BSE Controversy in Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtual Conference Contents

Virtual Conference Contents 등록 및 발표장 안내 03 2020 한국물리학회 가을 학술논문발표회 및 05 임시총회 전체일정표 구두발표논문 시간표 13 포스터발표논문 시간표 129 발표자 색인 189 이번 호의 표지는 김요셉 (공동 제1저자), Yong Siah Teo (공동 제1저자), 안대건, 임동길, 조영욱, 정현석, 김윤호 회원의 최근 논문 Universal Compressive Characterization of Quantum Dynamics, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 210401 (2020) 에서 모티 브를 채택했다. 이 논문에서는 효율적이고 신뢰할 수 있는 양자 채널 진단을 위한 적응형 압축센싱 방법을 제안하고 이를 실험 으로 시연하였다. 이번 가을학술논문발표회 B11-ap 세션에서 김요셉 회원이 관련 주제에 대해서 발표할 예정(B11.02)이다. 2 등록 및 발표장 안내 (Registration & Conference Room) 1. Epitome Any KPS members can download the pdf files on the KPS homepage. (http://www.kps.or.kr) 2. Membership & Registration Fee Category Fee (KRW) Category Fee (KRW) Fellow/Regular member 130,000 Subscription 1 journal 80,000 Student member 70,000 (Fellow/Regular 2 journals 120,000 Registration Nonmember (general) 300,000 member) Nonmember 150,000 1 journal 40,000 (invited speaker or student) Subscription Fellow 100,000 (Student member) 2 journals 60,000 Membership Regular member 50,000 Student member 20,000 Enrolling fee New member 10,000 3. Virtual Conference Rooms Oral sessions Special sessions Division Poster sessions (Zoom rooms) (Zoom rooms) Particle and Field Physics 01, 02 • General Assembly: 20 Nuclear Physics 03 • KPS Fellow Meeting: 20 Condensed Matter Physics 05, 06, 07, 08 • NPSM Senior Invited Lecture: 20 Applied Physics 09, 10, 11 Virtual Poster rooms • Heavy Ion Accelerator Statistical Physics 12 (Nov. 2~Nov. 6) Complex, RAON: 19 Physics Teaching 13 • Computational science: 20 On-line Plasma Physics 14 • New accelerator: 20 Discussion(mandatory): • KPS-KOFWST Young Optics and Quantum Electonics 15 Nov. -

Running Head: FAKE NEWS AS a THREAT to the DEMOCRATIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT

Running head: FAKE NEWS AS A THREAT TO THE DEMOCRATIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT Fake News as a Threat to the Democratic Media Environment: Past Conditions of Media Regulation and Their Contemporary Applicability to New Media in the United States of America and South Korea Jae Hyun Park Duke University FAKE NEWS AS A THREAT TO THE DEMOCRATIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT 1 Abstract This study uses a comparative case study policy analysis to evaluate whether the media regulation standards that the governments of the United States of America and South Korea used in the past apply to fake news on social media and the Internet today. We first identify the shared conditions based on which the two governments intervened in the free press. Then, we examine media regulation laws regarding these conditions and review court cases in which they were utilized. In each section, we draw similarities and differences between the two governments’ courses of action. The comparative analysis will serve useful in the conclusion, where we assess the applicability of those conditions to fake news on new media platforms in each country and deliberate policy recommendations as well as policy flow between the two countries. Keywords: censorship, defamation, democracy, falsity, fairness, freedom of speech, intention, journalistic truth, news manipulation, objectivity FAKE NEWS AS A THREAT TO THE DEMOCRATIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 -

Candlelight Vigil at Chinese Embassy to Mark Save North Korea Refugees Day: September 24; Over 20 Cities Plan Action

For Immediate Release: September 21, 2015 Contact: Suzanne Scholte or Jack Rendler; Phone: 202-257-0095 (Scholte) or 612-202-8512 (Rendler) Candlelight Vigil at Chinese Embassy to Mark Save North Korea Refugees Day: September 24; Over 20 Cities Plan Action (Washington, D.C.)….On Thursday September 24, the North Korea Freedom Coalition joined by the International Coalition to Stop Crimes Against Humanity in North Korea is sponsoring the annual “Save North Korean Refugees Day" to recognize the horrifying plight and inhumane treatment of North Korean refugees by the Chinese government. Petition deliveries will occur in cities throughout the world including Washington, D.C., Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco; Seoul, Busan; Toyko; Berlin; London; The Hague; Toronto, Ottawa; Mexico City; Rio de Janeiro; Santiago; and Buenos Aires calling for the government of China to abide by its international treaty obligations and stop forcing North Koreans back to North Korea to face torture, imprisonment and even execution for fleeing their homeland. Solidarity cities including San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Waterloo, Ontario are planning events to call for action to help North Korean refugees. Several cities will also have events to mark the tragic circumstances facing North Korean refugees. For example, in Chicago, the North Korea Freedom Network will sponsor a protest at 11 am in front of the Chinese consulate, while in Washington, D.C., there will be a candlelight vigil at 8 pm at the Chinese embassy at which North Korean defectors and activists will read aloud the names of the hundreds of refugees who were forced back to North Korea by China. -

A Confucian Interpretation of South Korea's Candlelight Revolution

religions Article Candlelight for Our Country’s Right Name: A Confucian Interpretation of South Korea’s Candlelight Revolution Sungmoon Kim Department of Public Policy, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong; [email protected]; Tel.: +(852)-3442-8274 Received: 10 September 2018; Accepted: 26 October 2018; Published: 28 October 2018 Abstract: The candlelight protest that took place in South Korea from October 2016 to March 2017 was a landmark political event, not least because it ultimately led to the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye. Arguably, its more historically important meaning lies in the fact that it marks the first nation-wide political struggle since the June Uprising of 1987, where civil society won an unequivocal victory over a regime that was found to be corrupt, unjust, and undemocratic, making it the most orderly, civil, and peaceful political revolution in modern Korean history. Despite a plethora of literature investigating the cause of what is now called “the Candlelight Revolution” and its implications for Korean democracy, less attention has been paid to the cultural motivation and moral discourse that galvanized Korean civil society. This paper captures the Korean civil society which resulted in the Candlelight Revolution in terms of Confucian democratic civil society, distinct from both liberal pluralist civil society and Confucian meritocratic civil society, and argues that Confucian democratic civil society can provide a useful conceptual tool by which to not only philosophically construct a vision of civil society that is culturally relevant and politically practicable but also to critically evaluate the politics of civil society in the East Asian context. -

URL 100% (Korea)

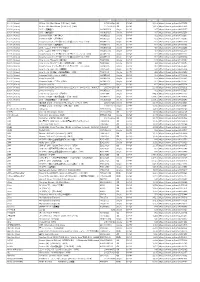

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Bab Ii “Menarikan Sang Liyan” : Feminisme Dalam Industri Musik

BAB II “MENARIKAN SANG LIYAN”i: FEMINISME DALAM INDUSTRI MUSIK “A feminist approach means taking nothing for granted because the things we take for granted are usually those that were constructed from the most powerful point of view in the culture ...” ~ Gayle Austin ~ Bab II akan menguraikan bagaimana perkembangan feminisme, khususnya dalam industri musik populer yang terepresentasikan oleh media massa. Bab ini mempertimbangkan kriteria historical situatedness untuk mencermati bagaimana feminisme merupakan sebuah realitas kultural yang terbentuk dari berbagai nilai sosial, politik, kultural, ekonomi, etnis, dan gender. Nilai-nilai tersebut dalam prosesnya menghadirkan sebuah realitas feminisme dan menjadikan realitas tersebut tak terpisahkan dengan sejarah yang telah membentuknya. Proses historis ini ikut andil dalam perjalanan feminisme from silence to performance, seperti yang diistilahkan Kroløkke dan Sørensen (2006). Perempuan berjalan dari dalam diam hingga akhirnya ia memiliki kesempatan untuk hadir dalam performa. Namun dalam perjalanan performa ini perempuan membawa serta diri “yang lain” (Liyan) yang telah melekat sejak masa lalu. Salah satu perwujudan performa sang Liyan ini adalah industri musik populer K-Pop yang diperankan oleh perempuan Timur yang secara kultural memiliki persoalan feminisme yang berbeda dengan perempuan Barat. 75 76 K-Pop merupakan perjalanan yang sangat panjang, yang mengisahkan kompleksitas perempuan dalam relasinya dengan musik dan media massa sebagai ruang performa, namun terjebak dalam ideologi kapitalisme. Feminisme diuraikan sebagai sebuah perjalanan “menarikan sang Liyan” (dancing othering), yang memperlihatkan bagaimana identitas the Other (Liyan) yang melekat dalam tubuh perempuan [Timur] ditarikan dalam beragam performa music video (MV) yang dapat dengan mudah diakses melalui situs YouTube. Tarian merupakan sebuah bentuk konsumsi musik dan praktik kultural yang membawa banyak makna tersembunyi mengenai konteks sosial (Wall, 2003:188). -

Online Activism and South Korea's Candlelight Movement

WINDOW ON ASIA Candlelight rally in Seoul, June 2008. Online Activism PC: Michael-kay Park and South Korea’s @flickr.com. Candlelight Movement Hyejin KIM The Candlelight Movement of 2016 and outh Korea has a storied history of 2017 that successfully called for President mass agitation for political causes. Park Geun-hye to step down is among the SThe Candlelight Movement of 2016– largest social movements in South Korean 17, which called for President Park Geun-hye history. This movement attracted millions to step down, is among the largest—if not the of participants over a sustained period of largest—street demonstration in that history. time, while maintaining strikingly peaceful Set against any of several measuring sticks, demonstrations that ultimately achieved their it was a remarkable success. It attracted goal. In this essay, Hyejin Kim looks at the role millions of participants over a sustained of the Internet and new media in fostering a period of time. The events were strikingly new generation of activists and laying the peaceful—strangers smashed up against each foundation for a successful social mobilisation. other and encountered police, but participants prevented violence and there was not a single fatality. And, of course, the National Assembly 224 MADE IN CHINA YEARBOOK 2018 WINDOW ON ASIA eventually impeached the President, who was in a context where such views were taboo. later dismissed, tried in criminal court, and Surveys show that individual participation eventually sentenced to a lengthy prison term. declined when these organisations entered the Globally, examples like South Korea’s are fray (Kim 2008, 30). -

ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia

2014 ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia The Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions (ANNI) Compiled and Printed by Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) Secretariat of ANNI Editorial Committee: Balasingham Skanthakumar (Editor-in-chief) Joses Kuan Heewon Chun Layout: Prachoomthong Printing Group ISBN: 978-616-7733-06-7 Copyright ©2014 This book was written for the benefit of human rights defenders and may be quoted from or copied as long as the source and authors are acknowledged. Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) 66/2 Pan Road, Silom, Bang Rak Bangkok, 10500 Thailand Tel: +66 (0)2 637 91266-7 Fax: +66 (0)2 637 9128 Email: [email protected] Web: www.forum-asia.org Table of Contents Foreword 4 Regional Overview: Do NHRIs Occupy a Safe or Precarious Space? 6 Southeast Asia Burma: All the President’s Men 12 Indonesia: Lacking Effectiveness 25 Thailand: Protecting the State or the People? 34 Timor-Leste: Law and Practice Need Further Strengthening 45 South Asia Afghanistan: Unfulfilled Promises, Undermined Commitments 76 Bangladesh: Institutional Commitment Needed 89 The Maldives: Between a Rock and a Hard Place 108 Nepal: Missing Its Members 123 Sri Lanka: Protecting Human Rights or the Government? 135 Northeast Asia Hong Kong: Watchdog Institutions with Narrow Mandates 162 Japan: Government Opposes Establishing a National Institution 173 Mongolia: Selection Process Needed Fixing 182 South Korea: Silent and Inactive 195 Taiwan: Year of Turbulence 216 India: A Big Leap Forward 222 Foreword The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA), as the Secretariat of the Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions (ANNI), humbly presents the publication of the 2014 ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia. -

SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies

School of Oriental and African Studies University of London SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies No. 38 The Rhetorical Power of Neo-Liberalism and the Strengthening of the Korean State David Hundt February 2013 http://www.soas.ac.uk/japankorea/research/soas-aks-papers/ SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies, No. 38 February 2013 The Rhetorical Power of Neo-Liberalism and the Strengthening of the Korean State NOT FOR CITATION. COMMENTS AND FEEDBACK WELCOME. David Hundt Deakin University [email protected] © 2013 http://www.soas.ac.uk/japankorea/research/soas-aks-papers/ The Rhetorical Power of Neo-Liberalism and the Strengthening of the Korean State Abstract: This article tests the assumption that neo-liberalism inevitably detracts from state strength by analysing the power of the Korean state since the Asian economic crisis. Despite expectations to the contrary, the state has retained its influential position as economic manager, thanks to a combination of two types of power: the repressive powers of the developmental state, and crucially, powers stemming from neo-liberalism itself. The Korean state used both these resources, which amount to the full spectrum of what Michael Mann refers to as infrastructural power, in its social and political struggle with civil society over economic policy. Rather than being a disempowering force, neo-liberal reform enhanced the political position of the Korean state, which presented itself as an agent capable of resolving long-standing economic problems, defending law and order, and attracting the support of democratic forces. Our findings suggest that neo-liberalism offers some states the opportunity to remain weighty economic actors, and developmental states may be particularly adept at co-opting elements of civil society into governing alliances. -

Being a “Truth-Teller” in the Unsettled Period of Korean Journalism: a Case Study of Newstapa and Its Boundary Work

Being a “Truth-Teller” in the Unsettled Period of Korean Journalism: A Case Study of Newstapa and its Boundary Work A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Wooyeol Shin IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Giovanna Dell’Orto June 2016 © Wooyeol Shin, 2016 i Acknowledgements Completing this dissertation is a long journey. Faculty, friends, family members, and Newstapa journalists have helped me along the way. I would like to express my gratitude to these people for their support. Giovanna Dell’Orto has been an inspirational adviser to me throughout my graduate years. She is not just my academic adviser but also a truly good friend. She shows me how I can strive to be a good person in the highly stressful, competitive academic field. Without GD’s support, I would never survive in Murphy Hall. I am grateful to have Seth Lewis, Sid Bedingfield, and Jeffrey Broadbent as my dissertation committee members. Seth Lewis is a productive media sociologist and an encouraging reviewer. His research program has guided me to study the sociology of journalism, especially the boundary work of journalists in the changing media environment. Sid Bedingfield provides me with thoughtful feedback on how to extend my research on journalism further. Jeffrey Broadbent has been enormously generous to me. When I found out my outside committee member, he gradly agreed with a big smile, although I had never taken his class before. From him, I learned how to think and ask questions like a sociologist. His specialty of Asian studies, as well as of social movements, also helps me develop research ideas. -

Download Solo Acting Script Rtf for Iphone

Solo acting script. Ueda Hankyu Bldg. Office Tower 8-1 Kakuda-cho Kita-ku, Osaka 530-8611, JAPAN ISO9001/ISO14001 Company Our missions please help me with a drama script of 20 mins play about how can creative industries,a vehicle for sustainable development. I'm searching for an effective script for my final project at university. I'm a drama student and I need a long monologue script for female. please help. topic– once i found a lost TEEN he lost his way. is a fantastic place to start. Smith has written several other brilliant one woman shows; another one to check out is 2016's. 6 f, 6 m, 23 either (6-38 actors possible: 3-29 f, 3-29 m). hi, need a script for reader's theater for 6 person and 3- 5mins only, well a script with emotions.. much better if its a drama. Thnks! Additional Resource: Read the ActorPoint featured article on Finding. here. Proper credit is given to authors and writers where applicable. "You're a Mad Man, Charlie Brown" Monologue-Man (12- 15 minutes). 8 f, 8 m, 14 either (16- 85 actors possible: 8-62 f, 8-54 m). Ten Great Plays for Actors in their Twenties. 5 f, 3 m, 12 either (5-18 actors possible: 5-17 f, 3-15 m). Ask your TEENdos. get the material from them and record it all. They'll relate if the words came out of their mouths. You just finesse the flow. Easier said than done, but using 'my' TEENs' ideas, words and thoughts have worked really well for me. -

14Th International Conference on the History of Science in East Asia (Paris, 6-10 July 2015): Book of Abstracts Catherine Jami, Christopher Cullen, Sica Acapo

14th International Conference on the History of Science in East Asia (Paris, 6-10 July 2015): Book of Abstracts Catherine Jami, Christopher Cullen, Sica Acapo To cite this version: Catherine Jami, Christopher Cullen, Sica Acapo. 14th International Conference on the History of Science in East Asia (Paris, 6-10 July 2015): Book of Abstracts. 2015, pp.2015-07. halshs-01220174 HAL Id: halshs-01220174 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01220174 Submitted on 25 Oct 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SOURCES, LOCALITY AND GLOBAL HISTORY: SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICINE IN EAST ASIA BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 6-10 July 2015 EHESS, Paris 14TH ICHSEA PARTNERS & SPONSORS INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF EAST ASIAN SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDECINE GDR 3398 « Histoire des mathématiques » 14TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE IN EAST ASIA SOURCES, LOCALITY AND GLOBAL HISTORY: SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICINE IN EAST ASIA BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Designed by Sica Acapo Edited by Catherine Jami & Christopher Cullen 6-10 July