Lifting the Veil of the Borderscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Sample Newspapers and Media Coverage

Appendix 1: Sample Newspapers and Media Coverage Sample Newspapers The following newspapers are referred to throughout the monograph as the ‘sample newspapers’ that were collected over the six months data collection period (1 March 2010 to 31 August 2010). Andersonstown News Belfast Telegraph Irish News News Letter North Belfast News South Belfast News Sunday Life Sunday World, Northern Edition In selecting the newspapers, the ideological differences existing within Northern Ireland’s media have been considered and the selection is represen- tative (i.e. The Irish News aligns with the Nationalist viewpoint, whereas the Newsletter aligns with the Unionist viewpoint and the Belfast Telegraph appears not to favour or align with one specific cultural tradition or particular political ethos). © The Author(s) 2018 239 F. Gordon, Children, Young People and the Press in a Transitioning Society, Palgrave Socio-Legal Studies, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-60682-2 Table A1.1 Sample newspapers circulation figures, December 2010 Circulation Newspaper Type figure Ownership Belfast Telegraph Daily 58,491 Belfast Telegraph Newspapers Irish News Daily 44,222 Irish News Ltd News Letter Daily 23,669 Johnston Publishing (NI) Andersonstown News Twice-weekly 12,090 Belfast Media Group 6,761 (Monday) North Belfast News Weekly 4,438 Belfast Media Group South Belfast News Weekly Not available Belfast Media Group Sunday Life Weekly 54,435 Belfast Telegraph Newspapers Sunday World, Northern Weekly Not available Not available Edition Table A1.2 Other local newspapers cited The following newspapers were collected during July and August 2010 and further news items were accessed from the online archives. -

Permit to Erect and Maintain Custom Street Signs On

Permit To Erect & Maintain Custom Street & Traffic Signs On Gwinnett County Street Rights-Of-Way (Revised November 2004) The intent of this permit is to grant (hereinafter called the “maintaining authority”) the authority to erect and maintain traffic signs within the boundaries of that includes the streets named as follows: The maintaining authority is granted the permission to erect and maintain signs of the following types: Street Name Signs Stop Signs and Yield Signs Other Regulatory Signs Other Warning Signs The maintaining authority is granted this permit with the following stipulations: • No cost to Gwinnett County shall arise from the maintenance of these custom signs. • The maintaining authority agrees to indemnify Gwinnett County of any liability incurred by these signs. • In the case of residential subdivisions, the maintaining authority will be the developer and a legally constituted homeowners association mandated by the restrictive covenants. • The restrictive covenants shall contain an express provision referencing the association’s responsibility to erect and maintain signage within the subdivision in accordance with the permit. • The final plat will contain a notice signed by the developer which notifies all property owners of their responsibility for erecting and maintaining signage in the subdivision in accordance with this permit. • Installation of Street Name Signs. All street name sign blades shall be installed on top of traffic control signs (Stop, Yield, etc.) – NO EXCEPTIONS. WDJ: J & X: Custom Traffic Sign Application Form Page 1 of 8 6” Maximum clearance from top of traffic control sign to the bottom of first street name sign. 3” Maximum clearance between street name sign blades. -

1979-02-13 BCC Meeting Minutes

i ;i February 13, 1979 Page 417 In ti Ir Meeting The Board of County Commissioners met in Commission Chambers in the Courthouse 11 11 Opened 1: on Tuesday, February 13, 1979. Commissioners Allen E. Arthur, Jr.; Lamar Thomas; I ! Dick Fischer; Lee Chira and Ed Mason were present. Also present were County 1 i Administrator James Harris, Assistant County Attorney Tom Wilkes and Deputy 1 j /I Clerk Mary Jo Hudson. There being a quorum, the Chai rman cal led the meeting to I/ order at 9:00 a.m. Following the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag, the Board /I f 1 paused for a moment of silent invocation. i! it 1. Upon a motion by Commissioner Fischer, seconded by Commissioner Mason and carried, 1; I; 1 the Board approved the minutes of the meeting of January 23, 24, 25 and 1:- I i1 February 1, 1979, and waived the reading of same. I I I Warrants and Upon a motion duly made, seconded and carried, the following warrants were Vouchers approved by the Board having been certified by the Finance Director that same had not been drawn on overexpended accounts: List # Amoun t Handicapped Chi 1 d Program Head Start Program Victim Advocate Program Spouse Abuse Youth P rograms Rehabi 1 i tat ion Center Green House I I Green House Citizens Dispute Settlement Diversion Project CSA Energy Program Neighborhood Services C. D., Housing Repair CETA I CETA I I CETA I I I YETP CETA VI Child Support Enforcement Program Commun i ty Development , 4th year Commun i ty Deve 1 opmen t , 3 rd year CETA VI Pub1 ic Works Sewer Grant Solid Waste Regular Board Civic Center Fund 53 Self Insurance Fund 58 7th Gas Tax Fund 82 Attorney Upon a mot ion by Commissioner Chi ra, seconded by Commissioner Mason and carried, 1 Payment 1, the Board accepted the recommendations of staff and approved payment of $219.73 ! to Mateer, Harbert, Bechtel & Phal in for attorney costs for the month of 1 January, 1979. -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Terrorism in the Name of Religion: with Special Reference to Islam

Terrorism in the Name of Religion: With Special Reference to Islam Supervisor Researcher Dr. Fr. Tapan C. De Rozario Shah Mohammad Jonayed Associate Professor Masters of Philosophy (M.Phil.) Department of World Religions and Culture Registration No: 38 University of Dhaka Session: 2011-2012 Examination Roll Number: 2 Joining date: 17/07/2012 Department of World Religions and Culture University of Dhaka December,2018 Dhaka University Institutional Repository Terrorism in the Name of Religion: With Special Reference to Islam Thesis re-submitted to the Department of World Religions and Culture, University of Dhaka in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Masters of Philosophy (M.Phil.) in World Religions and Culture. By Shah Mohammad Jonayed M.PhilResearcher Registration No: 38 Session: 2011-2012 Examination Roll Number: 2 Supervisor Dr. Fr. Tapan C. De Rozario Associate Professor Department of World Religions and Culture University of Dhaka Department of World Religions and Culture University of Dhaka December, 2018 Dhaka University Institutional Repository Terrorism in the Name of Religion: With Special Reference to Islam Dhaka University Institutional Repository Preface All religions preach the gospel of love and it is the foundation of human existence. Without peace, justice and love nations cannot develop, and man- kind can enjoy neither happiness nor tranquility. In order to achieve social stability and world peace, there must be impartiality and harmonious living among nations, among political factions, among ethnic groups, and among religions. It is clear that peace is a divine prize that may come by the way of justice not by the terrorism. If there is religious terrorism there isn’t peace. -

Capital Improvement Plan FY 2018-19 to FY 2022-23

Capital Improvement Plan Fiscal Year 2018-2019 to Fiscal Year 2022-2023 Capital Improvement Plan FY 2018‐19 to FY 2022‐23 City Council Jonathan Ingram, Mayor Alan Long, Mayor Pro Tem Rick Gibbs, Councilmember Randon Lane, Councilmember Kelly Seyarto, Councilmember Kim Summers, City Manager Ivan Holler, Assistant City Manager Stacey Stevenson, Administrative Services Director Jeff Murphy, Development Services Director This Page Left Blank Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Capital Improvement Plan Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 Guide to Reading the CIP Project Detail ....................................................................................................... 8 FINANCIAL SUMMARY Capital Improvement Plan Sources & Uses ................................................................................................... 9 Revenue Sources ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Revenue Schedule ....................................................................................................................................... 19 Capital Improvement Projects by Funding Source ...................................................................................... 23 Unfunded Projects by Category .................................................................................................................. 35 Parameters for Budget Cost Estimates ...................................................................................................... -

Font Design for Street Name Signs

PennDOT LTAP technical INFORMATION SHEET Font DesigN for Street Name SIgns #174 The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has terminated its approval of the Clearview Highway font, summer/2016 which PennDOT had specified as the standard font for freeway guide signs and conventional highway street name signs. Standard Alphabets for Traffic Control Devices, more commonly referred to as Highway Gothic, is now the only approved font for the design of traffic signs. FHWA has not issued a mandate on the replacement of signs using the Clearview font, but all future sign installations are to use the Highway Gothic font. This means existing signs may remain in use for their normal service life but should be replaced with a sign using Highway Gothic, when appropriate, as part of routine maintenance. Highway Gothic is a modified version of the standard Gothic font and was originally developed in the late 1940s by the California Department of Transportation. The font has six configurations known as letter series (B, C, D, E, E (modified), and F). Each series increasingly widens the individual letter sizing and expands the spacing between the letters. D3-1 street name sign with Street name signs (D3-1) and most other guide signs must be Highway Gothic font. designed separately because of variability in the message or legend that limits the ability to standardize sizes. PennDOT Publication 236, Handbook of Approved Signs, provides the minimum requirements for street name signs (D3-1). Additionally, the 2009 Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) states that letters used on street name signs (D3-1) must be composed of a combination of lowercase letters with initial uppercase letters. -

Report on The6th Intercultural Practice Exchange

Navigating the journey from conflict to interculturalism: The Arts in Northern Ireland Report on the 6th Intercultural Practice Exchange 14th – 16th November 2012, Belfast, UK This event was organised by Platform for Intercultural Europe in collaboration with Arts Council of Northern Ireland This report was written by Dr Katy Radford, Institute for Conflict Research, Belfast on behalf of the Platform for Intercultural Europe www.conflictresearch.org.uk Editor: Sabine Frank, Platform for Intercultural Europe Approval: Nick Livingston, Arts Council of Northern Ireland Published January 2013 © Copyright Platform for Intercultural Europe www.intercultural-europe.org You are free to copy, distribute and cite this report under the condition that you attribute it to Platform for Intercultural Europe. Photo credits: Platform for Intercultural Europe, Arts Council of Northern Ireland, Brendan Jackson, Geoff Broadway, Rani Kasapi, Paul Kane, Oh Yeah Music Centre This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. The Platform for intercultural Europe acknowledges the This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held support of the European Cultural Foundation responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 6th Intercultural Practice Exchange, Belfast 2012– Report 2 CONTENTS P.5 OVERVIEW Background to the Platform for Intercultural Europe Arts and Interculturalism in Northern Ireland DAY ONE P.6 Welcome Reception - Address by Bob Collins, Chair, Arts Council -

Chapter 2 SIGNS

Chapter 2 SIGNS Topic No. 750-000-005 March 1999 Traffic Engineering Manual Revised: November 2017 Signs Section 2.1 USE OF SLIPPERY WHEN WET SIGNS 2.1.1 CONDITIONS FOR USE The District Traffic Operations Engineer shall request the District Maintenance Engineer to erect SLIPPERY WHEN WET (W8-5) signs at locations where it has been determined there is a slippery pavement condition. A slippery pavement is defined when a standard friction test at 40 mph has determined the skid numbers are less than 25. When the posted highway speed is above 45 mph, SLIPPERY WHEN WET signs should be installed when the skid numbers are less than 30, and also one of the following conditions is met: • When the Safety Ratio (Actual Crash Rate divided by the Critical Crash Rate) is greater than or equal to one. • Any downgrade greater than 3 percent. • At intersections with traffic signals. 2.1.2 LOCATION AND PLACEMENT Additional signs may be needed at locations with the following conditions: (1) Horizontal Curves. SLIPPERY WHEN WET signs are to be placed prior to the CURVE sign with an advisory speed plate. The ball-bank indicator provides a reasonable speed through the curve; however, a lower speed may be desired if there are known extraordinary hazards such as hydroplaning. (2) Hydroplaning. Generally, hydroplaning only occurs at speeds above 47 mph; however, excessive runoff across travel lanes may produce hydroplaning at lower speeds. Multi-lane facilities, rutted lanes, built-up shoulders, and downgrades are candidate locations. If excessive water buildup cannot be corrected, then SLIPPERY WHEN WET signs may be appropriate even when skid numbers are greater than 30. -

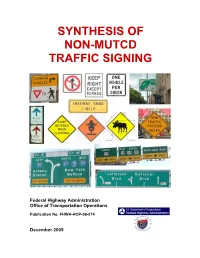

Synthesis of Non-Mutcd Traffic Signing

SYNTHESIS OF NON-MUTCD TRAFFIC SIGNING - [TURNING .. ONE VEHICLES • P VEHICLE PER j GREEN FREEWAY ENDS 1 MILE Federal Highway Administration Office of Transportation Operations .~ u,s Departrnonlo1 IrO'1SOo1ation Publication No. FHWA-HOP-06-074 If..... Federal Hlgh'l'l'OV Administration December 2005 NOTICE The contents of this report reflect the views of the author, who is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the information presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Transportation. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear herein only because they are considered essential to the document. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. SYNTHESIS OF NON-MUTCD TRAFFIC SIGNING - [TURNING .. ONE VEHICLES • P VEHICLE PER j GREEN FREEWAY ENDS 1 MILE Federal Highway Administration Office of Transportation Operations .~ u,s Departrnonlo1 IrO'1Wo1ation Publication No. FHWA-HRT-06-091 If..... Federal Hlgh'l'!,1ay AdmlnistraNon December 2005 Author The author of this report is W. Scott Wainwright, P.E., PTOE. He is a Highway Engineer with the MUTCD Team in FHWA’s Office of Transportation Operations in Washington, DC. Acknowledgements The author wishes to express appreciation to the FHWA Division Office staff in each State and to the many individuals in the State and local transportation departments. Without the assistance of these professionals, who provided the many documents, plans, drawings, and other information about special non-MUTCD signs, this synthesis would not have been possible. Special thanks are also extended to Mr. Fred Ranck of FHWA’s Resource Center in Olympia Fields, Illinois, who provided valuable review comments and suggestions that improved this report. -

Section 3 Regional Activities and Different Applications Chapter 7

“An odonym or street name is a proper name that names selected should refer to the history of the country Section 3 Regional activities and different designates a street.” or the city and its memories, to the flora and fauna in its environment. These street names should open up the applications In the same way one could define odonymy as the study world nearby or further away by referring to places or of street names, or, more general, as the study of urban Chapter 7 Street name standardisation countries with which relationships or bonds of friendship names, whether it is street names, names of buildings, exist, with whom cooperation has been established, or institutions, constructions like bridges, public parks, or Brahim Atoui with the world of science, of arts or of sports., etc. even monuments that have an important commemorative character. The attribution of names can be an act of homage or recognition for the great personalities that have marked 7.1 Introduction the history of the location, of the city or the country as Street name standardisation is just as necessary, for both 7.2 Short historical development of street naming: well as of persons with a global impact such as Nobel national and international communication, as place between popular spontaneity and political prize laureates who, by their work or by their acts, have name standardisation. interventions delivered an important contribution to the development and well-being of humanity. In place name standardisation, place names are In the past, it did not use to be the task of the processed by a recognised toponymical authority on the administrative or political authorities in a country to take That is why, in order to give concrete form to this basis of a number of rules and normative criteria that are charge of the street naming process, just as it did not approach, criteria for street name selection will be essentially aimed at guaranteeing the univocity of these take charge of toponymy either. -

Chapter 2D. Guide Signs—Conventional Roads

201109 Edition Page 151 CHAPTER 2D. GUIDE SIGNS—CONVENTIONAL ROADS Section 2D.01 Scope of Conventional Road Guide Sign Standards Standard: 01 The provisions of this Chapter shall apply to any road or street other than low-volume roads (as defined in Section 5A.01), expressways, and freeways. Section 2D.02 Application Support: 01 Guide signs are essential to direct road users along streets and highways, to inform them of intersecting routes, to direct them to cities, towns, villages, or other important destinations, to identify nearby rivers and streams, parks, forests, and historical sites, and generally to give such information as will help them along their way in the most simple, direct manner possible. 02 Chapter 2A addresses placement, location, and other general criteria for signs. Section 2D.03 Color, Retroreflection, and Illumination Support: 01 Requirements for illumination, retroreflection, and color are stated under the specific headings for individual guide signs or groups of signs. General provisions are given in Sections 2A.07, 2A.08, and 2A.10. Standard: 02 Except where otherwise provided in this Manual for individual signs or groups of signs, guide signs on streets and highways shall have a white message and border on a green background. All messages, borders, and legends shall be retroreflective and all backgrounds shall be retroreflective or illuminated. Support: 03 Color coding is sometimes used to help road users distinguish between multiple potentially confusing destinations. Examples of valuable uses of color coding include guide signs for roadways approaching or inside an airport property with multiple terminals serving multiple airlines, and community wayfinding guide signs for various traffic generator destinations within a community or area.