo efettuata, anche ad uso interno e didattico, non autorizzata. Maggioli Editore è un marchio di Maggioli S.p.A. Azienda con sistema qualità certifcato ISO 9001:2008 47822 Santarcangelo di Romagna (RN) • Via del Carpino, 8 Tel. 0541/628111 • Fax 0541/622595 www.maggiolieditore.it e-mail: [email protected] Diritti di traduzione, di memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento, totale o parziale con qualsiasi mezzo sono riservati per tutti i Paesi. Il catalogo completo è disponibile su www.maggioli.it area università Finito di stampare nel mese di marzo 2017 nello stabilimento Maggioli S.p.A Santarcangelo di Romagna (RN) I dieci progetti della Call for Ideas del Politecnico di Milano Andrea Arcidiacono, Jacopo Ascari, Davide Del Curto, Paolo Galuzzi, Federico Ghirardelli, Stefano Ginnari, Giulio Giordano, Matias Gonzalez, Giovanna Longhi, Paolo Mazzoleni, Giacomo Menini, Alessandra Oppio, Alessandro Trevisan, Stefano Pareglio, Alessandro Prandolini, Piergiorgio Vitillo | Guya Bertelli, Alberta Albertella, Gaetano Cascini, Stefano Consonni, Marco Facchinetti, Marino Gatto, Agostino Petrillo, Livio Pinto, Angela Poletti, Michele