Onomastica Uralica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Permit to Erect and Maintain Custom Street Signs On

Permit To Erect & Maintain Custom Street & Traffic Signs On Gwinnett County Street Rights-Of-Way (Revised November 2004) The intent of this permit is to grant (hereinafter called the “maintaining authority”) the authority to erect and maintain traffic signs within the boundaries of that includes the streets named as follows: The maintaining authority is granted the permission to erect and maintain signs of the following types: Street Name Signs Stop Signs and Yield Signs Other Regulatory Signs Other Warning Signs The maintaining authority is granted this permit with the following stipulations: • No cost to Gwinnett County shall arise from the maintenance of these custom signs. • The maintaining authority agrees to indemnify Gwinnett County of any liability incurred by these signs. • In the case of residential subdivisions, the maintaining authority will be the developer and a legally constituted homeowners association mandated by the restrictive covenants. • The restrictive covenants shall contain an express provision referencing the association’s responsibility to erect and maintain signage within the subdivision in accordance with the permit. • The final plat will contain a notice signed by the developer which notifies all property owners of their responsibility for erecting and maintaining signage in the subdivision in accordance with this permit. • Installation of Street Name Signs. All street name sign blades shall be installed on top of traffic control signs (Stop, Yield, etc.) – NO EXCEPTIONS. WDJ: J & X: Custom Traffic Sign Application Form Page 1 of 8 6” Maximum clearance from top of traffic control sign to the bottom of first street name sign. 3” Maximum clearance between street name sign blades. -

1979-02-13 BCC Meeting Minutes

i ;i February 13, 1979 Page 417 In ti Ir Meeting The Board of County Commissioners met in Commission Chambers in the Courthouse 11 11 Opened 1: on Tuesday, February 13, 1979. Commissioners Allen E. Arthur, Jr.; Lamar Thomas; I ! Dick Fischer; Lee Chira and Ed Mason were present. Also present were County 1 i Administrator James Harris, Assistant County Attorney Tom Wilkes and Deputy 1 j /I Clerk Mary Jo Hudson. There being a quorum, the Chai rman cal led the meeting to I/ order at 9:00 a.m. Following the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag, the Board /I f 1 paused for a moment of silent invocation. i! it 1. Upon a motion by Commissioner Fischer, seconded by Commissioner Mason and carried, 1; I; 1 the Board approved the minutes of the meeting of January 23, 24, 25 and 1:- I i1 February 1, 1979, and waived the reading of same. I I I Warrants and Upon a motion duly made, seconded and carried, the following warrants were Vouchers approved by the Board having been certified by the Finance Director that same had not been drawn on overexpended accounts: List # Amoun t Handicapped Chi 1 d Program Head Start Program Victim Advocate Program Spouse Abuse Youth P rograms Rehabi 1 i tat ion Center Green House I I Green House Citizens Dispute Settlement Diversion Project CSA Energy Program Neighborhood Services C. D., Housing Repair CETA I CETA I I CETA I I I YETP CETA VI Child Support Enforcement Program Commun i ty Development , 4th year Commun i ty Deve 1 opmen t , 3 rd year CETA VI Pub1 ic Works Sewer Grant Solid Waste Regular Board Civic Center Fund 53 Self Insurance Fund 58 7th Gas Tax Fund 82 Attorney Upon a mot ion by Commissioner Chi ra, seconded by Commissioner Mason and carried, 1 Payment 1, the Board accepted the recommendations of staff and approved payment of $219.73 ! to Mateer, Harbert, Bechtel & Phal in for attorney costs for the month of 1 January, 1979. -

“Bruno Barbieri 4 Hotel”. Come Cambia Il Mondo Della Neve Ai Tempi

Anno Year 6 n°11 Inverno Winter 2020-2021 OSPITALITÀ HOSPITALITY INVERNO WINTER Campiglio e la Val Rendena Come cambia il mondo della neve campionesse di ospitalità ai tempi del Coronavirus? con “Bruno Barbieri 4 Hotel”. Incognite e prospettive. CAMPIGLIO AND VAL RENDENA HOW ARE WINTER VACATIONS CHANGING CHAMPIONS OF HOSPITALITY FOR IN THESE TIMES OF THE CORONAVIRUS? BRUNO BARBIERI 4 HOTEL. UNCERTAINTY AND THE OUTLOOK. EDITORIALE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Un nuovo tempo DI/BY ALBERTA VOLTOLINI VERRÀ IL TEMPO con l’intervento di autorevoli PER RINCONTRARE firme. Racconta storie di LA MONTAGNA vita e di passione per il D’INVERNO:il fascino lavoro. Segue le tracce di del bianco paesaggio, il avventure imprenditoriali che divertimento dello sci, si nutrono di creatività, arte, l’avventura delle attività design. Dà voce a progetti, New times outdoor, la curiosità delle innovativi e sostenibili, che THE TIME WILL COME TO Until then, #CampiglIO will be nuove esperienze, il calore valorizzano le persone e MEET AGAIN IN THESE keeping the fire going for our dell’accoglienza alpina. fanno bene all'ambiente. SNOWY MOUNTAINS the readers, as we take a closer look Verrà il tempo per tornare ad Presenta la puntata di “Bruno allure of a wintry landscape, the at the light and shadow of the ammirare la bellezza silenziosa Barbieri 4 Hotel”: l’eccellenza thrill of skiing, adventure in the present through the eyes of the della natura vestita di neve. dell’ospitalità e la maestria dei great outdoors, the excitement of experts. In this issue, we tell the Verrà il tempo per disegnare, nostri operatori protagoniste new experiences and the warmth stories of passion for a lifelong di nuovo, sinuose curve sulle dello show tv diventato un cult. -

Heritage, Landscape and Conflict Archaeology

THE EDGE OF EUROPE: HERITAGE, LANDSCAPE AND CONFLICT ARCHAEOLOGY by ROXANA-TALIDA ROMAN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The research presented in this thesis addresses the significance of Romanian WWI sites as places of remembrance and heritage, by exploring the case of Maramureș against the standards of national and international heritage standards. The work provided the first ever survey of WWI sites on the Eastern Front, showing that the Prislop Pass conflictual landscape holds undeniable national and international heritage value both in terms of physical preservation and in terms of mapping on the memorial-historical record. The war sites demonstrate heritage and remembrance value by meeting heritage criteria on account of their preservation state, rarity, authenticity, research potential, the embedded war knowledge and their historical-memorial functions. The results of the research established that the war sites not only satisfy heritage legal requirements at various scales but are also endangered. -

Capital Improvement Plan FY 2018-19 to FY 2022-23

Capital Improvement Plan Fiscal Year 2018-2019 to Fiscal Year 2022-2023 Capital Improvement Plan FY 2018‐19 to FY 2022‐23 City Council Jonathan Ingram, Mayor Alan Long, Mayor Pro Tem Rick Gibbs, Councilmember Randon Lane, Councilmember Kelly Seyarto, Councilmember Kim Summers, City Manager Ivan Holler, Assistant City Manager Stacey Stevenson, Administrative Services Director Jeff Murphy, Development Services Director This Page Left Blank Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Capital Improvement Plan Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 Guide to Reading the CIP Project Detail ....................................................................................................... 8 FINANCIAL SUMMARY Capital Improvement Plan Sources & Uses ................................................................................................... 9 Revenue Sources ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Revenue Schedule ....................................................................................................................................... 19 Capital Improvement Projects by Funding Source ...................................................................................... 23 Unfunded Projects by Category .................................................................................................................. 35 Parameters for Budget Cost Estimates ...................................................................................................... -

IL CAPITALE CULTURALE Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage Supplementi 04 / 2016

IL CAPITALE CULTURALE Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage Supplementi 04 / 2016 eum Il Capitale culturale Marazzi, Fabio Mariano, Aldo M. Morace, Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage Raffaella Morselli, Olena Motuzenko, Giuliano Supplementi 4, 2016 Pinto, Marco Pizzo, Edouard Pommier, Carlo Pongetti, Adriano Prosperi, Angelo R. Pupino, ISSN 2039-2362 (online) Bernardino Quattrociocchi, Mauro Renna, ISBN 978-88-6056-466-5 Orietta Rossi Pinelli, Roberto Sani, Girolamo Sciullo, Mislav Simunic, Simonetta Stopponi, © 2016 eum edizioni università di macerata Michele Tamma, Frank Vermeulen, Stefano Registrazione al Roc n. 735551 del 14/12/2010 Vitali Direttore Web Massimo Montella http://riviste.unimc.it/index.php/cap-cult e-mail Coordinatore editoriale [email protected] Francesca Coltrinari Editore Coordinatore tecnico eum edizioni università di macerata, Centro Pierluigi Feliciati direzionale, via Carducci 63/a – 62100 Macerata Comitato editoriale tel (39) 733 258 6081 Giuseppe Capriotti, Alessio Cavicchi, Mara fax (39) 733 258 6086 Cerquetti, Francesca Coltrinari, Patrizia http://eum.unimc.it Dragoni, Pierluigi Feliciati, Enrico Nicosia, [email protected] Francesco Pirani, Mauro Saracco, Emanuela Stortoni Layout editor Cinzia De Santis Comitato scientifi co - Sezione di beni culturali Giuseppe Capriotti, Mara Cerquetti, Francesca Progetto grafi co Coltrinari, Patrizia Dragoni, Pierluigi Feliciati, +crocevia / studio grafi co Maria Teresa Gigliozzi, Valeria Merola, Susanne Adina Meyer, Massimo Montella, Umberto Moscatelli, Sabina Pavone, -

Anexa La Ordinul Prefectului Nr.83/25.04.2007

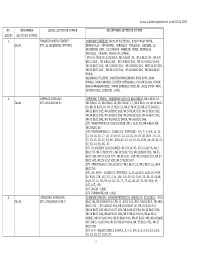

Anexa la Ordinul prefectului nr.83/25.04.2007 NR. DENUMIREA SEDIUL SECŢIEI DE VOTARE DELIMITAREA SECŢIEI DE VOTARE SECŢIEI SECŢIEI DE VOTARE 1. FUNDAŢIA PENTRU TINERET CUPRINDE STRĂZILE: NICOLAE BĂLCESCU, BUDAY NAGY ANTAL, ZALĂU STR: 22 DECEMBRIE 1989 NR.1 BRĂDETULUI, CĂPRIOAREI, CERBULUI, CIREŞULUI, DECEBAL, 22 DECEMBRIE 1989, C.D.GHEREA, MERILOR, MORII, OBORULUI, PARCULUI, PĂDURII, PRUNILOR, STÂNEI, STR GH. DOJA CU BLOCURILE: NR.4 BLOC D4, NR.6 BLOC D6 , NR.6/A BLOC D6/A , NR.8 BLOC.D8 , NR.10 BLOC D10, NR 10/A BLOC D10/A, NR.12 BLOC D12, NR.14 BLOC D14, NR.18 BLOC D18, NR20 BLOC D20 , NR.22 BLOC D22 , NR.24 BLOC D24, NR.26 BLOC D26, NR.26/A BLOC D26/A. ALEXANDRU FILIPIDE , DUMITRU MĂRGINEANU, EMIL BOTA ,IOAN MANGO, IOAN CARAION, LEONTIN GHERGARIU , LUCIAN BLAGA, MIRON RADU PARASCHIVESCU, MARIN SORESCU, NICOLAE LABIŞ ,PETRI MOR , SIMION OROS, SZIKSZAI LAJOS. 2. CĂMIN DE COPII NR.1 CUPRINDE STRADA: GHEORGHE DOJA CU BLOCURILR: NR.1 BLOC 14, ZALĂU STR. GH.DOJA NR.19 NR.3 BLOC 15, NR.5 BLOC 16, NR.7 BLOC 17, NR.9 BLOC 18, NR.11 BLOC 19, NR.13 BLOC 20, NR.15 BLOC 21, NR.17 BLOC 22, NR.23 BLOC D23, NR.25 BLOC D25, NR.28 BLOC D28, NR.30 BLOC D30, NR.32 BLOC D32, NR.34 BLOC D34, NR.36 BLOC D36, NR.38 BLOC D38, NR.40 BLOC D40, NR.42 BLOC D42, NR. 42/A BLOC D42/A, NR.48 BLOC D48. STR. MIHAI EMINESCU CU BLOCURILE :NR.2 BLOC E2, NR.4 BLOC E4, NR.6 BLOC E6. -

Font Design for Street Name Signs

PennDOT LTAP technical INFORMATION SHEET Font DesigN for Street Name SIgns #174 The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has terminated its approval of the Clearview Highway font, summer/2016 which PennDOT had specified as the standard font for freeway guide signs and conventional highway street name signs. Standard Alphabets for Traffic Control Devices, more commonly referred to as Highway Gothic, is now the only approved font for the design of traffic signs. FHWA has not issued a mandate on the replacement of signs using the Clearview font, but all future sign installations are to use the Highway Gothic font. This means existing signs may remain in use for their normal service life but should be replaced with a sign using Highway Gothic, when appropriate, as part of routine maintenance. Highway Gothic is a modified version of the standard Gothic font and was originally developed in the late 1940s by the California Department of Transportation. The font has six configurations known as letter series (B, C, D, E, E (modified), and F). Each series increasingly widens the individual letter sizing and expands the spacing between the letters. D3-1 street name sign with Street name signs (D3-1) and most other guide signs must be Highway Gothic font. designed separately because of variability in the message or legend that limits the ability to standardize sizes. PennDOT Publication 236, Handbook of Approved Signs, provides the minimum requirements for street name signs (D3-1). Additionally, the 2009 Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) states that letters used on street name signs (D3-1) must be composed of a combination of lowercase letters with initial uppercase letters. -

Lifting the Veil of the Borderscape

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasd fghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLifting the veil of the borderscape A phenomenological research on lived wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiexperience and societal processes in Northern Ireland opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg31-7-2020 Marnix Mohrmann hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert i yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas df h kl b df h kl i ‘While we have shared past, we do not have a shared memory’ Ulster Museum Lifting the veil of the borderscape A phenomenological research on lived experience and societal processes in Northern Ireland to contribute to the critical potential of the borderscape concept A thesis by Marnix Mohrmann Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Science in Human Geography with specialization in Europe: Borders, Identity and Governance Under supervision of Dr. Olivier Kramsch Second reader: Prof. Dr. Henk van Houtum Internships: Visiting Research Associate at Queen’s University Belfast Radboud University Nijmegen, July 2020 Table of Contents List of abbreviations ......................................................................................................... i Preface -

TVLISTINGS the LEADING SOURCE for PROGRAM INFORMATION MIP APP 2013 Layout 1 9/26/14 3:17 PM Page 1

LIST_1014_COVER_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 9/26/14 2:20 PM Page 1 WWW.WORLDSCREENINGS.COM OCTOBER 2014 MIPCOM EDITION TVLISTINGS THE LEADING SOURCE FOR PROGRAM INFORMATION MIP_APP_2013_Layout 1 9/26/14 3:17 PM Page 1 World Screen App UPDATED FOR MIPCOM For iPhone and iPad DOWNLOAD IT NOW Program Listings | Stand Numbers | Event Schedule | Daily News Photo Blog | Hotel and Restaurant Directories | and more... Sponsored by Brought to you by *LIST_1014_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 9/26/14 3:25 PM Page 3 TV LISTINGS 3 3 In This Issue 41 ENTERTAINMENT 500 West Putnam Ave., 4/Fl. 3 22 Greenwich, CT 06830, U.S.A. 41 Entertainment Imira Entertainment 4K Media IMPS Tel: (1-203) 717-1120 Incendo e-mail: [email protected] 4 INK Global 9 Story Entertainment A+E Networks ITV-Inter Medya website: www.41e.tv ABC Commercial AFL Productions 23 ITV Studios Global Entertainment 4K's Yu-Gi-Oh! ZEXAL 5 Kanal D Alfred Haber Distribution Keshet International all3media international Lightning Entertainment PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS American Cinema International Yu-Gi-Oh! ARC-V: Season 1 (Animation, Animasia Studio 24 Lionsgate Entertainment Stand: R7.E59 49x30 min.) Yuya Sakaki’s dream is to become 6 m4e/Telescreen Contact: Allen Bohbot, mng. dir.; Kiersten the greatest “duel-tainer” in history–and he APT Worldwide MarVista Entertainment Armoza Formats MediaBiz Morsanutto, sales & mktg. mgr.; Francisco just might pull it off when he discovers a nev- ARTE France Urena, prod. brand assurance dir. er-before-seen technique that lets him sum- Artear 25 & MediaCorp mon many monsters at once. 7 Mediatoon Distribution Artist View Entertainment Miramax Atlantyca Entertainment Mondo TV S.p.A. -

Șișești Vatră Străbună

Asociația culturală „Renașterea Șișeșteană‖ ȘIȘEȘTI VATRĂ STRĂBUNĂ Volumul VII Asociația culturală „Renașterea Șișeșteană‖ Ediție îngrijită de Gavril Babiciu ȘIȘEȘTI VATRĂ STRĂBUNĂ Volumul VII Editura Marist Baia Mare, 2020 Descriere CIP Alte mențiuni Cuvânt către cititori! Iată-ne la al VII-lea Volum de carte, Șișești Vatră Străbună. Ideea a fost materializată întâia dată în anul 2002. Am fost consecvenți scopului urmărit, adică, în fiecare volum să scriem aspecte legate de Șișești și șișeșteni sau aspecte legate de viața și spiritualitatea șișeștenilor. Cu acest volum vom încheia un ciclu al vieții comunității noastre din primele două decenii ale secolului XXI. A fost utilă munca noastră? Credem că da. Personal, iau de multe ori de pe raft câte un volum și mă delectez citind aspecte de acum 20 de ani. Se pare că am fost de folos și altora. Din varii motive, la Biblioteca Județeană Maramureș „Petre Dulfu‖ Baia Mare a lipsit volumul II. Cartea era cerută de cititori. Neavând niciun exemplar al acestei cărți, conducerea bibliotecii a editat o serie scurtă a acestui volum, pe baza suportului electronic pe care-l aveam în bibioteca personală. De asemenea, nu puține sunt scrierile monografice sau alte lucrări și studii unde se citează din conținutul acestui serial, preluând chiar și unele imagini. Putem spune că acest mod de-a prezenta aspectele legate de viața unei comunități au inspirat și pe alți promotori ai culturii satelor în realizarea unor lucrări proprii. Acest ultim volum cuprinde trei părți. Câteva opinii și însemnări proprii. Apoi, am selectat pentru voi toți, materiale pe care, considerăm că ar trebui să le citiți, să aveți în vedere problematica supusă în atenție fiind de interes general, uneori trecută cu vederea. -

Cap.12. MUNCA EDUCATIVĂ, ACTIVITĂŢI EXTRAŞCOLARE

Cap.12. MUNCA EDUCATIVĂ, ACTIVITĂŢI EXTRAŞCOLARE. PARTENERIATE EDUCATIVE, PROIECTE LOCALE ŞI NAŢIONALE DERULATE ÎN ANUL ŞCOLAR 2018/2019 Nr.crt. Denumirea Acţiunii/ Scopul şi descrierea Locul Echipa de Data/Peri Grup ţintă Instituţiile partenere activităţilor derulate desfăşurării proiect oada activităţii/lor 1. “VORBEŞTE-MI!”- proiect Activitate desfăşurată cu Colegiul Naţional Profesorii de 26 septembrie Elevi din de parteneriat educaţional cu ocazia Zilei Internaţionale a «Mihai Eminescu» limbi străine din 2018 clasele IX- CCD MM, Colegiul Naţional limbilor europene şi având ca instituţiile XII de la «Vasile Lucaciu», Baia Mare, scop promovarea studiului partenere C.N. «Mihai Colegiul Tehnic « George limbilor germană, engleză, Eminescu » Bariţiu », Liceul Teoretic italiană, spaniolă şi franceză şi elevi din « Emil Racoviţă”, Asociaţia comunicarea în aceste limbi instituţiile Team for Youth, ARPF, MM, şi dezvoltarea creativităţii partenere Fundaţia “Centrul pentru elevilor. Dezvoltarea Intreprinderilor Mici şi Mijlocii”, Maramureş 2. « Let’s do it, Romania ! » Proiectul şi-a propus Barajul Firiza Dir.prof. Marius 15 septembrie Elevi din parteneriat cu Nature’s desfăşurarea unor activităţi CRĂCIUN 2018 clasele IX- Guardian, Baia Sprie de ecologizare în cadrul Dir.adj.prof. XII de la acţiunii Ziua de curăţenie Rodica MONE C.N. «Mihai naţională, cu scopul prof. Maria Eminescu » CIUMǍU conştientizării de către elevi a prof. Monica importanţei protejării CÂNDEA mediului înconjurător prof. Ionuţ COVACIU Prof. Anca GAVRA Prof. Gizella 1 SARKOZI 3. “Spune NU drogurilor”- Scopul proiectului a fost Colegiul Naţional Dir.prof. Marius Anul şcolar Elevi din proiect de parteneriat creşterea nivelului de «Mihai Eminescu» CRĂCIUN 2018/2019 clasele IX- educaţional cu C.P.E.C.A informare, educare şi Dir.adj.prof.